Skopje is the capital city of Macedonia, of which the official name is still the “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” [FYROM]. Macedonia is one of many new democratic states in the South East of Europe, which emerged after the break-up of Yugoslavia.

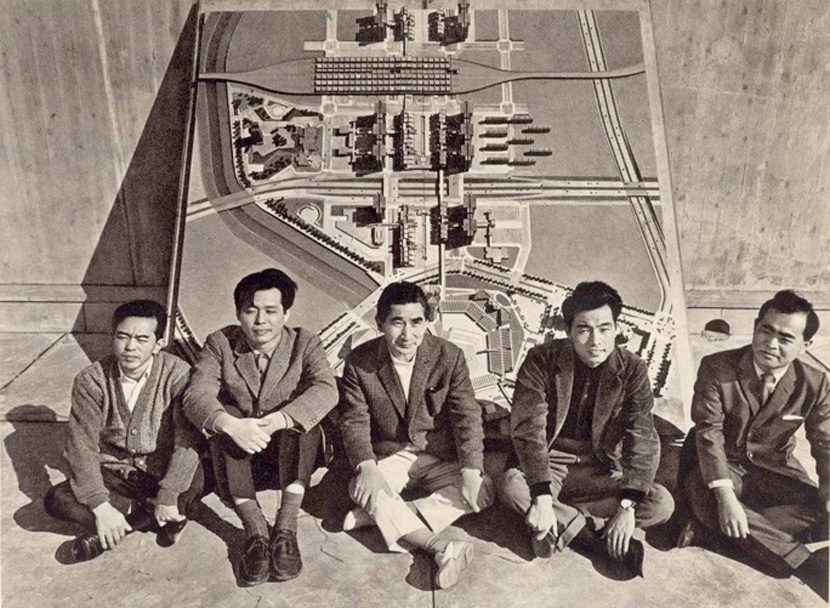

After a devastating earthquake in 1963 Skopje was rebuilt largely according to a master plan byKenzo Tange, which was supported by the United Nations and partly executed by local architects. Although it was only partially realized, some iconic modernist buildings appeared in the city, including by the Alvar Aalto-trained Macedonian architect Janko Konstantinov.

The rebuilding of Skopje was largely completed by 1980. The main elements of the Master Plan were realised on the ground, creating a new city that is today spacious and generally well-organised. The earthquake itself is a distant memory, and there are few surviving signs of it.

The Master Plan was a creature of its time. Architect-planners of the modern movement, confident in their role of remaking the postwar world, worked with the state rather than with the people. Public participation was limited to the public being allowed to view the scale model of the new city when the planners had finished it.

Today the actual Macedonian government wants to remove all traces of this plan and rewrite the Macedonian capital as a historic city with its roots in antiquity and in the period of Alexander the Great. The futuristic urbanism and architecture in Skopje is now in danger of falling victim to political attempts to fabricate an ideal past.

The debate about the future of the city is ongoing and vibrant. However, even in these debates the role of Tange’s reconstruction plan is often seen in negative terms. The main criticism is that this plan was unsuccessful in terms of its legacy. Additionally the plan is seen as a top-down experiment, that did not take into consideration forces coming from below.

Others disagree that the Japanese plan left no local legacy. To the contrary, Macedonian architects were inspired to build and contribute to their own city and to create their own voice which is now recognized as Macedonian within a larger territorial system of the Western Balkans, aspiring to join the European Union as soon as possible.