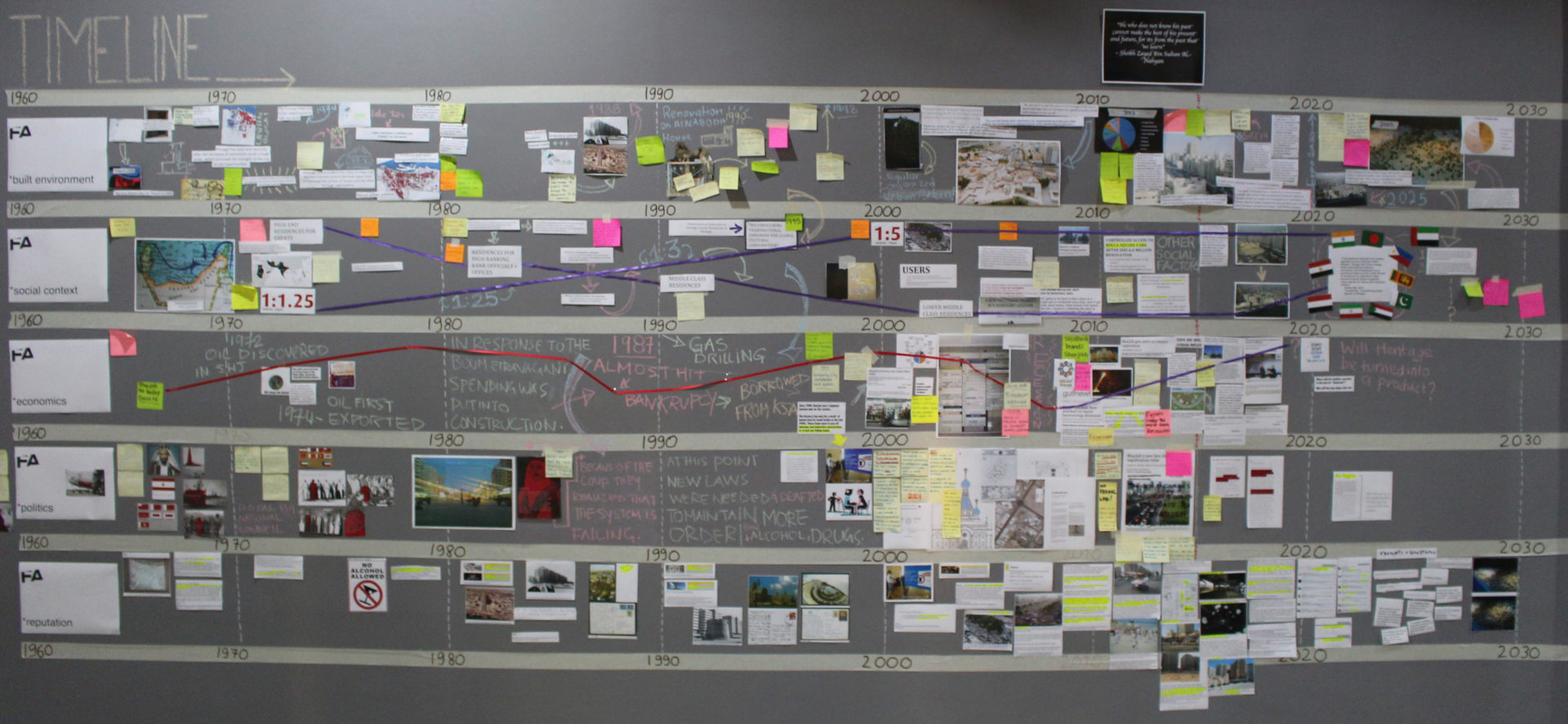

From the 23rd to the 26th of April 2014, Failed Architecture was in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, for a four day research workshop on a series of iconic buildings on the centrally located Bank Street. This workshop, the latest in the Failed Architecture series looking at a wide range of cases in various cities, has been organised in collaboration with Sharjah’s Maraya Art Centre. Participants researched the area around Bank Street, sometimes also referred to as the ‘Heart of Sharjah’, according to the Failed Architecture methodology. By conducting interviews, examining online sources, extensively exploring the area and attending a series of lectures on various related topics (full program here), the participants gathered information on the development of the area’s built environment, reputation and the social, political and economical context. The results were visualized by the participants on a physical timeline as an overview of the history, the current situation and possible futures of Bank Street’s urban fabric.

With the arrival of the oil export economy in the 70s, the cities of the UAE developed rapidly. Sharjah, just north of Dubai, was still a small fishing village at the time and embarked on an ambitious modernisation program. In the late 70s, the construction of 17 almost identical blocks in the middle of the village was initiated, consisting of apartments for the newly arrived expatriates, office space and, on every ground floor, branches of major banks. ‘Bank Street’, as the boulevard was soon to be called, replaced a major part of the historical urban fabric and soon more ‘modern’ constructions were added to the area. The buildings were designed by Spanish architects Tecnica y Proyectos (TYPSA) and were completed in 1977. The Al-Hisn fort, historically home to Sharjah’s rulers, was demolished as well, but was rebuilt in the 90s, now forming a remarkable contrast to it’s surrounding buildings. Currently, Sharjah is working on a major redevelopment of its central areas, which will include the demolition of Bank Street. It will subsequently be replaced with a low-rise, ‘historical’ quarter, in style and size similar to the reconstructed Al-Hisn fort.

On the first morning of the workshop, the participants, a mix of students and young (urban) professionals from around the UAE and the wider region visited Bank Street and the wider neighbourhood. Mr. Ammar, Project Manager at the Sharjah’s public-private development company Shurooq, guided the group around the area, explained the ambitions of the Heart of Sharjah redevelopment project and discussed its history. When asked about the fate of the buildings on Bank Street he responded without hesitation, dismissing them as ‘ugly’ and stating that they will be demolished for sure. He took the participants to a scale model of the final phase of the development plan, showing in detail how a fine grained urban fabric of ‘traditional’ structures and alleyways will replace the modernist high rise office buildings and traffic arteries. Confusingly, Heart of Sharjah does preserve some historical buildings, but the project primarily consists of reconstructing historical buildings from scratch, mostly at their original locations.

Subsequently, Sharjah Heritage Department‘s assistant director Mrs. May Al Mazrou presented the various conservation projects in the area. She explained that the Heart of Sharjah partly aims at persuading a younger generation of Emirati to move (back) into the area, an attempt to reverse the trend that started in the late 60’s when the original population was leaving the more central parts of Sharjah to build new and better homes elsewhere. The plans to historicise and pedestrianise the area were first drafted in the 1980s, but only gained momentum in recent years when the Ruler of Sharjah ordered the start of the (re-)development. The delivery of some parts of the plan have been delayed, because technical setbacks and ongoing negotiations with landlords about the terms and conditions of compensation for lost property. The plan is expected to be finished by 2025. In the meantime, the Heart of Sharjah has been tentatively listed by UNESCO as a potential World Heritage Site.

In a response to a question about the plan’s excessive emphasis on material preservation, renovation and recompilation, instead of a more social and ecological concept sustainability, Mrs. May Al Mazrou responded that these issues have been assessed and will be part of the final result. However, some participants remained wary of the social impact of the development. They wondered what will happen to the current residents, consisting largely of Indian, Iranian and other non-Emirati, who will be displaced by the demolition. And will the area still be accessible and affordable for a large audience once the high-end boutique hotels and art galleries have replaced the small barber shops and grocery stores? According to some participants, the plans and presentations didn’t give a satisfying answer.

The day ended with a presentation by George Katodrytis, architect and Associate Professor of Architecture at the American University Sharjah. He showed examples of cultural mapping and other visualisations of urban social forces and feautures. Distinguishing formal modernist grid-cities from more informal traditional Islamic urbanism, he emphasised the importance of invisible systems in the city. He argued that understanding hidden patterns, and reading cities ‘between the lines’, allows us to find new possibilities and open up space for new ideas to materialise. Talking about Madinat Jumeirah, a luxury resort in Dubai designed to mimic a traditional Arabian town, he stressed that it is a largely staged and scripted urban environment. He argued that the development of the Heart of Sharjah resembles that of Madinat Jumeirah and will ensure that tourists and other visitors will likely follow a pre-defined (and profit-oriented) path. In the narrow alleyways of the Heart of Sharjah the idea of ‘dérive’ will gain a new meaning: ‘unplanned’ wandering actually waymaking, preventing visitors from leaving the shopping district instead of a way to get lost and find space for self-expression.

The morning lecture of the second day was given by Sheikh Sultan Al Qassemi, political commentator (listed in the best 140 Twitter feeds of 2011 by TIME magazine) and founder of Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah. He reflected on and contextualised architecture in Sharjah and the rest of the UAE, specifically from the 1970s onwards. Mr. Al Qassemi started his passionate lecture by highlighting some of the more iconic pieces of modernist architecture in Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah, including the bus station of Abu Dhabi, the Blue Souq in Sharjah, and the Dubai Petrolium Company’s headquarters, which he helped save from demolition. In general, Al Qassemi noted that people are hardly thinking about preserving modernist architecture, but focus on earlier, more historical architecture. According to him, this nostalgic preservation often gives the wrong impression. It romanticises a past urban culture that does not tell the entire story. In fact, the historical urban fabric reminds many older people of poor and unsafe times and more recent urban layers appear absent from the picture.

Mr. Al Qassemi explained that the area has always been and in fact still is the beating heart of Sharjah, but that there are hardly any Emiratis living there now. Although the new plans aim to attract more into the area, he expects that Emiratis will not be very tempted to do so because their daily lives don’t take place in this area. He stated that the current population is likely to be displaced, as ‘not all of them can afford to live in glass towers’. Nevertheless, the plans which envision the Heart of Sharjah as an area of culture and history will be carried out. Al Qassemi ended by saying that “you can’t stop the locomotive of modernisation – you can at most derail it. But you’ll be seen as an enemy of progress. [..] Sometimes it is a good thing not to have money, because it preserves what’s already there.”

In the afternoon, Professor Mona El Mousfy (Professor of Architecture at the American University of Sharjah) and Sharmeen Syed (architect and researcher), who were both part of the design team of the Sharjah Art Foundation New Art Spaces and researched the central area of Sharjah, talked about it’s architectural history. Up to the mid-twentieth century, the area consisted of houses built from coral and Arish houses built from palm leaves. Bank Street was subsequently created as a part of an urban development plan by the British engineering company Halcrow. The buildings were met with mixed response, as they were perceived as a celebration of modernity for those that were able to benefit from it, but for others they were seen as a violent intervention into their habitat. El Mousfy and Syed found that over time, the area went changed, its population has gone from upper middle class to lower (middle) class, although the ethnic composition of the inhabitants remained more or less the same. They also noted that, the buildings of Bank Street are not in a deplorable state and that there are no problems with asbestos, as is occasionally said (they stripped and re-purposed one of the buildings for last year’s Sharjah Biennial). El Mousfy and Syed instead regard Bank Street and its surroundings as a “thriving and active area” with buildings of “historical and architectural value”. They are concerned by the plan to erase the 70s layer and, more importantly, the impact on its current inhabitants.

In the final two days of the workshop, the participant’s independent research intensified and the timeline in the Maraya Art Centre filled up with information. Academic articles and future plans were dissected, the area was further examined – including a viewing from the top of the buildings – and the group interviewed residents, users and shopkeepers. It became clear that the Bank Street and its surroundings is still one of the most vibrant (and walkable) urban areas of Sharjah, despite the fact that the shops are hit by economic crisis and the diminishing influx of migrants (due to stricter migration policies). It was noticed that some of the banks and property owners on the street are anticipating the demolition and are already leaving. A few of the blocks are now empty, but most tenants are unaware of the upcoming transformation. The buildings might be perceived by some as outmoded compared to what’s currently being built in both Sharjah and Dubai, they are simultaneously praised by many and clearly on the mental map of all the inhabitants of Sharjah. Also the fact one block was used for the Sharjah Art Biennale has arguably lastingly transformed the reputation of the street. Currently, there is still no federal heritage protection law in the UAE and the Heart of Sharjah will surely be pushed for by the Ruler of Sharjah. The participants observed that this will drastically reduce the total floor size of the area, and commercial and tourist areas will replace current residential space.

At the end of the final day, the timeline was finished and became a small exhibition in the Maraya Art Centre. The process of creating the timeline led to lengthy discussions with the participants, the lecturers and the FA team. It can be concluded that Bank Street is actually a functioning, lively street, consisting of iconic, sound buildings with a monumental but rare design from an important period in Sharjah’s rapid modern development. An important moment has been the 2008-2009 crisis, which forced Sharjah to reposition itself within the UAE with a new, distinguishable economic model. The chosen focus on culture, heritage and tourism led to the acceleration of the Heart of Sharjah project, which was also fuelled by the strong urge to fortify the Emirati identity of the city. This could be described as a nationalist form of ‘urban revanchism’, as Emiratis aim to clean the centre from migrant communities and reclaim it, both in architectural language as well as regarding daily usage. Given those developments, Bank Street is arguably in a rather unfortunate position, as it was built within the historic urban fabric of the city. Chances are small much of the buildings will be there in five to ten years time. Heritage from the 1970s will thus be replaced with a reconstructed imagination of what was there in the 1950s and the 1960s, making Bank Street a crucial case in the discussion on and interpretation of not only heritage but memories of the period of modern development of the Emirates, and the role of immigration in that.

The Failed Architecture workshop in Sharjah was kindly supported by the Lutfia Rabbani Foundation and the Maraya Art Centre.