Failed Architecture was invited to the Tallinn Architecture Biennale (TAB) to conduct a 5-day workshop on an iconic piece of soviet-era architectural heritage. This year’s theme of the Biennale was ‘Recycling Socialism’, which was a focus as refreshing and forward-looking as this year’s young team of curators. The exhibitions took place in several physical remnants of soviet times including the former headquarters of the communist party (currently ironically housing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and Linnahall (formerly named V.I. Lenin Palace of Culture and Sport), a colossal music/sports venue built in 1980 for the Moscow Olympics sailing regatta held in Tallinn, nowadays in an severe state of decay, largely abandoned and unused except for military training and some corners of it functioning as office space and recording studios.

Current interior view of the now largely abandoned Linnahall.

Image by Ingel Vaikla.

The full photo essay portraying the KEK-building can be found here.

The subject of our research workshop was the KEK-building in Rapla, a town just south of Tallinn. Originally built as the administrative building for a collective building organization for collective farms/kolkhozes (KEK in Estonian), the fascinating structure slowly became the victim of a political rupture and more gradual societal changes.

The building has been regarded as iconic since its construction and is still, despite currently being partly abandoned, famous amongst architecture experts as well as the general public This is also reflected in the fact that it will most likely be nominated a national monument in 2014. Notwithstanding its widespread recognition, the KEK-building is currently struggling to find new users, providing a financially viable plan for the future as well as solutions for its rapidly deteriorating physical state. Therefore, Failed Architecture was invited to break down the history of the building within its physical and societal context, with the help of around 25 participants from different backgrounds who applied to take part in the workshop. A particularly interesting aspect of this workshop was actually staying and sleeping in the building, which contributed to the experience of the building, the analyses and the group dynamics.

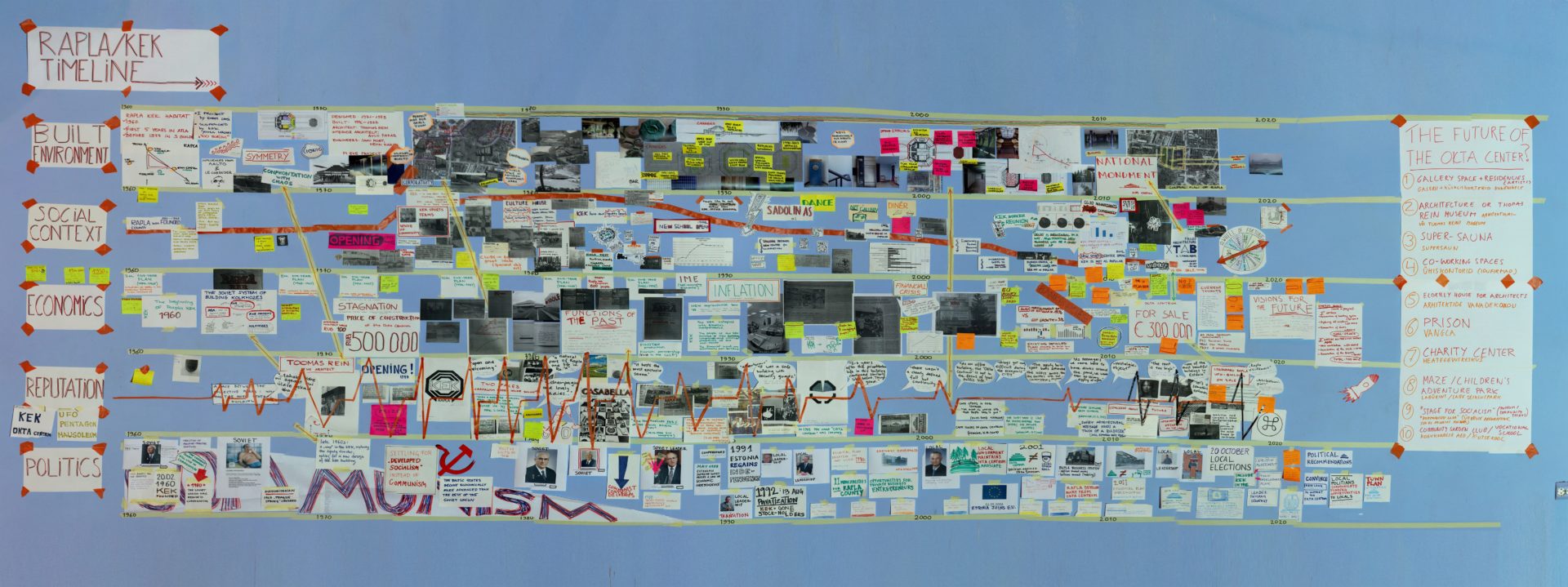

We applied our FA methodology, which has been used for many cases in different environments. We divided the participants into five subgroups, focusing on the built environment (architecture, plans, physical state, etc), the social context (demographics, use of the building, social issues, etc), economics (national and local economy, business activity in the building, financial structures, etc), reputation (media coverage, appreciation of users, locals and outsiders), or politics (political developments on several levels). The researchers were asked to find as much as information – from statistics to old photographs – for the period 1960-2020 in order to reconstruct which developments, events and decisions influenced the fate of the building and to speculate on possible future scenarios. The results were collected, filtered and organized on a timeline.

In order to focus the research and bring in extra knowledge, ten experts were invited to talk about the building, the architect, soviet times, local political, cultural and economic developments, rural development after re-independence, and local planning aspects.

The result was a 10-meter long timeline showing the life of the building within its various, interconnected contexts.

Core findings

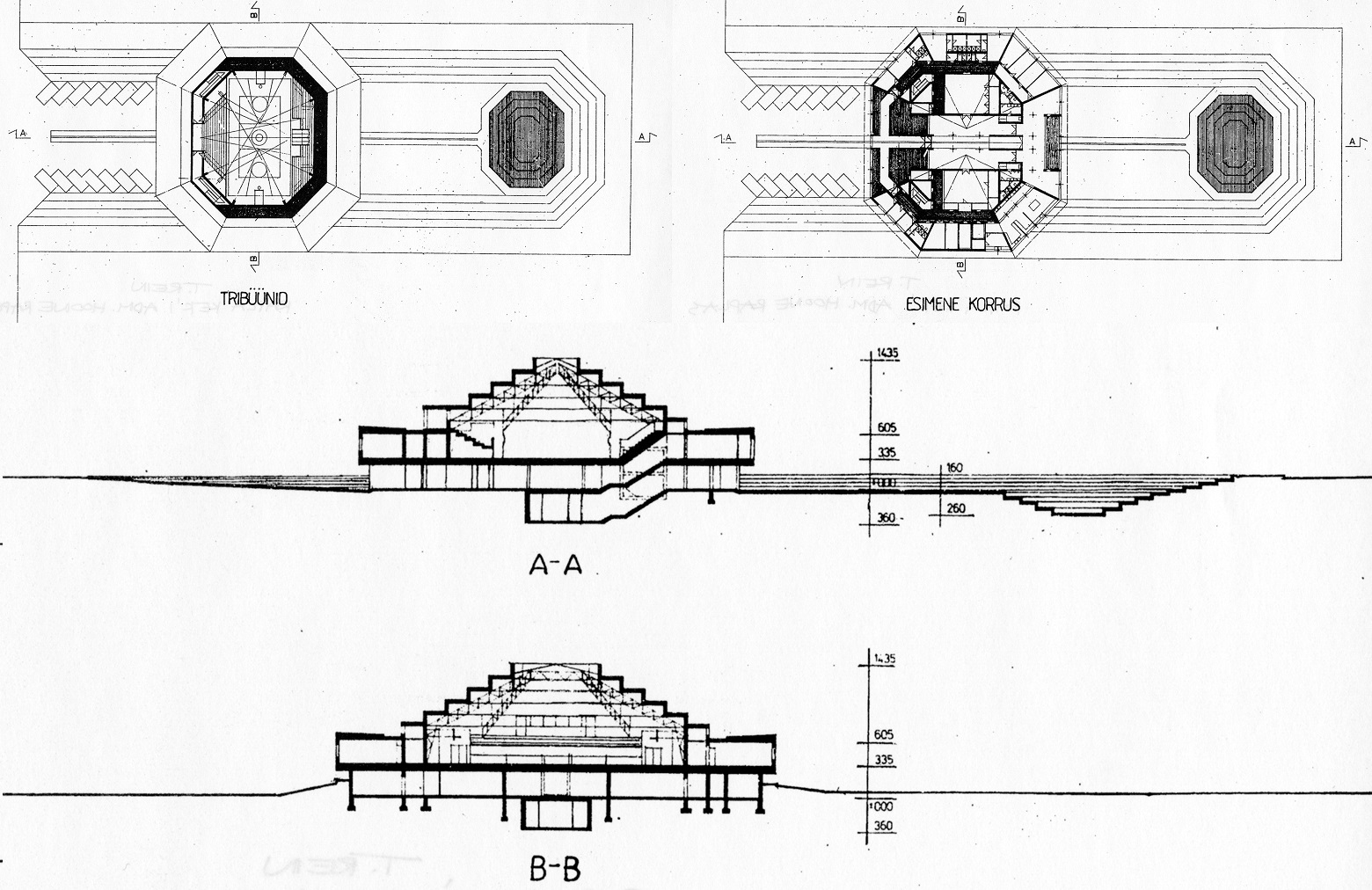

The Rapla-KEK building was finished in 1977. Its origination was a radical development, following soviet policy on collective farms. One important fact is that the KEK organization was a collective, and not a state organization. It was a central building organization of kolkhoz collective farms in contrast to sovkhoz state farms. Because of this, it was allowed – as one of the few entities – to accumulate money and invest it. There also was a race between the kolkhoz organizations in terms of prestige. This was the reason for Rapla KEK to invite architect Toomas Rein to design an iconic central building, after dismissing the previous architects because their design was “too boring”. The result was a building that acquired instant fame in Estonia and the USSR, but also in international architectural media.

The building functioned well in the years after completion. It was built for the specific use it was used for. The two-story building featured small offices (now shops), a diner and a sauna on the ground floor. The first floor housed a sports hall in the centre, with office spaces all around.

The place was teeming with activity. Next to the administrative enterprise, the building became an important social hub – not only for the around 800 people associated with KEK (who all lived close to the central building) but also for the wider public. It hosted sports events, dance competitions, discos, cinema, and other events. Those were the glorious times, the heydays of the 1980s.

The re-independence of Estonia in 1991 did not imply the immediate collapse of the building – even though it was a sheer articulation of the soviet system. When most of the state-owned organizations and collectives were privatized in 1992, KEK ceased to exist, but its subdivisions continued as separate private companies in the building. The name of the building was soon after changed into Okta Centrum.

Nevertheless, several developments and decisions sent the building into a state of semi-hibernation from the mid-90s onward. Many of the companies that emerged from the privatization went bankrupt or moved out to a new commercial complex elsewhere in Rapla. When also a new sports hall was built in the town, much of the sports activities left the Okta Centrum as well. Moreover, urbanisation trends (in terms of population and business) towards Tallinn, Tartu and other cities eroded local demands and critical mass.

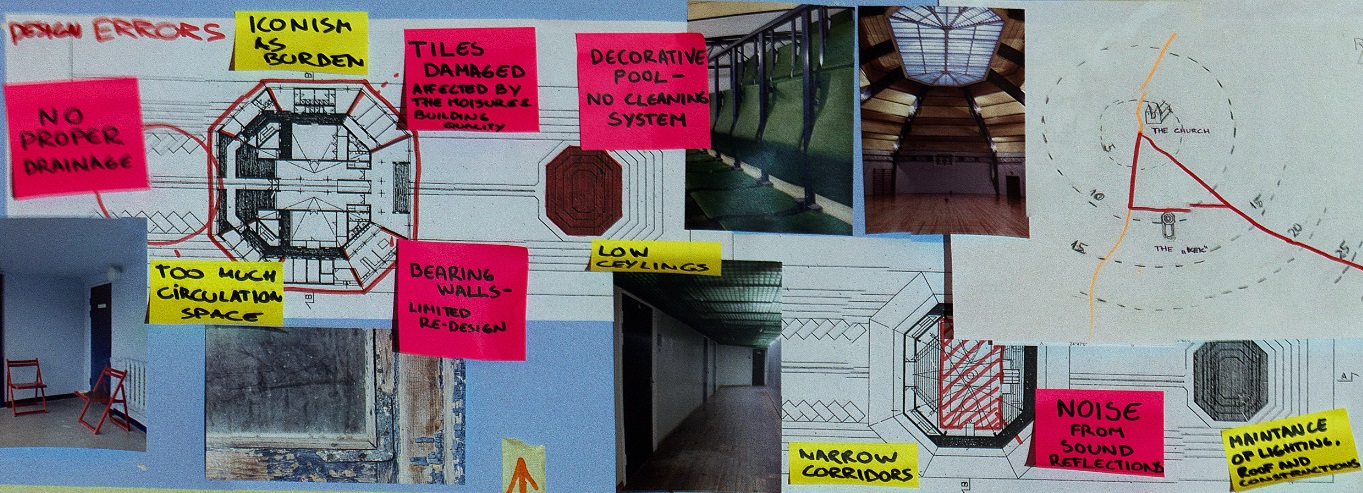

Until today, several plans were raised to revive the building, including Rapla’s town hall to move there. Nothing concrete happened, resulting in a structure that is – while being maintained as good as possible given the financial constraints – currently decaying. With almost half of the space vacant, the building is not economically viable, and because it was built for a specific set of activities leaving not much room for alterations, the conversion into another functionality is troublesome due to financial and physical limitations.

Nowadays Toomas Rein’s design only has a clear exterior identity. While interior architect Aulo Padar delivered an equally compelling interior, nowadays it is not evident what goes on inside the building, with different types of businesses tucked away in the nondescript office spaces. The ground floor now houses a charity shop, a beauty salon and a thai box school, at least drawing in some people. Next to that, some basketball is played in the sports hall. Nevertheless, the amount of people entering the building on a day can be counted on a few hands. It is apparent that something has to happen in order for the building to survive.

Urbanist Jaak Sova, part of the research team, compressed his experience of the building into a soundscape that articulates how it is underused, timeworn and often empty…

The current owners – 11 investors – are trying to sell the Okta Centrum. It is on sale for around €300,000. Required renovations would amount to around €114,000. Getting the building in great condition again would cost another €270,000. Fair amounts of money, but still reasonable for a building of such scale and symbolism. The fact that the building is likely to get a monument status in 2014 can be an advantage in terms of profile, as well as a barrier for investors to step in.

The reputation of the KEK building never hit any lows after its visionary architecture gained immediate fame when it was realised. It has always been admired by experts and locals as an extraordinary and iconic building. It only went under the radar in the last 15 years – it was there, but people didn’t know what was going on in there or what to do with it. Recently, however, the architecture received more national and international attention. Estonia’s magnificent national exhibition at the 2012 Venice Bienalle titled “How Long Is The Life of a Building?” dealt with modernist and soviet heritage, also featuring the Rapla KEK building. The same happened at this year’s “Soviet Modernism 1955-1991” exhibition at Vienna’s Architecture Centre, also showing a renewed interest in soviet modernism amongst architectural observers and the wider crowds (c.f. Frédéric Chaubin’s Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed).

Despite of the difficulties the building is currently witnessing, it still has a lot of potential. One of the week’s conclusions was that there is a need for an investor, entrepreneur or group of people with a clear idea for the building (in contrast to the current opaque ownership structure and lack of vision). Besides the quality of its distinct appearance, there are current developments which initiators could tap into. One of them being EU funds to foster non-urban developments. As Marko Gorban (Head of the Rural Affairs Department of the Estonian Ministry of Agriculture) explicated during his visit, a wide variety of activities and investments are eligible for support through these funds, up to 90 percent for non-profit initiatives. Another wave to ride could be the Finnish healthcare institutions who are increasingly looking at branching out to Estonia for their (satellite) activities. The KEK-building could be suitable for a clinic of some sort. It seems reasonable that a new function would be catering a demand that exceeds the town, given the fact that the local population isn’t growing (only ageing) and a decent income should be generated to keep the building from dying.

We also asked the workshop participants to think out loud and speculate on possible futures for the building, whether or not based on the qualities, opportunities and restrictions found during their research. Some came up with wild ideas, including a prison (given its ‘panopticon’ potential), a super sauna, an elderly home for architects and a ‘stage for socialism’ (a museum, also using the outside of the building as a grandstand and the building’s landscape as an arena). Others drew their ideas more from reality, thinking about co-working or flexible offices to reduce commuting traffic between Rapla and Tallinn, artist residencies and galleries (perhaps as a satellite location for larger cultural institutions), and vocational schools combining gastronomy and local gardening communities.