A defining property of climate breakdown is that it renders everything—humans, more-than-humans, ecologies, states, institutions, ideologies, professions—vulnerable. Nothing escapes the effects of climate and the way it induces vulnerability. All these vulnerabilities are experienced unevenly depending on demographics, privilege, and context. Vulnerability is socially produced, shaped in each instance by the specific historical and political conditions that give rise to it. Understanding the inevitability of climate impacts—both negatively and positively—becomes core to acting within climate breakdown.

In what follows, we seek to describe why architecture needs to move away from defence, despair, or the shrug of laissez-faire inevitability as responses to vulnerability, and instead move towards understanding vulnerability as a condition of empowerment: a place of individual and collective agency from which to escape the paralysis of climate anxiety and the existential dangers of climate disavowal. Vulnerability in this sense is an opportunity, one that reconnects us with interdependence, relationality, and a ‘fundamental openness to the world that implies the potential to affect others and be affected in return’. The multiple expressions of vulnerability described below are not mutually exclusive, but the experience of one might initiate action through the understanding of another. Each section of this article refers to an expression of vulnerability, which is explained using a series of architecture and spatial practices gathered from MOULD’s online project Architecture is Climate, which either confront or embody that form of vulnerability.

EXPLOITING VULNERABILITY

Vulnerability has many modes, and climate breakdown itself is a result of centuries of power structures built on the exploitation of those vulnerabilities. Colonisation operated through the subjugation of what it defined as Nonlife: people, places, animals, plants, land, and cultures that were defined as available for exploitation. Extractivist principles were employed as part of the ordering of the world, applied to both the human (as slavery) and beyond-human (in the ransacking of natural resources and their appropriation into the global flows of capital). In the anthropocentric worldview, the intentional disconnect between the human and beyond-human means that the natural world is viewed as a stockpile to be endlessly drawn on. Any sensibility, let alone concern, towards the vulnerability of these natural systems is sublimated to the higher commands of modernity. The vibrant interdependencies of beyond–human ecologies are thereby reduced to inert assets of exchange.

Under capitalism, human and environmental vulnerabilities are intertwined and manipulated for short-term gain, often with devastating social and ecological consequences. Activists such as those at Great Bear Rainforest, Dakota Access Pipeline, and other Climate Camps have been exposing ways in which the ongoing ‘smooth’ running of global north economies is reliant on a vast scale of environmental destruction. The collective cartographic work of the Environmental Justice Atlas and the Centre for Land Use Interpretation documents both sites of extraction and movements of resistance, including documenting legal struggles and calling for corporate and state accountability. Artists such as Sammy Baloji explore how colonialism continues through environmental racism, connecting social injustice and climate breakdown.

Architecture is by no means an innocent bystander to the machinations of predatory capitalism. As a profession, it turns a blind eye to its reliance on precarious and cheap labour, a dynamic highlighted by the group Who Builds Your Architecture?. As a product, architecture is used as an agent in the wider financialisation of the world. The ‘progressive’ garb that wraps buildings does not mask the underlying condition of space being primarily a measure and instrument of capital. It is because of this that organisations such as Open Systems Lab develop architectural propositions such as Fairhold by investigating the invisible infrastructures that lie beneath, rather than architecture as simply a material object.

Exploiting vulnerability is the root of climate breakdown. It is because of architecture’s complicity in the exploitation of vulnerabilities that we say Architecture is Climate. As such, in the face of climate breakdown, the apparently stable profession, people, discipline, discourses, and education of architecture become equally vulnerable.

VULNERABILITY AND RISK

The exploitation of vulnerabilities is foundational to modernity. Perhaps because of this, the standard approach modernity takes to manage its own vulnerability is one of defense. The idea of dependency—between society and environment, industry, and ecology—is intolerable; modern man has to stand astride of these contingencies. Vulnerability is inconsistent with a mindset determined by conditions of patriarchal power and control, where it is ‘figured as a shortcoming, an impending failure both of form and function’, and thus all forms of vulnerability must be overcome. Such a position sees that risks are distant, part of a febrile environment out there which can and will be tamed by the operations and instructions of us in here.

‘The human in this scenario is an expert, a problem solver, an engineer, a rational, calculating entity who is not vulnerable.’ Stacy Alaimo.

Fundamental to the idea of risk, though, is the idea of something that does not go away: the threat is not truly faced, certainly not overcome, but merely managed. Sometimes this management is enacted with the best of intentions. Liberal politics are in part specifically constituted to intervene in and alleviate the vulnerability of certain sectors of society—most obviously the poor—in the name of social justice. In the more extreme versions, the overcoming of vulnerability is posited as the premise for greater intervention and control. Such actions alleviate the symptoms but do not address the underlying conditions that have created the vulnerability—indeed, as Paolo Freire notes in Pedagogy of the Heart, such universal ‘aid-and-assistance policies [which] further immerse [oppressed people] in a mind-narrowing daily existence’ preclude them from being, and ‘assistancialize them’. Paradoxically, the shutting out of vulnerability only reinforces and perpetuates its presence. It is exactly this dynamic that is played out in the global politics of climate, most notably at the successive COP meetings, where the powerhouses of the global north offer up carbon concessions in a manner that neither challenges underlying economic and political structures nor meaningfully addresses the urgent conditions of the most vulnerable. Hierarchies of power are maintained beneath headlines of technocratic ‘solutions’.

The shutting out of vulnerability thus becomes a one-way street. Vulnerability is ascribed to certain groups, who then assume a condition of helplessness, which denies their own agency to face the situation. The person, collective, or state that defines another constituency as vulnerable does so from a position of their own presumed superiority, and with this fails to acknowledge their own vulnerability—indeed, such ‘masculine positions are effectively built through a denial of their own vulnerability [which] requires one to forget one’s own vulnerability and project, displace, and localize it elsewhere’. The vulnerable are acted upon rather than with, reinforcing paternalistic structures and logics, and the resilience of the vulnerable is celebrated in patronising asides—with insufficient critique of why those people have to be resilient or are vulnerable in the first place.

Working against such conditions and assumptions, community-based groups such as the Sweet Water Foundation in Chicago, the global Transition Network, and the solidarity networks that rapidly emerged during movements such as 15-M in Madrid seek to create space from which to build capacity rather than maintain dependency on larger systems which no longer serve them. Ideas like Distributed Design and specific examples of peer to peer networks such as Tzoumakers in Northern Greece work to wrest control back into the hands of people (such as found in product design and construction), building individual and collective agency against vulnerability rather than relying on unsustainable forms of paternalistic protection.

The overcoming of vulnerability also operates spatially, most clearly through the shutting out of risk through the establishment of boundaries: the gated community that presumes to shield the privileged from the perceived threat of the underclass; the infrastructure that protects the Netherlands from the sea, and the sea gate in Venice; the air-conditioned boxes that temporarily block out the intensity of a heat dome. In all cases, these measures exaggerate the effects of the constituting vulnerability. The shutting out of vulnerability becomes a futile gesture of performative relief.

This managerial posture dominates current climate discourse, bringing with it the language and tenets of corporate management consultants whose sole aim is to protect existing systems. Sustainability is used as a cover for perpetuating the status quo with little regard to the fact that the status quo produced the crises that society faces. Adaptation is proposed as a process of tweaking with, but not fundamentally reconfiguring, the current order. Resilience is described as a human virtue that, in some way, will enable humankind to survive. Mitigation is framed as an acceptance of breakdown, the impacts of which can be diminished but not prevailed over. These words all suggest a form of protection from the vulnerabilities of climate breakdown, suggesting that while the situation appears bad, there are tools and capabilities available to cope.

The discipline of architecture operates opportunistically within the discourse of risk. As an expert profession, it claims problem-solving as a strength, standing over and above the conditions of climate breakdown and applying isolated patches to the wounds. Under the catch-all of sustainability, architecture is particularly good at claiming its effectiveness in mitigating and adapting to the symptoms of climate breakdown, using metrics of carbon reduction as a measure of its success. Architecture thus plays an active role in the disavowal of climate breakdown via the mitigation of risk, on the one hand providing seductive images of future possibilities that distract from the very real symptoms of current ecological collapse, and on the other hand presenting itself as a form of solution.

FACING VULNERABILITY

For a profession to admit to its own vulnerability might sound like a death knell. Professions are established on the basis of authority and the execution of specialist knowledge that others do not possess. The codification and accreditation of that knowledge further sets professions apart from the rest of society. This separation leads to a form of autonomy, and with this a denial of dependency and disciplinary vulnerability. It is not surprising, therefore, that architecture treats the conditions of climate as an externality, and that its primary mode of operation in the face of this externality is through its codified systems of knowledge.

Facing its vulnerability entails architecture stepping down from its platform of isolated authority. This demands a completely reconfigured profession—one that, in its very vulnerability, joins in with the rest of the world, human and beyond-human, along with their own vulnerabilities. Professional knowledge is not abandoned (because such divestment serves no one) but is combined with the knowledge of others, professional and amateur alike. Expertise is seen everywhere: the knowledge of the everyday person is assumed to be equally valuable to that of the specialist professional. Adopting a collective approach to knowledge production, groups such as Civic Square in the UK and Aldea in Chile operate with the mantra that expertise is everywhere—that is, it is not only nice, but absolutely necessary to build climate transitions with and for everybody. The Southern Collective addresses the question of knowledge production specifically, arguing that the complexity of current challenges requires working not only collectively, but within conditions of both uncertainty and urgency, calling this way of working ‘postnormal’ knowledge production. Networks and projects such as Indigenous University and Sámi artist-architect Joar Nango’s Girjegumpi make space for other forms of knowledge. In all of these examples, the move from the protection and control of one’s own knowledge as absolute to a collective process of knowing that is dynamic, open to revision, and responsive to new inputs and perspectives is an act of truly facing the complexities of climate breakdown. The act of breaking the canon—of both design and knowledge—in terms of its formal restrictions and content emerges as a profoundly ethical and empowering stance, a conscious choice to challenge the status quo in pursuit of a more just and equitable world.

VULNERABILITY AND POWER

The reconfiguration of architecture as a discipline includes architectural education because that is where the behaviours and sensibilities are first formed, and that is where the generation most affected will find their voice. The standard pedagogical model of teachers exercising power in the classroom does not stand up to the scrutiny of students who feel the impacts of climate most keenly and who demand that education become a place for the development of collective hope and action. As bell hooks wrote of teachers growing with their students, ‘empowerment cannot happen if we refuse to be vulnerable’. The shared openness of the classroom then becomes a model for future collaboration being done in a spirit of honest receptiveness to the vulnerable position of other people, species, topographies, institutions, and so on.

This approach can be found in a number of experimental schools that have adopted critical pedagogy in their ecology and design courses. Ecological Education is based on transdisciplinary and immersive forms of community learning, exemplified by institutions such as Schumacher College, Black Mountain College, and the Indigenous University in Colombia. The Indigenous University in Colombia, in particular, adopts this approach by fostering ongoing dialogue about environmental and territorial issues, conceptualised as a form of weaving together ‘bio-cultural’ knowledges. While deeply localised in its context, the university also has a global outreach, presenting an alternative to dominant models through its profoundly ecological and social grounding.

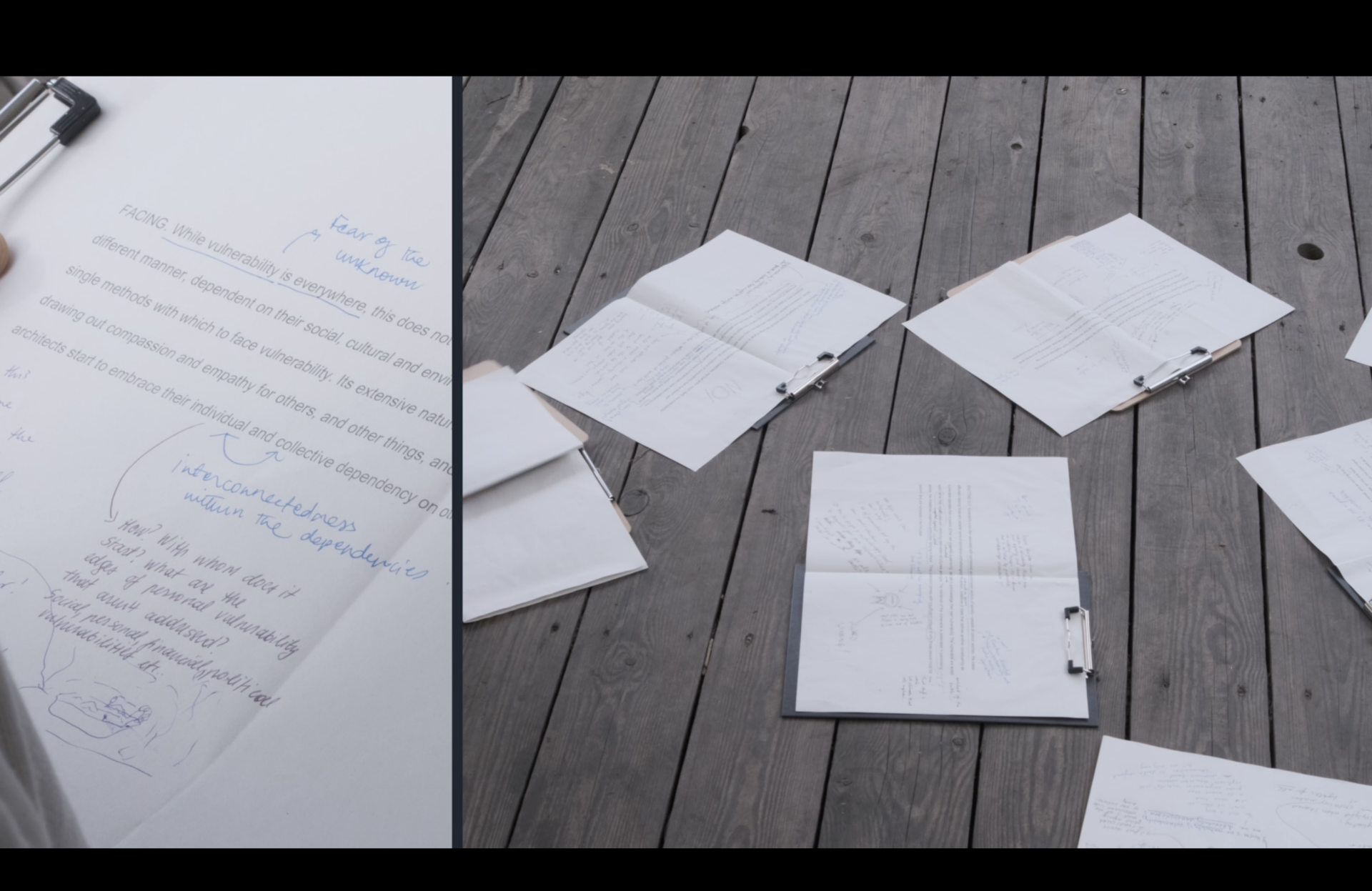

Although vulnerability is universal does not imply that it plays out in a uniform way. Everyone and everything are affected in a different manner, dependent on their social, cultural, and environmental context. This multiplicity of effects and constitution means that there are no single methods with which to face vulnerability. Its extensive nature resists the rule and order of reason, and throws us back on our humanity, drawing out compassion and empathy for others—and for the vulnerabilities of other beings and things. Vulnerability, then, also requires recognising and acknowledging the limits of one’s perspective and rejecting any notion of a singular absolute truth. An admission to one’s vulnerability deliberately embraces the partial, the situated, and the specific. It challenges the entrenched desire for definitive answers and closed-off perspectives that have long dominated fields of knowledge, including architecture.

Through all these diverse practices and many forms of collective agency such as Architects Climate Movements, Climate Assemblies, Green Belt Movement, or Wretched of the Earth, vulnerability becomes a form of resistance and so, ultimately, gathers power. Empowerment here comes as a form of resistance, as a form of action with others, as a form of building relationships and looking for allies, and as a way of creating ruptures into the dominant systems, so they can finally collapse.

This sense of empowerment as resistance differs from the standard history of architecture and power, as the agent that gives material and spatial form to dominant forces of politics and capital. Vulnerability and resistance become, on the one hand, a crucible of empathy for that of others and, on the other, a critical positioning against the forces of predatory capitalism that have created other vulnerabilities. Spatial imagination develops from within these formations rather than being imposed upon them; this grounded imagination is suggestive of new spatial formations to accompany the new social formations emerging with climate breakdown. Away from any sense of patriarchal control, vulnerability—in its very resistance—finds power in an openness to the world, one that breaks loose from the ecocidal tendencies of the carbon state. In short: vulnerability is power.