The changing climate forces a lot of uncomfortable questions. Perhaps foremost: how much is enough? On the one hand, this is being asked relative to temperature overshoots, sea level rises, heatwaves: at what point, after how many catastrophes, will enough people bear witness to this changing geophysical condition, and focus on concerted action? In spring 2022, there was some sheepish optimism when floods swept away villages in western Germany: finally, climate catastrophes hitting the centers of power, perhaps this will force a change. Again in June of last year, when Canadian forest fires produced a few days of unbreathable air in New York City: maybe this will do it! So far, it doesn’t seem to have had much impact. The waters receded, the smoke cleared. Some legislative efforts are being made, perhaps marginally amplified as these events bring to some communities what has long been impacting others. All the same, whether from the perspective of protest and activism, governance and policy, or, indeed, architecture and the building industry, there is still a sort of uncomfortable waiting, almost desperate holding on, seeing how long the chimera of business-as-usual can persist. When will it be enough?

On the other hand, this question of ‘enough’ directly renegotiates the terms of the architect’s social role as the climate has changed. From this perspective, in many parts of the world (though not all, as noted below), we have collectively built enough. There are enough highways, apartments and offices, malls and hotels, restaurants and theme parks—this despite an ongoing crisis of housing affordability. In the over-carbonised economies of the world’s wealthiest countries, maybe we don’t need to build any more, or only do so in a very targeted manner: hospitals and archives, cooling centres, housing and amenities for climate refugees. Even in these cases, there is often the capacity to reuse and redistribute what we have—to reconsider the role of design as one of maintenance, repair, and adequate comfort.

Some buildings are needed. Class A office space and luxury condominiums, not so much. After the Covid lockdowns, the vacant office space in New York City could fill twenty-six Empire State Buildings. Seems like enough. Yet there are still cranes in the sky, still new towers on the boards—indeed, the production of the built environment (and not only in New York) is essential to a growth economy. Any form of enough-ness goes against this premise of relative economic strength being measured by growth, or really by the growth of growth—how much has the GDP gone up, and at what rate? To suggest that, individually or collectively, we already have enough goes against the very foundation of consumer culture. Many life worlds are organized largely, if not exclusively, around accumulation, wanting and getting more—more stuff, more space, more savings.

The health of the US economy in particular is measured by rates of consumer spending, and through this measure implicitly directs the global supply chain. What, for example, is the carbon cost of the resurgence of interest in Barbie? The plastics, the shipping, the advertising, the repainting of houses. And given the carbon intensive energy regime that hums beneath this always-growing global economy, all of this—stuff, space, savings—is dripping in oil, vibrating with carbon intensity, keeping the arrow of emissions pointed inexorably upwards.

The Austrian/Puerto Rican economist Leopold Kohr referred to this as Skyscraper Economics—how high can we build? How much can an economy grow? Is there a measure of health, or wealth, that is not about this competitive increase, but about a horizontal redistribution? At last year’s Beyond Growth Summit in Brussels, this was framed as a distinction between “ecologically harmful growth competition and well being cooperation.” Architecture’s fealty to growth, investment, and financialization is caught up in this distinction, and faces the challenge of finding opportunities for creativity within a new set of constraints. Why, when a new building is announced on Instagram or in a glossy magazine by some proud firm or client, do we see square footage, a few swanky features, but no mention of the estimated carbon emissions of the building’s life-cycle?

Sustainable architecture has not been enough—not done enough, that is, to make a dent in this inexorable rise, not done enough to change the discipline, the profession, or familiar modus operandi. Sustainable architecture has been focused, over these last 40-odd years, on performance and efficiency: architects aim to deliver a recognizable product, albeit with a more efficient mode of operation. The typologies of sustainable architecture—from hyper-efficient curtain wall office or residential towers, to tightly sealed and conditioned bespoke luxury housing, to the complex programs and systems of institutional projects—are not categorically distinct from what we have to call “unsustainable” architecture. They are different, but not different enough.

The distinction is in performance—a sustainable building performs better, often marginally or only under optimal conditions, but still. This performative distinction, such as it is, relies on a building’s efficiency. The premise has been to build a more or less similar building, provide the same service and the same product, only with a more efficient use of energy and materials. It performs better, but otherwise it is basically the same. If you walk into a LEED Platinum building, or its cognate around the world, it might gleam and glisten a little differently, there might be more or less open space or a better air change rate, the materials might be local or more carefully produced—all important innovations, but in most cases the building itself is not so experientially different. One can do the same things—have a meeting, buy an apartment, sleep in a hotel room, in more or less the same way. The social fabric remains intact. A minor sustainable inflection to the unsustainable model of persistent economic growth.

Efficiency, that is, has not been enough. The 2022 Mitigation Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes this clear: “In most regions, the “Technical Summary” of the “Buildings” chapter of the report indicates, “Historical improvements in efficiency have been approximately matched by growth in floor area per capita.” In “developed countries,” in particular, the size of dwellings has gone up while the number of people per household has decreased. So, in the overcarbonised economies of the world, we have been building a little bit more efficiently, but we have also just been building more—still, it seems, wanting more, organizing desires and aspirations, as well as regulations, policies, and development projects, around accumulation. As Yamina Saheb, one of the writers of the IPCC report, has clarified: “The collective failure in significantly curbing emissions from buildings raises questions about whether the present approach to climate change mitigation policies is adequate and effective. Efficiency improvements, combined with the slow adoption of renewable energy and minor behavioural changes, will not deliver on the 1.5° Celsius target.”

The wanting, desiring, accumulating is perhaps at the core of a possible collective transformation—how to want something else? How to desire less—that is, to still desire, avidly, but to have the object of that desire be a reduction rather than an expansion: of space, of comfort, of luxury. How to cultivate a perspective on the world such that one can experience the fulfillment of desire in the context of a broader planetary and temporal frame—to make oneself content without relying on the suffering of others. Such is the premise of sufficiency—building a world in which the externalities are evident, and in which pleasure and aspiration takes these externalities into account.

Richard Neutra was onto this back in 1947—before, or just as, the culture of consumption was building up steam: “There has always been comfort in the world,” Neutra wrote, “reckless comfort, we could say—comfort based on someone else’s continuous labors.” Sustainable architectures have tried to operate more efficiently, but instead they have found ways for our collective desire to generate more and more externalities—the rare earth mines that produce solar panels; the waste heat that still emerges from even the most efficient air conditioner; not to mention the social and ecological costs of concrete, glass, steel and petroleum, materials specified on or necessary to operate all but the most sustainable buildings. Like a Hybrid SUV, sustainable architectures have added new externalities without attending to the old ones, offshoring toxicity and climate disruption to other communities, elsewhere.

More efficient, but also more: more floor area per capita means not only more materials and construction activity but also more space to heat and cool, usually through (increasingly efficient though nonetheless) carbon-intensive HVAC systems. This spatial growth has been simultaneous to an increase in the appliances, televisions, computers, and other equipment that both require energy themselves and also produce waste heat, further, and often dramatically, increasing cooling demands. Consumption more broadly considered plays out through the production of buildings, in finishes and details, in bookshelves and kitchen cabinets, and in the life indoors that buildings frame and condition.

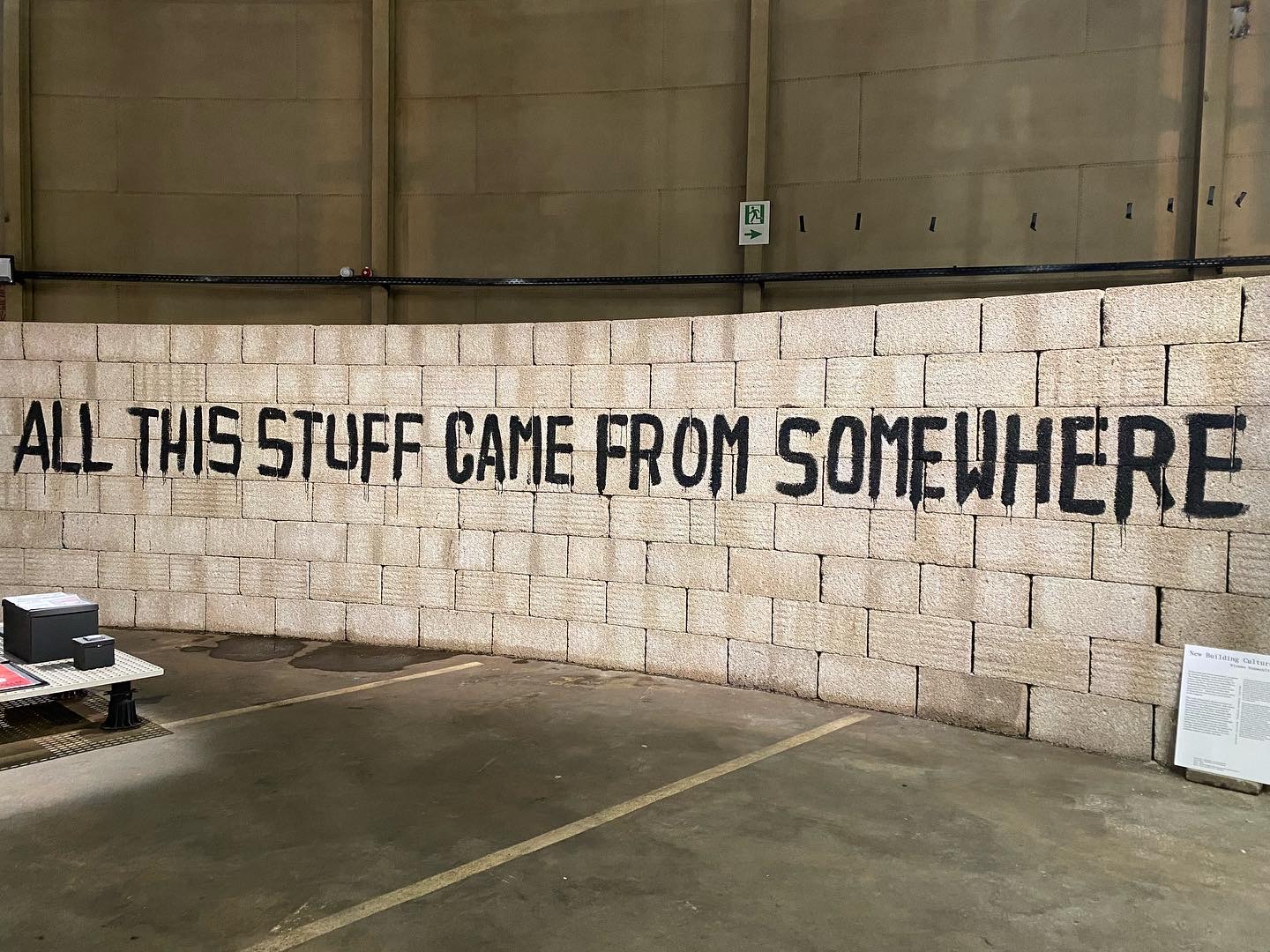

“All this stuff came from somewhere,” WERKSTATT, at It’s About Time, the 2022 International Architecture Biennial Rotterdam (and forthcoming in the related publication It’s About Time 2024). The phrase is a quote from Kiel Moe, Unless: The Seagram Building Construction Ecology (Actar, 2021).

Daniel A. Barber

The Mitigation Report, facing this conundrum and its consequences, proposes a useful, albeit discomfiting, distinction: whereas “efficiency… is about continuous short-term marginal technological improvements,” by contrast “sufficiency is about long-term actions driven by non-technological solutions, which consume less energy in absolute terms.” Sufficiency, as Saheb puts it in a related context, “is a set of policy measures and daily practices which avoid the demand for energy, material, land, water, and other natural resources, while delivering wellbeing within planetary boundaries.” Design, arguably, falls between the refinement of policy measures and the cultivation of new daily practices, renegotiating both, as it aims to reconsider its social role.

Sufficiency is about saying enough, but happily, even gleefully.

The challenge, then, is to shift the discussion of climate engagement in architecture away from efficiency, and towards thinking about how buildings can be part of a broader transformation in demand management. How can we want less—desire a world in which our needs can be met, and our aspirations realised, through a novel set of low-carbon pathways? Others have productively and provocatively framed this according to building moratoria and a renewed emphasis on embodied carbon costs. Design can focus on rendering as desirable the opportunity of living comfortably with fewer carbon emissions—through design methods themselves, and also through cultivating new modes of life, different ways of occupying buildings and spaces with an attunement to the externalities they produce. A sort of living-in-common even when not in strict spatial proximity that speaks to cohabitation—with others, with other species, with non-human agents and according to a broad understanding of the geophysical processes and dynamics in which our lifestyles participate.

This changes architecture, and its social prospects, in numerous ways: towards maintenance and repair of the built environment, away from expansion. And towards a different relationship to history—recognizing, foremost, that sustainable architecture’s main impact was to naturalize a building’s industry reliance on fossil fuels, as if other options were not viable. Historically, of course, the period of fossil fuel profligacy has been short and anomalous—there were centuries of building before fossil fuels; there are endless examples of practices and design methods by architects outside of petroleum-soaked centres of development that can support their own horizontal growth while contributing ideas on a planetary scale. Carbon path dependencies are just that—other paths are also operative, there to be expanded.

Equity also comes to the fore—sufficiency, as David Ness reminds us, requires solidarity. Given the fossil-fuel profligacy of so-called developed economies, sufficiency is, Ness explains, applicable mostly to the overcarbonised, already built economies, “where demand for new construction is questionable, while the Global South requires resources and construction to cater to burgeoning urbanisation.” Again, some buildings, some programs, some regions, require additional space and infrastructure; others do not. The distinction is between luxury emissions and survival emissions: hospitals, schools, cooling centres continue to rely on conditioning for health and wellbeing, while many houses and commercial spaces can adopt a different approach. Given that the planetary carbon budget has long been spent, and the climate has changed, where do we direct those few building practices still needed for public health and wellbeing? The sufficiency imperative is in this sense proactive: not waiting for the next catastrophe, but recognizing the catastrophic aspects present in the everydayness of growth in the built environment, and clamoring for alternatives.