Early October FA researched the past and present of Nottingham’s Lenton flats, a set of modernist high-rise tower blocks recently slated for demolition. The alleged reasons for their failure widely differ and have led to disagreements between proponents and opponents of redevelopment. During a five-day workshop, forty architecture and building technology students exhaustively discussed the causes for failure with local experts in the field of architecture, planning and housing.

Recently the British secretary of state, William Hague, accused Labour of failing to deliver for deprived urban areas, pledging that a Conservative government would make urban regeneration a top priority. Knocking down the ‘very worst examples’ of high-rise tower blocks would be a key element in the future Tory policy. But what’s new? In Britain, local governments have been knocking down tower blocks by the dozens since the late-1980s. The most recent example is the spectacular controlled explosion of one of Glasgow’s Red Road flats, which was demolished only last June. Redevelopment is also the fate that awaits the Lenton flats – although they will not get blown up but taken down floor by floor.

The flats were once the pride of Nottingham’s post-war slum clearance scheme, which was one of the largest in Europe back in the 1960s. Although they were built as affordable housing for the middle classes, they ended up as a living place for those who had no other choice. During the 1990s the estate fell into a spiral of dereliction and neglect. According to Nottingham City Homes (NCH), the company that manages the estate, the flats ‘really have to go’. It seems that a complex mix of politics, social circumstances and construction flaws has led NCH to this finale. During the workshop we scrutinized the flats’ path dependency, trying to find and comprehend the reasons for their imminent flattening.

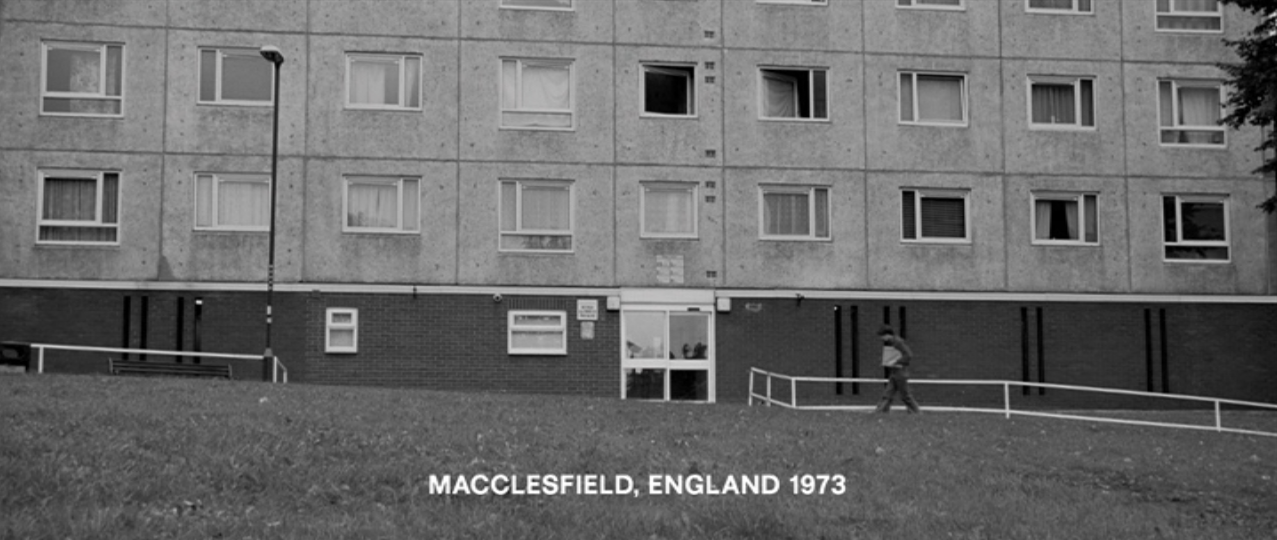

A first on-site visit and an interview with some of the inhabitants gave our workshop participants the impression that the flats ‘were not that bad’. The area’s negative reputation had clearly influenced our opinions in advance, which should come as no surprise given the role of the Lenton flats in dystopian films such as Shane Meadows’ This is England (2006) and Anton Corbijn’s Control (2007). Our opening speaker, architectural historian Ian Waites, wanted to change this ‘stereotypically grim image’ of British post-war housing estates. ‘The great adventure’ is what he called the mission on which architects, planners and administrators embarked to enhance Britain’s urban environment during the first post-war decades. Waites talked about how it was to grow up in modernist estates built during this period. By doing so, he linked an academic narrative to a more personal memory, explaining that ‘providing happiness through social housing was seen as a public task back then’. Just as the state was ‘making’ society by providing welfare services, it was ‘unmaking’ society in more recent times. During and after Thatcher’s regime, the state had increasingly been pulling back from the public domain. For Britain’s sold-off social housing stock, this led to repetitive cycles of disinvestment, residualization and a revision of policies. Nowadays, the flats are not unloved, but hard to live with, explained Waites.

While Waites blamed neoliberal policies for the failure of the Lenton flats and similar estates across Britain, our second speaker Gavin Tunstall shifted attention to construction matters. He was involved in the demolition of Nottingham’s Balloon Woods estate in the late-1980s, which features extensively in the Great British housing disaster documentary. Tunstall – trained as an architect and lecturer at NTU – stated that a lot of the estates built in the 1960s and 1970s quickly turned out to be ‘technical’ failures. Architects and planners are to blame for this, he examined, since they allegedly did not consider the quality of the built environment and the way in which people would make use of it. This problem was reinforced by the social composition of most post-war estates, where people did not share a ‘sense of place’ due to the alienating nature of the architecture and a lack of homeownership. Tunstall concluded that the principles behind social housing were praiseworthy, but that poor design and technocratic behaviour spoiled good intentions.

Fiona Corbett, manager at the Dunkirk and Lenton Partnership Forum, confirmed that the Lenton flats might lack a community feeling. Corbett’s organisation represents the interests of the current inhabitants, of which some feel increasingly lonely because of a change in the social composition over the 1990s. Initially people who wanted to move into the flats needed two references, but after tower blocks became a less desirable place to live in, the city council used them as a ‘social dumping ground’ for the elderly and rehabilitants. Some of the latter were particularly susceptible to alcoholism, drug addiction and mental health problems, which resulted in social tensions with people already living in the flats. To battle social isolation, Corbett’s organisation launched a breakfast club and other initiatives that support the residents. While Corbett dislikes the impending redevelopment scheme because of the social upheaval it will cause, she also acknowledged the practical problems. Because the flats are so badly insulated there is a lot of noise nuisance. Also, the heating costs are almost unaffordable for those living on welfare, which equals two thirds of the residents.

In between the talks and discussions, our workshop participants worked on a timeline to document the local history and to arrange the pros and cons of demolition. As the week progressed, they increasingly took up an ambivalent stance on the past, present and future of the flats. In order to clarify matters, we had invited Nottingham City Homes to explain why they initiated the redevelopment scheme in the first place. Mark Johnson, director of property services, stressed that it was really ‘the end of the line’ for the flats by giving ‘hard evidence instead of opinions’. According to Johnson, the flats had aged and were structurally unsustainable, calling them ‘our dystopian present’. They have the highest maintenance costs of the 28,200 properties NCH has to manage in Nottingham. A net present value evaluation demonstrated that the flats were just too expensive to maintain. Johnson explained how ‘this is really one of the hardest properties to manage. The flats are poorly insulated, the environment is unfit for children, the communal spaces are cramped and unwelcoming, the flats don’t work socially and many tenants are vulnerable. The question students should ask themselves is whether they would like their gran to live there.’

After summing up a list of recent technical failures such as roof leakage and uncontrollable fires in the heating system, Johnson discussed alternatives to demolition: ‘Personally, I like brutalist architecture. Recladding and refurbishing the flats is not only extremely expensive, but would also make them look rather dull and cheap.’ However, the question remained what will happen with the people living in the Lenton flats today. Johnson stressed that NCH had to make some difficult decisions, but that we should also try to look at the problem from a company perspective. Also, the decision not to invest in the flats was a political one, made a long time ago. Johnson admitted that one could speak of ‘planned neglect’ and that the current backlog in maintenance was the result of local politics, which ‘tied our hands behind our backs’.

Our last speaker was Clare San Martin, partner and architect at John Thomson and Partners (JTP). JTP is currently working on future plans for the redevelopment site, in which it wants to actively involve the existing community. By doing so, they want to generate a sense of ownership within the new developments. JTP’s analysis of the present-day situation is actually quite positive, though it also mentions the area’s flaws and problems. San Martin says that some of the stories about crime and vandalism are urban myths, while others are certainly true. There is not much monitoring and cohesion. The social composition of the area surrounding the flats is also in flux. Sixty to seventy percent of the people living in the adjacent Victorian housing developments are students – causing a significant social imbalance. In the new plans, JTP wants to tackle this problem by building more family housing on the existing site.

The site’s landscaping will get a thorough makeover. The street pattern will be changed back to how it looked prior to the 1960s redevelopment scheme: gridded and levelled, instead of winding and sloping. The new plans will only contain a fraction of the current number of council houses, which is the main grievance of people lambasting NCH’s plans. Most of the elderly will have the opportunity to move into new on-site developments, but other residents will have to go elsewhere. They will get financial compensation, but their future as social housing tenants is unsure. When asked if there had been any consideration about saving the flats, San Martin said no, since the decision to demolish them had been before JTP got involved. San Martin carefully admitted that JTP might have kept one or two flats if no restrictions were imposed.

During the final discussion participants discussed the construction quality of the flats, the fate of the inhabitants and especially the role of the architect in the dynamics leading up to the current redevelopment scheme. Our speakers continuously scapegoated politicians, even referring to ‘the system’ now and then. The site has turned into a social dumping ground, as Fiona Corbett described it, and the area is clearly in need of change. However, the workshop participants did not unanimously applaud the prospective changes. Another shared opinion was that NCH is not structurally tackling the issue because current residents will now get scattered over other less-appreciated parts of Nottingham. On the other hand, NCH and JTP were restricted by the council’s decisions. There were political and financial incentives to pull down the flats.

One student saw no other option but to engage in politics, saying ‘I’ll go to the council and shake things up!’, but others cynically concluded that local councillors didn’t have much latitude given the dismantled welfare state and a national government with a laissez faire agenda. A surprising conclusion was that according to the participants the architect was not to blame in this case; his role was hardly mentioned whilst investigating the failure of the Lenton flats. When taking into account the lessons of the workshop week, the participants said that the future should focus on sustainable, adaptable architecture with less maintenance needs. They also suggested that architects should be moderate by thinking of local consequences, and showing contractors sound alternatives whilst bearing in mind the successes and failures of the past.

More photos of the workshop week can be found here.