The Gelora Bung Karno Stadium in Central Jakarta was one of the few nation-building monuments commissioned by Indonesia’s first President and energetic leader of the independence movement, Sukarno. Built for the Fourth Asian Games in 1962 and the home of the first and only Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) in 1963, the stadium embodies Sukarno’s internationalist, anti-imperial approach entwined with Indonesia’s postcolonial nation-building project. However, less than two years after GANEFO, Indonesia’s Communist Purge had begun, leading to the former military general Suharto taking over as President in 1967. This marked a sharp line in the sand from the young nation’s socialist and explicitly anti-imperial agenda to one of crony capitalism peddled by US imperialism. As Jakarta has sprawled into a global megacity, nowadays the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium stands as a monumental relic of the values embraced by a radically optimistic, post-independence Indonesia.

This post-independence optimism is usually associated with the beginnings of the Non-Aligned Movement at the Konferensi Asia-Afrika in Bandung in 1955. In Bandung, the spirit of anti-imperial solidarity was politically formalised between the decolonising and newly independent Asian and African nations. The conference was spearheaded by President Sukarno and India’s prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, with 29 nations in total representing over half the world’s population. Hosted in Bandung’s Gedung Merdeka, a Dutch colonial building, this was a landmark moment for the world of formerly colonised people. The nations agreed to condemn colonialism in all its manifestations and laid the foundations for the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. Sukarno was keen to place Indonesia at the centre of the newly independent nations, and so used the Bandung Conference to show his nation’s ability to lead the postcolonial movement.

With a degree in civil engineering and a focus on architecture, the political and cultural symbolism of architectural form and large events was not lost on Sukarno, making him a key figure in energising the post-independence movement. Building on the Bandung Spirit, Sukarno proposed the Games of the New Emerging Forces in 1963 to be hosted in the Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex; a newly-built stadium for 100,000 people which at the time was one of the largest structures in the world. This event, dubbed the anti-imperial Olympics, would manifest the Third World project at a scale previously unseen before, with countries from across Asia, Africa, and South America increasingly united by their anti-imperial politics. By using a sporting and cultural event, Sukarno’s aim was to extend the radical vision of the Bandung Conference from the political class to the people of the Third World. If the architectural expression of the Bandung Conference was defined by the leaders of the newly independent nations re-appropriating a Dutch colonial building, GANEFO would be defined by the people of the Third World celebrating their decolonised sporting institution in Indonesia’s monumental modernist stadium.

GANEFO, however, was not necessarily a pre-meditated move by Sukarno, but in fact a direct response to a fallout with the International Olympic Committee (IOC). In August 1962, whilst preparing to host the Asian Games, the Indonesian government refused visas to athletes from Israel and the Republic of China (contemporary Taiwan), as the Indonesians believed that these nations were products of US imperialism. The IOC, led at the time by an American President, Avery Brundage, responded by barring Indonesia from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. This was the first time the IOC had done so in its history, claiming that politics should not enter the “non-political” realm of sport. The Indonesian government was furious, claiming that the IOC was functioning as an imperial tool as they themselves had already introduced the political fault lines of the Cold War into the sporting world by denying membership to Communist nations, the People’s Republic of China and North Vietnam. Within this context, Sukarno envisioned GANEFO as an anti-imperial sporting event that would directly oppose the continuing imperialism of the IOC.

Less than a week after this ruling, Sukarno announced that GANEFO would take place later that year. Sukarno laid down the gauntlet by announcing; “now let’s frankly say, sports have something to do with politics. Indonesia proposes now to mix sports with politics, and let us now establish the Games of the New Emerging Forces, the GANEFO (…) Against the Old Established Order.” By using the term “New Emerging Forces”, Sukarno explicitly created opposition against the “Old Established Forces” of the imperialist west. The Non-Aligned terminology was a neutral term to reduce tensions within the Cold War, and Sukarno had raised the stakes by challenging western post-imperial anxieties. The reception to the idea was mixed, as several nations were hesitant to take part and jeopardise their own relationship with the IOC. Whilst the IOC made threats aiming to minimise the impact and quality of GANEFO, Sukarno pushed ahead with his unapologetically provocative and politically explicit sporting celebration.

Preparations for GANEFO were drawn up at the preparatory conference in April 1963, with the games taking place in mid-November. The Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex was the ideal place to host the games as it was built for the Asian Games the year before. At the opening ceremony, 3,000 athletes represented 48 nations in front of the 100,000-person crowd. Of those nations, the largest were the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union, alongside representatives from Asia, Africa, and South America. Curiously, there were also athletes from Europe, invited by Sukarno under his loose definition of a “New Emerging Force”. Seemingly at odds with his anti-imperial agenda were the seven Dutch athletes invited to participate, yet their presence spoke to Sukarno’s vision of intertwining nationalism and internationalism. For Sukarno, the two were inseparable, as he believed that nationalism without internationalism could morph into chauvinism, whilst internationalism without nationalism could develop into cosmopolitanism.

The format of the games was broadly similar to the Olympics, with athletics alongside cycling, boxing, and swimming. However, with the slogan for the games “Onward! No Retreat!”, the political framing around the games was fully explicit. Athletes were encouraged to challenge the western ideals of pure competition and instead befriend their fellow postcolonial athletes from across the globe. The solidarity fostered between nations was valued just as much, if not more than the medals.

Alongside the sporting activities were art festivals and tours around various regions of Indonesia to help foster this sense of togetherness. Students were given a two-week holiday to work as guides during the games, and members of the public temporarily lent their cars to provide transport for the athletes, helping to build a sense of pride across the country. With a holistic set of events and small considered gestures, Sukarno was making clear that not only was this a moment of solidarity between the New Emerging Forces, but also a significant moment for Indonesian postcolonial nation-building. The impact of GANEFO’s broad-spanning vision is captured in the words of one journalist, Francisca Pattipholy, who recalled in The Jakarta Method:

“For the first time in my life, I became aware that I didn’t actually come from an uncultured or backwards people, and the other peoples of Africa and Asia weren’t backwards either (…) We played our own sports, put on our own dances. This was really an awakening for us. It felt like this was what the West had been trying so hard to keep down, for centuries, and it was finally revealed.”

Although the stadium and surrounding complex was not purpose-built for GANEFO, the design embraced Sukarno’s vision of entwining his nation-building project alongside international anti-imperial solidarity. The stadium’s official name even took after Sukarno himself—Bung Karno is an affectionate term for Sukarno, loosely translating to Brother Karno. The design and funding for the complex utilised this delicate balancing act, as Sukarno negotiated a loan of 12.5 million from the Soviet Union for the construction of the stadium, also commissioning a team of Soviet architects to lead the design process. Though an Indonesian architect might have been expected given Sukarno’s patriotic rhetoric, this partnership was strategic for both the USSR and Non-Aligned Indonesia. The Soviet Union were keen to use the stadium’s development to further leverage Indonesia’s position against the United States as part of a broader context of Soviet assistance to developing nations during the Cold War. At the same time, Sukarno utilised the Soviet Union’s significant resources to advance Indonesia’s global prominence as the nation experienced an economic crisis.

With his background in architecture, Sukarno kept a close eye on his nation-building projects, the other notable example being central Jakarta’s obelisk Monumen Nasional (Monas), to manifest his vision of contemporary Indonesia in built-form. Sukarno was less concerned with culturally specific forms of representation and instead envisioned these projects as a series of diplomatic tools. Design teams from both nations formed a close bond, consistently socialising beyond their professional work through a range of cultural events. Through this experience, the Indonesian engineers learnt new technological processes directly from the Soviet team, later playing a key role in Indonesia’s postcolonial modernising projects. In some sense, the modernist vision of the stadium was irrelevant to Sukarno. He was more interested in using the design process to build Indo-Soviet relations.

Nevertheless, modernism was clearly significant in the design of the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium. Sukarno was trained in bouwkunst by Dutch professors, and so his preference for a modernist aesthetic might superficially be read as the infiltration of neocolonial ideas. However, to him, modernism offered an almost blank canvas upon which the values of his new nation could be projected, whilst utilising contemporary construction technologies. The Gelora Bung Karno Stadium is an unapologetically homogenous use of concrete, with a porous combination of horizontal and vertical elements to suit the tropical weather. Sukarno insisted that the signature of the design was to be the cantilevered steel, circular roof, described to be a temu-gelang roof, resembling a bracelet floating above the repeated concrete elements. The robust design of the stadium was a technological solution in bringing together a young, optimistic nation. This rational approach concedes that architecture’s ability to intentionally embody national values is limited. Instead, Jakarta’s newly-built modernist stadium was simply the stage for sports to be the figure in which Indonesian national pride could grow alongside Third World solidarity.

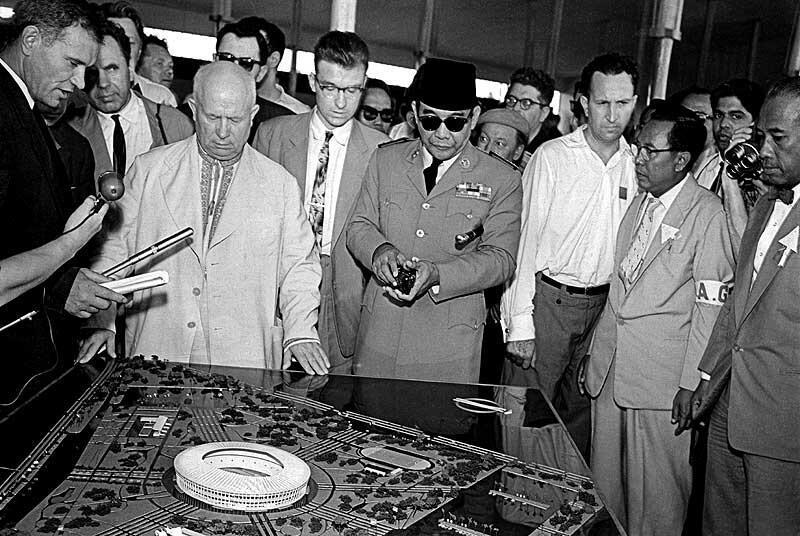

Nikita Kruschev (left) and President Sukarno (centre) Execute the Driving of the Hundredth Pile for the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium

John Dominis, LIFE Photo Collection

The stadium remains in Jakarta till today, standing as a monument to post-independence Indonesia’s radical foreign policy agenda. Just two years after GANEFO, the mass killings of Communists began in September 1965, leading to a military coup and the overthrowing of Sukarno, with Suharto taking over as President. As outlined in Vincent Bevins’ recent book, The Jakarta Method, the United States played a pivotal role in stoking anti-communist sentiment in Indonesia, as the Partai Komunis Indonesia was the largest communist party in Asia outside of China. GANEFO’s close alignment with the Soviet Union and anti-imperial rhetoric was a key indicator of Indonesia’s foreign policy at the time, causing concern in the US of losing the nation to Communism. As Bevin’s outlines, Indonesia was the testbed in which US-backed military coups would go on to transition many of the young anti-imperial nations, such as Brazil, the Republic of Congo, and Chile towards similar military-led dictatorships.

Once President, Suharto embarked upon a period of de-Sukarnoization, which included stripping Sukarno’s name from the site. This was a key symbolic move to dissociate Indonesia from its anti-imperial beginnings and its radical first President. With Sukarno no longer President, GANEFO lost much of its impetus and GANEFO II did not go ahead despite initial plans for it to be held in Cairo in 1967. With the political turnover, GANEFO was largely erased from Indonesian history with Suharto crushing plans to commemorate the event in national museums. Suharto would go on to reverse a number of Sukarno’s controversial foreign policy moves, most pertinently rejoining the IOC and competing in the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico. In just five short years, Indonesia had u-turned from hosting the anti-imperial Olympics to crawling back to the International Olympic Committee in 1968.

In the years since Suharto’s 31-year dictatorship came to an end in 1998, Sukarno’s legacy has slowly been re-integrated into Indonesian national discourse. In 2001, then-President Abdurrahman Wahid reverted the Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex to its original name, and the 2018 Asian Games brought a newfound interest in GANEFO and the founding principles of the stadium. However, the site today reflects a mix of light-touch patriotism and a shift in economic policy with corners of the site sold off to investors to help fund the maintenance of the stadium.

The eastern edge of the complex was re-developed in 1976, to build The Jakarta Hilton Hotel, one of the largest hotels in South-East Asia. Meanwhile, the south-eastern corner was redeveloped in 1996 to make way for the luxurious shopping mall Plaza Senayan. The Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex has been run by a governing body that acts as a commercial developer, exploiting the site’s commercial value to redevelop its land under the guise of maintaining its historical assets. Ironically, the development of the stadium initiated some of Jakarta’s rapid speculative growth, as it was strategically located between the colonial hub of Batavia in the north, and Kebayoran Baru in the south, creating a new centre and connecting the two. Built alongside the stadium was the Jakarta Bypass and Semanggi Junction, which was intriguingly funded by the United States, sowing the seeds for Jakarta’s expansion east and west and transforming the city into the megacity it is today. With Jakarta now becoming overstretched, and the government’s plan to relocate the capital to Kalimantan under current President Joko Widodo, it is clear that the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium is at the centre of a radically different Jakarta to the one it was built in. The complex has transformed from a site of radical anti-imperial geopolitics to an opportunistic sprawl of poorly coordinated speculative redevelopment.

In the end, GANEFO was a singular moment of postcolonial dream-making, with the Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex standing to this day as one of the few concrete manifestations of the Third World project. The stadium’s position in Indonesia’s transition from its anti-imperial beginnings to military-led crony capitalism is a similar story for much of the Third World, in which the Third World project has been stripped of its initial radical agenda to become a byword for poverty in a post-socialist world.

Whilst GANEFO was a radicalising moment aiming to empower the non-aligned nations, the reality was that it was only possible due to the loans, funding, and technical assistance from both the Soviet Union and the United States. Sukarno’s most subversive trick, and the cause of his eventual downfall, was to manipulate those resources on the international stage to suit his provocatively anti-imperial agenda. Although US imperialist intervention would not allow Sukarno’s postcolonial vision to manifest beyond this symbolic event, the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium stands to this day as a monumental reminder that the Third World is a dormant project, one that is waiting to be reignited.