Listen to this episode and subscribe to the FA podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or Overcast. More information in English below.

En medio de las protestas masivas y sin precedentes en Colombia que comenzaron el 28 de abril, el equipo de FA organizó la Situación #3 en la ciudad de Bogotá. En este primer encuentro, conversamos con Temblores, una ONG que ha liderado un llamado a la reforma policial y ha abogado fuertemente por comunidades históricamente marginadas cuyo derecho a acceder y habitar espacios públicos ha sido persistentemente negado, criminalizado y sometido a violencia policial. Junto con otras ONG, este colectivo se ha convertido en una fuente de información clave y confiable durante las protestas, reuniendo testimonios y denunciando la violencia policial generalizada durante este último mes de huelga indefinida.

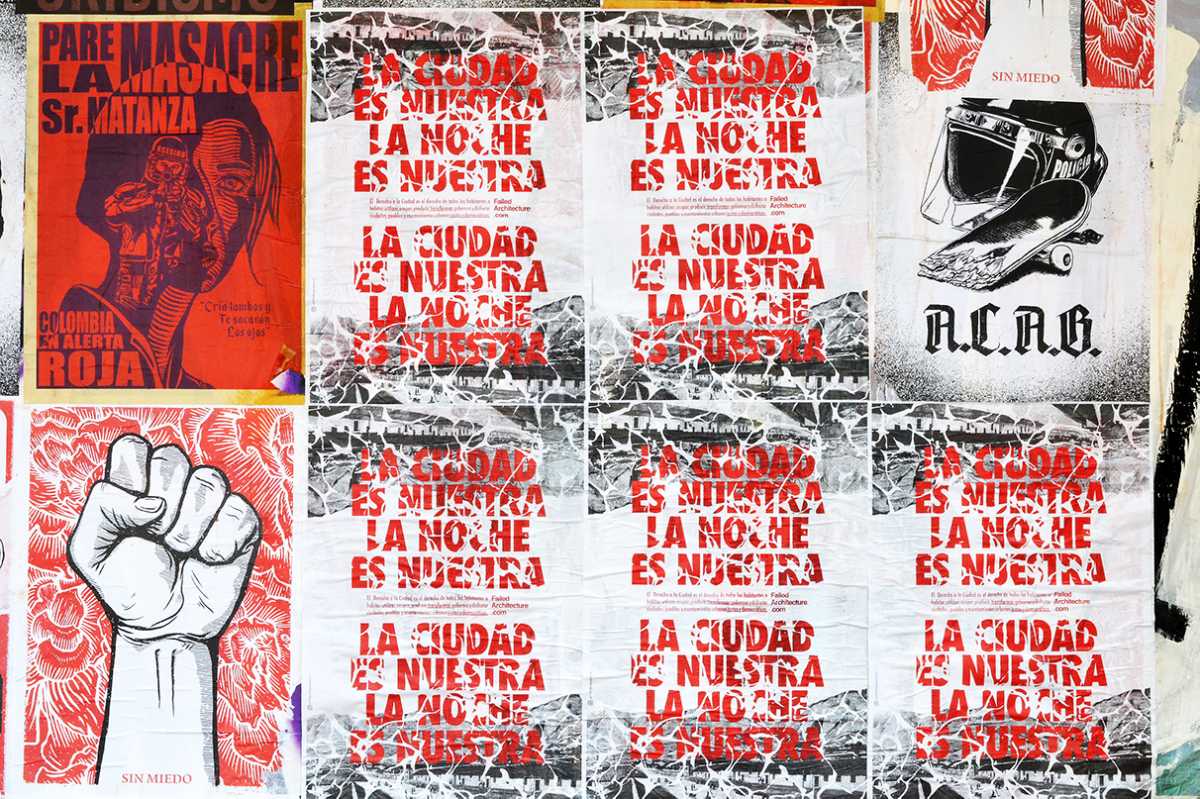

La situación #3 incluyó una acción pública colectiva en las calles de Bogotá. El equipo de FA produjo una serie de carteles diseñados por la editora Maria Mazzanti y los instaló en varios espacios públicos de Bogotá. A raíz de las protestas, este medio ha florecido como una forma de expresar las voces de los manifestantes, dejando evidencia de este movimiento social en las ciudades. Con la ayuda del impresor Adolfo Ayala, dueño de Carteles Bogotá, el equipo de FA utilizó este medio para subrayar nuestro derecho constitucional a protestar pacíficamente y a habitar, transformar y producir la ciudad día y noche. Este es un gesto modesto para cuestionar el discurso oficial que, obstinadamente, sigue estigmatizando a los manifestantes como vándalos y terroristas.

– Alejandro Rodríguez, ONG Temblores

– Nicolás Fernández, estudiante de arquitectura

– Camilo Andrés Méndez, estudiante de arquitectura

– Carolina Alvarez, Iniciativa Bloomberg para la Seguridad Vial

– FA Bogotá (Laura Buitrago, María Mazzanti, Juana Salcedo, Juan Sebastian Sepúlveda)

Este episodio fue dirigido por Maria Mazzanti/the Failed Architecture team.

English Information (Text: Juana Salcedo)

The notion that public space is for everyone, a place where we are all equal, has been used ambivalently to legitimize the exclusion of marginalized and vulnerable populations and to defend their presence in these spaces. Authorities and other social groups, uncomfortable with the presence of the homeless, loitering teenagers, street vendors, sex workers, and protesters, among other ‘undesirables,’ tend to justify their expulsion from public space by appealing to the “public good” or the prevention of “social harm.” The use of public space as a strategy for either “social justice” or “social order” led geographer Bernd Belina to question the pervasive use of this idealized notion of public space and its abstract promise of equality as a vehicle for social change. Instead, he argued, it might be more important to ask “why the ‘reserve army of labour’ as a socioeconomic reality and its feared visible presence in urban spaces as a moral problem exist in the first place.” For him, such a stance would direct the conversation towards how our current economic model often entails the punishment of the poor and move us from the idealism of public space towards identifying concrete demands and struggles of specific marginalized populations.

This is precisely what the Colombian NGO Temblores, which translates to quakes, has been doing in Colombia since 2016. Founded by siblings Alejandro and Sebastián Lanz, Temblores works in the realm of what they refer to as Strategic Community Litigation. Through this approach, they have worked with homeless, trans communities, and protesters, identifying their concrete struggles and making a case to change the structures that maintain the exclusion, violence, and discrimination and the systematic negation of their rights. In the work of this NGO, equality is not an abstract aspiration that carries within a normativized way of being. On the contrary, their work refers to very concrete lives at stake whose right to access and inhabit public spaces have been persistently denied, criminalized, and subjected to police violence.

For example, Temblores proved that the lack of free public restrooms in Colombian cities and the prohibition of public urination and defecation in the Police Code affected citizens and particularly harmed habitantes de calle, peoples whose private lives take place in the public realm. (Rather than homeless, in Spanish, this term refers to people who inhabit the streets). The code led to extreme violence by police officers. At least twelve habitantes were murdered while urinating or defecating. Temblores has also actively worked with trans communities in Bogota, finding that, despite new inclusive public policies, trans people continue to be targeted by the police and others when entering public spaces and that these assaults tend to be dismissed by authorities who blame the victims as inciting the violence due to their own physical appearance. Furthermore, the collective showed that the right to protest publicly, particularly by peasants, indigenous communities, and students, has been curtailed and violently repressed through the militarization of protest with the Escuadron Móviles Antidisturbios Esmad (Mobile Anti-riot Squad), whose presence at demonstrations has become pervasive, leading to police abuse and the outright violation of human rights.

Temblores’ work is not academic research but rather a series of substantial cases made in collaboration with affected populations. They produce evidence to litigate in the justice system, tools for policymakers and authorities, and accessible documents to be shared and discussed with the wider public. The collective has had some wins. The Constitutional Court forbade public authorities from indicting habitantes de calle and demanded cities provide free public restrooms; the latter of which remains to be enforced by city authorities.

In all of these cases, the struggle for public space involves the police, the main actor in charge of overseeing and managing public conduct in Colombia and, therefore, the first institution that requires a structural transformation. Temblores has elevated to Congress a strong case against systematic police violence. In 2019, as part of their call for “Reforma Policial Ya,” (Police Reform Now) Temblores launched Grita! (Yell!), a collective platform that invites citizens to register and denounce police violence and offers legal counselling for those affected.

In the midst of the unprecedented and massive protests that spread across both cities and rural areas on April 28th, the Failed Architecture team organized Situation #3 in Bogota to talk to Temblores. Temblores, along with other NGOs, has become a key and reliable source of information at this time, gathering testimonies and reporting the widespread police violence. According to their latest report, the protests have led to 45 murders, many or all of which can be traced back to police forces, 346 disappeared persons, as well as at least 3,692 cases of police violence, including 25 victims of sexual violence, 1,445 arbitrary detentions and 62 victims of eye aggression with rubber pellets.

While the initial cause of the protests was a government tax reform, its roots can be traced at least as far back as the earlier wave of protests in 2019. Then, the grievances centred on the failed social, economic, and environmental policies of the elected right-wing government, its reluctance to implement the peace agreements with the FARC (Latin America’s oldest guerrilla), and the systematic murders of social leaders throughout the country. These grievances have since only intensified, with the economic devastation brought by the COVID pandemic in a country that already was one of the most unequal in the world. Now, protesters have successfully derailed the tax bill and declared an indefinite strike. While mainly pacific and rich in cultural demonstrations and initiatives from young people, peasants, and indigenous communities, among other groups, there have also been violent clashes, some involving armed (paramilitary) civilians siding with the police.

FA Bogota talked to anthropologist Alejandro Rodríguez, coordinator of Temblores’ platform Grita!. The conversation also included Camilo Andrés Méndez and Nicolas Fernández, who are part of a collective of architecture and design students who have joined the protests in Bogota, as well as Carolina Álvarez, a civil engineer working in the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety. The dialogue revolved around Temblores’ research and litigation processes in their quest to defend the right to the city. Among the main topics discussed was the potential of collective work; the negation of public spaces caused by the mix of social distance measures imposed by authorities to face the pandemic; the recent decentralization of protests across neighbourhoods and “resistance posts;” as well as the police violence taking place mostly at nights, along with targeted electricity cuts and internet blockages. This latter situation led Temblores to make the hard choice of recommending protesters to leave the streets and take shelter by night. While this curtails the right to the city, for the NGO, this call is intended to preserve a fundamental right (the right to live) from the deadly aggression of government forces.

Alongside the dialogue, Situation # 3 included a collective public action in the streets of Bogota. The FA team produced a series of posters designed by editor Maria Mazzanti and installed them across various public spaces in Bogota. The almost extinct art of wheat pasting as a medium of communication has declined in this digital era. Public authorities have restricted it only to designated areas in a bid to prevent ‘visual pollution.’ In the wake of protests, this medium has flourished as a way to express the voices of protesters, leaving evidence of this social movement across cities. Editors Juan Sebastián Sepúlveda and Laura Buitagro went out to the streets to share the posters with protesters and sent some to Espacio Odeón’s proposal to build a memory of the strike in a collective wall. With the help of printer Adolfo Ayala, owner of Carteles Bogota, the FA team used this medium to underscore our constitutional right to protest peacefully and the right to inhabit, transform and produce the city during day and night.