This article is part of the FA special series The Climate Changed.

If climate changed, so must our pedagogies and practices. Within architectural education in the UK, most institutions have adopted the ‘Unit System’ as its core mode of delivery: a Unit ‘master’ sets the agenda of the design studio about his/hers/their own research agendas. This system has proved to elevate single voices, raise competition, and focus on the reproduction of the Unit ‘master’s’ canon. How can we think about positive climate action when driven by individual action, reproducing a master narrative, and in competition with others?

Weaving vessels for a liminal dialogue is the title of a Collaborative Unit part of the MA courses in Architecture at Central Saint Martins (University of the Arts London) that offers students the chance to explore their entangled relationships with land, nature, and belonging. It foregrounds climate emergence rather than emergency, critiques the nature/culture binary, and anchors embodiment and belonging as spatial and architectural design methodologies.

Co-designed by Ana Maria Gutierrez from Organizmo —Training and Research Centre for Regenerative and Intercultural Knowledge (Colombia)— and Catalina Mejia Moreno, Climate Lead at Spatial Practices CSM, in conversation with Andreas Lang, M-Arch Course Leader, and Judith van de Boom course leader of the MA program in Regenerative Design, Weaving Vessels promotes cooperation over competition. As part of a wider pedagogical driving force of the M-Arch, Weaving Vessels takes the students’ lived experience as an entry point to a deep inquiry into spatial practices and nurtures interdisciplinary thinking within the university’s postgraduate community. Weaving Vessels is also, importantly, the only module within the M-Arch accredited course that is written out of the RIBA – the Royal Institute of British Architects (accreditation body). It therefore opens a space for new ways of working and collaborating, new inquiries, and freedom in terms of content and delivery such as working through open, collaborative processes that are not primarily outcome-driven.

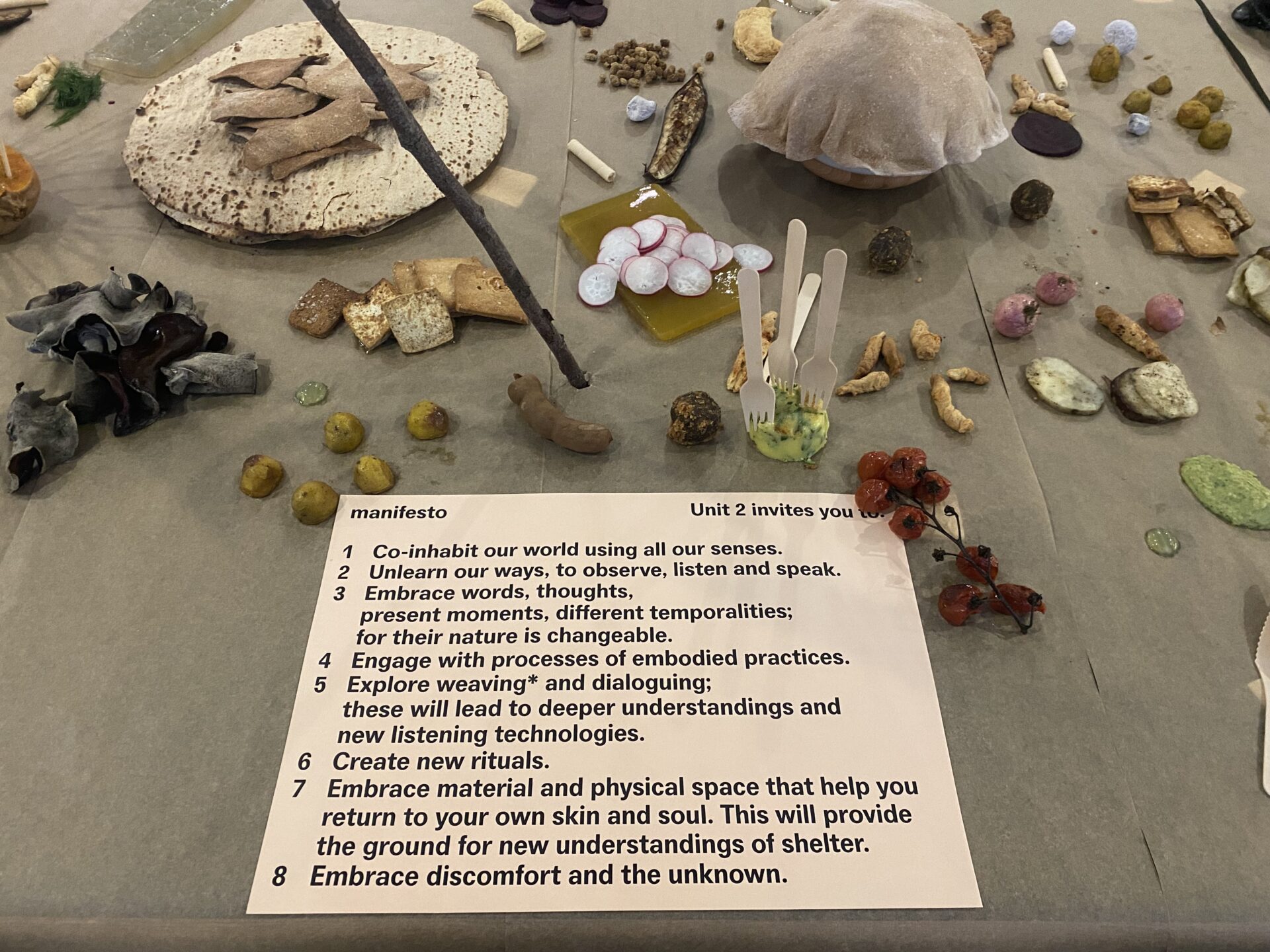

Our invitation to all students and staff read:

Co-inhabit our world using all our senses | unlearn our ways to observe, listen and speak | embrace words, thoughts, present moments and different temporalities for their nature is changeable | engage with embodied practices and processes | explore dialoguing and weaving; these will lead to deeper understandings and new listening technologies | create new rituals | welcome understandings of new shelter through material and physical spaces that return you to your own skin and soul | embrace discomfort and the unknown | weave vessels for liminal dialogues.

Architecture students in the UK (and probably more widely) work predominantly in urbanised contexts where the concern with inter-human social relations, and man-made systems dominates over a deeper relationship to nature, land, and our ancestral belonging. The Collaborative Unit allowed us to open a pedagogical space that shifted away from this inter-human focus. It also opened space to question some of the prominent Anglo-Saxon technocratic, symptomatic and carbon centred ‘fixes’ responses that fail to engage with the multiple entanglements of the intersecting crises (amongst many others, social, spatial, environmental, and importantly epistemological). In response, Weaving Vessels foregrounds relationality as design methodology – thinking through relations and connectedness rather than isolation -, inviting students to embrace embodiment – embrace lived experiences as they are made manifest in one’s body – and other ways of knowing, and to think about their creative processes through multispecies kinship: with each other, the land, and the forest. As such the design work is less solution focused but instead emphasizes how we can establish, nurture and design modes of relating that are nuanced, complex and caring.

Bringing voices usually overlooked within the UK architectural education realm to this conversation was crucial. We invited Ana Maria Gutierrez to co-create with us. For many years Ana has been committed to working with different ethnic and indigenous communities across Colombia and beyond, centering intercultural dialogues and knowledge exchange through spatial and material processes. In Organizmo, Ana has further explored regenerative practices which, as a response to the challenges posed to all living ecosystems, center dialogue, cooperation, co-creation and acknowledgement of each other, non-human and more than human entities.

For Weaving Vessels we also invited Pedro Jajoy, a long-term friend from the Inga Indigenous Peoples of Colombia with whom we share stories, histories, and projects, to co-create with us land-based practices rooted in ancestral practices. We hosted the Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña, the Colombian artist Barbara Santos, and the Colombian master bamboo builder Jaime Peña, amongst others. Together, these voices reinforced the possibility of climate action through architectures that are attentive to others, to land, and to working otherwise. They foregrounded the importance of living practices based on rituals, traditions, and ancestral belongings that, even if interrupted by the broken worldviews that prioritise development and profit and colonial continuities, remain to carve out practices and imaginations for possible futures.

As part of the co-creation process that defines Weaving Vessels, our invitation to students was to embrace a loose learning path that invited students to weave their living architectural practice and their embodied knowledge into a forest. In this case the ancestral woodland of Highgate Woods in London originally part of the Ancient Forest of Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Essex. According to the City of London Corporation, the plant and animal species found here today have evolved naturally since the last ice age and have been managed to varying degrees by humans through the ages. In small groups, we also asked the students to co-create a spatial or material vessel in response to this act of weaving. Drawing from Ana’s experience, this invitation focused on building up students’ intuition and knowledge through embodied experiences as they relate to a forest, and their potential resignification through dialogue with one another. It was a learning path that was open, and in constant flux informed by the student’s engagement, questions, and emotional responses.

To begin this journey, we invited students to reflect on their relations with natural environments, ancestral lands and practices, and the emotions and reactions that these prompted. Ana invited students to dig a hole in the ground as a means of foregrounding the multiple relations between soil, tactility, and memories, but also material and matter. Pedro asked students to place their hands on the understory of the forest, and to dig down with their hands until they could feel the wet winter soil with their fingers. For many it was the first time, for many it didn’t make sense, and many didn’t do it. We invited students to spend one day a week in the forest for seven weeks, establishing a dialogue with it, and designing their own learning paths and group vessels in response to it. Collaboratively, we drew a map of the UK, to locate known and familiar rituals and ceremonies that entailed a relationship between our bodies and land. We heard from spring harvest rituals to rituals that came to the UK via Ghana, Vietnam, Ireland, and others and that still take place within family homes, gardens, and community spaces. All of these prompted emotional responses or connections that later became the drivers of the students’ spatial or material vessels.

After seven weeks, the group vessels materialised as rituals, ceremonies and objects that created temporal and ephemeral spaces in Highgate Woods. Some Vessels were built shelters designed with foraged and industrial wood – as one that resembled the protective and nurturing feeling of inhabiting hollow core of a tree. Some were defined by paper and fabric and forest-based materials fabricated by the students – as the blanket that the whole group touched and drew, and later lifted to embrace a dead tree. Some were spatial rituals – as brooming, rhythmically, the leaves of the understory of the forest with a Ghanaian praye (broom). And some was an invitation to contemplate the students’ ritual of resignification of the forest – as dance of cast fabrics raised to the wind.

Without exception, all vessels moved emotional and emotive responses – something until then absent or suppressed within our teaching spaces. These were characterised, in most cases, by discomfort: ‘these seven weeks’ invitation was a personal struggle. The spatialization of rituals of belonging, and of our relationship to the forest [is] undoubtedly the hardest design project I have worked on. We were working on a domain I have not been exposed to before. There was no clear and defined issue such as the housing crisis. I felt lost and frustrated, hesitant and doubtful. [Scarlett].’ ‘Discomfort was constructive. The outcome (performative or built) is not the one you get from traditional ways of thinking architecture [Bertie].’

But also, in other cases by an intimate feeling of returning home: ‘This unit made some of us connect with questions of spirituality, to reconnect with ancestral roots which we never thought we would within an architecture course [Lauren].’ Or by a willingness to engage with the openness that our invitation entailed: ‘Throughout the course of the seven weeks, we sat with emotional processes that stemmed from the invitation to engage with non-pragmatic approaches to architecture and validated them as design processes. We went through discomfort, and we slowed down. We created space to think through softness, temporality and ephemerality, to think about climate and ecology; to think how to act today in a world that is characterised by its many crises [Holly].’ Or by a realisation: ‘One thing that stayed with me is the time given to value things, and to realise not everything has to be evaluated in the same way. Things can have a social and spiritual value. Design processes and decisions do not always have to come from something based on climate science. For instance, carbon. In some cases, better if it doesn’t [Tom].’ Or by a reflection: ‘Our seven-week design immersion was an invitation to think differently on how to connect and relate oneself with the surrounding environment – whether natural or others. It was an opportunity to dig deep, position yourself and your spatial practice, and use that position to collaborate with others [Alice].’

In the words of Shin Egashira, architect and tutor at the Architectural Association who joined us in the forest this last day, student’s rituals, as opposed to performances, passed on to us observers, essential values through small acts. Students critiqued western notions of nature and culture, and engaged with nature in ways they wouldn’t probably have imagined. For Gilly Karjevsky, Berlin-based curator who was also with us, students reflected on their living practice and their connection to ancestralism as embodied practices. For us, students disrupted processes and explored sensibilities through simple gestures. They foregrounded belonging, they brought to the fore a new language that is soft, committed, personal, propositional, and different from the one we are used to within academic institutions in the UK context.

Borrowing the words of researcher and publisher Alice Grandoit-Šutka, Weaving Vessels became a ‘pocket of possibility’ within the student’s architectural studies that allowed for a recognition of co-inhabitation and co-existence, of embracing kinship, and of thinking about futures – ‘capsules that propel us forward’ – rooted in ancestral pasts, as Ailton Krenak, environmental philosopher and leader of the Krenak peoples of Brazil, has repeatedly called for. Even through naivety or in some cases poetry, students recognised the potential of working through emotions and belonging as a form of living relational practice that shapes their relational ecologies. A practice that we hope that, as geographer Katherine Yusoff calls for, challenges the very idea of the Anthropocene. What students did, in the end, was to recognise ‘the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions. It emphasizes critical connections, authentic relationships, listening with the body and the mind;’ what the writer Adrienne Maree Brown refers to as ‘emergence.’

In the current ills of the world, that have shaken us to the core (that dramatically continue to unfold as we finalise this piece), we wholeheartedly believe and trust as this being the way forward.

We are feeling in the dark to an understanding of light

embodied experience of our own history,

generational and ancient

Touch brings us into our bodies and the knowledge they know beyond our explicit awareness.

How do we create a new tactile epistemology?

To the tree, it is all connected and affected, its path to the present is visually expressed.

Its roots hidden, reach out in infinitely complex ways.

We too are affected, we leave impressions, both experiential and physical,

yet they sit latent from us.

How do we bring these impressions to the fore of our conscious reality?

Extract from Scarlett, Ran, Twearly, Amy, and Nelha’s manifesto.