In May, 301 miners were killed in the town of Soma in Western Turkey. According to Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the disaster was just another “ordinary work accident”. This “business as usual” attitude has met with claims that the disaster was in fact wholly preventable, claims which rest on conflicting views of the role of architecture.

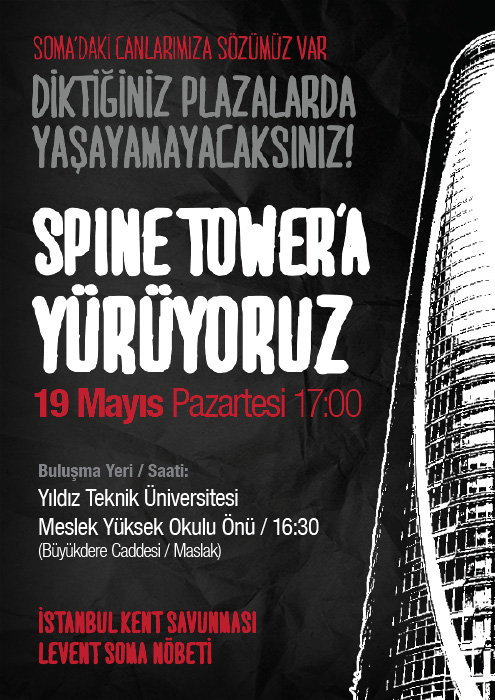

The architecture in question concerns two specific sites: the mine itself and the Istanbul skyscraper Spine Tower. The mine lacked the 20 rescue chambers which, at a cost of $250,000 each, would have helped prevent nearly all of the 301 mortalities. The skyscraper, recently built in Istanbul’s financial district Maslak by the same company that operates the mine, is home to 80 super luxury flats each priced at $1,350,000. The comparison is self-evident: the cost of saving the miners would have been less than the price of 4 flats in Spine Tower.¹

That mega-projects such as skyscrapers are often undertaken at the expense of human life is by no means a revelation (as the 1990s heavy metal band Acid Bath sang, “skyscrapers look like gravestones”). However, the question of where architects ought to stand within that relationship indicates a relatively underexplored topic of discussion. This recently became all the more evident when Zaha Hadid was asked about the construction workers’ deaths in Qatar (currently numbering around 1000) where a series of projects are being undertaken in preparation for the 2022 World Cup, including the starchitect’s Al-Wakrah stadium. Hadid’s reply was that “it’s not my duty as an architect to look at it; I cannot do anything about it because I have no power to do anything about it.”

Many have discussed such controversies as a question of moral responsibility. I would like to explore the idea that in the case of large-scale projects—architecture as (big) business—the profession’s link with social and material destruction has become so inextricable as to require an altogether new definition of what falls within its professional domain—in not just ethical but also practical terms.

First, a bit of history is in order. After all, the close relationship between violent losses of human life and architectural mega-projects such as skyscrapers goes back many years. Consider William A. Starrett, the contractor who was involved with the construction of many of America’s best-known skyscrapers including the Empire State building. Having started his professional career as a colonel in the US army, Starrett was responsible for all construction activity that the army undertook during World War I. About a decade after starting his civilian life, the contractor would expose the close link between the two consecutive halves of his professional career that may otherwise seem unrelated. “Building skyscrapers is the nearest peace-time equivalent of war,” Starrett suggested in 1928:

“. . . the analogy is startling, even to the occasional grim reality of a building accident where maimed bodies, and even death, remind us that we are fighting a war of construction against the forces of nature.”

In other words, according to Starrlett and others like him, architectural projects driven by mega-investment and the latest building technology are sacred causes. In contrast, human life is inferior, its loss is expected.² This was indeed the implication that characterized the way in which government authorities in Turkey negotiated the disaster in Soma. “This is in the nature of this business,” argued Prime Minister Erdoğan. He called the victims “martyrs,” a term coded in the popular psyche in Turkey as a status granted to soldiers who die in combat.

But the kind of relationship that links architecture to situations of large-scale social and material destruction such as war is much more than just metaphorical. As architect and cultural theorist Eyal Weizman has influentially demonstrated, over the past couple of decades warfare has increasingly become an urban affair. It implicates architecture as not a mere backdrop but very much the medium of combat and witness in the legal processes that follow those of armed conflict. Similarly, Andrew Herscher has shown that architectural destruction during and after war is far from “collateral damage” or “senseless vandalism,” and is rather itself a specific form of cultural production through the built environment. If war has come to resemble an architectural project, might the reverse also be true? Indeed, Turkey’s recently launched series of state-sponsored “urban renewal” projects predicated on “the Law on Disaster Prevention” are often spoken of as having turned Istanbul into a warzone. The resemblance is so evident that Fikirtepe, a neighborhood where the socially and materially destructive impact of “renewal” is fiercest, has begun to host crews filming scenes set in the war-ridden Syria (something which has led the neighbourhood to be dubbed “Fikirwood”). This “renewal” is architecture in its purest, that is, ostensibly most technical and least ideological form, practiced not in a context of war or its aftermath but in the name of preventing disaster in an urban setting. And yet, it brings about a level of destruction so immense as to mimic disaster itself.

Is it a coincidence, then, that Iki Design, the architectural practice who have designed and built Spine Tower for the Soma Group, are also closely involved in large-scale projects in several of Istanbul’s neighborhoods (including the infamous Fikirtepe itself) that have been earmarked as urban renewal areas? Surely not. In an economy driven by ruthless development, disaster and business are as intertwined in architecture as they are in mining.

Once, architecture was believed to be a socially motivated profession. But if now it is so inextricably intertwined with disaster, what might this entail for the future of architecture? A possible response to the question comes from an international bank that rejected the Soma Group’s application back in 2010 when the company were looking for loans to fund the construction of Spine Tower. Having discovered the origins of the Soma Group’s capital stock, the bank is reported to have replied that “there is too high a risk of workers’ deaths in the business of mining in Turkey, and we would not want to be associated with death.” Such risk assessment based on the principle of “the lesser evil” is now an essential part of not only the operations of the financial sector but also those around warfare, as Eyal Weizman shows. Following the disaster, the bank has enjoyed positive coverage whereas the skyscraper has become a venue for protest.

With all this in mind, it would seem that the more the destructive effects of architecture-as-(big)-business reflect those of war, the bigger a part of its workings is likely to be based on this principle.