The prevailing belief in a separation between humans and everything else is an essential function of a contemporary global economy which has permitted unprecedented levels of unsustainable resource extraction. The increasingly complex challenges human beings face in relation to the non-human world call for a paradigm shift: it is becoming ever more urgent to embrace new stories about ourselves and our relation to each other. This is the aim of ‘Stories on Earth’, Failed Architecture’s project for the parallel program of the Dutch Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 2021. Stories on Earth is an experiment which brings together spatial designers and writers to devise new spatial narratives that accommodate the inherent interrelationship between humans and the non-human. We selected three designers whose works challenge humans’ relationship with nature, and three writers with personal and professional connections with Caribbean storytelling.

As with the Biennale itself, our project was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, we think a proper introduction is still needed. We finally had a chance to meet our group of designers and writers and interview them. What follows is a faithful report of what was said, with a caveat: in line with the project’s emphasis on seeing the whole world as a living and breathing organism, we have sought to channel the collective voice of the group, focusing on their stories, ideas and opinions as a whole.

Can you tell us something about your background?

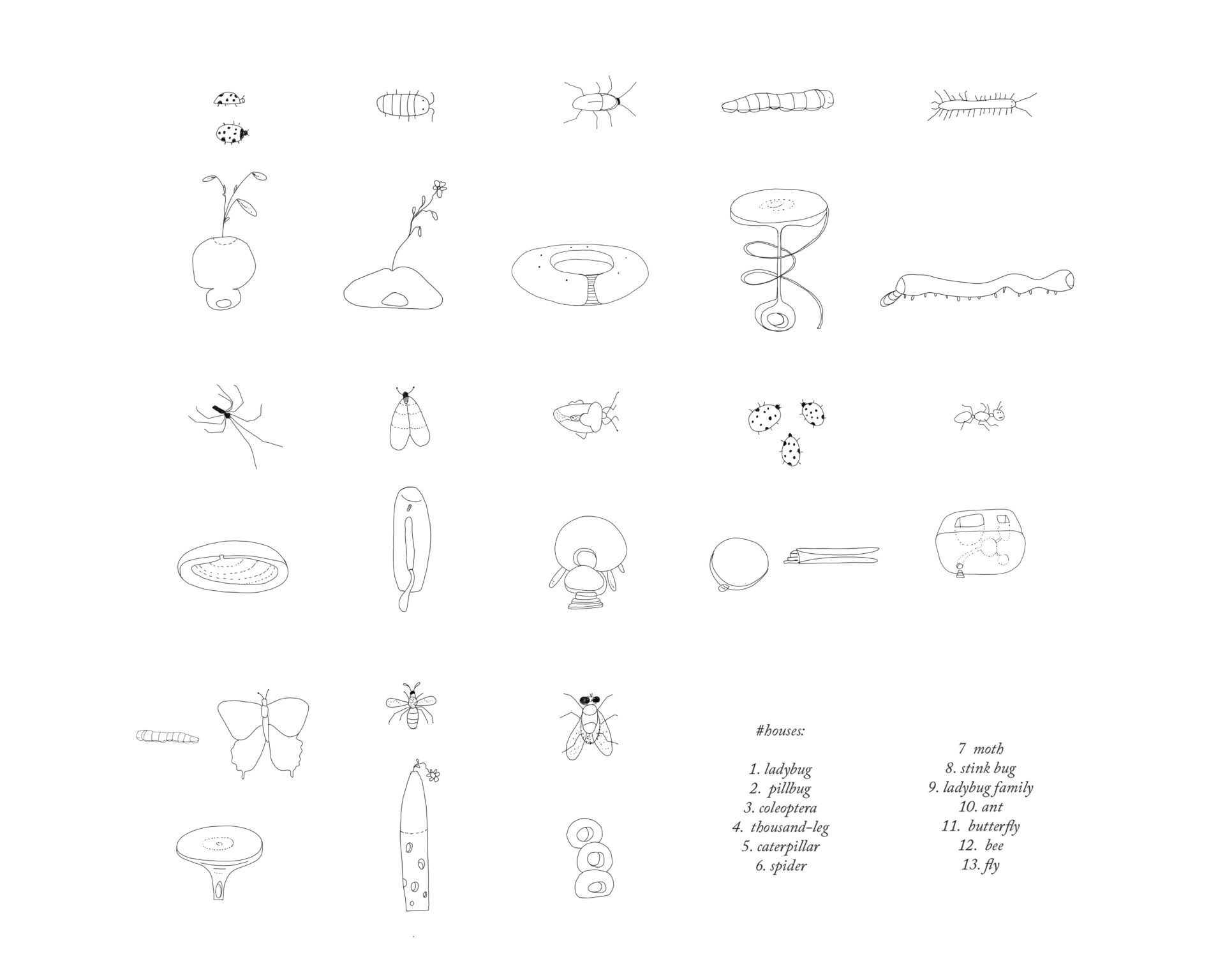

My background is coloured with many influences from different histories. I have studied in Delft, Amsterdam, Vienna, Florence and Porto. I’m an architect and landscape architect, an engaged writer, a poet and an entrepreneur. I have lived in both the Netherlands and Suriname in different periods of my life, and this has influenced my perspective on the relation between nature and human. My goal is to strengthen this relationship by designing narratives and making books that explore past, present and future ways of inhabiting the landscape. In my last project I designed thirteen small houses for the bugs and insects that inhabit people’s homes, to highlight the remarkable but often hidden diversity of domestic life. My practice also includes personal research, writing, zine and photography projects, specifically on the themes of urban renewal, displacement, traumatic heritages, and (personal) archives. Meanwhile, I have worked with Ngo’s, and acted as a cross cultural mediator for a diverse group of stakeholders and indigenous and maroon communities in Suriname, in the field of social and environmental development, employing participatory processes with a focus on nature, conservation, and climate justice.

“Stories on Earth” is, first and foremost, an attempt to challenge the narrative that pits nature against humanity. Is this a topic your work has previously touched upon, or something you were already interested in exploring professionally?

I have been always fascinated by nature and in particular by the idea of designing with nature. In my early childhood I learned to move silently in nature, without a trace. Often in spatial disciplines there is this divide between nature and culture, which can easily support the narrative of humans against nature, of separating humans and their actions from all other forms of being. But in my opinion such a divide doesn’t exist in itself. I have never felt it, and I believe that humans are a part of nature. Ecologies and affective relationships between species, as well as histories and timelines that connect one another, have always informed my work. In my experience, small observations in daily life are often a first step towards awareness of wider phenomena. That is why truly intersectional thinking doesn’t just stop at considering relationships between identities or individuations in the present, but rather considers histories and possible futures as well. I recently wrote a short story in Dutch called “Alles is Anana” (Everything is Anana) told largely from the perspective of the universal spirit Anana. She considers all living beings, humans, animals, trees and plants alike, as equals.

As a designer/writer you are probably very used to working alone. How important are professional collaborations to you?

As Erin Manning said in her beautiful, and very personal work A Perfect Mango: “I learned to compose with others for whom the collective is more than the sum of its parts. I learned to seed collaborations that welcomed a more-than-I, collaborations that could give life without reducing life to a single living being. I needed this: to be in excess of myself.”

I hardly ever work alone. Collaborations motivate me to come into action, instead of dwelling in the potential realm of possibilities. Working together creates something that could never be realised with just one pair of hands, one set of eyes, or one mind. I especially appreciate collaborations that go across disciplines and that allow projects to enter the realm of collective thought where ideas grow together and disciplines disappear. Yet, ‘professional’ always needs to be thought through critically, taken with a grain of salt, and the terms on which this professionalism is constituted must always be renegotiated in each new setting. Collaboration exceeds the professional, and often even the human. Then a project becomes much more part of life itself, opening towards new experiences that involve the whole body and create a very different kind of engagement that goes way beyond ‘work’.

The project is part of the Dutch Pavillion’s parallel program for the Architecture Venice Biennale 2020. The theme of the Biennale revolves around the question: “How will we live together?” What reflections does this question prompt for you?

I think “How will we live together?” is a really fundamental question. Sometimes it seems that contemporary architecture has forgotten that this is exactly what it is about. In these pandemic times, how do we cope with separation, distance, and change in a world where spaces and the gathering of people are under pressure? Considering the Dutch pavilion curators’ own follow-up question of “who is this ‘we’?”, I’d like to reflect on the notions of togetherness, solidarity, and community (with whom? for whom? where?) If “we” is interpreted as encompassing all living entities, and if we take the perspective of the astronaut, who sees the earth as one tiny beautiful unique spot in the vast universe, as a living organism floating in space with one atmosphere, one multifaceted ecosystem, and as one single whole, then the concept of borders and walls and exclusion are an obvious absurdity. I am part of the artists village Ruigoord and I have conducted some rituals and joined a couple of them. These rituals have always been contemporary rituals, things we designed ourselves sometimes with pagan influences. I have seen how this helped all the stubborn artists with all their different needs and opinions to meet and create a feeling of togetherness.

The Biennale might not take place because of the current COVID-19 pandemic. How did that influence your thoughts on these topics? [Note: when the interview was made the situation of the Biennale was still unclear. Now the Biennale has been postponed to 2021.]

I am quite surprised to see neither actions nor a strong stance from the curator of the Biennale in response to the current situation. Whether the biennale will take place or not, it won’t be like the past ones. The ‘will’ in the theme of the Biennale suggests an orientation towards the future, yet I think that times of uncertainty call for an approach more deeply rooted in the ‘now’. I guess though that this current ‘crisis’ fortunately brings about this necessary shift towards the present anyway. Maybe now more than ever we have the opportunity to raise this question within every realm of living together. This crisis has already made it clearer than ever that we share the same planet, air and public spaces. It has given us all an opportunity to reevaluate our freedom and the importance of human interaction. The excesses of the capitalist system have resulted in a worldwide health and economic crisis, and this crisis is deeply connected to the ways in which we occupy the spaces we live in. If we see it as the result of our disconnect with nature, it becomes an opportunity to reconnect, and move forward with each other.

Storytelling is a fundamental component of the project. What’s your personal and professional experience with stories and storytelling?

Storytelling is the basis of the written history of the Caribbean and a lively aspect of daily life there. This can also be seen in Caribbean poetry and theatre, where storytelling has different functions: a tool for survival, a means of expressing vulnerability, and a way to deal with injustice. My performances are stories, even my songs, my poems are stories. Stories (or toris, as they are called in Suriname) give us ways of understanding life. I am inspired by stories which give a voice to the voiceless, as well as stories which question more than they answer. I always look at my work as a form of storytelling: it helps me find the deeper purpose and meaning of the work. I usually prefer non-linear stories, which go not from A to B, but have an almost dreamlike quality, and try to express a feeling or a mood in an associative way, sketching inner landscapes in relation to their changing environment.

If you were to select a physical or virtual space where the dichotomy between human and nature is at its strongest, what would that be?

A zoo, the ‘Customs’ areas in airports, shopping centres with artificial nature, office buildings where people sit with headphones and walk with laptops, a city with no children where the sound of birds is rarely heard. In the city the presence of the human is so all-encompassing. Here nature often becomes something rather subtle, something one actively needs to look for all the time, and with this imbalance human and nature feel disconnected and the dichotomy is emphasised. In general I think this issue can be addressed basically everywhere. Definitely on our entire planet!

At some point in the past few months, we reached out to you and asked if you were interested in participating in this project, and you said yes. What was the most important reason behind your answer?

It gave me a good feeling. I work foremost with feeling. Gut feeling and intuition determine my choices. I am a curious person who likes to try out new things to learn new insights and meet new people. This project drew me in due to the possibilities for collaboration between different disciplines, to get new insight on what architecture could achieve or even mean when collaborating with a professional writer, and to make visible the role of storytelling beyond just the literary context. I have a personal interest in telling stories, and I liked the idea of having “multi species” as the basis of the brief. I’m glad for the opportunity to be part of the Biennale in some way, as I still see this exhibition as a great opportunity, but I am glad to do it with Failed Architecture, whose team adds a very much needed reflection to the discourse around the built environment, and allows me to be critical of Biennials. In particular I want to be cautious in respect to the relentless pace of production these manifestations ask from makers and workers in the art/architecture industry, especially precarious labour by freelancers and professionals who are just starting out.

Can you come up with a short fictional story about a society where human and nature are equal protagonists of life on Earth?

This is not fiction, but something we forgot. A story told to my mother, by my grandmother, and her mother’s mother. One day a big crisis hit humanity. It started with a virus.

A woman is dying in a park underneath her favorite tree. Afraid to let go of her life, she is comforted by the tree and a worm that lives underneath the tree.

Please, calm down.

They do not know about the warmth between us.

For them you were just a place to visit, for me you are my home.

We are one, entangled, we are kin.

The woman dies peacefully and becomes part of the cycle in which death brings new life: her remains are food for the worm, who ploughs the ground into fertile soil on which the tree blossoms with new leaves. We are one, entangled, we are kin.

It was the non-humans revolution. People decided to live together in symbiosis with all living beings on Earth. Plants and animals got the right to vote, and all actions of humans on the damaged planet started to be dedicated to mutual flourishing. And we lived happily ever after.

Anna Fink is a landscape architect, bookmaker and teacher. Her practice Atelier Fischbach focuses on artistic research around the narrative of landscape. She is investigating the notion of ‘topographic living’: a life in place and in close relationship with the environment. Anna’s goal is to strengthen this relationship through designing narratives and making books about past, present and future ways of inhabiting landscape. In 2018 Anna’s first book ‘Landscape as House’ was published by Architectura and Natura. One of her current projects is an embodied research called ‘The taskscape of the forest or how to live with forests (again)’. This ongoing investigation is aimed at unraveling the routines and rituals that shape the relationship between owners of small forests and their land.

Julien Ignacio is a writer, playwright, editorial member of literary magazine Tirade, and board member of the Carribean Working Group, an organisation focused on promoting Carribean literature in The Netherlands, Suriname and the Dutch Antilles. Julien recently published a short story called “GPS”. The story is based on the life of the Kurdish-Iranian writer Behrouz Boochani, who wrote the book No friends but the mountains, a report from Manus prison on a smartphone while held in detention on Manus, a small island off the Australian coast. Julien is currently working on his latest novel “VITA”, a futuristic love story set in a VR (Virtual Reality) world.

Karin Lachmising is a writer, poet and entrepreneur in the fields of Art, Culture, Sustainable Development and Environment. Karin’s debut poetry collection, “Nergens groeit een boom die haar aarde niet vindt” (There is nowhere a tree can grow that doesn’t find its soil) was published by In de Knipscheer, and her first monologue “Ode aan Helstone” was performed with the Nationale Volksmuziekschool and Youth Theater School On Stage Suriname. Karin has worked with indigenous and maroon communities in Suriname in the field of development and social and environmental change since 1985. Currently she teaches creative writing from a multicultural perspective as well as contributing as a moderator to Nature’s Narrative, a program of Pakhuis de Zwijger.

Setareh Noorani is an architect, researcher, zinester, and part of experimental music collective Zenevloed. In her projects and creative involvements, she uses various media to explore ways in unfolding and embodying, questioning processes of trauma and time, always in the grey space between academic and artistic research. This involves investigating, disrupting, and unfolding archives through spatial investigations and cathartic self-publishing practices. Her current research at Het Nieuwe Instituut focuses on qualitative, paradigm-shifting notions of decoloniality, feminisms, queer ecologies, agencies (non-institutional, non-authorship), and implications of the collective, more-than-human body in architecture, its heritage and its multivocal futures, as part of the new project Collecting Otherwise and the cross-institutional The Critical Visitor. Setareh holds a MSc in Architecture (cum laude) at TU Delft.

Roberta Petzoldt, a graduate of the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, is a transdisciplinary artist. She works from her studio at Ruigoord as a poet, performer, actress and visual artist. She has played two main roles in feature films by Eddy Terstall. She received the ‘Best Actress award’ at the 2015 Woodstock Film Festival. Roberta made her debut as a poet with Vruchtwatervuurlinie. This bundle has been awarded the Cees Buddingh Prize in 2019.

Angelo Renna is an architect with a keen interest in multi-species narratives, one he developed during his studies in Florence and Porto, and was further honed through collaborations with different offices, such as Stefano Boeri in Milan and Topotek in Berlin. Angelo is currently working on a research project called “Sweep Island” — a 3D printed artificial island located in the Meditteranean sea which will be able to increase marine life and collect microplastic. He has also just started writing his second book “what is nature?” following his first publication “Monkey Factor – small stories for a reconciliation with nature”.