This article is part of the FA special series Cities after Algorithms

In the not so distant future, when all of our physical and online activity is tracked by private corporations and the state, we will look back at 2021 as a time of relative privacy and freedom. In the UK, the Home Office’s use of data and surveillance in Immigration Enforcement, increasingly dependent on large-scale physical infrastructure supported by private corporations such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), should be seen as the canary in the coal mine, and a grave concern for all of us.

In 2012, then Home Secretary Theresa May announced she wanted to create a “really hostile environment for illegal migration”. The Acts of Parliament that followed compelled public and private bodies to check and monitor the immigration status of their customers, students, patients, and tenants. Immigrants unable to prove their “legal status” have since faced destitution and homelessness because they are denied access to housing, employment, banking, and healthcare.

That same year, Home Office immigration departments and the Police began working closely together to “streamline” immigration enforcement activities. They developed joint programmes such as Operation Nexus, which sought to deport so-called “High Harm” foreign national offenders (FNOs) and people even simply suspected of gang-related activity. These policies didn’t just impact those investigated, charged or prosecuted for criminal activity: up until 2018, the Police also scrutinised the immigration status of witnesses and victims of crimes. The result of the “Hostile Environment” was to subject those already racially marginalised to greater state violence and oppression. Far from aberrant, these practices are key totems to the U.K’s approach to immigration: deny vital services in order to deter “illegal migration”.

While the 2018 Windrush Scandal did briefly open up space for public scrutiny of many of these programmes, at the same time, the Home Office began investing millions of pounds in building new secret data infrastructure for increased immigration enforcement. Meanwhile, Home Office immigration departments and the Police began integrating their data infrastructure to create a more “streamlined” platform that could deliver live automated responses for immigration-related purposes. The new cross-departmental platform creates the possibility for complex surveillance, effectively extending the Hostile Environment into new realms. This evolution of the Hostile Environment requires a plethora of “extrastatecraft“ infrastructure. Mapping the spatial manifestations of this infrastructure, where information is stored and by whom, tracking its integration and movement, will therefore be integral to any future public critique and disruption.

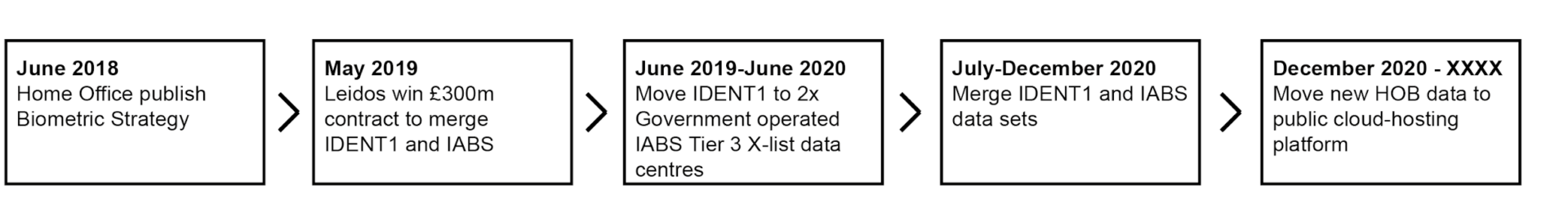

Prior to 2018, Home Office biometric data was decentralised, meaning particular departments such as the Police maintained ownership of the data it gathered and limited cross-departmental access to it. In June 2018, the Home Office published its Biometric Strategy and laid out its vision to overhaul how Home Office biometric data was owned, used and stored. A key project outlined in the document was to create a new centralised “Home Office Biometrics platform” (HOB), merging the Police IDENT1 and Immigration Enforcement IABS biometric databases. The HOB Platform aimed to fix individuals to a single biometric record (fingerprint, DNA, and facial imagery) which both Police and Immigration Enforcement could independently access and edit. This new system makes “illegal immigrants” biometrically legible for Immigration Enforcement.

Throughout the different stages of their integration to a single platform, the different databases were physically stored in publicly-owned, public-private partnership owned and ran, and entirely private data centres

IDENT1 is primarily a forensic fingerprint database system used by the Police. It contains the fingerprints of 7.1 million people in a covert location. In response to a Freedom of Information (FOI) request from 2018, the Immigration Enforcement Secretariat gave two reasons for keeping the database system private: 1. for the security of the individuals whose data is stored on the system. 2. to prevent cyber-attacks.

Although the explicit whereabouts of the infrastructure itself are classified, its previous location can be traced through a paper trail of legally required public notices such as tender and contract awards.

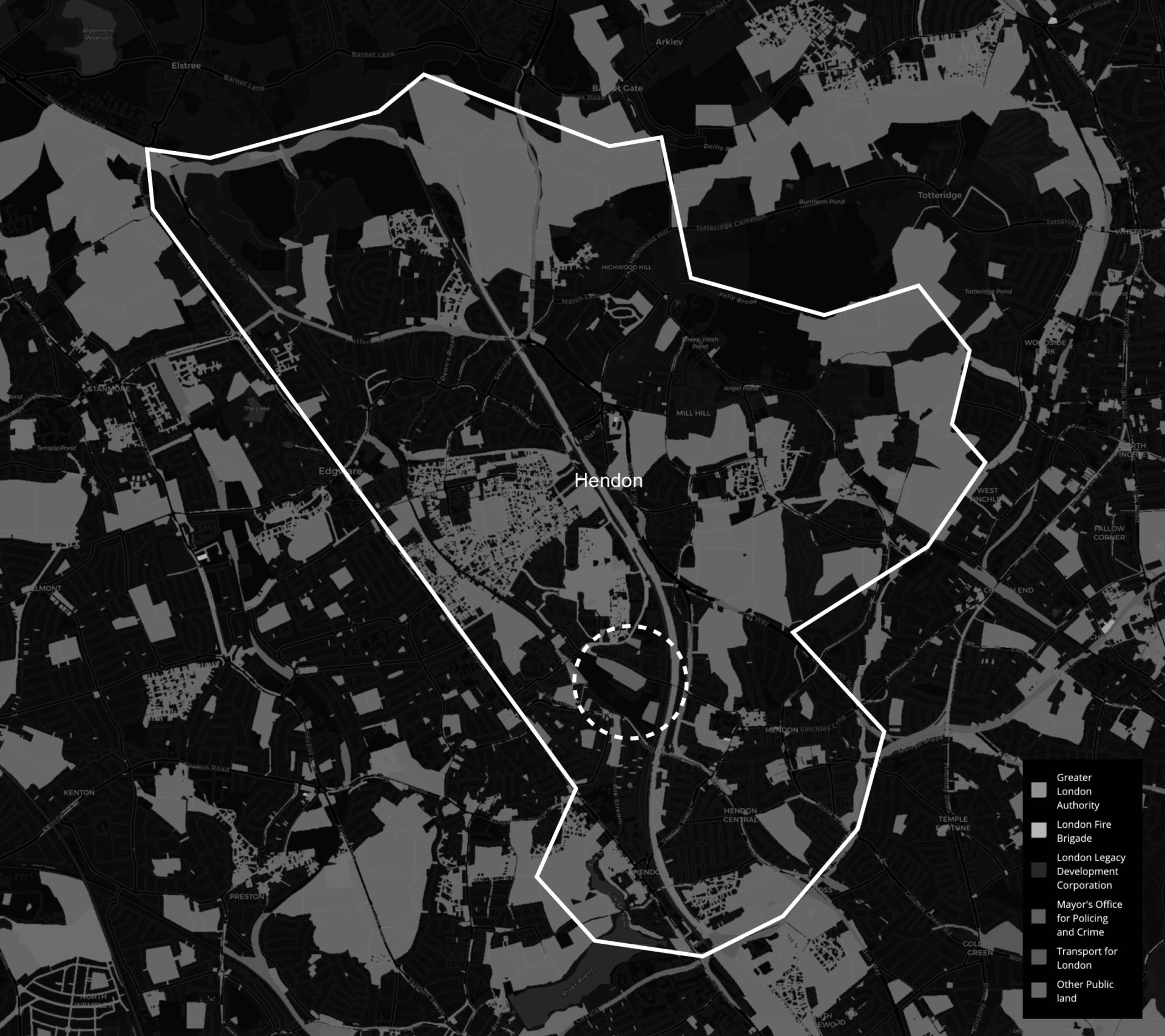

In 2018, private contractors began to disaggregate the IDENT1 system so that it could be effectively merged into the newly proposed centralised HOB platform. For the Government to employ private contractors they required public procurement, the rules of which are stringent. Through public tendering notices the IDENT1 system could be geographically located to the “Hendon Data Centre”. The work to disaggregate the IDENT1 system and then integrate it into the centralised HOB platform was tendered in the National Law Enforcement Data Programme (NLEDP) in 2016. In a job advert for the NLEDP, it gave the specific location for the work: “Hendon Data Centre”. Therefore we can directly link the IDENT1 database to the Hendon Data Centre, however, the precise address requires further investigation through other sources.

In 2016, City Hall’s London Land Commission produced a comprehensive register and map of London’s publicly-owned land. Zooming into the London Borough of Hendon, there is only one large site owned by the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime. Therefore, it can be circumstantially presumed that this location is likely the site of Hendon Data Centre for which the IDENT1 database was stored.

Map created using the Public Land Registry, showing publicly-owned land in Hendon. The circled area highlights the area of interest, an industrial estate owned by the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime.

Inspecting aerial photographs, we can observe that the site is occupied by several buildings. Data centres are identifiable not by their architectural language (they don’t want to draw attention to themselves) but by unusual combinations of power, cooling and security components. We can therefore precisely identify Hendon Data Centre in the image below: hidden behind reflective glazing and a fortified fence and housed in an industrial shed. Five cooling modules sit discreetly set-back on its roof, generators, substations and transformers occupy the immediate grounds, it is highly-secured with mantrap airlock cylinder gates and 24hr on-site security. Its primary entrance faces away from the public street, and instead into the privately-owned grounds of the Metropolitan Police Training Centre.

Integrating Home Office immigration department data with the Police gives greater powers for immigration surveillance and enforcement. The Police are already testing technology to identify people using voice and facial imagery. By integrating Home Office biometric information, Automatic Facial Recognition cameras could effectively be deployed in public environments and be used to identify “illegal immigrant” targets. Seemingly innocuous or procedural database integration in practice opens up an expansive toolset for a wide range of abuses to our civil liberties. As these databases are integrated, enmeshing policing and immigration powers, and dependent on public-private partnerships, they simultaneously become harder to track.

By tracking the IDENT1 database and where it has been physically stored, we can see that the Hostile Environment makes itself visible not just by its effects on those caught in its grasp, but also through a network of formal relationships, legal contracts and obligations. Its power comes directly from the judicial system, the police, and prisons but also from its ability to keep “secret” key infrastructure that is relied on for its functioning. Making that infrastructure visible de-stabilises it, both politically and technologically. If its existence is known, it can be disrupted: by being vulnerable to attack, technologically or politically: for example, protesters could physically target or even sabotage key nodes of its functioning.

After being disaggregated, the IDENT1 database was moved from Hendon Data Centre and integrated with the Immigration and Asylum Biometrics System (IABS) to form the centralised Home Office Biometric platform (HOB). The IABS is the main immigration biometrics database used by Immigration Enforcement, Border Force, and UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) which contains fingerprints, DNA, and facial imagery. The Home Office Biometric platform (HOB) combines the IABS with the biometric IDENT1 database to provide Police and Immigration Enforcement with a central integrated system for dual purposes. The geographical location of this new system is not publicly advertised.

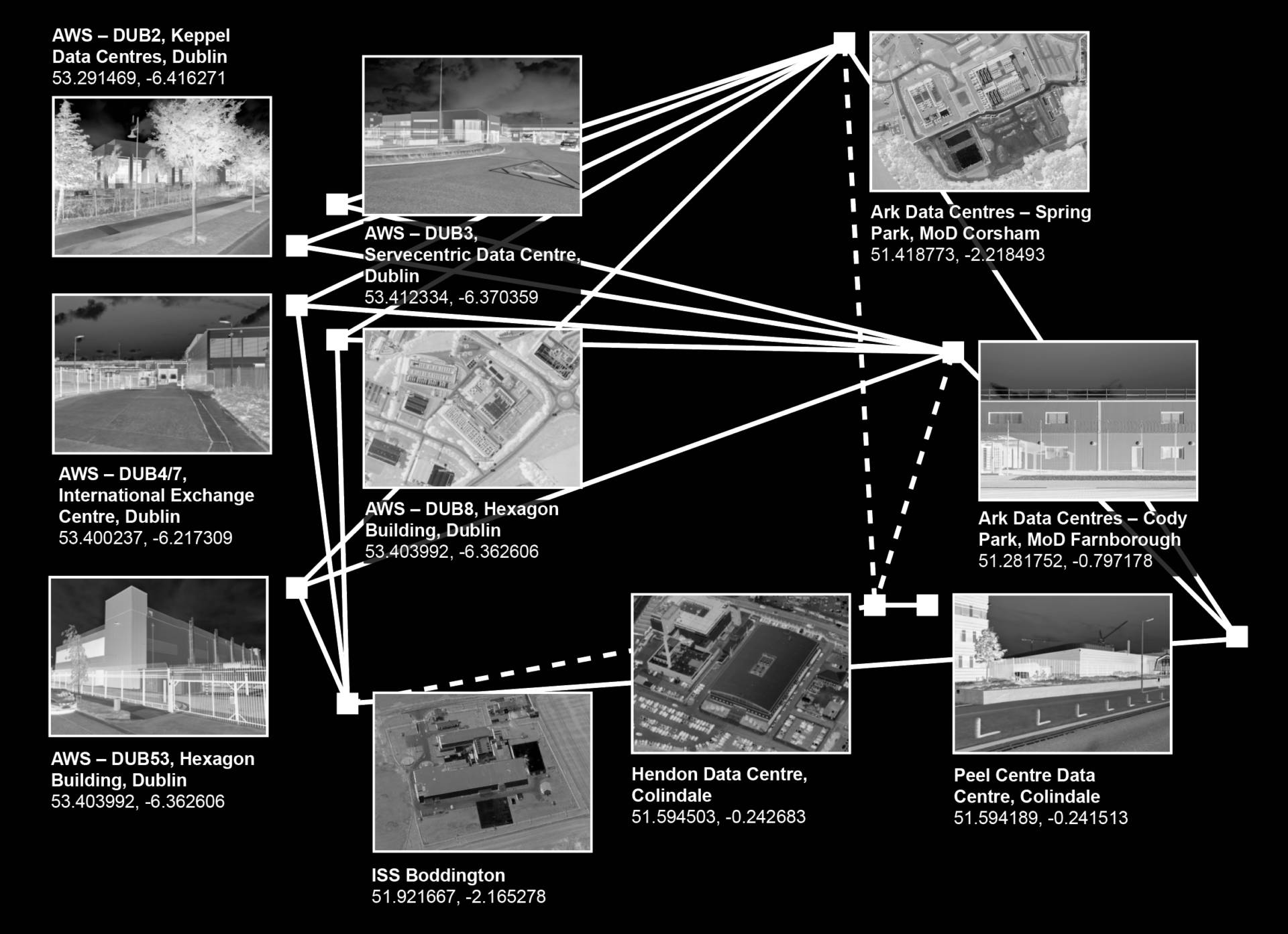

However, a Contract Award Notice released by the Home Secretary in 2019 states that the IDENT1 and IABS systems would be moved to two Crown Hosting Data Centres. Crown Hosting Data Centres, is a joint venture between the Cabinet Office and Ark Data Centres. In a 2018 press release, the Cabinet Office announced that the Crown Hosting Data Centres would be located in Spring Park, Corsham, Wiltshire formerly part of RAF Rudloe Manor South. Since the 2018 announcement, another Ark Data Centre was built on another former Ministry of Defence site in Cody Park, Farnborough. Both of these sites host multiple data centres so the exact location of the HOB cannot be precisely determined.

The Home Office is in contract with Amazon Web Services (AWS) to move all of its systems onto a Public Cloud-platform to improve efficiency, service performance and security. The new system is built around three availability zones in London and Dublin. AWS simultaneously co-locates out of data centres owned by other companies and operates their own data centres, but they obscure their relationship to it by using company pseudonyms such as “VaData, Inc.” or “Vandalay Industries”. In 2018, Wikileaks published a “highly confidential” AWS internal document from 2015 detailing the addresses and operational details of over one hundred AWS data centres including those in Dublin, but no information about the London data centre is publicly available. The HOB will soon be stored in these three AWS data centre regions, thereby rendering the system completely invisible, and further obscuring it from public scrutiny.

Besides the lack of transparency and accountability, the transfer and privatisation of critical technological infrastructure should in itself be of public concern. Using a public cloud platform means the cloud service provider (AWS in this case) is entirely responsible for that system. Given that AWS operates as a U.S. company, it is subject to the 2018 Cloud Act which means it can be secretly subpoenaed in the U.S, and AWS would be legally required to hand over data, potentially detailing the biometric information of people in the UK, to US Government agencies such as the National Security Agency (NSA).

Methods to disrupt the Hostile Environment rely first on making visible what is hidden, exposing the black spots on our radar: whether it be identifying where and when immigration enforcement is happening in order to obstruct raids, or exposing secret night-time charter flights to plot runway blockades and leverage public attention, litigating against human rights violations, or just knowing how immigration systems work in order that immigrants are better equipped to navigate public life safely. If technology (and specifically data infrastructure) is at the forefront of advancements in immigration enforcement capabilities, how do we first make visible aspects of the system that authorities want to keep hidden?

As explored earlier, privatised data infrastructure is currently subject to less strict public transparency laws, so the task of “making visible” the hardware of the Hostile Environment is much harder. Perhaps workers employed or contracted by private corporations are the key to uncovering this hardware. For example, employees within an AWS data centre are privy to confidential information. Given Amazon’s strategic importance in the global economy, there have been multiple efforts to organise Amazon workers. In March 2021, Unite the Union launched a hotline for Amazon Workers in the U.K. Given that Amazon makes more revenue from AWS than its retail business, trade unions like Unite would do well to increase efforts to organise workers who service AWS data centres.

Organiser Jane MacAlevey in her book No Shortcuts says: “a divided approach to workplaces and communities prevents people and movements from winning more significant victories and building power”. Expanding the scope of trade union organising beyond a narrow focus on pay and conditions also improves the chances of success since it engages a wider range of affected communities. In July 2019, Amazon workers in New York protested with local activists to highlight technology they were being asked to develop that was later sold to the U.S Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Similar methods could likewise offer critical resistance to the U.K.’s Hostile Environment policies: uniting workers in data centres, workers who design and construct the data infrastructure, and precarious immigrants at risk of deportation.

Whether or not trade union organising can be weaponized against the Hostile Environment remains to be seen. What is known is that the U.K Government is investing heavily in transforming the data infrastructure of the Hostile Environment so that different government departments can work even closer together for immigration-related purposes. The project to map the physical data infrastructure supporting the Hostile environment could prove an important tool to focus these organising efforts. Otherwise, the U.K. risks becoming one big datasphere where immigrants are ever-increasingly surveilled and deported en masse.

The FA special series Cities After Algorithms is produced in collaboration with the design research initiative Aesthetics of Exclusion, and supported by the Dutch Creative Industries Fund.