The Venice Biennale 2021, curated by Hashim Sarkis, asked the question “How Will We Live Together?”. In light of the widening cultural and economic divides of our era, Sarkis challenged the participants to explore how architects can create inclusive and equal spaces. With this question in mind, renowned Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena and his firm Elemental presented the Koyaüwe. This outdoor installation is a circular courtyard confined by a loose palisade wall of tall timbers interwoven by shorter logs, forming a tree trunk-like shape. Elemental described it as a neutral stage where Mapuche leaders, Chile’s largest indigenous community at around 12% of the population, and the corporate representatives of the timber company Arauco would meet and alleviate a decades-old conflict over land ownership—at least until the pandemic upended any travel plans. What Elemental fails to mention is they are not a neutral arbiter, possessing a long-standing partnership with the Chilean mega-conglomerate AntarChile who’s part owner of both Elemental and Arauco.

Koyaüwe, which translates from Mapuche to “places to parley,” draws inspiration from historical parliaments (peace treaties). These parliaments occurred primarily in the 16th and 17th century during the Spanish Empire’s unsuccessful attempts to conquer the Mapuche homeland in south-central Chile. While Elemental finds its inspiration in the distant past, it is critical to understand the recent history that the firm’s narrative eludes. The modern Mapuche struggle and Elemental’s owners direct relation to it, exposes the contradictions and limitations in the firm’s corporate approach to “socially-aware” architecture.

Like most indigenous groups in the Americas, many modern Mapuche face chronic poverty and discrimination—the result of a long crushing process of settler colonialism which began as border conflicts with the Spanish Empire and escalated to outright annexation by Chile in the 19th century. With the end of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1990, Mapuche activists created autonomist movements, seeking land reclamation alongside some form of independence from Chile. What began as scattered protests and land occupations in the late 1990s escalated in the past decade. Mapuche groups have been accused of robbery, sabotage and arson, particularly against large landowning companies in the region like Arauco. The Chilean government’s efforts to protect its corporate partners has only fanned the flames. Modern Chile still relies on the tools left by the Pinochet regime to brutalize Mapuche activists, primarily militarized police and the infamous 1984 anti-terrorism law, earning the persistent criticism of global human rights observers. In this context, Aravena hopes his architecture can play some role in a peaceful resolution.

Street art in Santiago created after the civil unrest of October 2019, illustrating of the face of Camilo Catrillanca a young Mapuche organizer murdered by the police.

Felvalen, Wikimedia Commons

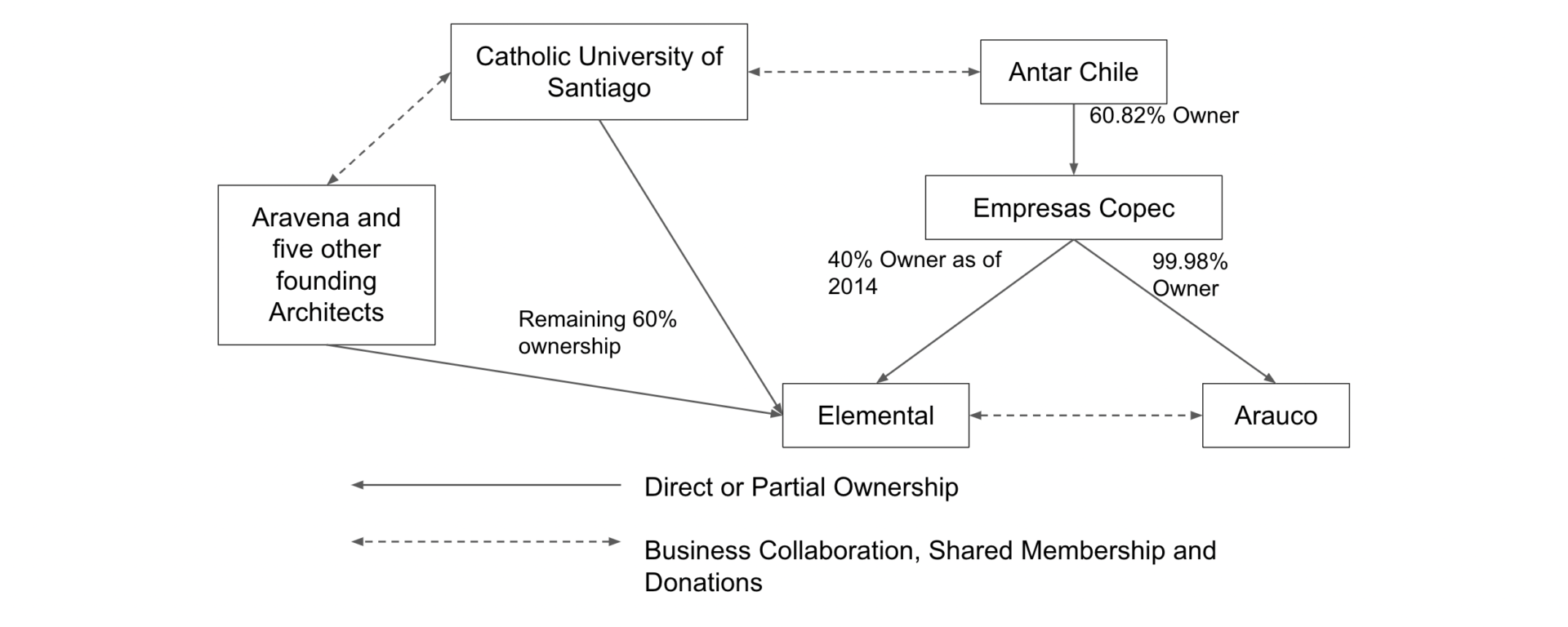

Since his rise to international fame in the 2010s, Aravena and his “Do Tank” firm Elemental have maintained a reputation for “socially engaged” architecture. Aravena is commonly cited as an example of the architectural zeitgeist’s renewed interest in practicality and social good in opposition to the wasteful and ego-centered starchitecture of recent decades. This is largely owed to Aravena’s reliance on a direct corporate partnership with AntarChile. The company’s patronage provides both financial backing and political connections that undergird Elemental’s social projects like public housing. While undoubtedly successful for Elemental, this arrangement is a conflict of interest when Aravena presents his firm as a neutral arbiter for problems and projects AntarChile is directly involved in.

Elemental has produced a number of critically acclaimed designs, particularly for their social housing projects and work with their organizational partners, the Catholic University of Santiago. Yet, one of its most famous projects dealt with Arauco. Elemental re-designed the streets, public buildings, and private homes of the small central Chilean city of Consitución after a tsunami devastated it in 2010. Arauco funded much of the reconstruction effort, being the owner of the city’s massive paper mill. This effort won Elemental significant acclaim, particularly for the firm’s emphasis on heeding input from residents while pursuing innovative, cost-efficient designs. Aravena was able to negotiate some productive compromises when interests butted heads. Commonly cited was the debate over the damaged Constitución paper mill. Some residents, bothered by the pollution and steam the mill produced, hoped reconstruction involved a plan to move the plant rather than repair it. When Arauco, instead, threatened to leave the region entirely, Aravena, serving as negotiator, got the company to agree to odor reductions and steam reuse. It seems that both Arauco and Elemental are attempting to re-create their previous success as they now engage with the much thornier Mapuche conflict.

Elemental’s work with Arauco in Araucanía, the region comprising much of the former Mapuche territory, began back in 2019. The Künu, Mapuche for “places to know each other”, was constructed that year in the Chilean city of Loncoche. This larger structure is older brother to the Koyaüwe in Venice, a field partly encircled by the same Mapuche inspired timber palisade. The structure serves as the first component of a new Mapuche cultural center, largely funded by Arauco, as a path to rapprochement with the Mapuche community.

While both the Koyaüwe and Künu aspire to be common grounds for negotiations between Arauco and the Mapuche, their land, materials, and much of their financing were provided by only one side of the “negotiators”—Arauco. Aravena is well aware of this issue, claiming in one 2021 interview that all of his projects, in principle, carry some necessary conflict of interest. This interview also features Juan Mila, the leader of the Loncoche Mapuche Association, who admits that criticism of the project by other Mapuche largely stem from this connection to Arauco. Like in Constitución, the Künu’s design used the input of local Mapuche, particularly relating to its orientation and shape. Despite this local participation, it is worth considering how the Künu project, like the reconstruction of Consitución, was likely constrained by the specific design options presented by Elemental and defined by Arauco.

In another promotional interview, Aravena proclaims, “We are not the protagonists, Architecture is just the background”. Aravena recognizes that Architecture, reliant on a society’s existing modes of social and physical construction, often struggles to directly affect social change. This is particularly the case for Elemental, constrained by AntarChile’s narrow interests. Aravena strives for symbolic neutrality, allowing his architecture to at least serve as the stage for positive social change to occur. While this methodology applies well to something like a college campus building, it falls short when the explicit purpose of the project is to engage with a systemic injustice like those suffered by the Mapuche. Reducing the scope of the Koyaüwe and Künu to a historically neutral backdrop assumes an equality of power and aggrievement between the actors.

Aravena treads carefully when discussing the actual parties or specific reasons for the modern Mapuche conflict. In a promotional video, he states “Mapuche and Chileans have always been in conflict” and that “At the core is the question of land. Be it for legal, political, or cultural reasons, the fact is that violence has escalated.” Overall, Aravena places most of the blame for the Mapuche conflict on an abstract national animus. In reality, while the conflict is rooted in racial oppression, it is not some eternal blood feud. Only 50 years ago the “question of land” seemed on a path towards resolution, a path quickly reversed in the interest of Elemental’s part owners.

What began in the 1900s for Mapuche organizations as a performative and often paternalist relationship with the left became a fruitful alliance with the election of Salvador Allende and the Popular Unity Coalition (UP) in 1970. In their first few years, the socialist Allende government passed multicultural reforms and a new indigenous law that for the first time legally recognized the rights of Mapuche citizens. Pressured by their Mapuche allies, the UP then drastically accelerated the limited program of land expropriation begun under the prior progressive government. Under the UP, around 100,000 hectares were returned to Mapuche communities.

When the Pinochet regime seized power in 1973, they quickly reversed the programs and expropriations implemented by the UP, providing innumerable rewards to allies like Anacleto Angelini, founder of AntarChile. The rapid process of land reprivatization left only 16% of the recovered Mapuche territory. Any resistance was met with the regime’s characteristic brutality. Farmed Mapuche land was divided among individual peasant owners who, unable to compete with larger mechanized operations, often sold to large firms. Poorer land was either purchased from desperate Mapuche or directly transferred to the National Forestry Corporation and then sold to lumber companies. At the same time, the regime massively expanded the government subsidy for forestry plantations offering further land grants, tax exemptions and aid in labor recruitment, mostly from poor Mapuche communities. This was how Arauco and by extension AntarChile managed to acquire vast swaths of Chile and the Mapuche’s land at significant discount. As of 2014 the firm owned around 44% of the Chilean timber market, one of Chile’s largest exports. In a writeup, Aravena indicates that the actions of the Pinochet regime helped exacerbate tensions with the Mapuche, yet he never mentions how AntarChile and Arauco were direct beneficiaries of those policies. Additionally, a singular focus on solely the land dispossession, ignores how the ecological destruction wrought by companies including Arauco worsens the Mapuche’s situation.

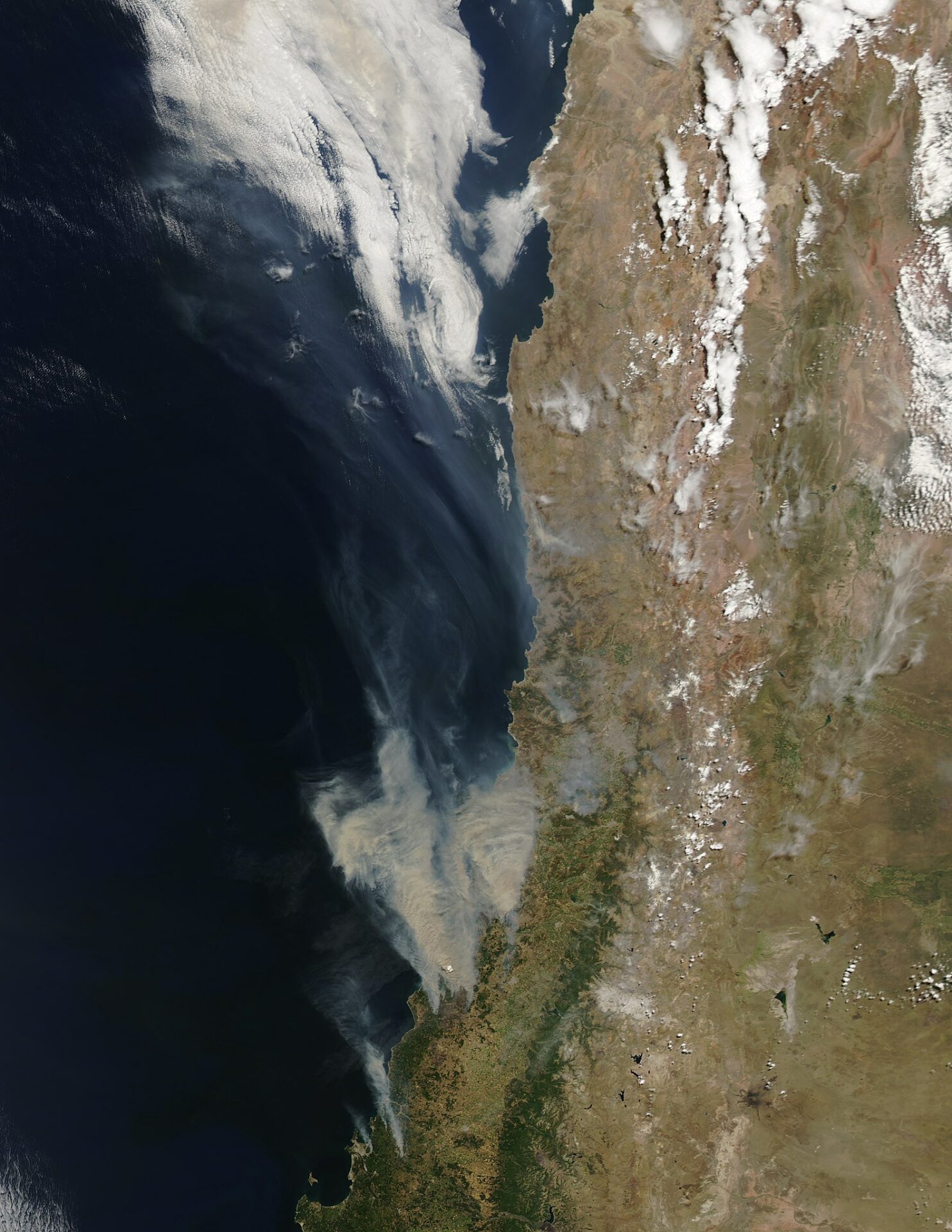

The ecological effects of European style land management have ravaged south-central Chile. The region, once blanketed by temperate forests, quickly became a patchwork of flood-prone clearings, thanks to both the Chilean-run timber companies and farms, as well as the intensification of ranching in remaining Mapuche lands. The subsidized growth of the forestry industry and the current climate collapse further stress the ecosystem. The massive plantations are dominated by monocultures of mainly non-native Monterey Pine and Eucalyptus. As exotic species, they serve little function in the natural environment compared to their native counterparts, eliminating natural habitat. Worst of all, these trees planted as tight monocultures easily catch fire, something rare in natural Chilean forests, worsening with each abnormally dry year. Forest fires and their smoke are now a common hazard for Mapuche working on or living near Arauco’s plantations.

One possible reason for Arauco’s collaboration with Elemental on the Mapuche Conflict is preparation for larger political changes. Parallel to escalating violence in Chile’s rural south, the past few years saw massive urban left-wing protests, broadly arrayed against the same neoliberal capitalist regime the Mapuche suffer under. The ongoing constitutional convention brought about by these protests was first led by Elisa Loncón, a prominent Mapuche activist. Aravena was a guest speaker at the convention last year, presenting Elemental’s work, and by extension AntarChile’s, as a solution to Chile’s myriad problems. More recently, one of the protest leaders, Gabriel Boric, became Chile’s new president. Boric has been publically supportive of the Mapuche cause, pledging to end his corporatist predecessor’s military deployments to Mapuche territory, and on his first day in office met with leaders of the Mapuche and other indigenous groups emphasizing a new “Pluralnational” identity for Chile. While the future of both the Mapuche and the new Chilean government remains uncertain, there is potential to reforge the Left-Mapuche alliance of the Allende years. With these conditions, it is reasonable for companies like Arauco to make a public pitch towards reconciliation.

Photo of a 2019 pro-mapuche march in San Antonio Chile.

Vivian Morales C., Wikimedia Commons

Current events—the pandemic or Chile’s potential political revolution—seem to outpace Elemental’s Koyaüwe. It reveals a key limitation to Elemental’s architectural method. Above specific ethical compromises, direct corporate patronage inevitably limits the ambition and direction of a project. While less of an issue for more infrastructural programs, it shines through somewhere like the Biennale, where artistic statement is the core premise. At this critical moment, in both Chile and the Mapuche’s history, the Koyaüwe had the opportunity to present the Mapuche’s struggle to the world. In the interest of his patrons, Aravena thrusts that history, with its many defeats, scattered victories, and innumerable casualties into a symbolically neutral historical, architectural backdrop.