Urban and architectural decay appeals to the imagination. While some consider the unfinished or collapsing parts of the city as ugly or disturbing, others feel they make an area more interesting than the picture perfect urban fabric. The city’s scars are stimuli for the mind. They raise questions, about memories and imaginations of a foregone past, and of potential futures. They visualise the passage of time and the inevitability of collapse, reminding us of our own transience. On a smaller level, dilapidation shows traces of faded lives, moved communities and shrunken economies. The voids provide space for the observer to interpret them as she or he likes, to fill them with imaginations and meanings.

Decay is a process rather than a fixed image and provokes thoughts and actions. It is not in sync with progress, modernisation and determined narratives, which are characteristics of modern Western society. Not surprisingly, decay is a main creative inspiration for artists and writers.

Not a new thing

The fascination with these spaces is widespread and perennial. Decaying structures, derelict places, abandoned lots and other urban imperfections have been the inspiration for many artists and writers since long ago. This goes back to Piranesi’s depictions of Rome and Hubert’s one of the Louvre’s Gallery as a ruin in the 18th century, was present with Joseph Gandy who painted the Bank of England after its fictional destruction, in John Ruskin’s writing about historic preservation and that of Sigmund Freud in Civilization and its Discontents, and continues with Walter Benjamin using ruins as allegory, and Rose Macaulay’s The Pleasure of Ruins. These are only a handful cases in which decay influenced well-known writers and artists. The notion of decay also influenced architects, the famous example being Hitler’s master builder Albert Speer, who in his theory of Ruin Value stressed that a grand design should degenerate beautifully over time. In fact, when designing Germania, he was already taking into account how it would look as a ruin, as a monument of the past, resembling the greatness of the Roman empire.

21st century literature

But the obsession is not something of the past. In recent years, much literature about the topic has been published, trying to explain why the ruin prompts such instinctive responses in us that are filled with melancholia, nostalgia and imagination.

Examples are Christopher Woodward’s In Ruins, Brian Dillon’s Ruins, Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle’s Ruins of Modernity, and many single articles, such as Reckoning with Ruins which was written by Caitlin DeSilvey and Tim Edensor. In Explore Everything, Bradley Garrett dives into the world of urban exploration (the accessing and trespassing of ruins and structures to which entrance is forbidden) and explains that its attraction to a large extent has to do with a fascination with dereliction. He writes that ‘Ruins may be decaying, they are not dead, they are filled with possibilities for wondrous adventure, inspiring visions, quiet moments, peripatetic playfulness, dystopic preparation and artistic potential’. In general, the literature shows a gradually shifting attention from the classical ruins to modern ruins. These are roughly the ruins that emanate from industrialisation and urbanisation from the 19th century onward.

Photography

Also in the arts the preoccupation with urban voids has increased, not in the last place in photography. Everyone at least knows someone who is active in urban exploration, secretly entering abandoned structures, and capturing them in photo. Photographers have made it to the reputable museums and galleries with series depicting abandonment, decay and emptiness, showing the collapse of the futures of the past and the metaphoric resonances of voids (and sometimes being accused of engaging in “ruin porn”). These photographers include and Yves Marchand & Romain Meffre who became superstars with their work on Detroit, Andrew Moore, who shot the decay of New York, Detroit and other places, Simon Marsden who captured ruins as haunted sites, Steven Siegel showing New York’s decay in the 1980sand Shaun O’Boyle who documented America’s 20th century flip side.

Ruin art

Also in the arts, a growing interest in ruins and leftover space is manifest. The notion of failed modernist utopia is not seldom a topic in contemporary works of art. Artists such as Karin Kihlberg and Reuben Henry, and Cyprien Gaillard refer to decay, transience, destruction and ruination in their work, not seldom referring to rationally designed cities and buildings. German artist Tilmann Meyer-Faje investigates (and manipulates) the transformation and eventual collapse of structures in his ceramic sculptures, mostly modelled after prefabricated modernist architecture. He looks at the architectural object as a process, which therefore also includes its inevitable decay.

Voids

Italian-born architect Simone Pizzagalli has an interesting take on the notion of decay, leftover space and voids. In his Archiprix-winning essay Space, Poetics and Voids, he underlines the narrative importance of voids. In the essay, he draws the parallel between language and space (via cinema), in order to show that the city can be interpreted as an arrangement, a sequence, in which the void has an important place. In language, silence is an meaningful component that carries culture, history and tradition. Pizzagalli writes that in spoken language, “silence becomes a space more than a real void, a pause that is absence of sound but enriched by a tension of meaning, in itself as silence, or in relation with what was before and after”. In written language, voids between words, lines, paragraphs and chapters, the reader can fill in his own meanings and realities. He quotes Italo Calvino who writes in Invisible Cities that Kublai Khan likes to wander through the voids not filled with words, “become lost, stop and enjoy the cool air, or run off”. He connects the thoughts of Roland Barthes, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Albert Camus and others to support his own. The essay has now been transformed into a beautiful publication, designed in sync with the contents, visually showing narratives, rhythms and tensions in text, colour and illustrations.

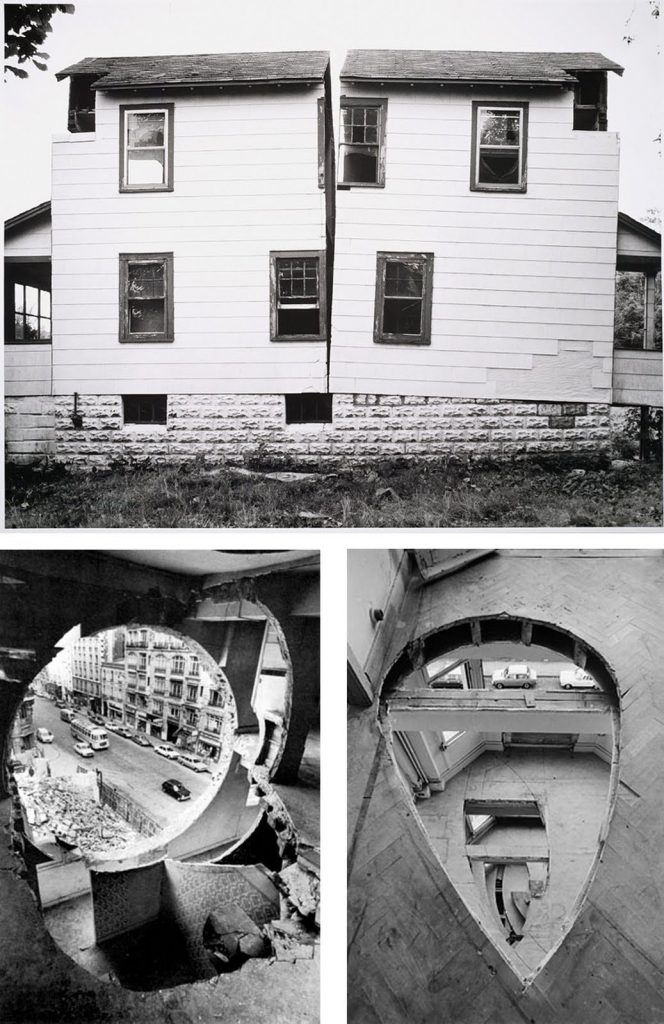

Isolated vestiges from the work “Office Baroque” (1977) as seen in one of the pictures above, taken from a building in Antwerp that was demolished after Matta-Clark worked on it. On display at Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin.

Mark Minkjan

Pizzagalli eventually ends up at space and the built environment, where voids are not a lack, not nothing. They are important elements that help us interpret the space around us. He has a particular interest in Gordon Matta-Clark, who did not just use the void as a building block in his works of art, he created voids himself as an act of preservation. He physically cut buildings that were about to be demolished. By creating the void, Matta-Clark charged the structure with a certain tension, leaving an impression in the mind of the observer and by doing so, preserving the building.

A somewhat similar act was done by the artist Seamus Nolan work at Dublin’s Hotel Ballymun in 2007. In the month prior to the demolition of the Clarke Tower, one of the last remaining high-rises in Ballymun, its 15th floor served as a hotel, offering nine hotel rooms. Simultaneously, a programme of art, performances, debates and social events took place. The project encouraged the visitors and spectators to reconsider the building, making it leave an impression and go out with a bang instead of quietly disappearing.

In his essay, Simone Pizzagalli says: “void contains in itself all the potential of the space, all the relation not written and experienced. [..] Void is the place of tension of something that will be, a space in power, but also the only place where the recollection of reality, the composition of the parts, fragments, of life can happen.”

These imperfect, incomplete, broken and illusionary fragments of the built environment are important components of narration. They connect people, places, histories and futures. They will surely remain the creative inspiration for many.

Header image: Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre