This article is part of the FA special series Everywhere Walls, Borders, Prisons.

Inside the leisure centre is the swimming pool; 25 metres of water with six lanes for lessons and casual swims. The room reverberates with echoing splashes, laughter, and chatter. It smells of thick chlorine and crisp packets. Ibz* used to come here regularly; the pool was local to where he lived in Sunderland, and he liked the exercise and community it offered. However, from 2014 to 2016 Ibz was electronically tagged by the Home Office (the UK’s Government department for immigration) and so he felt no longer able to swim. He tells me over the phone: “I enjoy swimming and I wanted to swim, but I couldn’t wear shorts because then people would see me and see my tag. I didn’t want people looking at me.” For 891 days he never went back to the pool. Instead, he stayed inside his flat and waited.

In North East England where the City of Sunderland is located, 30 out of every 100,000 people are electronically tagged by the State – many of them migrants seeking asylum. This tagging phenomenon happens nation-wide, and should be recognized as yet another government strategy designed to isolate and exclude people born outside the UK. It’s part of a broader set of policies called “The Hostile Environment,” which make it as difficult as possible for migrants to build a life and community in this country. By extending its governance to the control of everyday mobility, the state shuts people on tag out from neighbourhoods and cities.

The blueprint for The Hostile Environment began to take shape in 2004. Responding to a rise in asylum applications and xenophobic pressures from the media, the purportedly left-leaning Labour government introduced the Asylum and Immigration Act. This limited migrants’ right to appeal against deportation decisions, stripped state support (like benefits and housing) from those who didn’t cooperate with the deportation process, and began the electronic tagging of migrants awaiting deportation. When the right-wing Conservative Party was later elected, these ostracising measures became even more extreme. In the 2014 Immigration Act, Home Secretary Theresa May banned migrants from taking up employment or accessing state support, and in the 2016 Immigration Act she legislated for electronic tags to be fitted on anyone awaiting deportation proceedings. By June 2022, her successor, the Conservative Home Secretary Priti Patel, imposed tagging on all migrants who arrive in the UK via “unnecessary and dangerous routes,” according to the government’s June 2024 report Electronic Monitoring Statistics. In 2016, the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration found that the expansion of tagging is a political tactic to make life so “hostile” for migrants that they “voluntarily” choose deportation.

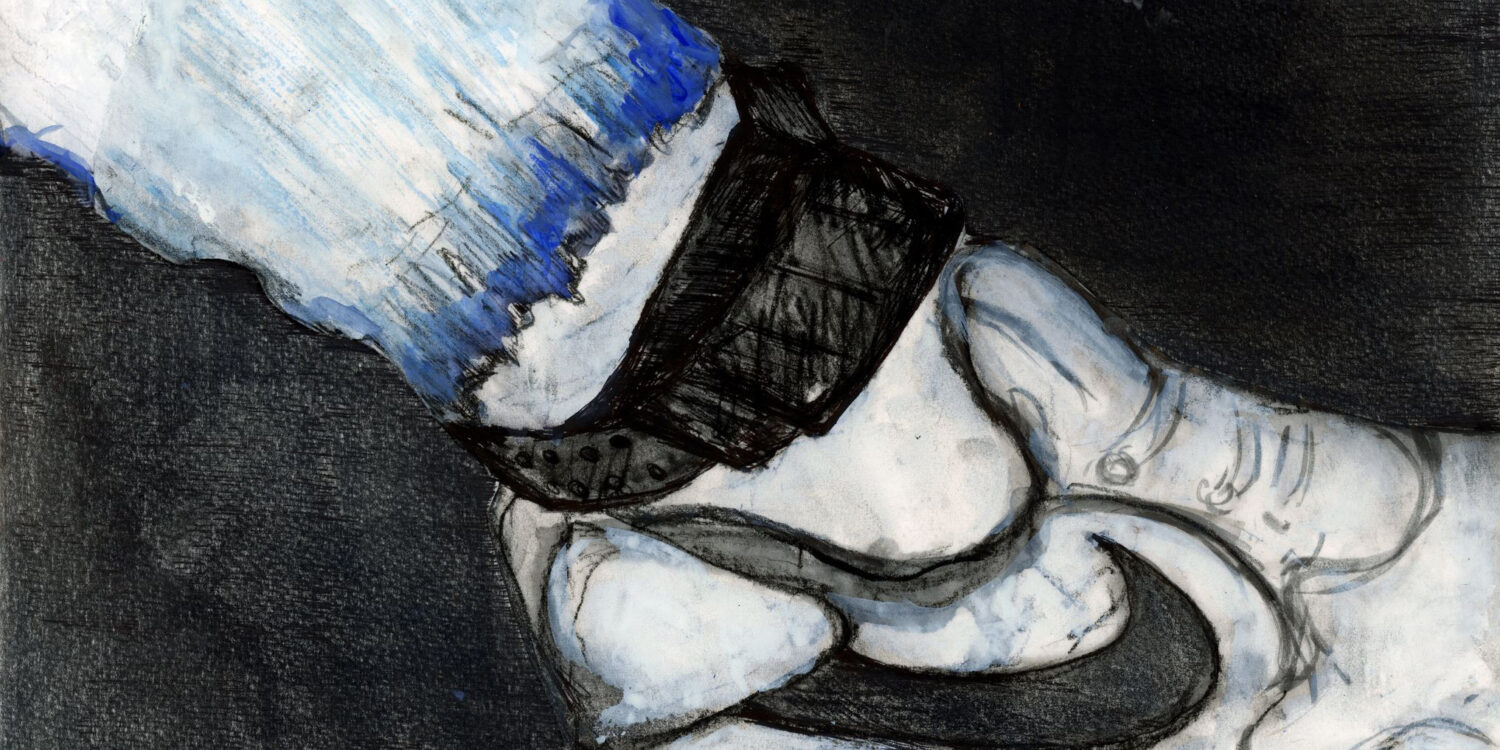

An electronic tag looks like a bulky grey band locked around a person’s ankle: it’s a surveillance device which tightly controls mobility through curfew restrictions and location monitoring. The tag is made of plastic, and can chafe against skin, causing “soreness, itching or burning,” according to a 2022 report by Medical Justice. However, removing a tag yourself is illegal: it has to be worn at all times in all places, including during sleep. First implemented as a punitive measure by the UK’s Justice Department in 1999, tags were mainly used to ensure compliance with probation conditions, and as a cheaper substitute for short prison sentences. However, since the 2004, 2014, and 2016 Immigration Acts, tags have been increasingly integrated into the apparatus of the Home Office. This overlapping of justice and immigration spheres has come to be known as ‘crimmigration’ – a useful term for describing the legal processes by which the State criminalises migrants. Indeed, since 2016, people seeking asylum can be tagged regardless of whether they have an actual criminal record. Successive Labour and Conservative governments defend this decision, arguing it’s administratively important to track people who would otherwise be a flight risk. Yet their supporting evidence remains weak: less than 0.56% of untagged people granted immigration bail abscond, according to a 2021 response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by Migrants Organise.

Unlike for British citizens, there is no legal limit to how long a person can be tagged on immigration bail. Asylum-seekers can wait weeks, months or even years to be free. In the meantime, their lives and their relationships to their surroundings are dictated by the tag. For two and a half years Ibz was fitted with a radio frequency tag, and he was never told when it would be removed. He pauses on the phone as he remembers: “Each year I used to think – how long until this tag comes off?”

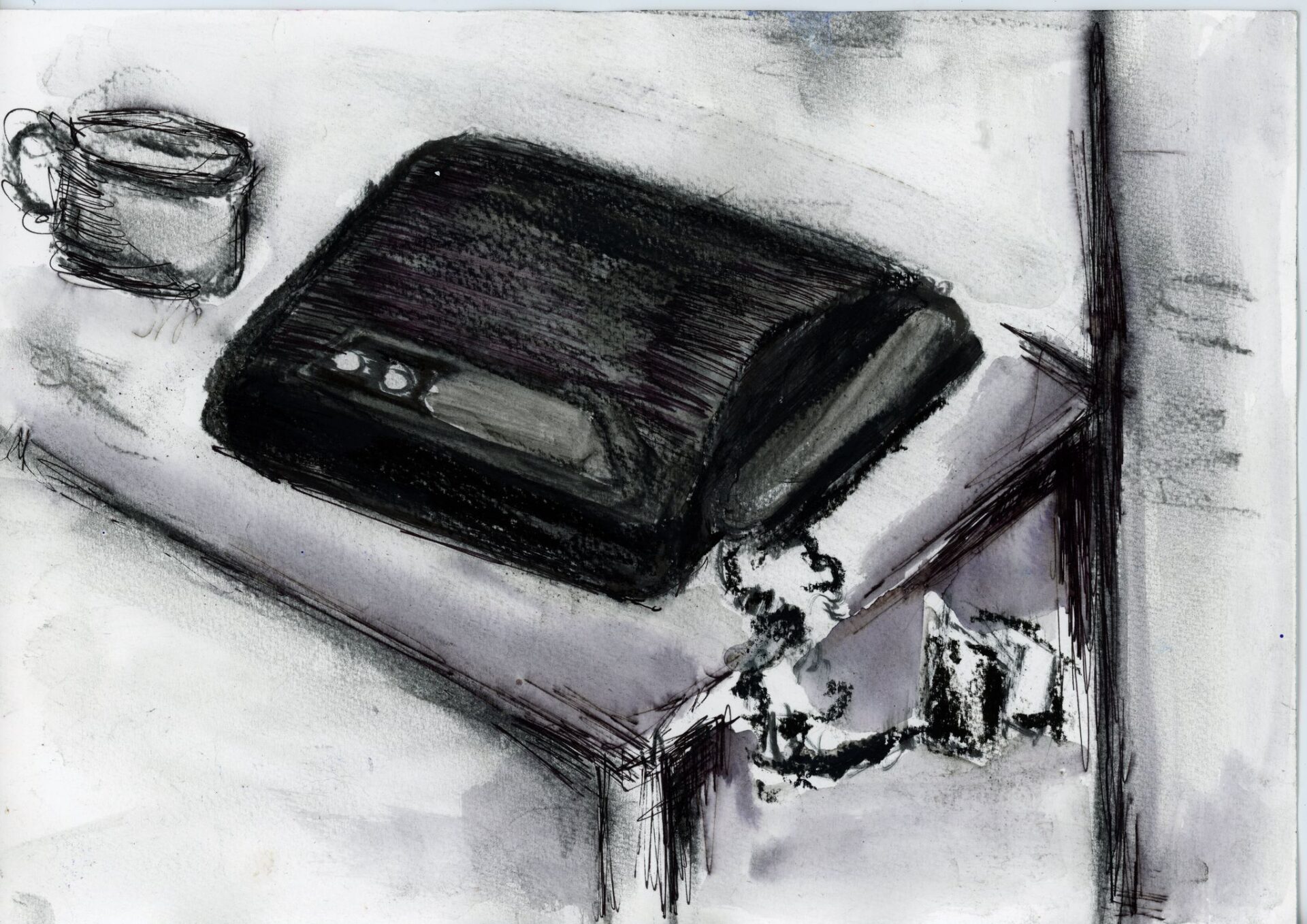

Radio-frequency tags enforce curfews, operating through a home monitoring unit installed in a living room or bedroom. The unit becomes the sharp point of a compass, tracing an invisible border around a home, policing its perimeter. If a person steps beyond the boundary between 11pm and 7am, their tag will alert an anonymous security contractor, who records a breach. This breach is passed onto the Home Office, potentially triggering arrest or deportation. Under the heading Tips to Help You Keep to Your Curfew, the Home Office’s Subject Handbook supplies a long list of Do’s:

- keep your tag on at all times

- stay at home during your curfew hours

- answer the phone when we call you

- make sure you have electricity available at your curfew address – if you have a pre-payment electricity meter, make sure you have enough coins or cards to keep the electricity on during your curfew hours

- give us written proof of any emergency within 48 hours of going out during your curfew hours

- make sure you have enough food etc. for each curfew period

- arrange your family needs and commitments around your curfew

How do you arrange your family needs and commitments around an immobile curfew, and what happens when the realities of everyday life contradict the rules of the state? During his second year on tag, Ibz had to urgently see his daughter who lived in a different city, but the distance was too far for him to travel there and back within a day. He decided to prioritise his daughter, and break his curfew conditions. The security contractor recorded his overnight stay as a breach, and Ibz was threatened with arrest. Although the state requires that “written proof of any emergency” has to be given “within 48 hours,” when you’re faced with a family crisis, there’s rarely enough time to navigate such bureaucracy. Especially when Home Office paperwork is so delayed that decisions which should be made in 24 hours, take an average of 59 days.

“The worst part about the curfew” Ibz tells me, “were my prayers.” In his untagged life Ibz used to pray regularly at his local mosque. It was a space that made him feel safe and held. But for two years the curfew prevented him from attending Ramadan prayers. “I broke the restrictions once, and went to my mosque anyway. But the whole time I was so worried that the Home Office would come and get me. It was a very bad experience. It was traumatising.”

For people displaced from their country of origin, moving to a new city means cultivating new place-attachments in the urban and social landscape. Attending prayers at a mosque (which over time switches from a mosque to my mosque) nurtures belonging through routine. But the tag impedes these freshly-formed connections. Ibz explains: “I couldn’t enjoy myself really in the city. If I wanted to go out with my friends after curfew hours, I was not allowed.” Restaurants, cinemas, friends’ houses, and evening prayers were all shut off to him. Instead, he stayed home each evening, stuck in a time-zone manufactured by the state, perpetually out of sync with the rhythms of Sunderland.

Even in non-curfew hours, the threshold of Ibz’s flat felt insurmountable. The endless routine of hiding his tag under socks and long trousers for fear the public might notice and cast judgement, having to cancel social plans because they coincided with curfew constraints, hurrying home in a panic before 11pm: it was emotionally and physically exhausting. Speaking quietly, Ibz says: “I didn’t even want to go out anymore. You get to that stage where you can’t go where you want to go – you just get used to being inside.” Although there was no lock keeping him inside, his front door took on the weight and shape of a cell door. It might as well have been barred.

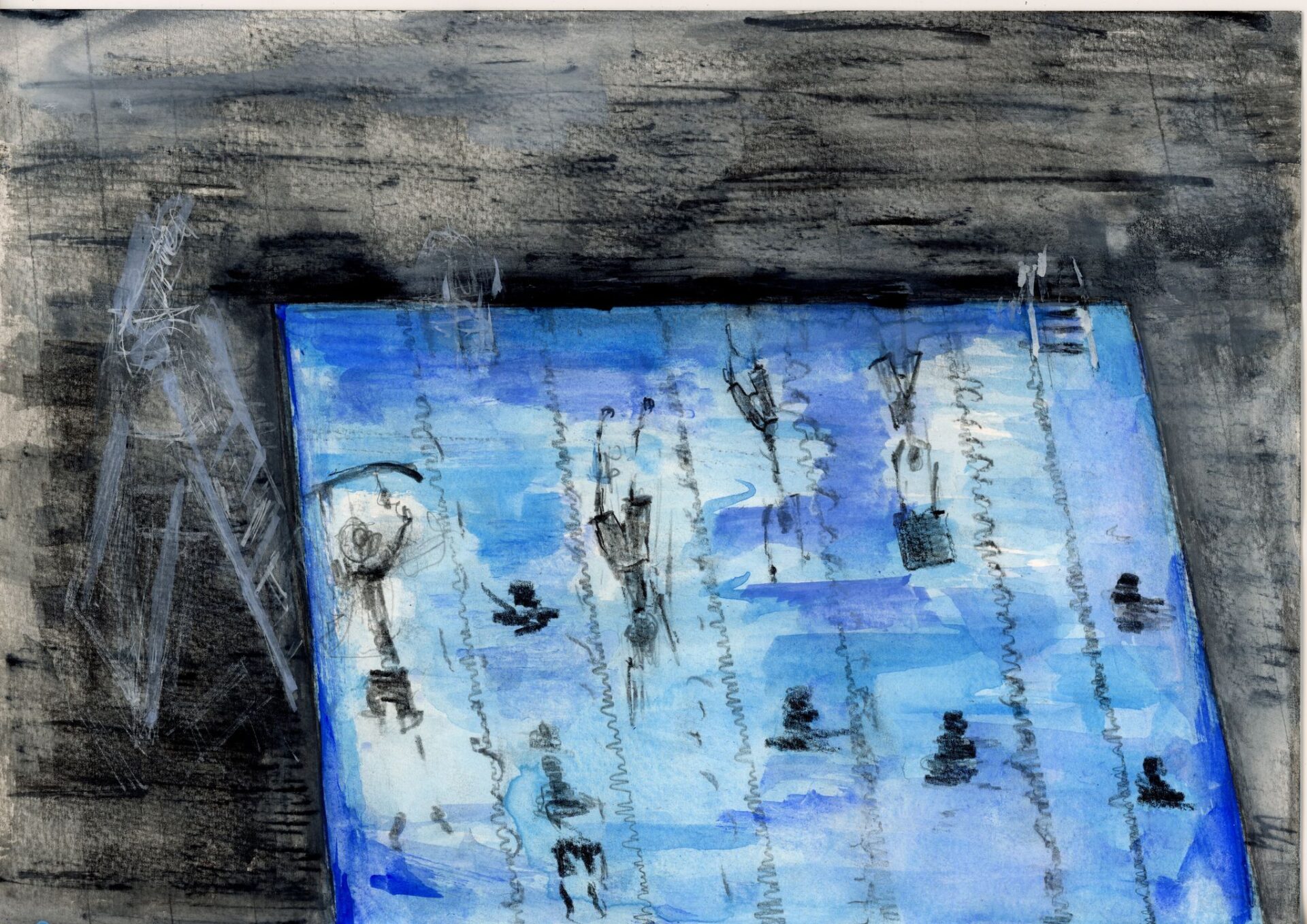

Still, being on tag is not the same as being in a physical prison. Whilst tagged, Ibz could eat dinner whenever he wanted, and walk from his bedroom into his kitchen or living room as he pleased. These relative freedoms are essential to the Home Office’s narrative setting administrative tagging apart from its punitive counterpart. However, because he wasn’t in a physical prison, Ibz was also completely alone. In a detention centre or prison, incarcerated people can and have united to resist state violence; they’ve engaged in collective hunger strikes and mass demonstrations, and have refused to leave their cells. By contrast, people on tag are almost entirely limited in their capability to come together and resist. They’re dispersed across the country, isolated within their homes and prevented from knowing each other. As Ibz explains to me: “The tag is such a different experience of prison to be honest. In prison, you’re locked up and people there are like the same as you; you have the same activities, eat the same food, you are in the same thing. There are people who are feeling it with you. When you are tagged, you are just by yourself and you can’t do anything with anyone anymore.” For Ibz, being on tag felt like the whole city was one big open-air prison, where he was the solitary inmate: he could walk down familiar streets and enter familiar shops, but still he would be on his own, navigating invisible walls.

In 2018, a novel tag which uses satellite-enabled location monitoring instead of radio frequency was launched by the Home Office. These newly-minted GPS tags only consist of the tag attached to a person’s ankle – they do not require a home monitoring unit – meaning they can track a person every minute of every day, wherever they are. The technology generates data that can be accessed by private security contractors, the police and the government. This level of surveillance is experienced as pervasive paranoia which can be difficult to recover from, even once the tag is removed. A report by the Public Law Project shows the impact of living on a GPS tag: people struggle to socialise, experiencing creeping dread that somebody is always watching them. Like Ibz, they avoid public places and social activities, anxious they’ll be judged for wearing the tag, and anxious about state surveillance. They feel the only option is to stay inside their homes and wait. They are stuck in place and time, indefinitely.

This social exclusion has a spatial counterpart: GPS tags can impose ‘exclusion zones’; places which a tagged person is not allowed to enter. When enforced by the Justice Department, zoning systems supposedly prevent people who have been incarcerated from repeating past behaviours, like domestic abuse or gang activity. In these instances, police and probation officers will use a person’s criminal record to create an individual map marked with no-go areas, and if the person on tag trespasses into these areas, they can be recalled back to prison. I spoke to an employee at a tech company that manufactures tags. Over video-call she describes, “There are so many postcodes that are exclusion zones − if you were to map them out, every street could be an exclusion zone for someone. I’m sure there are people who can’t even walk down my road.” Although people on tag are meant to be properly informed about their exclusion zones, it can be a struggle to stay within designated spaces. Public transport becomes nearly impossible, as the route a bus takes may cross the borders of an exclusion zone. As the tech employee explains, “There are particular roads [a person on GPS tag] might be allowed to drive along to get somewhere, but they aren’t allowed to go to any roads around it,” so the distance between one place and another becomes warped by the state. The tag co-opts the city into its carceral logic: without alterations to the built environment, urban space becomes segregated.

The same system of exclusion zones is used by the Home Office, extending the reach of the carceral into the city. However, these zones are not devised under the guise of keeping victims safe. In response to my FOIA request, the Home Office states: “Exclusion zones may be applied where there is an immigration purpose for doing so and will be specific to the full circumstances of an individual’s immigration case. It may prevent them breaching a condition of their immigration bail e.g. no right to take employment or study (a suspected place of work or education) or if there is reason to suspect that a person may be seeking to frustrate immigration control by temporarily exiting the UK to another part of the Common Travel Area and returning without presenting themselves to Border Force.”

The Home Office’s repetition of the term suspect suggests a mode of pre-emptive exclusion, barring people because they could pose a threat, not because they already do. This is compounded by the data mining of GPS tags, which compile intimate information 24/7, to be used as potential evidence. For example, the technology of the tag produces heat maps and synthesised reports of the “Top Five Locations” a migrant has visited that week, which the Home Office openly acknowledges using in the decision-making process regarding immigration claims. And as of March 2024, 44% of all GPS tags fitted in the UK are for immigration purposes: the shadow of the carceral state keeps lengthening.

In 2016, Ibz took his case to the Court of Appeal. The Judge ruled that the curfew imposed through the tag amounted to false imprisonment. Ibz was awarded £4,000 in damages and told his tag would finally be removed. He waited in anticipation, but nothing happened. A month after the court proceedings finished, he decided to cut the tag off himself.

One Sunday evening nearly a decade later, I ring to check in. We talk about that moment when his tag came off: “Of course, I felt relieved. My leg used to itch every night because of the tag, so it was good to finally sleep comfortably again. But not much else changed. I got too used to being behind doors.” I ask if he’s returned to his swimming pool. “Not really,”’ he says, “Sometimes I pray, I go to buy food, but I don’t swim or socialise anymore. I’m not that person anymore. I was on tag for too many years.”

Ibz is still going through the asylum process, still waiting for the right documents to live his life. He’s also still recovering from the impact of the tag. At the end of our phone call he lets out a gentle laugh: “I laugh so I don’t cry. Even after all this, you still have to choose to laugh, and choose to speak out.”

Not every person on tag is able to take their case to the courts, and not every case wins. In 2017, the year after Ibz’s electronic tag was finally removed, there were 298 people tagged as a condition of immigration bail in England and Wales. Today there are 4,446. In every leisure centre, mosque, cinema, restaurant, and bar there are people who should be there, but aren’t. Instead they’re waiting inside houses, hostels and flats to be released. The spatial violence of the tag comes down to a question of everyday mobility: who is allowed to move freely through the city, and who is not. Incarceration does not require walls or fences. Instead, mechanisms such as electronic tags participate in the broader state project of controlling particular bodies in space. To anyone who lives in a city or a neighbourhood: refuse the prison, refuse the border, refuse the electronic tag. Our streets are for everyone.

*The name Ibz is a pseudonym.