“I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe I would be mad enough to undertake it.”

– Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Piranesi’s words sum up his monumental sense of grandiosity and bravado and, unfortunately, that of many much less visionary architects. Yet this wild fantasy of conceiving a whole new universe can be realised in the virtual gamespace. Video games, bringing together the worlds of computation, narrative and experiential space in one medium, are becoming a new model of architectural representation. As such, gamespace can be used as a testing ground to design our future cities, a place where utopian thoughts are elaborated and experimented, an artificial arena where there are no rules except those set by the programmer.

That video games can play this role is arguably nothing new. City-building games, for instance, first emerged as a distinct genre in the early 1990s. These games are referred to as “simulations”: in the case of city-building games, the player simulates the role of architect and ruler of a city, designing its growth and managing its fictional communities. The genre was established in 1989 with SimCity and, unlike most video games at the time, it relied on the player’s sense of creativity and desire for control over aggressivity and competitiveness. City-building games such as SimCity and City Skylines seemingly prompted the player to build ‘the city of your dreams’.

More than anything else, however, city-building games serve as an object lesson in how not to use games to design our future cities. Mirroring the top-down principles currently regulating the built environment, the only type of city that these games allow you to create is a modernist, technocratic, grid-based, North American city. These city-building games function according to modern approaches to urban planning and design: totalising, single-handed and heavily reliant on zoning as an urbanistic tool. The question of the limits of growth is perpetually delayed and the natural environment is represented as nothing but a commodity, a pre-partitioned blank slate ready to be taken over. Unpicking the logic of game environments can lead us to understand how they challenge what we know about architecture and urbanism.

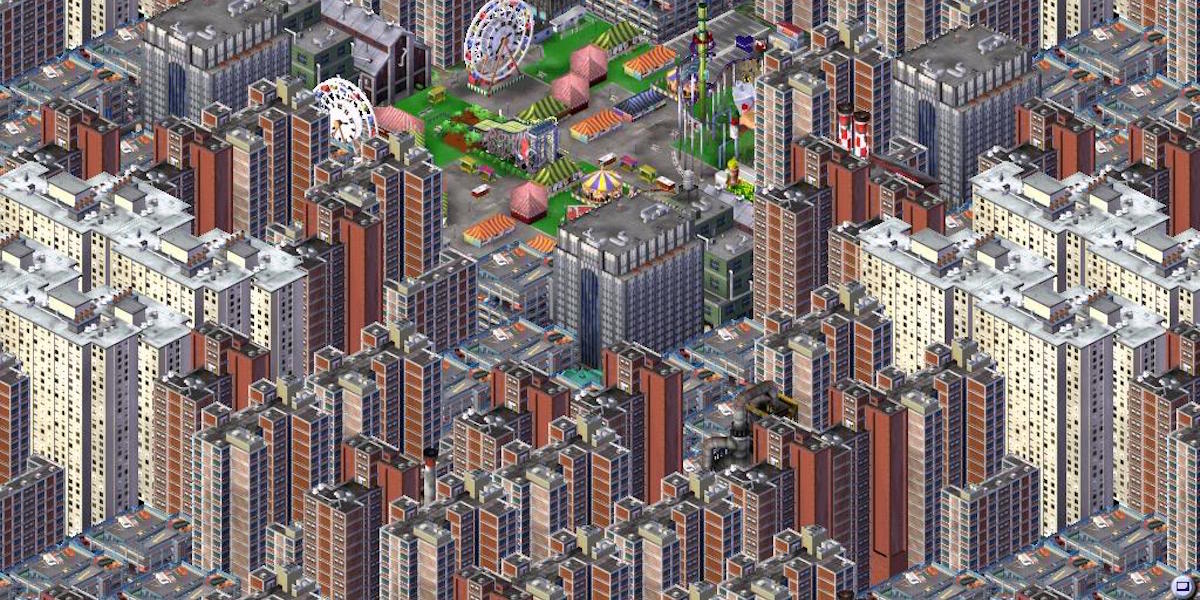

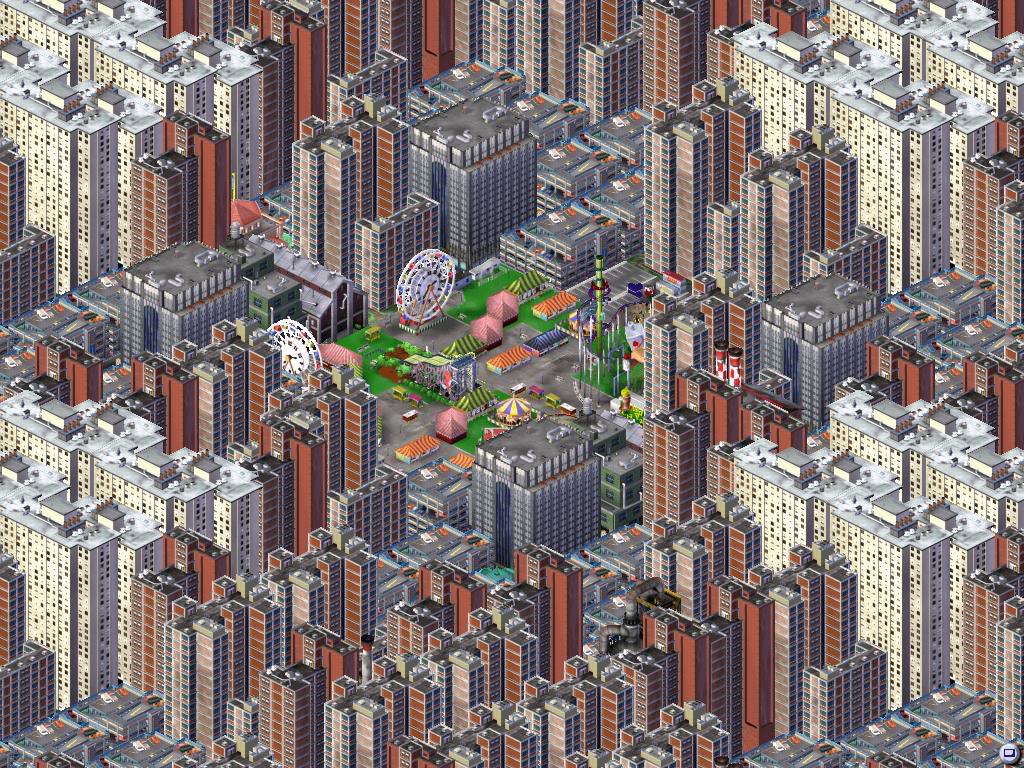

This is what happened in 2010, when 22-year-old architecture student Vincent Ocasla decoded the formula for completing SimCity 3000. After analysing the game’s algorithm, he figured out a modular structure for maximum efficiency: he created MagnaSanti, a self-sustaining city with a population of 6 million. With his project, Ocasla questioned the idea (upon which games such as SimCity seem to be based) that cities should be planned to boost the well-being of their inhabitants. In Ocasla’s words: “There are a lot of other problems in the city hidden under the illusion of order and greatness—suffocating air pollution, high unemployment, no fire stations, schools, or hospitals, a regimented lifestyle—this is the price that these sims pay for living in the city with the highest population.” That designing a hardcore totalitarian state can bring about the successful completion of SimCity might tell us something about the ideology of the makers of this game. MagnaSanti is just one formidable and dreadful instance of gamespace urbanism taking the game’s internal mechanics to its logical extreme.

But against the totalitarian tendencies of city-building games, and many other mainstream games in other genres, independent gaming has risen to become the site of critique for the all-too-real dynamics of gameworlds. Indeed, disrupting conventions (and their underlying assumptions) has become the core of radical gaming and contemporary art practice.

The following examples show how gamespace can become the stage for a social, political and ethical critique: from a nondescript city under the effect of gentrification, to a barren luxury estate and a set of playful and absurd buildings for London. These examples suggest that, rather than allowing architects to indulge Piranesi’s power-hungry ideal, games could work as a means of showing how dysfunctional reality really is. Beyond critique and virtual entertainment, the question they open up is whether games can be used as reliable systems to study and solve actual and theoretical conflicts. Given the state of cultural simulation in which we live, real-world problems may seem truly real only once they appear on a screen.

Molleindustria

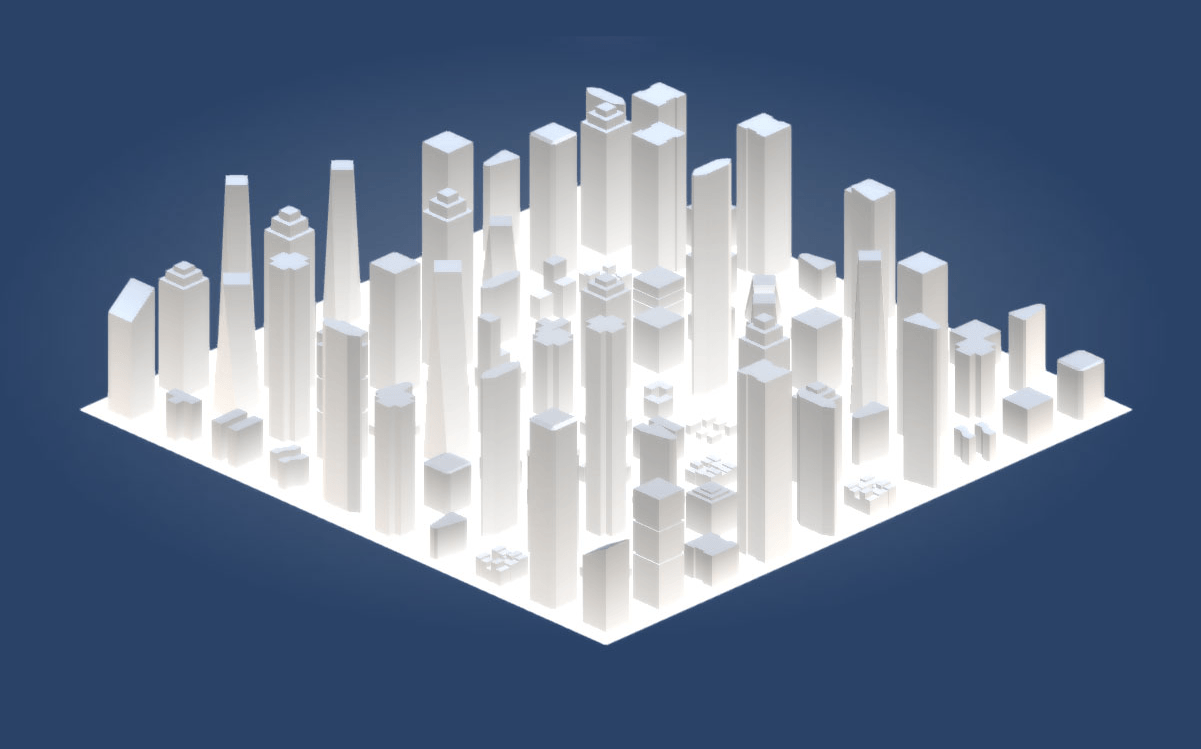

Paolo Pedercini teaches experimental game design and media production courses at Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Art in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His radical videogaming project Molleindustria has recently released Nova Alea. Set in an abstract city devoid of human presence, this game forces players into the role of real estate speculator. The strapline of Nova Alea is: ‘For its masters, the city was a matrix of financial abstraction’. In this simulation, everything can be reduced to quantity and numbers: dealing with a simple diagram of the economic and political forces at play in the development of a hyper-capitalistic city, the player realises the mechanics which are transforming many cities today.

Unreal Estate

Multimedia artist Lawrence Lek creates speculative worlds and site-specific simulations using gaming software such as Maya and Unity. Often based on real places, his series of nine utopian fictions, Bonus Levels, reflects the impact of the virtual on our perception of reality. In the ninth chapter of Bonus Levels, Unreal Estate (The Royal Academy is Yours) (2015), Lek imagines a future in which the Royal Academy of Arts in London – one of the nation’s most revered institutions – has been sold to a Chinese billionaire as a luxury private mansion. A first-person perspective tour through their new abode is accompanied by a voiceover, translated from the Russian edition of high-society Tatler magazine into Mandarin and subtitled in English. Set against the backdrop of the UK’s crisis in affordable housing, this multilingual narration comments on the complex relationship between ethnic identity, wealth, aspirational culture, especially as it affects property development. Unreal Estate is both a game of institutional critique and a surreal utopia where anyone can be a billionaire for fifteen minutes.

London Developers Toolkit

You+Pea is the architectural design practice of Sandra Youkhana and Luke Caspar Pearson. Together, they teach and investigate how architects can use video game technologies as an interactive means of understanding buildings and cities. London Developers Toolkit by You+Pea is a satirical app speaking of the frustration of being architects in London without much architectural agency amongst the many stakeholders. The project stemmed from the 2015 controversy about an advert by the developer Redrow, which enthusiastically depicted the aspirational luxury housing market in London. You+Pea decided to investigate this typology of residential developments and built a city game around it. The fictional buildings that constitute the game pieces represent critical elements of real buildings of London’s skyline. The game also criticises the process and the narrative behind contemporary architecture: players are being asked to produce inspirational ‘napkin sketches’ and visually evocative promotional material in order to capture potential investors. London Developers Toolkit is conceived as an interactive booth where visitors can play the game, produce their own skyscrapers, and use the app to print their own glossy posters. These printouts may then be put back out into the city, in an ironic form of protest: these fictional buildings, which will never be built, are just as absurd as some of those being built in reality.

This article was drafted following the lecture ‘Video games: Architectures of Ironic Computation’, given by Luke Caspar Pearson in July 2017 at the Asakusa art space in Tokyo, in conjunction with the exhibition 3Drifts.