This article is part of the FA special series Everywhere Walls, Borders, Prisons.

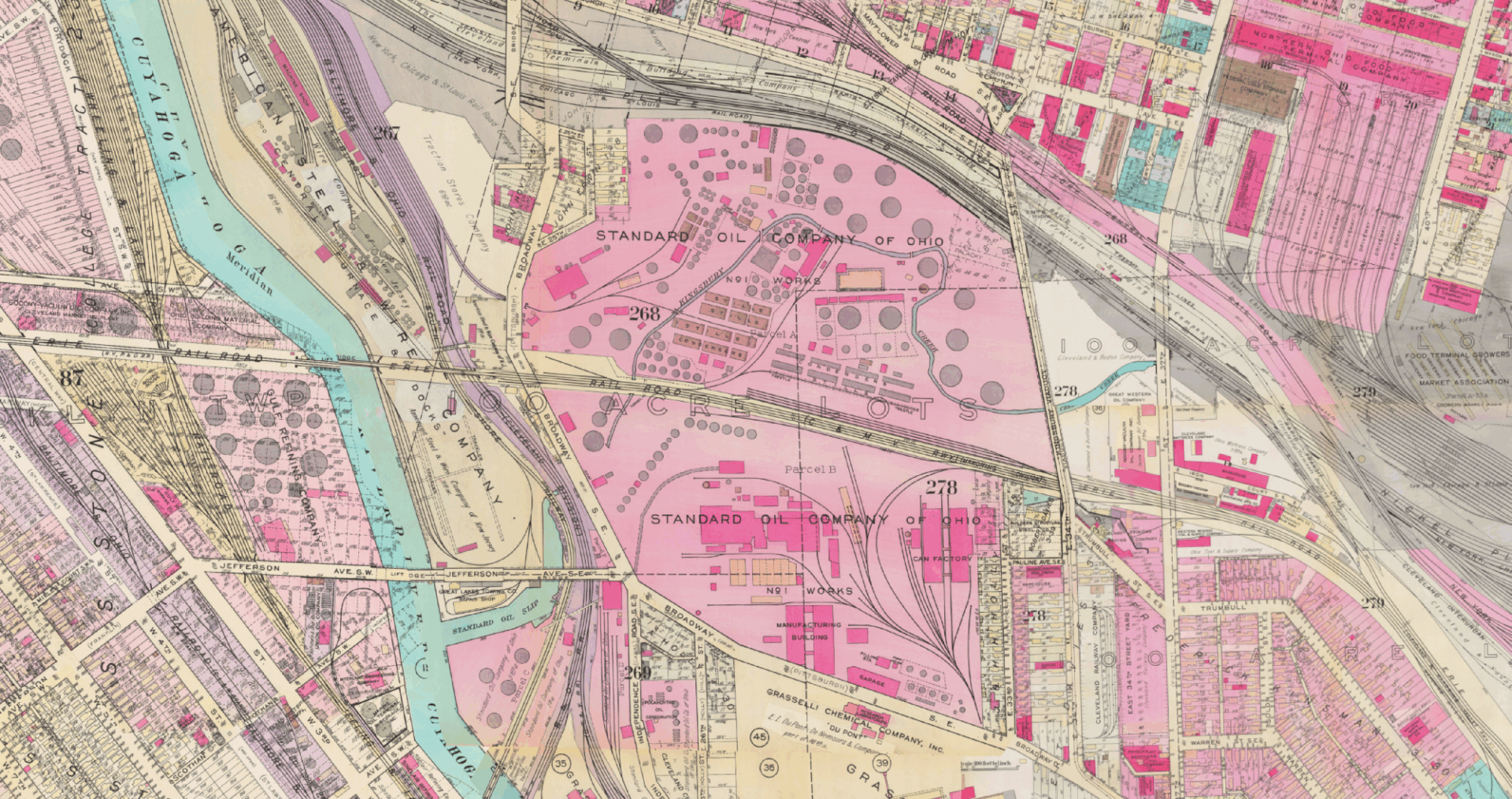

In 1982, the state of Ohio selected a site for a new state prison: 2700 Transport Road, Cuyahoga County. The 44-acre site was “ideal” for carceral development in many ways: it was large enough to accommodate all necessary programming, had a small existing building footprint that required little demolition, and was surrounded by a mix of industrial buildings, railroads, truck terminals and storage units which would avoid backlash usually present in residentially-adjacent areas. There was one catch: right before the land purchase was finalized, county property records surfaced showing that during the site’s prior use as an oil refinery, numerous hazardous chemicals had leached into the ground, including tetraethyl lead, asphalt hydrocarbons, kerosene acidic residues, and PCBs — highly toxic industrial compounds that have been proven to cause neurological development issues. Ultimately, state officials decided against the $4 million remediation plan and opted instead for a construction-ready site in a neighboring county.

Prisons were once the primary form of carceral development in the US, but this is no longer the case. Since the 2010s, the US has seen a steady decline in federal and state prison populations, represented by a 24.7% prison population reduction between 2011 and 2021. Although this might look like a dilution of the “mass” in “mass incarceration,” things are merely being rearranged. Over the past ten years, jail populations, particularly in rural areas, have surged by 27%. In the US, jails hold people who have not been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial, as well as those sentenced to a period of usually less than a year. In contrast, prisons hold people who have been convicted of a crime and sentenced to more than one year. While jails are locally funded and run, prisons are funded and run by either the state or federal government.

There is a silent jail boom occurring nationwide, and a large portion of these new jails are being constructed on toxic land. Since 2020, at least 23 jails have either been proposed or constructed on toxic sites in the Midwest. When thinking about rates of exposure to environmental toxins, it is critical to consider that jails see about 14 times more people coming through their doors than prisons. In 2022, around 469,000 people entered prison gates to be detained, whereas more than seven million entrances were recorded into jails. The number of people exposed to toxic environmental pollutants will increase dramatically as the jail becomes the predominant carceral typology to inhabit these toxic sites.

Jails are perceived as liminal spaces where arrested persons are held temporarily until either meeting bail – which few can afford – or facing trial, which can be delayed for years. The perception of jails as temporary holding spaces conveniently justifies county officials’ arguments for jail construction on toxic sites, the logic being that an arrested person’s exposure on a toxic site will not be significant given its temporary nature. Although the average stay in jail pre-trial is 26 days, there are many people who have been held for multiple years without being sentenced or convicted of a crime. In California, out of nearly 45,000 people held in jails pre-trial, there are at least 1,317 people who have been waiting for more than three years. Over 300 people have been waiting longer than five years. Arrest-hungry policing, bail affordability, and the lax nature of allowable sentencing periods combine to make these jails a particularly dangerous carceral mechanism, forcing a growing population to face elongated exposure periods in jails built on toxic sites.

Conditions that make a site ideal for carceral development change over time. In the 18th century, prisons replaced medieval forms of punishment such as public executions. At the time, it was common to find prisons near the urban core, where their proximity to centers of power made processing between trial and detention swift. As capital migrated spatially to enhance its capacities for expansion, urban real estate became more expensive and constrained. For capital’s migration to increase the value of certain spaces, it must devalue others; to expand untethered, it must shed workers whose labor power has been rendered unnecessary or “inefficient.” Whatever capital abandons – land and/or labor power – becomes devalued and made readily available for a new industry. The devaluing of land and people converge where populations deemed “surplus” are moved to areas also viewed as such.

US prisons constructed during the 1980s prison boom were predominantly built in rural areas. The consequences of capital’s devaluation of rural areas – industrial abandonment, rural precarity, and toxic environments – allowed for this land to be deemed surplus and become cheaply available for carceral development. Prison abolitionist and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore was the first to connect “surplus theory” to the prison construction boom of the 1980s. In her 2007 book, Golden Gulag, Gilmore asks why the Central Valley became the primary location for most of California’s prisons; specifically, “what already existing relationships make a town eligible for, or vulnerable to, prison siting in the first place?”

The Central Valley is a largely rural agricultural region, producing one-quarter of the nation’s food. However, since 1978 approximately 100,000 acres of irrigated land have been taken out of production each year due to interrelated forces of drought, debt, and development. This combination led to the emergence of surplus land – once-productive agricultural land that became economically stagnant and no longer “valuable.” As Gilmore vehemently points out, surplus land is not empty land. To support the Central Valley’s agricultural industry, lives were made and unmade around it. As these lands become surplus through capitalism’s creative destruction, unemployment levels skyrocket and the devalued built environments decay. To survive, these agriculture-monopoly-dominated rural communities and the land they inhabit find themselves in need of a new industry.

California’s new prison system made use of the Central Valley’s surplus land and seduced its surplus labor power with promises of employment and investment in the built environment. These promises, made by the California Department of Corrections (CDC), were soon broken. When pitching a new state prison in the city of Corcoran, the CDC advertised “benefits” including up to 900 temporary construction jobs and 800-1600 permanent prison management jobs. After the prison opened in 1988, fewer than 10% of the jobs were filled by Corcoran residents. The prison construction’s approval propelled Corcoran into a phase of anticipatory development. Based on the CDC’s projections of “higher than normal growth,” developers built new housing while the city borrowed $1.2 million to build new civic buildings and renovate the main thoroughfare. While the CDC expected 20% of new prison employees to move to Corcoran, only 7.5% of new arrivals were tied to the prison. The increase in housing stock was met by an increased vacancy rate, placing these new environments into a new cycle of decay.

Instead of job prospects and sustainable resource investment, Central Valley’s prisons put tens of thousands of incarcerated people at risk of dying from valley fever, an illness born of a microscopic fungus that thrives in dusty, dry swaths of land and that spreads by breathing in dust particles. Drought conditions, worsened by agriculture’s unregulated groundwater use, alongside soil disturbances caused by the massive prison construction projects, exacerbated the cases of valley fever. Cases have been steadily rising, with reported annual cases more than tripling from 2014 to 2023. While residents might have the option to leave the Central Valley, incarcerated persons do not. Seven out of eight Central Valley prisons are located in highly endemic areas. Central Valley’s prison boom demonstrates that for industrialized capitalism to thrive, some landscapes–and therefore some populations–must be designated disposable, surplus, and pollutable.

In his 2022 publication, Coal, Cages, Crisis, justice and critical prison studies scholar Judah Schept examines how the prison came to shape, and take shape in, Central Appalachia. After a vast and rapid land expropriation from Native American populations, Central Appalachia began its trajectory as a leader of the coal mining industry in the mid-18th century. By the 1980s, major coal, oil and gas companies owned 43 percent of the land in the region. Around this time, coal mining production began to decline due to cheaper energy alternatives such as natural gas from fracking, global reduction in coal demand, technological innovation, and resource depletion. Between 1983 and 2012, Kentucky lost 56% of its coal jobs – from 38 thousand employees to 17 thousand. In 2023, Kentucky employed around 5000 coal mining industry workers.

United States Penitentiary (USP) Big Sandy opened in 2003 in Martin County, Kentucky. The site on which USP Big Sandy was built had undergone mountaintop removal (MTR) under the Pocahontas holding company, which donated the property to the Bureau of Prisons (BoP) once all coal had been extracted. MTR, as its name implies, requires the destruction of a mountaintop to harvest coal from the seams that lie beneath it. Central Appalachia is not known for its flat and easily developable landscapes; as stated by an Eastern Kentucky local, “the good lord didn’t make level land here, coal companies did.” While MTR prepared the site for the development of USP Big Sandy in providing level land, it left behind toxic residues and unstable ground. The federal government paid over $40 million to remediate the site, making USP Big Sandy the most expensive federal prison ever built at the time at around $162 million.

The promises signaled by the new prison were extensive: from an increase in local employment to an increase in school populations, reinvigorated retail, support to social services, and investment in local infrastructure. Big Sandy Community and Technical College (BSCTC) criminal justice program graduated over 250 students in preparation for the employment opportunities to come with the opening of USP Big Sandy. However, no more than fifteen graduates landed a job at the new prison. Most of the promised jobs went to residents from outside counties. Instead, Martin County residents continue to face the public health effects wrought by the legacies of MTR, including an advanced form of black lung disease, water contamination by heavy metals, and cancerous growths. A 2018 U.S. News and World Report analyzed links between race, geography, and health outcomes, and found Martin County to be “the worst-performing county with an above-average share of white residents.”

The contingent relationship between industrial abandonment, rural precarity, carceral development, and toxic environments repeats itself across various sites: SCI Fayette, built in 2003 in La Belle, Pennsylvania, half a mile away from a coal ash dump; FCI Thomson, built in 2001 in Illinois, within a 50-mile radius of the Savanna Army Depot Superfund site, two coal plants, and two nuclear power plants; ADX Florence, built in 1994 in Colorado, located close to a former uranium mine and current Superfund site that has contaminated local water sources; Central Michigan Correctional Facility, built in 1990, and St. Louis Correctional Facility, built in 1999, both located one and a half miles from one of the most expensive Superfund sites in the Midwest, the former Velsicol Chemical Corporation plant site. The list goes on.

So why does this keep happening? One might argue that these toxic sites come at an unbeatable price, some even graciously donated for $1 to the BoP after all profitable resources have been extracted. That’s part of it, but given the significant cost of remediation to bring a contaminated site up to minimum standards for new residential construction (under which both prisons and jails fall) this “cheap land” theory does not hold up. How is it that pollutability and disposability are inscribed into certain landscapes and populations to this extent?

The beginnings of an answer might be found somewhere in between two interrelated spaces of thought: the constituent nature of environmental racism to the survival of racial capitalism, and the perceived “eventlessness” that results from the social abandonment of rural places. Regarding the former, I lean on geographer and ethnic studies scholar Laura Pulido who argues that the production of social difference is central to the creation and accumulation of value, and that uneven space is central to the unfolding of capitalism. It is not a failure of the market to produce sociospatial inequalities by race, class, or gender; rather, it is evidence of the routine functioning of capitalist economies. This is because, “Industry and manufacturing require sinks–places where pollution can be deposited. Sinks are typically land, air or water, but racially devalued bodies can function as “sinks.”” While one site profits and boasts “clean air” and “green” futures, the other absorbs the unwanted byproducts of industry – toxins as well as the racialized bodies who do not generate profit for capitalism’s see-saw.

This localized extraction goes largely unnoticed, given the areas in which it takes place and the populations who bear the consequences to their health and livelihood. Some crisis-laden events, such as last summer’s flash floods in Texas, rapidly capture the attention of the media, politicians, and researchers. The spectacular nature of these events and the immediate attention they draw force the state into action. In contrast, there are other forms of suffering that lack attention and action due to their less-immediately-catastrophic nature. These forms of suffering are not spectacular – they are what economist Elizabeth Povinelli calls “ordinary, chronic, and cruddy” and belong to the category of slow violence. They fall under radars of awareness and do not trigger state action. The threads that continue to weave together industrial abandonment, rural precarity, carceral development, and toxic environments have been and continue to be below the threshold of awareness.

While prisons might be shrinking away from toxic sites, jails are just beginning to spread and make use of these wastelands. Given the increased number of people that pass through jails, their perceived liminality, and the scant media and research attention given to jails compared to prisons, we must ask ourselves: What can we learn from the relationship between the prison boom and industrial organized abandonment, rural precarity and toxic environments? And why might these relationships be exponentially exacerbated through the expansion of the jail?

In 2022, 40 years after it was first considered as a site for carceral development, 2700 Transport Road in Cleveland was under consideration again. This time the proposed occupant was not another prison, but a $550 million jail. County officials argued that a new jail was necessary to mitigate the poor conditions of the existing downtown jail, which had opened in 1976. Again, many described the site as “ideal” given its size, small existing building footprint, and its industrial location. Ultimately and to the disappointment of many city officials, the Justice Center Executive Steering Committee narrowly voted down the proposal to purchase the 44 acres of land at Transport Road; the vote was 5-6, with one abstention. Again, environmental concerns were the reason for pulling out of the site. However, an environmental consultant had been hired prior to the vote to professionally evaluate the site. The consultant described the site as “not a scary property,” and clarified that building a jail on this toxic land would be an example of “normal urban development.” Without principled opposition at a scale that can match the machines that drive and normalize these carceral developments, it won’t be a matter of if but when we all become sinks for capitalism’s greed – perhaps we have already.