‘We are at the beginning of a mass extinction and all you can talk about is money and fairytales of eternal economic growth?’ So said Greta Thunberg in her outraged speech at the UN Climate Action Summit, which brought a new public awareness to the issue of limitless GDP growth. That same day, I was on my way to Norway, to visit the seventh edition of the Oslo Triennale, the Nordic region’s biggest architecture festival, curated for this 2019 edition by a team consisting of Matthew Dalziel, Phineas Harper, Cecilie Sachs Olsen and Maria Smith. The timing of Thunberg’s statement was convenient, since the subject of the edition, degrowth, offered a highly relevant inquiry into the limits to growth in economic, social and architectural terms.

The premise of the Triennale, titled Enough – The Architecture of Degrowth, is that environmental and social injustices are just two different facets of an untenable economic model. The link between the pursuit of economic growth and environmental issues has been apparent for some time now. It is a well known fact, for instance, that the 2008 recession resulted in a drop in carbon emissions. Likewise, economic growth in developed countries is achieved at the expense of people and ecosystems in developing countries, resulting in an ever more grotesque divide in which the 1% control nearly half of the world’s wealth.

It is remarkable to trace the history of degrowth and realise that it has been theorised since the early 1970s. The term itself was coined by French philosopher André Gorz in a public debate organized in Paris by the Club du Nouvel Observateur, at which he asked: “Is the earth’s balance, for which no-growth – or even degrowth – of material production is a necessary condition, compatible with the survival of the capitalist system?” That same year the Club of Rome released The Limits to Growth, the first study to outline the perils of limitless growth in a world with finite resources. Semantics have definitely contributed to the subject remaining relatively underappreciated since then – as Noam Chomsky has noted, the word “degrowth” itself frightens people: “it’s like saying you’re going to have to be poorer tomorrow than you are today, and it doesn’t mean that”. In reality degrowth is a collective project aimed at creating an alternative socio-ecological and political-economic order through the purposeful downscaling of affluent economies. Still, the vast majority of society doesn’t seem ready to acknowledge that infinite growth is untenable.

It helps to understand this mainstream aversion to growth limitation through the Kübler-Ross grief cycle, a model characterized by five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance (or DABDA). Currently, public opinion seems to be somewhere between denial and anger: “It’s not true! Why would we wilfully embrace degrowth? We need to keep on growing!”. Bargaining, the third stage, is underway among the most eco-conscious sections of society, whose members are committed to an individual reform of lifestyle in the hope that this can avoid the cause of grief: “I promise I will stop drinking my large latte in a disposable cup if this can prevent the system from falling apart”. According to the progression of the stages, depression should follow and subsequently a phase of testing new ideas until, finally, we arrive at acceptance.

The scientific validity of the Kübler-Ross model has never been proved, but it is a good instance of storytelling that can enable us to think the unthinkable, be it life after the death of a loved one or, indeed, life after the failure of our prevailing socio-economic structure. Being born in a capitalist economy in the West, imagining an alternative system seems almost impossible: as we know, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. Fredric Jameson’s famous quote is a self-fulfilling prophecy, unless a serious narrative effort is made towards imagining a systemic change. As claimed by Slavoj Žižek, the Left cannot limit itself simply to seeking new ways of realising the same dreams, it has to change the dream itself. The idea that capitalist economies can keep on growing just by switching to green energy and sustainable development is an illusion. But the full-scale transformation of economic, social and political relations that degrowth implies, requires us all to alter the way we live, work and move around. To achieve that transformation, though, we first need to be able to imagine it.

Introducing architectures conceived outside the logic of economic growth, the Oslo Architecture Triennale represented a necessary exercise in storytelling. Degrowth in architecture is not (only) the use of sustainable materials, and definitely not building harder, better, faster, greener – it is a fundamentally different approach to the built environment. Architectures of degrowth aim at a radical reform of habits through design, building according to very different collective needs, and even not building at all. As articulated by Pier Vittorio Aureli in his lecture “Less is Enough”, architecture should take up the role of integrating and making acceptable new conditions, which might be different from those we have become accustomed to perceive as normal or desirable.

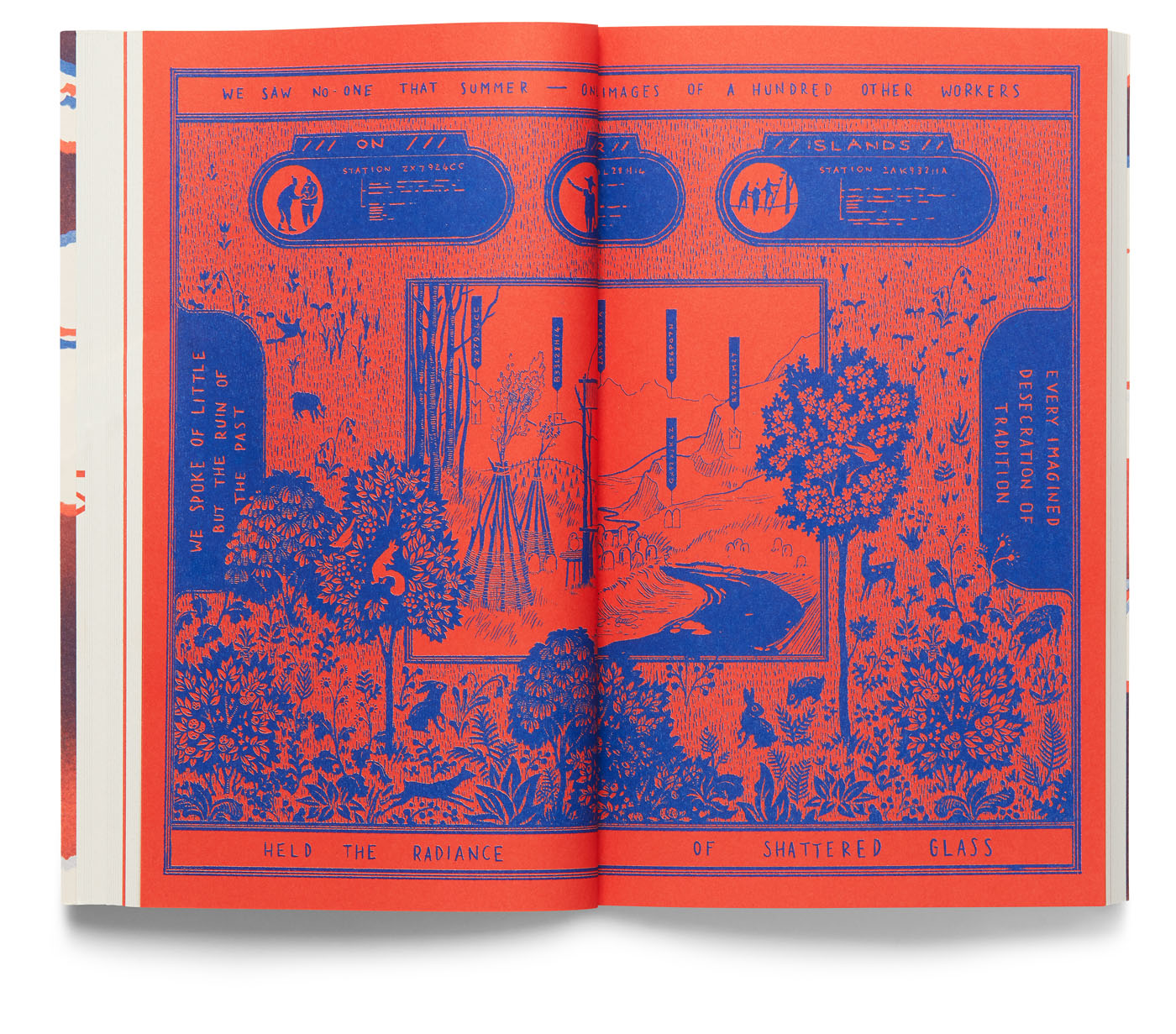

Enough – The Architecture of Degrowth shifts away from presenting degrowth purely as research, pursued through data and architectural projects, and instead attempts to express the concept through literature, games and performance. Since the present – and even more the future – of our current economic model is so unrealistic, the choice of putting together a book of science fiction instead of a catalogue seems entirely logical. The short story collection Gross Ideas – Tales of Tomorrow’s Architecture features stories set in near future scenarios. You Wanted This by Lev Bratishenko is, in my opinion, the most thought-provoking contribution: a dark nationality joke in which the representatives of different countries, who have acknowledged that climate crisis is irrevocable, convene to pitch solutions for mass extinction. The wide range of hi-tech, efficient and ecstatic options the representatives present can mitigate against universal suffering, and they manage to make the prospect of human extinction (especially if well designed) seem not so threatening when compared to the ecological and social horror we might have to go through if we stick to business as usual.

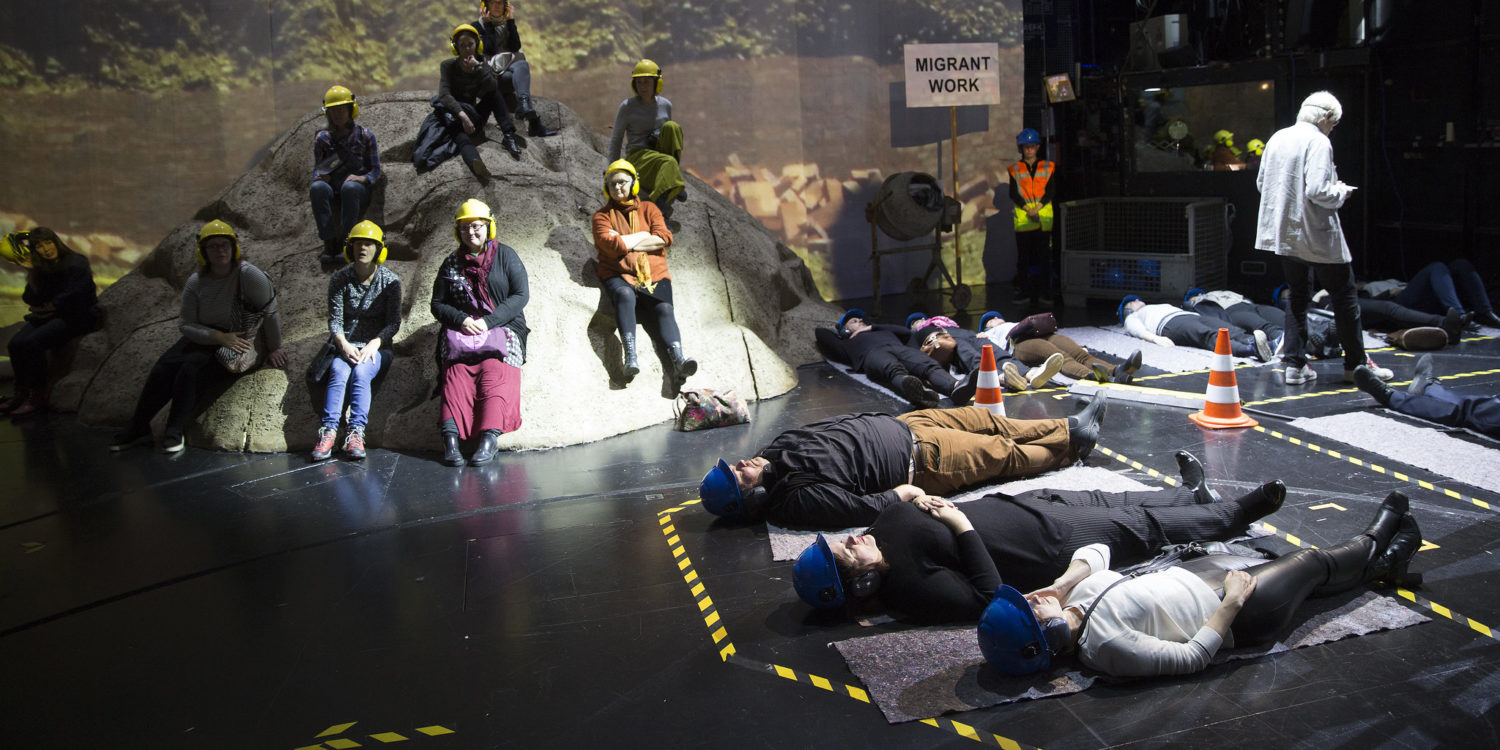

In the performance “Society Under Construction” theatre company Rimini Protokoll explored the paradoxes of capitalism, which are so theatrical that the script of the play wrote itself. Eight experts guided the audience in an embodied experience through the different stages of a major construction site. The perspectives of an investment consultant, an investigative journalist, a Romanian construction worker, the former smoke extraction engineer for Berlin’s BER airport, an attorney, an economist, an immigrant illegal worker, and a biologist – all played by actual professionals – were weaved together in a performance that showed the complexity of architecture’s relationship with capital. Ultimately revealing the structure of the microcosm around such grand scale projects, “Society Under Construction” uncovered how everything man-made can be unmade or made differently.

Also featured was “Bartetown” by Janette Kim with Jen Tai and Clare Hacko, a board game in which players conduct activities in a world without money, and instead based on an economy of favours and resource sharing. This bizarre version of Monopoly is also struck by sudden climatic phenomena. Every round a climate card is turned, which really changes everything. I was assigned the character of the developer, which brought about an ironic role-play of my worst instincts of ruthless speculation and greed. As I was trying to capitalize on my properties, I watched my fortune vanish like a character in some Nineteenth Century Russian novel and my estates flood as in Ballard’s Drowned World: an important degrowth lesson on how hard it can be to give up the game of capitalism when the stakes are so high, and a reminder of how important it is to foster social relationships in a catastrophic scenario.

Many contributions in the Triennale were stimulating, challenging both conventional ideas on buildings and the very format of the architecture exhibition. But a contradiction becomes apparent between a topic such as degrowth and an international event like Oslo Architecture Triennale. Flygskam is a Swedish term meaning ‘flight shame’ which sums up my feelings while travelling back and forth from Oslo by plane, like countless other people did, for the opening week. How to come to terms with the fact that cultural production and consumption largely contribute to the problem? Even though I managed to fall asleep during the flight, the dilemma was still there when I woke up. The curatorial team made several radical decisions gesturing at degrowth, such as using recycled materials for the exhibition design or deciding either to move via train or temporarily relocate to Norway, but they seem rather tokenistic in comparison with the complex machinery that such an event puts into motion. To summarize the problem in the words of Juliet Jacques ‘if you articulate an outsider critique well enough you stop being one’.

We shouldn’t be afraid of contradictions. Fear like that results in paranoid inaction. And yet, we need to acknowledge that the creative industry as we know it (indeed, all industry as we know it) cannot be reconciled with ecological justice. It is vital that we rethink creativity outside of the growth imperative, not as the privilege of a talented few but as an ingrained human characteristic. If we want to bring about meaningful alternatives to our current socio-economic order, this kind of creativity will be indispensable.