This article is part of the FA special series The Climate Changed.

The built environment is a testimony to the exploitation of earthen materials. Earth and its derivatives are the substance of most buildings, roads, landfills, parks, cemeteries, dams and dikes. Relocated masses of land shape our cities’ topographies and guarantee our energy resources (hydroelectric, for instance). Extractive projects in search of earthen supplies, such as mining and prospecting, also affect the land on a large scale. In architecture, earth is the feedstock matter that provides the materials of construction: sand, clay, gravel, mortar, cement, and brick.

Architecture and earth, and by consequence, the Earth, are intimately connected. But it appears that the further we have developed techniques using earth as matter, the further we have parted ourselves from it. After centuries of exploiting the earth, we’re left with a legacy of social inequality and human-provoked environmental disasters. Foregrounding the ways in which earth has been used to transform the environment shines a light on the social and historical implications of our relationship to earth. Moreover, narrating histories that depict the tortuous nature of this relationship may help us better deal with it in the future.

Nowadays, a significant amount of our soil is dirty, either filthied by harmful chemicals and particles in agricultural activities, or dirtied in the refinement and extraction processes of the building industry. In this sense, earth is an already-filthy material, with plastic particles and other artificial substances from manufacturing waste. Hélène Frichot’s 2019 Dirty Theory invites us to see dirt as both the substance that glues architecture together, such as clay, mortar, bricks, etc., but also the one causing its decay through its erosion, or the disintegration of buildings into dusty ruins. This dirt is not only material, but social as well.

In Northern Europe, the soil has been dirtied since at least the 14th century, when large-scale dredging operations began to shape the regional landscape. Low Country cities like Ghent and later, Antwerp, built systems of watermills and weirs to control floods, and later, to grant access to bigger ships at the ports. Today, the sand along the bottom of the Scheldt river is dredged to produce construction material and to displace land mass in the construction of dykes, beach embankments, ports, logistics infrastructure, and buildings.

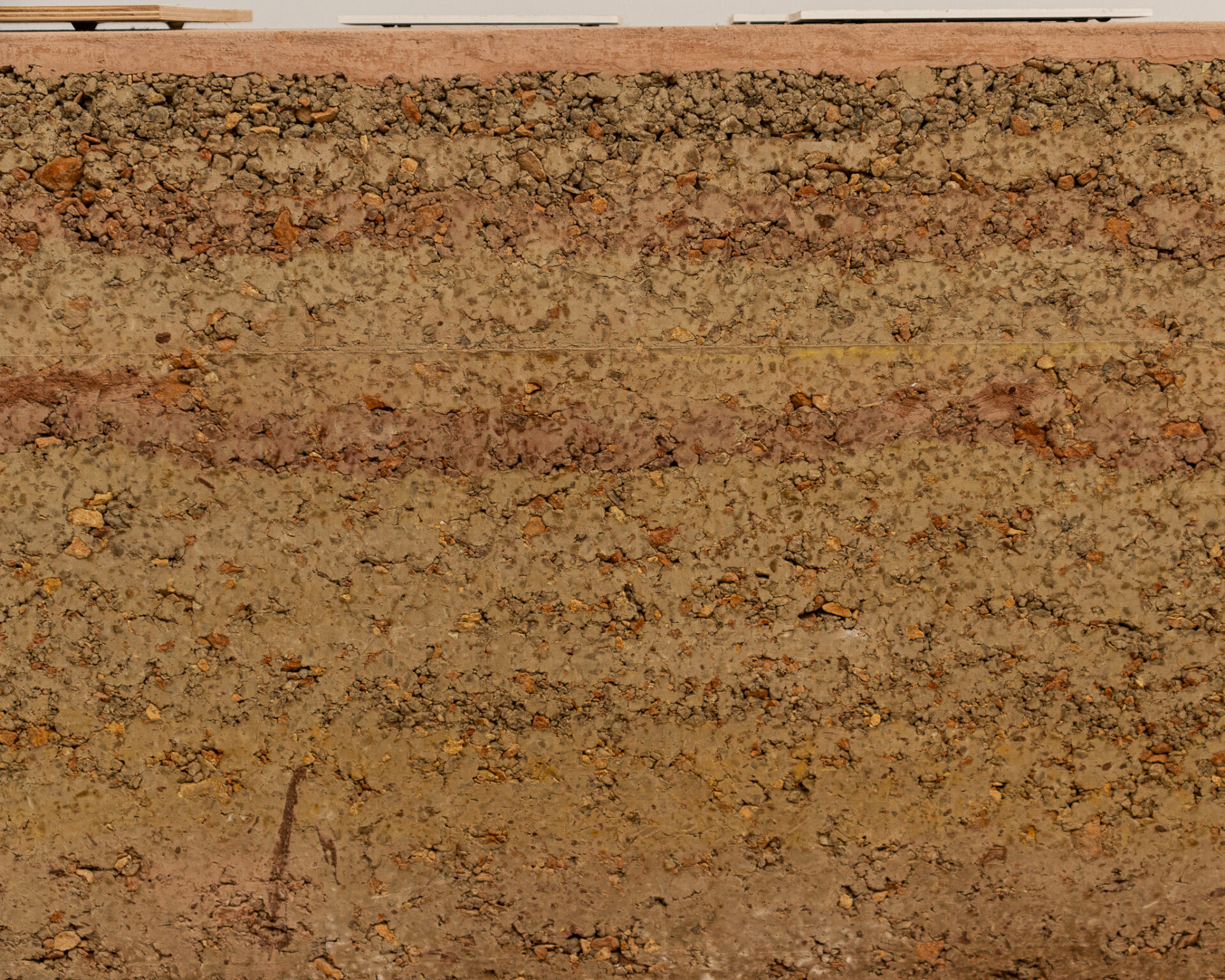

Manipulating the earth for flood control and building construction, and forming canals and polder systems gives the region its urban identity. Part of the earth taken from the riverbanks has been carefully separated into sand and gravel, and later aggregated with cement and water to create walls, structure and bricks – the building blocks of our buildings and cities.

Aerial view of the Roggenplaat sandbank, Netherlands

Luka Peternel / CC BY 2.0

According to the Vlaams Institute voor de Zee, 154m cubic metres of sand and silt have been dredged from the Scheldt’s basin since 1954 in the process of material extraction and to accommodate bigger ships. According to the North Sea Region IMMERSE/EU report, this dredging endangers flood control systems and the ecosystem, since it moves large quantities of sand and gravel, altering both the underwater topography and the ecological character of the river banks. Aggressively dredging the Scheldt has been threatening benthic life, impacting algae photosynthesis and propagating intense tidal waves that, paradoxically, lead to worse navigation conditions and more fragile protections against inundation.

Sand extraction has been decreasing, reaching an expected 1.1m cubic metres per year, according to impact studies made in 2010 by the Vlaams Institute voor de Zee. In 2023, following the case of the Scheldt, among other rivers, the EU called for the recognition of sand rights, promoting an understanding of sand as a non-renewable resource. In the call, the EU’s Directorate-General for Environment advocates for the reduction of sand consumption in the building industry through better regulation and taxation, and its substitution with alternative materials and methods.

The Scheldt case casts a light on our dependency on and abuse of earthen matter, which has become a contradictory dynamic embedded in our building culture. Earth is a non-renewable support for architecture and its aggressive exploitation is a threat to a more sustainable and resilient future for the building industry and the planet’s ecosystems.

Beyond the Scheldt, other century-old cases of exploitation leave behind a transformed landscape. Portuguese colonialism in Brazil was driven by pau-brasil (redwood) extractivism and sugar-cane plantations until the turn of the 18th century, when colonisers discovered precious metals in the silt of the Doce river basin in Minas Gerais. Since the late 1700s, mining and dredging riverbanks became the region’s main activity.

Exploring mines and silt for metals even gave the state its name: in Portuguese, Minas Gerais translates to ‘The General Mines’. Metal prospectors emptied Brazil’s inner mountains, and the relocation of dredged mud masses created a complex system of tailings dams. These mega-structures consist of an accumulation of overlapping embankments intended to retain the by-products of mining. Today, Minas Gerais’ steep geography has been transformed into a series of retention basin plateaus, a macro-architecture built through earth relocation. As result, Minas Gerais is a historically eroded land of around 600,000 km2, comparable to the size of Spain. Nowadays, mining and prospecting represents almost 10% of the country’s GDP, a valuable asset for exportation and economic sovereignty that keeps these activities running.

The Mariana Dam disaster sends a wave of mud into the Atlantic Ocean, 2015

Arnau Aregio / CC BY-SA 4.0

The two biggest industrial disasters of the country’s history unfolded as two of these tailings dams broke: the Mariana Dam in 2015, and the Brumadinho Dam in 2019. Waves of mud dirtied entire river basins with toxic waste. The dam breaks were brought about by multiple factors that evidenced the SAMARCO and VALE mining companies’ recklessness toward the environment.

In Mariana, 62m cubic metres of radioactive soil poured out from the retention basins into the Doce river and the Atlantic Ocean, causing almost 70 deaths. The unprecedented accident contaminated the water and covered the land with a crust that, when dry, prevents photosynthesis. Mud accumulated in the bottom of rivers, along coasts, and affected marine ecosystems, as registered by recent reports by IUNC in 2022. Two years later, iron micro-particles were still found in Abrolhos, an archipelago located 200km north of the Doce River Delta. In Brumadinho, 12m cubic metres of tailings spilled into the surrounding valley, causing 267 deaths. In a single catastrophic transformation, the mud swept away entire riverside communities, once more reshaping the landscape and the territory.

Bento Rodrigues District, Mariana, Minas Gerais, after the mudflow

Rogério Alves / CC by 2.0

Since then, measures have slowly been taken to repair the damage, to rebuild the villages, and to deal with the collective trauma, in both Brumadinho and Marina. Nonetheless, initiatives have been trying to reinterpret the “mudscape” and the trauma left in its wake as a form of heritage. This recently established understanding of heritage has opened the door to the protection of sites that have borne witness to humanity’s grief, such as the site of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, or the Cais do Valongo port, in Rio de Janeiro, where enslaved Africans were traded. Using the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, in a joint venture between the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and the National Institute for Art and Cultural Heritage (IPHAN), the communities of Brumadinho and Mariana were able to build new social relationships with the impacts of the exploitation of the earth in the region.

In Paracatu de Baixo and Bento Rodrigues, surviving buildings were considered for cultural heritage designation. In Paracatu de Baixo, the Santo Antônio Chapel made headlines during the Mariana disaster, as it was partially engulfed by the mud. The chapel, built in 1990 with little obvious aesthetic value, came to symbolize the daily life of the community before the disaster, and became a monument to the victims of the displaced earth. In 2016, the Mariana Government gave heritage designation to the integrity of the landscape and culture of Bento Rodrigues and Paracatu de Baixo, the Santo Antônio chapel included. The document, in an unprecedented gesture, stated its aim: “To serve as an example for future generations of how not to deal with mining,” and subsequently, land management.

From this moment on, inhabitants of Paracatu de Baixo still living in temporary shelters in Mariana have been proudly using the chapel as a symbol of resistance. Trauma marks left by earth’s exploitation and the resulting mudscape became the backdrop for newly-stablished relationships with land, memory and territory.

Besides causing irreversible environmental damage, projects that rely on aggressively processing earthen matter jeopardise the balance of future relationships with earth as a material source, and with ecosystems as a whole. Archaeologist David Van Reybrouck suggests that, by changing the environment, we are not only colonising territories, but the future of next generations too. Building and altering the land’s shape using earth has enabled the building industry to define earth as construction material. The impacts of centuries of exploitation call us to re-examine earth’s historically-constructed neutrality in order to better understand its dirtiness. Earthly matter is part of a complex arrangement that nurtures life and gives form to our already changed planet. Ultimately, to understand and undo the mess industries have made on earth, we need to understand natural resources – earth included – as parts of systems, as Indigenous Brazilian thinker Ailton Krenak advises.

Some contemporary architectural practices have been looking carefully toward earthen matter, learning from mudslides and the clay, sand, and rock which have been bound together into building materials. Traditional building techniques have been a social good, offering valuable lessons that can be implemented today.

The Negenoord Observation Tower by De Gouden Liniaal Architecten in Flanders exemplifies the use of local earthen material to reinterpret landscape and history. Two projects for the 2023 Venice Biennale also reimagine new approaches to our past with earth and land. In the installation Debris of History, Gloria Cabral, Sammy Baloji, and Cécile Fromont design modular panels inspired by indigenous patterns with reclaimed brick and materials that bridge Brazilian and Congolese colonial pasts and their resulting toxic landscapes. The colonial scar is also at the heart of the Brazilian Pavilion Terra by Gabriela de Mattos e Paulo Tavares, which uses rammed earth as an exhibition support, invoking Brazil’s Black and Indigenous architectural heritage.

These projects and practices suggest new interpretations for the historical dirtiness of earth, going beyond its abuse in colonialism, exploitation, and environmental degradation. Instead of only memorialising how earth has been left filthy by humanity, they attempt to highlight the relevance of non-hegemonic building cultures and traditional knowledge to contemporary design, putting into dialogue contradictions and the possibility of renewed relationships with earth.