This year’s short-lived Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City was an exciting prospect for many reasons. Focused on a long-neglected subject — and one of the first in-person exhibitions open to the public since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic — the show, curated by Mabel Wilson and Sean Anderson, featured work by the Black Reconstruction Collective (BRC), a group consisting of ten Black American architects who live and practice across the United States and beyond. This has been one of the few exhibitions in the United States focusing exclusively on Black architecture, and certainly the first in MoMA’s history.

Reconstructions had both a polemical and pedagogical character. On the one hand, it imagined a future for, and of, the Black community which today’s reality has brutally foreclosed. On the other hand, it viewed architecture not from the standpoint of whiteness, which has for centuries dominated architectural discourse, but from a Black perspective. Each participant presented a deep dive into a particular topic, be it historical, speculative, or both, with work expanding beyond the walls of the exhibition into websites, audio files and collections of various types, including some existing archives revealed through the architects’ research (see Mario Gooden’s “The Refusal of Space”) along with newly assembled compilations (see the spice stories of Germane Barnes’s project “A Spectrum of Blackness”).

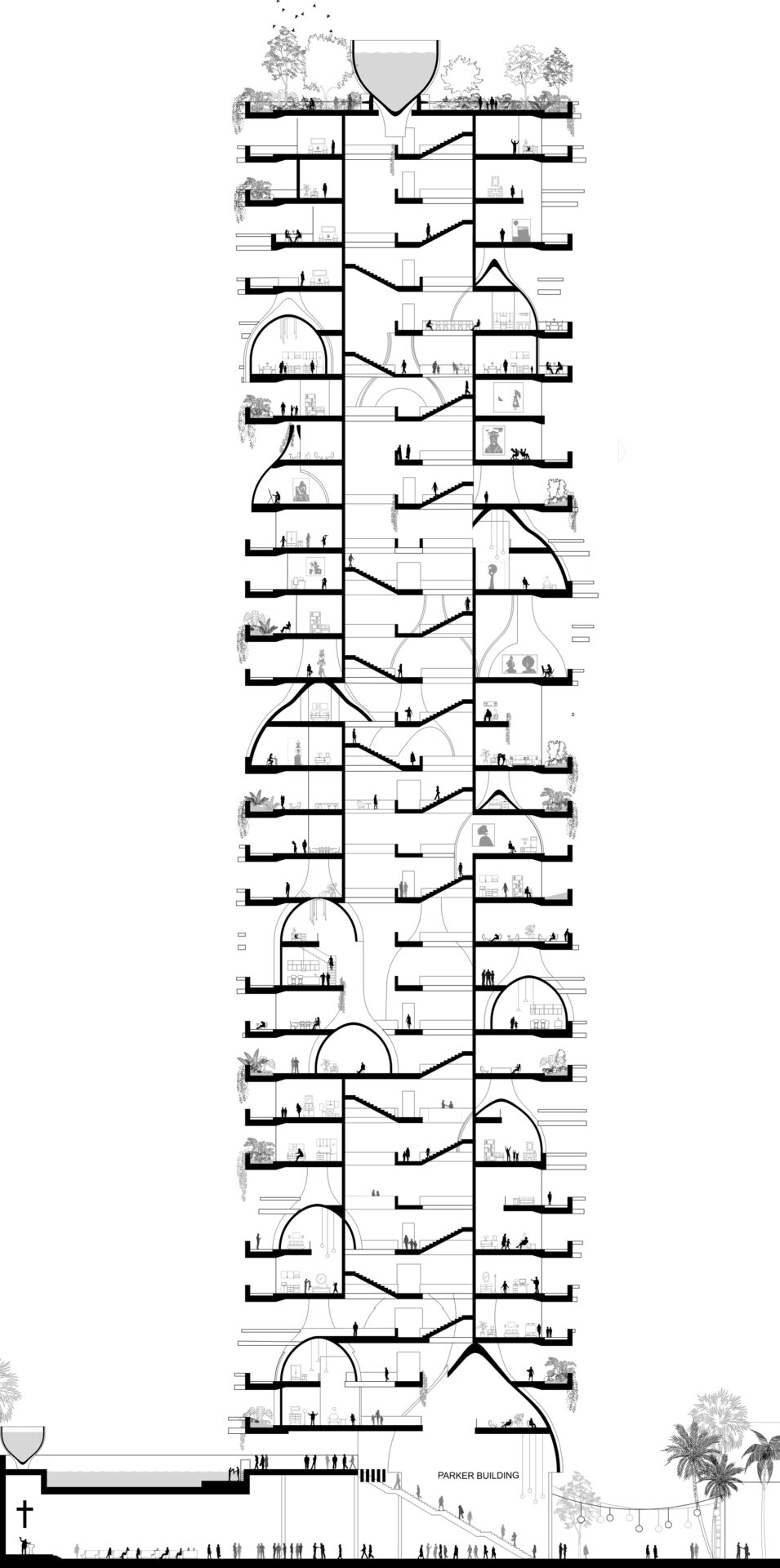

Nurturing an ongoing interest in the relation between design and political dissent through my own work, I found “Black Towers / Black Power” by architect Walter Hood to be one of Reconstructions’ most powerful projects. A professor of Landscape Architecture & Environmental Planning and Urban Design at Berkeley, and principal architect of Hood Design Studio, a landscape, urban design and public art practice based in Oakland, California, Hood has earned many accolades: he was a MacArthur fellow in 2019, and became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2021. Both the human-sized totemic models and large architectural drawings of “Black Towers / Black Power” immediately attracted my attention. Yet these materials are the result of not just a purely architectural imagination, but of a much deeper inquiry into culture and place. Hood’s research for this project encompasses the political Ten Point Program of the Black Panthers, whose specific claims for Black people’s self-sufficiency and liberation has a continuing currency fifty years since its inception. The project also honors the accomplishments of often-overlooked African-American industrial designers whose patented objects, such as folding chairs and pencil sharpeners, are omnipresent in our everyday life, yet not widely acknowledged in design histories. Hood magnified and extrapolated details from these objects into three-dimensional edifices taking the shape of fictional tower blocks: future domestic spaces characterized not only by aesthetic innovation but, more importantly, by programmatic boldness.

The ten towers envisioned for the San Pablo Avenue corridor in Oakland — the birthplace of the Black Panthers — are not simply proposed as schools or housing, but rather as centers for self-defense and civic pedagogy, and Black community service spaces, each embodying a point of the Panthers’ program. With this project, Hood’s aim is to continue W. E. B. DuBois’ commitment to “the right of black folk to love and enjoy,” rather than simply contribute to survival of Black lives within the continuing discriminating socioeconomic conditions of contemporary America. Acknowledging that it has been hard for Black and brown people to imagine a future for themselves in this country, Hood aspires to extend the power of architecture as a tool for social and political transformation in the Black community’s hands.

In the spring of 2021, I met with Walter Hood to discuss the origins of his architectural proposition, and the contribution of his architecture to the work of social movements. Around the same time, the Dark Matter University had begun an ultimately unsuccessful petition to extend Reconstructions longer than its original 13-week duration, which would have allowed for larger visibility during lingering pandemic conditions. With its refusal to extend the exhibition (which was promptly, and controversially, replaced by show about car culture), MoMA revealed a lack of commitment to the Black Reconstruction Collective’s calls to hold the nation and its institutions accountable for their culpability in systemic racism and its impacts on the built environment.

Jilly Traganou: Thank you so much for accepting my invitation to talk about your participation in the Reconstructions exhibition. I was intrigued by your “Black Towers/Black Power” project, partly because of my ongoing research on the relation between design and social movements, and I was particularly interested to hear that you have been inspired by the Black Panthers. What do you bring to the work of social movements as an architect?

Walter Hood: What has become very evident, particularly in the last year, is that it’s really hard for Black people to see themselves in the future, and that when you look at the processes at play — whether through community design or through a more democratic way of thinking about design — what you see in our African-American communities is that we somewhat design our future out because we’re stuck in this more paternalistic way of looking at ourselves, of how others have looked at us. And so to me the question is: How can we get out of that, and how can I as an architect think about what my community will look like in 20 years?

When I look back 50 years ago, and think about what people were saying then, I realized that we never got there. It still looks like it was 50 years ago. So in a way, I think our work is to try to get people to see themselves in the future in a different way. I was inspired by the Black Panthers and the things they were saying 50 years ago because we still need to do these things today. And I was also taken by our inability to see ourselves in high rises, and the inability of the government and other agencies to think about us in a certain way. You know, Pruitt-Igoe, Cabrini-Green — all of these social housing projects which took us out of the future, to a certain degree.

JT: In places like New York, where I’m based, there is a certain association between low-income communities and high-rise brutalist social housing which, for many, is quite stigmatized. And at the same time you have luxury towers, condos or rentals, but also high rise projects from the mid-20th century, like the one where I live in the Bronx, that are managed in different ways, and where you can see that life in high rise buildings can have positive aspects as well — not only the views, but also the formation of cooperatives that operate on a different logic from private investment.

WH: So it’s funny you say that. When I got out of undergraduate school, I moved to Washington DC from North Carolina. And I lived in a tower, on the 25th floor, and it was amazing. But today Black people are faced with our inability to see ourselves in a diversity of settings. We’re always treated as this kind of monolithic group. I read a review by someone who wrote about the show, suggesting that Walter Hood just designed some towers. But they didn’t get the idea that it’s hard for people to see us in a tower in a positive way. And that to me is the bigger issue.

JT: I was very intrigued by these towers, both by their presence as models in the exhibition space, and by their names — furnace, folding chair, pencil sharpener — which, as I understood, derive from patented objects by African-American designers.

WH: When I found the patents for what I call “mundane machines”, I understood that they were inventions created by workers. I think it was during the latter part of the Industrial Revolution when the machines became much easier to make. It’s really at that moment when people doing manual labor were able to participate in the production of machines. For example, someone sweeping the floor and then using a piece of paper to pick up the dirt, and thinking that there’s got to be a better way to do this. I can see laborers thinking “there’s got to be an easier way”. And so these inventions come out.

JT: It’s very interesting because this creates a shift from being a laborer to becoming a designer. And also we see the means of production being produced by different hands, and potentially creating different social dynamics. Back to your work: How do the patented objects become towers, and how do the towers connect with the Black Panthers’ Ten Point Program on freedom, employment, housing, health-care, anti-police brutality, and so on?

WH: If you look at the drawings on the wall of the exhibition, these are model prints inspired by the patents, which I conceptualized in a kind of a tectonic way. I looked at the dustpan or the pencil sharpener, and I thought: Could there be a way to, again, transfer that kind of knowledge or validate that knowledge through architecture? Then I created these three-dimensional blocks, and started going back and forth between the blocks and the plans, trying to find the gestalt of each machine. And all of a sudden, the tectonics emerged. and I started to imagine them almost like machines that you can live in. How can the core of the pencil sharpener become the core of a building?

After I arrived at the idea of the tower, I started thinking about the Panthers as a means to create a different programmatic way of thinking about architecture. One tower became about housing, another about police brutality, another about education. And one of the things that I found along San Pablo Avenue in Oakland, where the buildings are located, is that most of the nonprofits there are faith-based. If you noticed, at the base of a lot of the towers, there is a church. Those are the preexisting conditions. The idea I’m suggesting is that the nonprofits, which basically use the metrics of poverty to build their social housing and to stay in this neighborhood, can’t see themselves building something at a higher density — something that’s much more diverse and much more projected into the future. So each one of the towers became really these mixed-use things. Instead of just having senior housing, you add art studios, you add all of these other things that reinforce the program, and you get these almost separate little cities.

I also introduced an element of fiction. The idea was that, literally, the Black people in Oakland are the only ones who could see the towers, and they would be the only ones who could go and experience these different vertical landscapes.

JT: I wonder about this method of futurity. While it is more traditionally associated with literary fiction — and I can think of writers like Octavia Butler, Samuel Delany and other Afrofuturists — it is interesting to see it appearing in architecture and design. And at the same time, we have different social movements thinking about the future and trying to mobilize imagination in a collective way. While designing these towers, were you connected in your process of futurity with people from other communities and practices, besides those of architecture?

WH: I was actually working with a nonprofit in the beginning, which was the inspiration for this project. I was working with their economic team. The area where my project is located in Oakland was red-lined in the 1940s and, in my opinion, still is a red-lined area. So, if you look at that entire area, there’s nothing over five stories. Developers look at that landscape and go “I can’t build anything here because I won’t get my money.” So everything here is subsidized; but you literally go one block further and they’re building 28-story tall buildings. And so I was asking: Well, why are we doing this? You don’t see a red line, but the red line is still here. We do see the proliferation of social projects for elderly people, liquor stores, all of those things that go along. And so talking with the nonprofit, I decided that it is important to preserve some of these things as a preexisting condition worth keeping, such as the churches and faith-based institutions. But coming back to your question about the future, and this kind of projection that’s not only done by architects, I think it can be really hard for people who have lived in a certain way to imagine it. In these landscapes there’s no incentive. And in my project what I’m trying to do is to incentivize imagination. So the fiction had to bring this other way of thinking, because if you follow the typical way, you end up in the same place.

JT: I was looking at your office’s website and I saw a lot of landscape, public space, and art projects, and maybe I missed it, but I didn’t see what the typical architectural scale is in your work. Is this absence of architecture intentional in your practice, and does this MoMA exhibition signal a new era in your work?

WH: It’s funny you say that because, you know, I am trained as an architect, landscape architect, artist and urbanist, but I don’t practice architecture. When Mabel Wilson invited me to be a part of this exhibition, I was thinking a lot about what I do. And the idea of the towers suggests that there are some things landscape can do, and there are some things landscape can’t do. And so at first, I was going to do a project that would be called “low income landscapes.” And I was going to make a landscape that was just low income. But then it dawned on me that there was no future in that, and that’s where the tower idea came from.

JT: That was a great leap! From a low-income landscape to an architecture of high-rises. And a new type of wealth: perhaps social wealth generated through a Black Panthers-inspired programming.

WH: I was reading the Black Skyscraper by Adrienne Brown at that time. It’s really a wonderful book. And there’s a part in there where she talks about DuBois. DuBois wrote fiction, which I didn’t know about beforehand. And he was doing a lot of work in Philadelphia, looking at issues relating to race and poverty. But he was frustrated that maybe his work wasn’t being taken seriously, and so he used fiction as a way to project the future. One of the stories he writes is set at the beginning of the 20th Century in New York, when the world seems to come to an end. On the top of a high rise building are a black man and a white woman, and they’re the only two people left. They look at each other and there’s a moment where they really acknowledge each other as people, and then, all of a sudden, her husband appears. I was inspired by that kind of projection, and so in thinking about that, fiction became really, really important.

JT: Very interesting! I will look for this story. I am fascinated by Michel de Certeau’s writings about the panoramic view of the city from the World Trade Center, in contrast to viewing the city from below. But now that you are saying this, I think it’s interesting to juxtapose these two visions of the city from the tower. On the one hand the contrast between the view from above and the view from below (or the view of the planner versus the gaze of the anthropologist) that de Certeau is discussing, and on the other, a different kind of juxtaposition, between the past and the future, that emerges when looking from the tower from a perspective of social change like the one by DuBois. And perhaps the idea that we also need the tower for social change as a place of the imagination, and that the work would not happen only on the ground.

WH: It’s interesting that, for Adrienne Brown, when you’re in the tower looking down you don’t see race. She makes that comparison with the tenements, where when you went through the landscape, you could see race. But somehow the tower changes all of that, and for me that was very provocative.

JT: Can you talk to me about MoMA as an institutional framework for this work? I suppose it provided resources, visibility, maybe even the idea of doing this collective exhibition. Is there anything that would have been done differently if it was not for MoMA, or with MoMA?

WH: MoMA is an institution that, for better or worse, people look to, and in the last year there’s been a lot of critique of a lot of institutions across the country. But if the show had been at, let’s say, the New Museum, or another place, I don’t think it would have had the same impact because by being in MoMA, it has an impact on the history of the present moment. It’s a critique of this history, and I think that we have to begin to be in these institutions and challenge these institutions, particularly the ones that have been the home to a lot of these dominant ideas in this country, particularly modernism. My fear is that everyone wants to go back to normal, and I’m very hesitant, because people might easily say, “we did the Black show, so we could move on now”, right? This is how things are in America.

JT: Was this show planned before the pandemic?

WH: It was supposed to open last summer, so it had very little to do with the pandemic, and had more to do with the work of Mabel Wilson looking through the archives and seeing this deficit. Where you have people of color like Max Bond and others who have been heralded but are not present in the canon at all.

JT: My last question is about the Black Reconstruction Collective, which is the group formed by the architects who participated in the exhibition. I wonder about the process of your work together, and if you see a future in this collective work.

WH: The BRC was established to create this kind of ownership of the work, for one, but also during the time we were working, we weren’t collaborating and everybody was doing their work on their own. So BRC became a means to collaborate, not on the specific work, but collectively as a group in the future. And to also create mentorships and other resources for young designers. In a way, BRC is creating this new kind of cultural ground for young and older people of color, and gives them a place. Before that, there was no place where that could happen, and so these ten very diverse voices provide that setting.

JT: It’s interesting to see the parallel between the collectivity in the work of social movements and collectivity in the work of architects and designers, beyond what is accomplished by the architectural office.

WH: It gets back to my earlier point. As Black designers or artists, we’re diverse, we have diverse interests, in diverse voices. Someone looks at my portfolio and goes, well “Why is he making a building”? Why can’t I make a building? Right? What I resisted in my entire career is being pigeonholed in a certain way. It’s those kinds of things that BRC is addressing. The BRC might allow us to stretch and become much more.

Top image courtesy of Hood Design Studio.