Amsterdam is rolling out the red carpet. A sanitising red-carpet. Baron Haussmann is also lending a hand, his legacy of reshaping 19th century Paris celebrated in the form of a luxury department store that shares his name. How does Paris’ 19th century redevelopment compare to current changes in Amsterdam?

Red carpet treatment

Amsterdam’s city council wants the city’s centre to be more presentable to tourists and other visitors. A key focus is on a central corridor running south from Central Station, an area which has long been characterised by small businesses, souvenir and coffee shops, neon signs and greasy cuisine, as well as a series of ‘ugly buildings’. Such associations will soon be history, because the city is being cleansed of all those unwanted elements, to make way for luxury shops, fancy hotels and questionable global fashion brands.

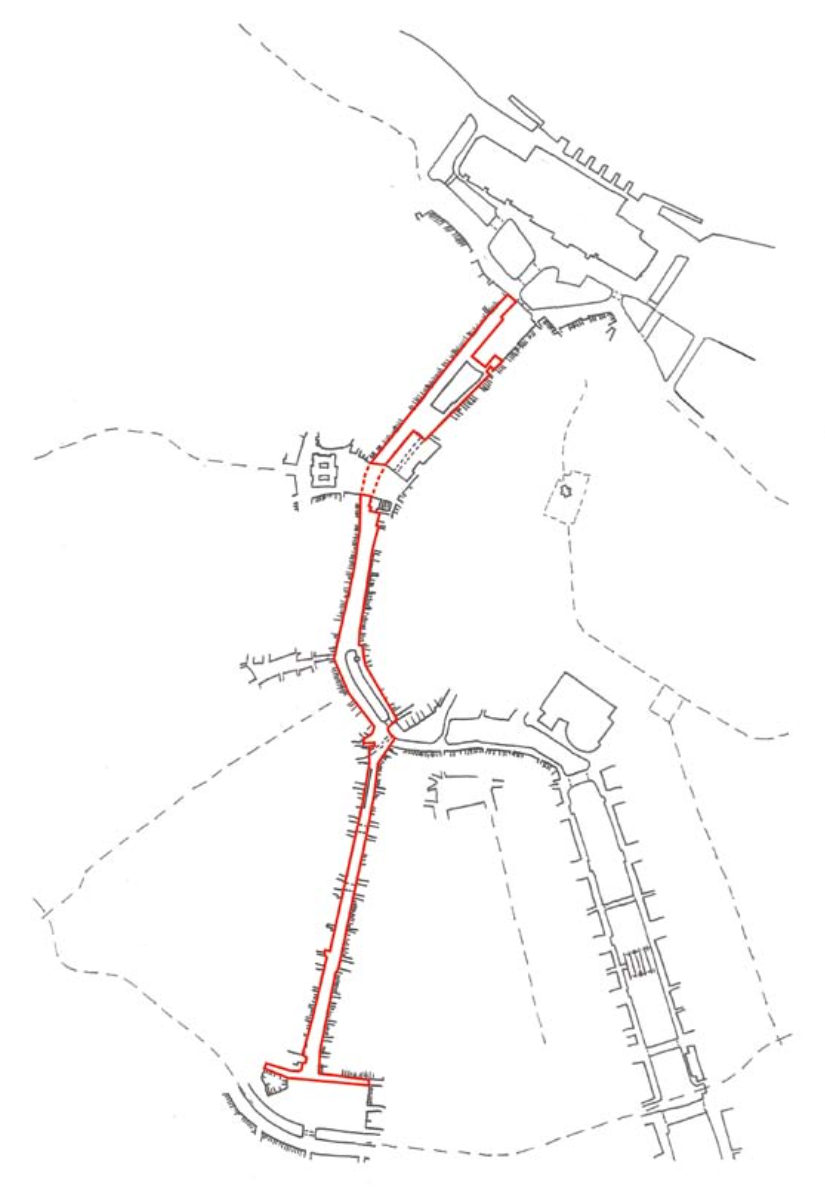

The Red Carpet, as projected in the plans.

In 2008 the Amsterdam city council introduced its ‘Red Carpet’ policy, aiming to improve the ‘allure and quality’ of the public space covering the route of the new north-south subway line (which is to be inaugurated in 2017) along the part that runs underneath the city centre. Certainly, public space is being improved, making it more pedestrian and bicycle friendly. But in the grand scheme of things, the upgrade seems mainly intended to facilitate a larger flow of luxury tourists and shoppers. Indeed, the Red Carpet strip has recently become a hot destination for global retail chains and investors due to soaring property prices in Amsterdam, an explosion of tourism, a wealthier consumer population, the outlook of the new subway line and a welcoming city council.

Haussmann

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the 19th century rebuilder of Paris, led the city’s largest redevelopment scheme in history, imposing a plan whose basic structure has changed very little in the many decades since. He cut stately boulevards through the city, demolishing the existing urban fabric and displacing populations and economic activity. The wide boulevards have since been lined with gracious buildings, housing the city’s wealthy and catering for their expensive tastes with boutiques and restaurants (not to mention an abundance of extravagant macaroon shops).

Outdated ugliness, new monuments

The master builder died in 1891. Yet his spirit lives on in a luxury department store that shares his name, situated on Amsterdam’s Rokin, one of the roughly four streets making up the Red Carpet. The store will inhabit a neo-monumental building on a plot where one of those ‘ugly buildings’ once stood, the pinkish marble-clad Fortis Bank building, demolished just 25 years after its completion.

The development’s website takes a perverse and almost poetic joy in the pneumatic muscle of its long-arm crane chowing down on the helpless bank building. The crane’s large jaws “will crunch through the various floors and pulverize all the rubble” and once it has made space for itself it “will advance over the rubble, eating through the building”. According to the article this bizarre spectacle was all watched over by admiring spectators, taking a similarly sadistic enjoyment in the blood sport.

In addition to the luxury department store, Marks and Spencer will move into another faux-historic building on the same plot. Retail and luxury department stores replacing a bank building in a perfect storm of creative destruction, the intention: to wipe out all trace of the recent past.

But to be honest, anything looking like it’s built in the 20th century doesn’t really fit a red carpet, does it? A 1960s modernist building on Damrak, the first stretch of the Red Carpet is also being renovated now. The ‘Rotterdam-like lump of concrete which was dropped on the historical inner-city‘ (according to the property developer who is redoing it now), is being dressed up in a cosy brick skin with the help of Robert A.M. Stern Architects so that Primark can set up shop later this year. Two other buildings from 1983 and 1987 have been stripped down and converted into glass boxes to house the suspicious fashion brand Forever 21 and national newspapers NRC. Basically all buildings that aren’t old enough yet to be considered heritage have been erased from the streetscape. Given the city’s cleansing craze, it’s interesting to think about the fate of all the shiny neo-historical buildings 20 years from now, when their sparkle has faded away.

Boutique department store

In its fascinating promotional video, the new Haussmann positions itself as having all you’d ever want in one place: the cosmopolitan qualities of London (‘innovation’), Milan (‘design’), Paris (‘charm’), New York (‘energy’) and Istanbul (‘mystery’). It will also house a Beauty and Beyond Centre, a posh restaurant and a food hall. Not a grimy one with street vendors of course, a yupster version as seen elsewhere in Amsterdam, or something like Rotterdam’s MVRDV-designed delirious food temple, but a proper high quality one.

Haussmann: the cleanup of Paris and Amsterdam

That’s the new Haussmann, now to the original. The four main functions of Baron Haussmann’s 1853-1870 urban plan for Paris were capitalist, hygienic, monumental and military. Let’s project them onto today’s Amsterdam.

Looking at it from a capitalist perspective, Paris had to become the perfect playing field for those with money. Efficient physical infrastructure had to be put in place so that modern forms of capitalist enterprise could thrive. In a wonderful contradiction in terms, only once everything was in place could there be laissez-faire. Fast-forward to Amsterdam today, we see a similar trend. Policy makers embrace foreign investors and global retail chains with open arms, so too successful metropolitan immigrants. Simultaneously however, a nationwide squatting ban is being implemented, social housing stock is being sold off and traditional shops make way for concept stores and hip bars that can afford the higher leases. A prime example is a snack bar that couldn’t afford the quintupled rents and was replaced by a hip new bar, which cynically recycled the name of its predecessor. In Amsterdam, a new hotspot pops up with every blink of an eye, serving the insatiable demand of the ever-growing population of privileged young white urbanites.

In order to create the favourable conditions for wealthy investors, residents, and tourists, things need to be spotless. Which brings us to Haussmann’s second aim.

Another function of the 19th-century Paris regeneration was a hygienist one: getting rid of filthy living environments. It is said that the concern for public health was only communicated to justify the massive renovation project. Amsterdam is also being cleaned up: the city wants to get rid of its famous Red Light District, which lies just a few metres behind the Red Carpet; the number of coffee and tourist shops is being confined. In virtually all urban situations, temporary creative projects are parachuted-in to imperfect places to attract new audiences and new investments. It signifies the direction in which Amsterdam is going: it’s on its way to becoming an incredibly liveable, comfortable, clean and pretty city; but of course, the cost is its soul.

Baron Haussmann’s third aim was to make the entire city into a monumental symbol of timeless grandeur, to legitimate the rule of Napoleon III. The inner city of present-day Amsterdam is similarly being turned into a conservative monument, a monument to itself and its history which leaves limited space for alternative narratives. Everything, old and new, has to have an air of splendour.

The final purpose of Haussmann’s plan was a military one. The new urban makeup of Paris allowed those in charge to easily crush uprisings; the wide, lengthy boulevards would make it easier for troops to move and for cannons to fire at a disobedient population. Because of Haussmann’s achievements, suppressing the 1871 French Commune was peanuts. Today, uprisings aren’t crushed militarily. Turning the city into a consumer’s heaven is more effective. Forcing people into over-priced apartments, expensive mortgages and dull but well-earning and demanding careers is the way to subdue the multitude in the 21st century. Along the Red Carpet, people are numbed by either the too-cheap-to-be-fair apparel from Primark, Forever 21, Marks and Spencer and H&M (with others such as Topshop close behind), offering the placebo experience of living a rich life; or by the high-end boutiques and department stores targeting the international super rich.

Luxurious tourist trap

A true Haussmann knows what he’s doing. The initiators of the new department store also correctly recognise that ‘there is significant unserved demand for a truly high-end retail service offering. Amsterdam has become an attractive city for the young and successful cosmopolitan citizen‘.

It really has. In the area around Haussmann, international luxury hotels are popping up, such as the W Hotel (in the city’s former telephone connection hub) with its Extreme Wow Suite, at a going rate of €2480 per night, the membership-based Soho House (in a former university building), The Hoxton and several others. A new Waldorf Astoria recently opened 200 metres from the Red Carpet, in a complex of six conjoined historical canal houses.

For the director of the Haussmann department store, Chinese and Russian tourists are the sought after customers, he told Amsterdam newspaper Het Parool. It only makes sense from a business perspective, since Chinese tourists’ spending on luxury goods in Europe has increased 18% in 2014, and 67% in the first quarter of 2015, compared to the years before, according to a CBRE report. The report also notes that international brands are looking for spots in Amsterdam, mainly on the so-called A1 locations, where the pedestrian flows are highest. The Red Carpet is one of those locations. All the while, voices saying Amsterdam is too crowded with tourists have never been so loud and numerous.

The question that must be asked is who in Amsterdam is benefiting from the city’s ‘progress’, especially concerning the influx of foreign investments and multinational chain stores. Sure, they will generate jobs, more amenities and more economic activity. But to whom does the city belong after prices have been driven up, property has been sold to Bahamas-based holding companies, and a place that once catered for a rich mix of people from various backgrounds has been turned into a consumption experience?

Of course, the name of Amsterdam’s newest upscale spot isn’t derived from the ruthless Parisian planner. It’s a nod to Boulevard Haussmann in the French capital, a street that is littered with luxury stores. But there’s a lingering irony. Given Amsterdam’s cleansing wave, the Haussmann label comes with the unavoidable whiff of urban sanitisation.