In his seminal study The Image of the City Kevin Lynch speculates briefly on automated navigation as a way to support wayfinding. In the book, he asserts that it would be potentially very useful, but precarious to rely on because ‘orientation fails if the device is lost’. Published in 1960, his predictions turned out to be pretty accurate. In light of today’s culture of navigation, it has become increasingly important to re-evaluate the ramifications of his discourse.

Observing ‘the city’ as a place which had become fragmented and cluttered by roads and random signs, Kevin Lynch was among the first to attend to the public’s concerns, trying to unravel their spatial confusion. The new visual order was ambiguous, to say the least. Difficult to read, and even harder to internalize. The mental picture of the city; the ‘strategic link’ between the city and people’s ability to navigate it, was clearly compromised.

Could perceptual psychology cater for a more tangible form – a form that could be readily perceived and kept in the mind’s eye as a clear image against the roar of the metropolis? And could this form perhaps then be complemented by some external device, some type of automated navigation, building on the same perceptual principles? These questions began to materialize with the appearance of the concept of the ‘cognitive map’.

The cognitive map and The Image of the City

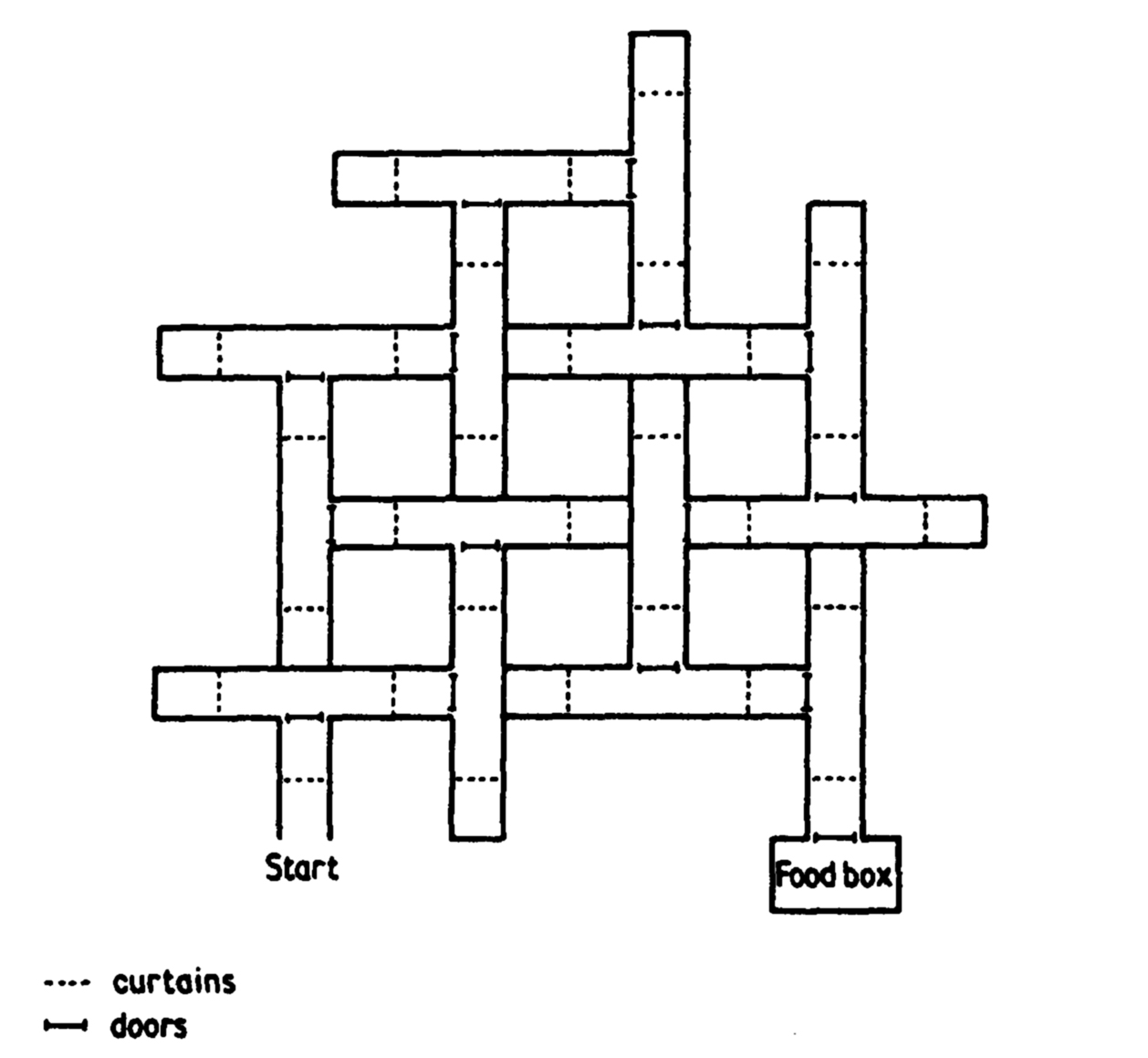

In 1948, psychologist Edward C. Tolman made his laboratory rats navigate an elaborate maze. It was a classic experimental design with two groups of rats running two trials each: in the first trial, only one of the two groups would receive a reward for completing the maze; in the second trial, both groups would receive the reward. In line with expectations, the reward-group outperformed the delayed reward-group during the first trial. In the second trial, however, the rats in the delayed reward-group were the champions.

How did the rats in this group pull this off? They were not acting from a stimulus-response relationship, as they had received no reward at the end of the first trial. Tolman inferred that they must have developed some form of internal representation of the territory, a ‘cognitive map’ that allowed them to navigate the maze as quickly as they did.

Tolman’s study became an instant classic. It signaled a shift from behaviorism to cognitivism, from pairing of stimulus and response to goal-directed processing of information. The concept of the cognitive map (a mental representation of survey knowledge) became widespread.

The emergence of this cognitive map clearly inspired Lynch towards further inquiry. He asked the residents of Boston and Los Angeles to sketch out their daily routes from memory (‘as if you were making a rapid description to a stranger, covering just the main features’).

The cognitive map was of course not an actual picture: it was a symbol-structure on which mental processes operated to retrieve information; a structure producing visuo-spatial representations of the city. Lynch’s interviews generated stories of a sort, of street signs and storefronts, slopes, turns and vegetation. The stories conveyed objective survey knowledge as well as idiosyncrasies, gaps and ambiguity. In Boston, for example, most distant landmarks were ‘bottomless’, said Lynch’s report. ‘They had a peculiar floating quality.’ Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, residents would mentally walk across the Hollywood Freeway as if it didn’t exist. They described the experience of driving that freeway: ‘as if you were going somewhere for a long time, and when you got there you discovered there was nothing there, after all.’ If anything, the method revealed the city as a lived experience.

Despite having a keen eye for such remarkable subtleties, Lynch chose to bypass idiosyncrasies to work the data from his study towards a more tangible result: the city-image. A superimposition of drawings and descriptions, the city-image revealed those visual attributes of the city that were clearly articulated by most people. These attributes – paths, nodes, landmarks, edges, and districts – would add up to an imageable form, like a visual syntax, directly perceivable, making it clear what was figure and what was ground. Note the shift from street-level experience to the birds-eye representation that Lynch used to depict the five elements.

The depiction can be read as an attempt to a symbolic logic that could aid the public’s processing of information when moving from A to B. A graphical language that would facilitate the interaction between man and city and optimize reasoned decisionmaking while underway.

Outsourcing the strategic link

Lynch invented the term ‘imageability’ to describe the degree to which the urban environment can be perceived as a clear and coherent mental image. Reshaping the city is one way to increase imageability. But what if the cognitive map were complemented by some external device? Lynch proposed that this too could strengthen the mental image and effectively support navigation.

Writing in the late fifties, he referred to Directomat, a machine that was piloted on the New Jersey Turnpike. Directomat issued printed directions to places and major highways from ‘Aqueduct Raceway to Zoo, Bronx’ – very effective to keep people oriented. Outsourcing was imminent. But Lynch himself had reservations: it would be tricky to rely on such a device because very quickly one could become too dependent on it; more importantly, the depth and vividness of one’s mental image would deteriorate. In addition to this, the Directomat (and its successor) would have to be continuously updated to the present situation.

In 1985, the extended cognitive map became a reality; albeit in a rudimentary form. Anterior still to GPS, the contemporary electronic devices produced calibrated turn directions on a monochrome vector map. The experience wasn’t seamless – the area of Los Angeles was delivered on four cassettes (one had to be quick on the mark). As most drivers had problems interpreting the map when it was not aligned with the direction they were going (let alone the car-cursor travelling the map) the driver-centric perspective was introduced.

Following this introduction, the map would now turn and move around the cursor in the middle of the screen, always heading up. This allegedly echoed the practice of pre-modern Polynesian navigators who would perceive themselves in the center of a projected navigational space, with ocean currents and islands revolving around them (instead of the other way around). An inversion of figure and ground.

Floating safely up in the air

First the map was outsourced to an external device, then it started to move. Once perfected, the result was a seamless yet detached interface between the driver and the landscape. No more direction ambiguity or lack of relation, no more gaps in memory, with the image as clear as day. You could now drive onto the Hollywood Freeway while your car predicts the next exit. The aerial perspective on your display would suggest that you are floating safely up in the air. You would glide effortlessly from landmark to landmark as your destination flows towards you. Instead of going ‘from somewhere to nowhere’ you would remain always in the center. No resistance or disturbance, or so it would seem.

Apparently, the sequence of shift and inversion produced a disembodied gaze. A sense of hovering above secure and stable ground, removed from the fragmentation and cluttering on street-level. As Hito Steyerl argues in The Wretched of the Screen it is not the illusion of stability that is in itself problematic – traditional maps create that illusion as well. Problematic is that the map takes priority over the territory. A Death Valley park ranger recounted a number of critical incidents of people following disused trails, disappearing into remote areas of the Californian desert: ‘It’s what I’m beginning to call death by GPS’, he said.

Lynch did issue the warning. ‘To become completely lost in the modern city is perhaps a rare experience’, he wrote, but once disorientation occurs ‘the sense of anxiety and even terror that accompanies it reveals to us how closely it is linked to our sense of balance and well-being’. One cannot help but view the Death Valley desert-case as emblematic of such anxiety. For Lynch, external support was meant to complement the mental image not supersede it, it was meant to heighten the observer’s attention and enrich the experience of the landscape, whereas today’s routine achieves just the opposite.