Listen to this episode and subscribe to the FA podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Overcast, or wherever else you usually get your podcasts.

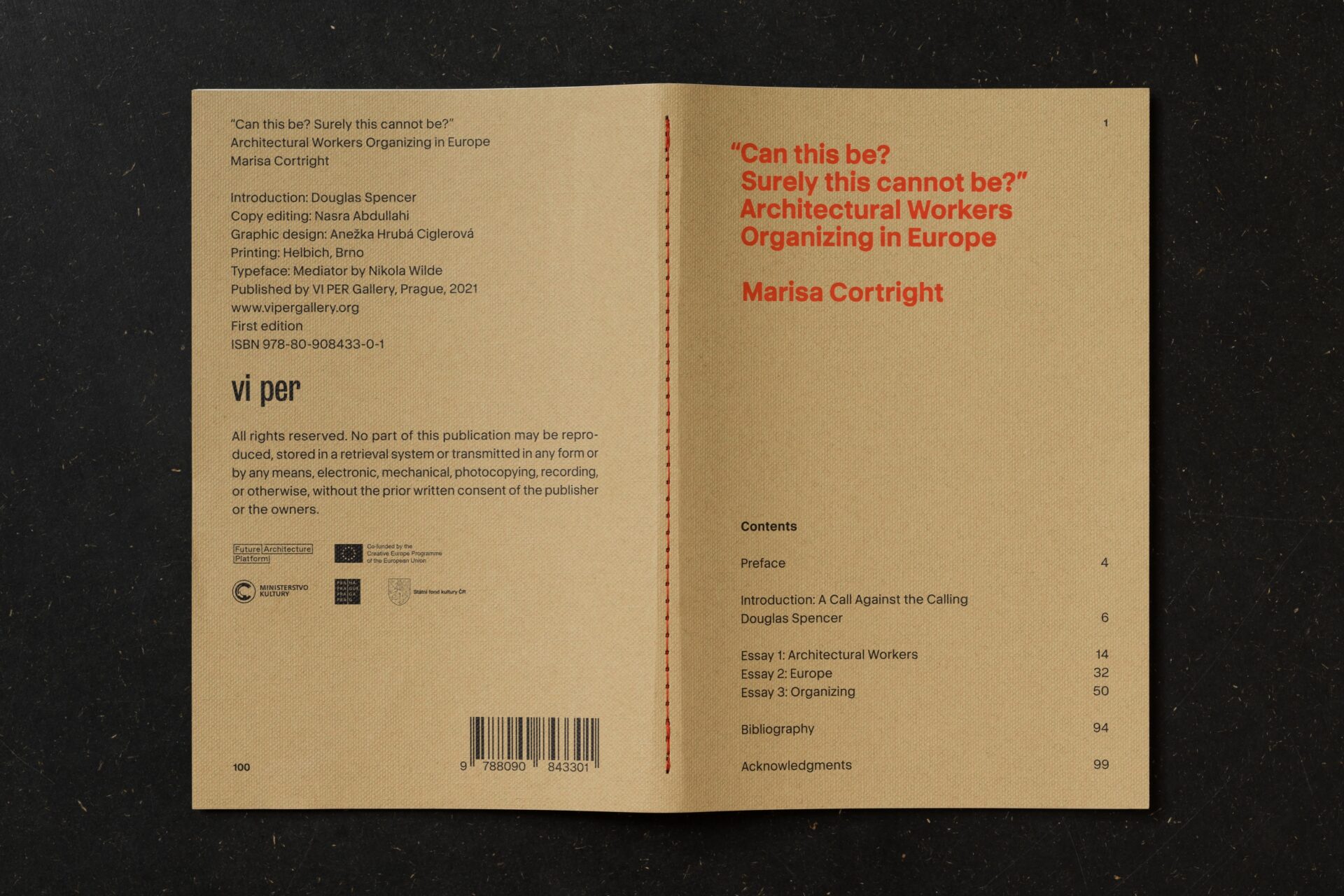

This episode is the first of a two part interview with Marisa Cortright, author of the Failed Architecture article “Death to the Calling: A Job in Architecture is Still Just a Job” and, more recently, Can This Be? Surely This Cannot Be?, a book composed of three essays on the subject of architectural workers organising in Europe.

In this first part, Marisa and host Charlie Clemoes speak about their shared position as non-architects working in architecture, then they go on to speak about the function of certain keywords in entrenching existing power dynamics in the architectural practice. But first, they start by talking about the book’s structure and the content of the book’s three essays and particularly its second essay, which explores the boundaries of Europe and its historic role in facilitating iniquities, both in the sector and the world at large.

Listen to the second part here.

Below is a transcript of the conversation.

If you want to continue the conversation, chat about FA matters or talk to one of our editors, head to our Discord server.

Marisa Cortright: The book does jump around a good bit. I have been reflecting now that it’s over with and published six months on: “Gosh. What was I doing?”

Charlie Clemoes: Yeah, tell me about that, was the process you kind of trying to get to grips with some of the various strands of that thematic universe that this project falls within?

MC: Yes. And this was an unwise decision to try to bring together those threads into my gesamtkunstwerk, or whatever, my total art of all the things I was concerned about in architecture, starting with the first essay, the most straightforward part of the book, on the architectural worker: who are they? Who might be included in that group? Why are we calling them an architectural worker? Because that was an extension of the Failed Architecture piece. I originally was discussing the need for this term “architectural worker”.

Then there was the second essay on Europe. That was the wildcard because I am not a historian of the formation of Europe, throughout the centuries, nor the contemporary development of the European Union. And I think I set that up in such a way as to say look, I’m coming at this from the perspective of someone who is realising that Europe poses this material problem or at least certain regulations and customs of the European Union as it exists today are a problem for architects or workers based on what I’ve seen in my workplace. From there, I went from Lefebvre, all the way to Walter Rodney, and Maria Todorova, trying to bring together both this initial issue of why are there so many Southern Europeans cycling in and out of big architecture companies in Northern Europe, to what it means for me to be in Croatia, a relatively new country, on the edge of Europe, we might say, and in this region of the Balkans, which has historically been in a kind of tug of war, between whether it’s part of Europe or whether it’s Ottoman, in some respects, but it’s important to think also about Croatia as one of the countries that provided the so-called “Gastarbeiters” or guest workers to Germany. There were a number of these guest worker programmes during the 60s and 70s in countries in the north of Europe, where workers from the south of Europe would migrate, ostensibly as guest workers or temporary workers, to these countries in the north of Europe, where they would earn far better salaries than they would ever be have been able to in their original countries. And then they were largely expected to leave and go home, once their stay was was no longer welcomed by their employers in the north of Europe. And this has created obviously, interesting immigration dynamics over time, as guest workers settled in countries in the north of Europe. But we might think of that programme, as in many ways, informing how migration works in Europe now. It looks a little bit different because of the so-called freedom of movement that the European Union grants to European nationals who now have the right without any restrictions on how long they live in another country and the EU to move at will. But there are still restrictions, of course, on people who are outside of the EU. So instead of this North-South divide, which we see but in a different way. now there’s a kind of East-West divide of countries who are not in the European Union but are from Southeast Europe, like Serbia, or Belarus further north, the point being that there are always going to be workers who need to migrate into the European Union. into Europe into these “European” countries to find work and who are at a disadvantage for that reason and who are economic migrants at the behest of a very violent and all the more sophisticated form of immigration control now more than ever, and of course, one of the dynamics that I track in the book is immigration from the Middle East and from Africa and the ways in which the EU has set up the so-called Fortress Europe to expand the border of the European Union outside of the countries that comprise it into the countries where immigrants or would-be immigrants will be coming from and this is really disconcerting for European nationals because it removes from their consciousness any awareness of this border of Europe. The freedom of movement means that they don’t experience it and the fact that the border has been displaced to outside of Europe means they don’t see it at all. They don’t see that that’s the Mediterranean they don’t see police beating people in the forest, and they don’t see the violence that the European border entails. And while that might not seem like a specifically architectural problem, there is still this insistence, I think, in architecture as well as other middle class or so-called wealthy professions or industries that Europe is this unbridled good, it’s something that we have to be so thankful for because it’s offered so many opportunities for us. I think we really have to be careful about what we accept when we think about Europe in such an unqualified way.

Finally, the third essay concerns the perhaps more relevant subject of organising architectural workers which we’ve seen a lot of good examples of in different cases across Europe, and I thought that would really be the thing that would be useful for people to see: that there are a lot of different things going on and that we might learn from other contexts, it doesn’t just need to be people in the UK learning from other people in the UK although obviously that’s happening and it’s a good thing, but they also need to know what’s going on in Spain, in Croatia, for that matter, and for all the ends of Europe to connect and that was I suppose my rationales for bringing the Europe part into this idea of architectural workers organising, there needs to be some kind of geographical basis because there is this, let’s say, geopolitical force that governs everything that’s happening here.

CC: Sure, no, but the whole essay on Europe, you called it a wild card but there are obvious reasons why it’s useful, and I have to say, that chapter is one of the main things that I found really illuminating about the book, in terms of situating the subject of architectural work in its wider context. I was thinking about the workers’ inquiry that we’ve been pursuing at Failed Architecture and how quite a lot of the time it comes up that the main people being exploited in the Netherlands are people either coming from Southern or Eastern Europe or from outside of Europe, but nonetheless, the geographical scale on which these sorts of things are happening is within this zone, which is actually kind of an anomaly as continents go because it can’t really be defined according to a geographical line that says this is the end. I think that’s something that people forget quite quickly. Not enough people know about and realise that the struggle has to happen on that kind of scale. It would be quite nice to talk a little bit more about the original article, I guess, the way that we came in contact with you was this article Death to the Calling and that seems to be. to a certain extent, the jumping-off point of the book. I’m wondering, I guess as a starting, point, what your own position is in relation to the field and how that affected you observing this notion of the calling because obviously, you’re an architectural worker but you’re not an architect. or you’ve been an architectural worker, but not an architect, and it gives you this, I feel very similar in a sense, like I’m an architectural worker, to the extent that I’m a teacher of architectural theory, and I’ve worked in practices as a copywriter, and I’ve written about architecture, but I’m in no way interested in this work as a calling. I’m fascinated by the subject. But yeah, can you talk a little bit about how your own position informs your entry point into theorising this subject?

MC: Certainly, when I wrote the original article, I was several years into working at an architectural company and was starting to understand what that meant for me as someone who wasn’t an architect, I found it very strange, particularly in an architectural company that really traded in these maxims of belonging, of a certain kind of high-end design that attracted only the very best from the best schools and who were really in it for all that it took, who would be willing to engage in the kind of unpaid overtime that we know is so rampant in the profession and then sitting on the other side of that watching that happen, but not being subjected to it to the same extent in the sense, not needing to work on the weekends, for instance, or feeling as though I could say, “No, I’m not going to do that” because I wasn’t working on a project team, but on a different kind of team. That really struck me the wrong way. I felt really bad for my co-workers. To put it in the most basic of terms. I thought, “This isn’t right”. And of course, it just is that way, but then I got me thinking “where do we go from here?” Because I’m not the only one who feels this way. I knew that the architects know that this isn’t right. But we need to develop some kind of way to talk about it. And one of the ways that I started to think about it for myself was this differentiation between architectural workers who are subject to the calling, namely architects, and then those of us who are just working there because that’s the job that we’re qualified for and that we happen to get and we’re happy to take on a paycheck every month for. The fact that that starts in the architectural office, I think I was still dealing with a lot of the minute hang-ups that I had with the particular company that I was working for, I tried to make some certain digs or some certain critiques of how that kind of office operates, but now that I’m not working in that company, I’ve started to think of that dynamic of architectural workers, both the ones subject to the calling and those who are not in a broader scheme of: “how does this function kind of across the industry? How does this function not only in the context of private architectural companies? But particularly those kinds of architectural companies that are located in places like the Netherlands?” which has, you might say, a larger number of architectural workers who are not architects. They’re bigger companies who export architecture around the world and so they need a marketing team, who need people who do copywriting. They need lawyers and accountants to the extent that smaller offices simply don’t have the financial resources for. So it would be architects trying to cover those kinds of things themselves and holding within themselves this dual role of “well, on the one hand, you’re an architect who’s called to do the architecture part of it, but on the other hand, you have to do business development because you can’t afford not to do it”. So I think it’s interesting to think about this dynamic across Europe again, but coming back to the original article and how it gets to the book, I think the article was my particular concern in 2019: “What has this experience been like for me?” And then I thought, “well, really I need to try to expand think about how other architectural workers are experiencing this dynamic, but also where they think they should be going”.

CC: On this. just from a personal perspective, I haven’t had that much experience doing this because of the like nature of the work culture. My one time really kind of being ensconced in an office. I was really struck by the expectations placed on me even though I wasn’t an architect. The real dissonance. I’ve never known someone to so blithely expect submission to a work rate that involves weekends, involves staying the length of time that it takes for a job to be finished and yeah, the taken-for-granted attitude of the people in management positions to the idea that like, it’s not even a question. It’s not open for debate, “Yeah, but we need to finish this now. So you’re staying.” Like it’s almost unconscionable the idea that you’d be like, “I have something to do, I’m going”. It is funny that this attitude does come up against reality in all sorts of situations. I’m an outsider. I haven’t gone through the educational churn that normalises the idea that you should stay up until the job is done and you should love your boss, and you should feel like you’re part of a family that it is this kind of hero’s quest (to use your phrase at the beginning of the article). It’s not those things for me. I was just a journeyman writer. I just wanted to get a bit of money and I remember the negotiations I acted how I normally act in negotiations for what my rate would be. I say that “this is my rate and I’m not going lower”. They seemed to have gotten used to the idea that people would submit to whatever offer. And I don’t even really play hardball in those situations. Anyway. I didn’t know if you felt that same weird dissonance of like, “Yeah, I’m not gonna do that”.

MC: Most definitely. And I do think you’re right, that the submission or at least the acceptance of that kind of work schedule, is inculcated in architectural education and that architectural companies really benefit from not having to do the work of getting their employees to submit to it because they’re already used to it. They accept it. As a given. But I do think they find certain rhetorical ways to encourage it, to continue to normalise it, particularly with younger employees who are pushed the hardest because they are the most precarious maybe because they have temporary contracts and they don’t want to be seen as slacking because they would be the first to be let go. Their employers find certain phrases or activities that try to encourage this sense of belonging. And it’s so difficult to pinpoint when that goes from being something potentially good because it might give someone who has moved to a new city some sense of a place: that they’re doing an internship, they don’t know anyone, they need to feel like they belong. But it can very quickly become a negative impact of “well, this is the only place I have and so I’m going to spend all of my time here”. We hear that from particularly small companies, but also large ones who refer to themselves as “families”. How would you leave her family? There was one woman I interviewed in my book, who said, Well, I know the only reason why my manager is saying that we’re a family is so they can call me up on Sunday and have me come into the office.” It’s harder to turn that down once there’s this expectation of a close intimate relationship with someone like that.

CC: …This feeds into the next thing I wanted to talk about. For a while now, I’ve been really into the book Keywords of Capitalism by John Patrick Leary. I find it’s quite a useful book for conceptualising the way that architecture speak unfolds not just in the workplace, but also in the way that architecture practices speak about what they do, and what kind of projects they’re involved in. Leary talks about “sustainability” for instance. He has a great chapter on “design”. He talks about, for instance, creative terms that obscure the worker-boss relationship to turn wherever you are into creative experience, which obviously works differently in different places that, you see it working very badly in the hospitality industry, trying to turn these sorts of things into a kind of creative thing, which hasn’t worked as well. But architecture is ready-made, in the sense that, indeed, the educational system prepares architects for this way of thinking and the way that the whole profession sells itself to clients and other industries it works for, very much playing on the left-side-of-the-brain thinking. we can do the things that go beyond automation and offer more ineffable, hard-to-pin-down skills. But he also talks about the way that certain words engender these kinds of relationships. So yeah, talking about family. Could you talk a little bit about this yourself?

MC: Yeah, I think I think maybe the trickiest one of them all, and that I’ll discuss off the top because no one has really managed to crack this. I don’t know if John Patrick Leary picks it up because it does seem kind of particular to architectural or urban design or even an engineering context: the figure of “the user”. I rely in my book on, unfortunately, Henri Lefebvre, to talk about the user: who is this group of people that we’re supposed to be working for? It’s obviously not the same person or group of people as the client, or the financer of the project or the government, for that matter. But many of the people I spoke to were coming back to this idea of this disconnect in the language, that they were able to use as people trained as architects and the people they were ostensibly meant to be designing for

CC: Something you’ve mentioned in the book, you quote, Sasha Costanza Chock who notes that “designers tend to unconsciously default to imagined users whose experiences are similar to their own. This means that users are most often assumed to be members of and hence unmarked group”.

MC: Yeah, not only is there a lack of a good term to use for them, whoever they are, but there is also a lack of a shared vocabulary, that might bridge people the design profession, let’s say architectural workers, and their ostensible subjects. Again, I’m locking the words myself, so I’m kind of dancing around deciding on one but we could say “user” as the stand-in or the placeholder, and then where we go from that lack both of an idea of who we’re supposed to be working for and of how we’re supposed to be communicating with them. We lack the capacity to understand the purpose of architecture, or how, in combination with other consultants, we might talk about architecture, how are architects supposed to be working with other kinds of people to develop these projects, and how are they supposed to be involved in broader societal organisations to bring about things that are good for people. At the most basic level, we’re talking about really, really basic things. So this lack of vocabulary in a way is almost more damning than the words themselves, which are fleeting. And to say about fleeting vocabularies, there are certain phrases that cycle in and out of relevance or usefulness for people, I would say amongst them our diversity, inclusion, and equality, we can add this idea of DEI: diversity, equality and inclusion that is now a professional capacity unto itself. These words are all around us all the time. You have to be really really careful about what they’re doing and whether they are acting in a way that is helpful for us. We might again dance around defining “us” because I think that that can be itself appropriated. But let’s say that there’s, on the one hand, a lack of certain kinds of terminology and, on the other, there is this very slippery terminology, and what I try to argue for in some respects is landing on a vocabulary that cannot be co-opted, vocabulary that is not so slippery. For instance, abolition organisers were really good about this in the summer of 2020, during the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd, there was a strong insistence on the demand to “defund the police” and defunding the police is not a phrase that can be co-opted, and indeed it has not. But “reforming the police” are finding these other kinds of let’s say lesser versions of change, those certainly have been utilised in a number of different ways. And I think there’s something that architectural workers can really learn from this rhetorical lesson of “how do you arrive at a demand that cannot be co-opted? How do you arrive at certain kinds of frameworks that cannot be co-opted”, So I’ll give one more example returning to diversity, for instance, instead of referring to diversity, how do we talk about anti-racism? How do we talk about anti-sexism? How do we talk about the particular forms of discrimination that a word like diversity would be covering up?