A companion on-demand streaming of Peter Snowdon and Rima Essa’s 2007 documentary film Drying Up Palestine is available on our site until midnight ET September 1st to raise funds for water distribution and infrastructure repair in Gaza. Header image courtesy of Anne Paq for ActiveStills.

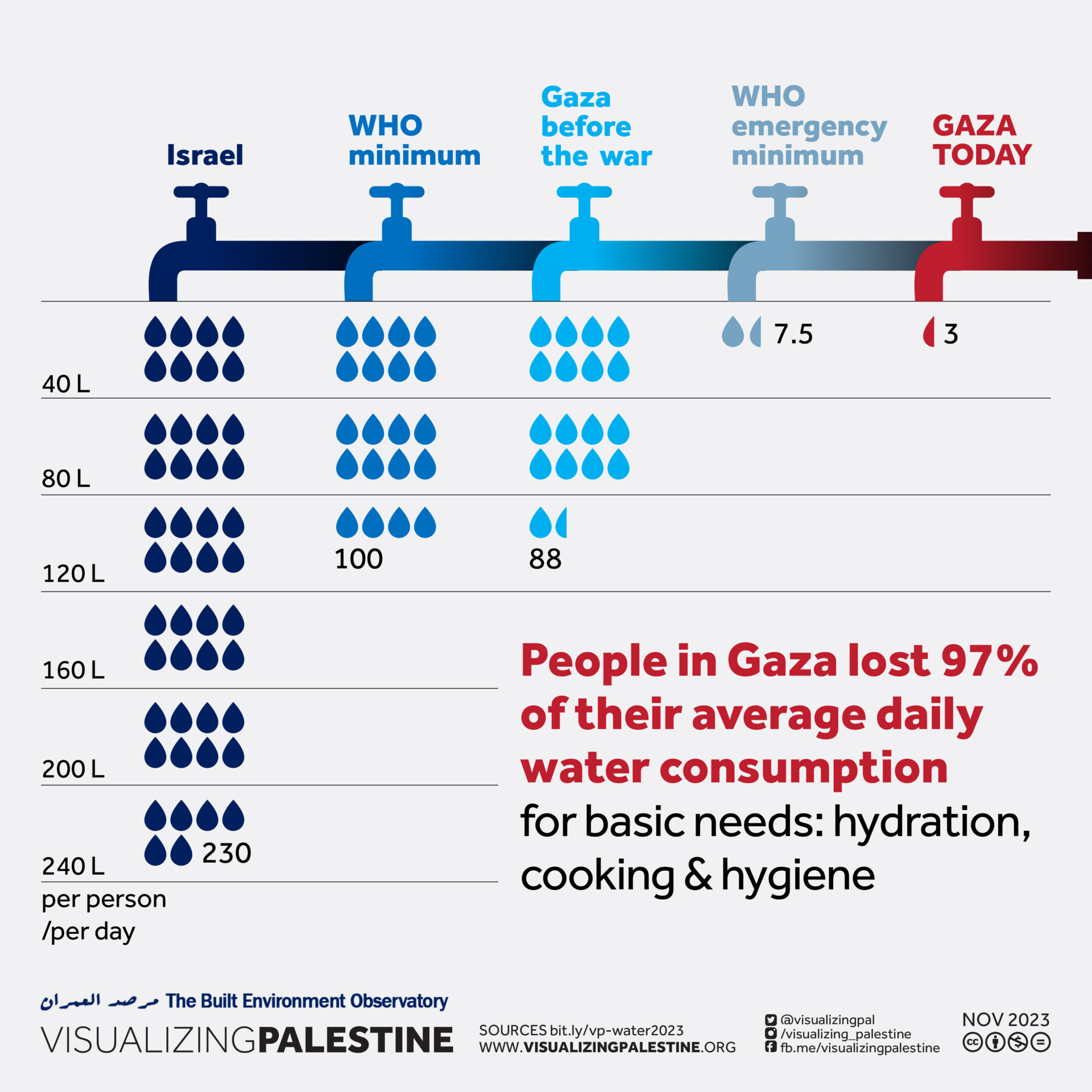

Sasha Plotnikova: Last October, one of the first escalations Israel took as part of its genocidal war on Gaza was turning off the water supply. Since then, the IDF has continued to target the supply of water: water tanks, water treatment facilities, and sewage pumps have all been attacked, resulting in widespread dehydration and water-borne diseases. Now, no soap or cleaning supplies are allowed to enter Gaza, deepening the hygiene crisis created by the lack of safe water. It’s important to note that Israel has militarily attacked Gaza’s water infrastructure in recent memory, during Operation Cast Lead in 2008, and Operation Protective Edge in 2014. Can you give us a picture of access to potable water in Gaza between these times of pronounced military violence?

Muna Dajani: What we’ve been witnessing for the past ten months in Gaza is a cruel intensification of the systematic deprivation of Palestinians from their right to water. The fact that Israel was able to switch off the water supply to Gaza indicates that it completely controls Gaza’s water access, especially potable water. Over the past decades, Gaza has been turned into a place where water has become a resource that is unfit for human consumption, and this is a process blatantly imposed by Israel and sanctioned by the international community. The situation was so dire in Gaza even before October 2023 that a lot of international organizations were calling it an unlivable place, or that it would be uninhabitable by the year 2020. But these predictions don’t actually tell us how and why Gaza has become so uninhabitable. This is not caused by a natural disaster or apolitical factors like the climate, water scarcity, or even merely explained by over-extraction. It’s been systematically imposed on a place that has been completely confined, segregated, put under siege, and disconnected geographically from the rest of Palestine. Just like any other place around the world, Gaza should be able to depend on other places that may have more abundant resources to sustain its environment and its people, but the siege and Israel’s systematic settler colonial control over land and territory prevents that.

MD: When it comes to water, Gaza has never been seen as part of the continuum of the Palestinian geography under Israel’s occupation. For example, water is more abundant in the aquifers of the occupied West Bank, but instead of that water being sent to Gaza, it has been exploited exclusively for the benefit of the Israeli settlers. In the case of Gaza, the threshold of overexploitation of freshwater was reached by Israel in the 1960s, by their own standards. At that point, Israeli authorities started thinking of technological solutions to make water more available. This led to advancements in wastewater treatment plants, reuse schemes, and desalination plants, among other technologies. Meanwhile, Israel maintains its hegemony over the existing resources.

Looking at the statistics alone, we may find it hard to see how this was allowed to happen for so long, and how it is that, instead of finding political solutions to end the Israeli siege on Gaza, the international community devised solutions that maintain the siege. The humanitarian approach is a band-aid solution to an inherently political problem that requires a political solution. These humanitarian mechanisms are part of a system that largely places emphasis on the construction of infrastructure and finding apolitical technological solutions to alleviate people’s suffering. But desalination plants, wastewater treatment plants and other infrastructures depend on a continuous source of energy, which Israel prevents Gaza from having and completely controls. Every time there has been an assault on Gaza, reconstruction is required to revive the infrastructure that provides potable water. But because of the blockade on building materials, this isn’t always possible, so people have had to rely on other water sources, leading to the overexploitation of the groundwater. Before October, Gazans were already consuming highly polluted and contaminated water. In 2014, Dr. Ghassan Abu Sitta and Mark Zeitoun noted that the Israeli siege on Gaza and the occupation of Palestinian lands and resources have created a “toxic biosphere of war.” Today, Gaza’s water and wastewater systems have been completely destroyed by Israel and this has led to the rapid spread of waterborne diseases, including Polio and Hepatitis A, due to contamination and pollution widespread across the devastated Gaza Strip.

SP: As you and others have pointed out, Gaza embodies an extremely accelerated, intensified version of what the rest of Palestine has been experiencing under Israeli occupation. You’ve devoted much of your research to showing how the stranglehold Israel keeps on Palestine’s water is a systemic, entrenched instrument of the occupation, not only in Gaza but also in the West Bank and in Israel’s occupation of the Syrian Golan Heights. Under Israeli occupation, water is a commodity to be purchased from Israel. Can you talk about the legal context that led up to this?

MD: I think at the heart of it, it’s about those who colonize and have military power separating colonized people from nature. It’s about turning resources into commodities and turning people into consumers. The occupying state puts rules and jurisdictions in place that govern the way water is dealt, used, produced and exploited, dismissing the presence of Indigenous communities and their history of being part of that ecosystem and using that water.

Mekorot, for example, the Israeli company that controls almost all of the water resources in the Palestinian territories, was founded with the mandate to develop water infrastructure that would exploit local resources exclusively for the benefit of the Zionist project. After 1948, Mekorot became the main body that carried out the construction of this water infrastructure alongside Tahal, the company that was in charge of the planning of water resources. Since then, many communities in Palestine and the occupied Golan Heights have had to pay Israel for water and to connect themselves to the water network. For example, farmers had to develop their own infrastructure of pipes and pumps to actually get their fair share of water. The severity of the water injustice varies by location, but all of Palestine is marred by injustice. There are even Palestinian communities inside 48 Palestine that are excluded from the water system, to facilitate the development of Israeli kibbutzim, towns, and cities.

Israel has framed water as a national security issue, but it’s also about upholding Jewish Zionist sovereignty. This takes us to how water has shaped borders across our region. Under the British Mandate in Palestine and the French Mandate in Syria and Lebanon, the Zionist entities were pushing to make sure that the future Zionist state would include access to resources. The 1959 Water Law, which followed Israel’s occupation of the rest of the Palestinian territories, imposed a complete control over resources that we see still in operation today. Water became public property in a way, but governed by a highly centralized authority.

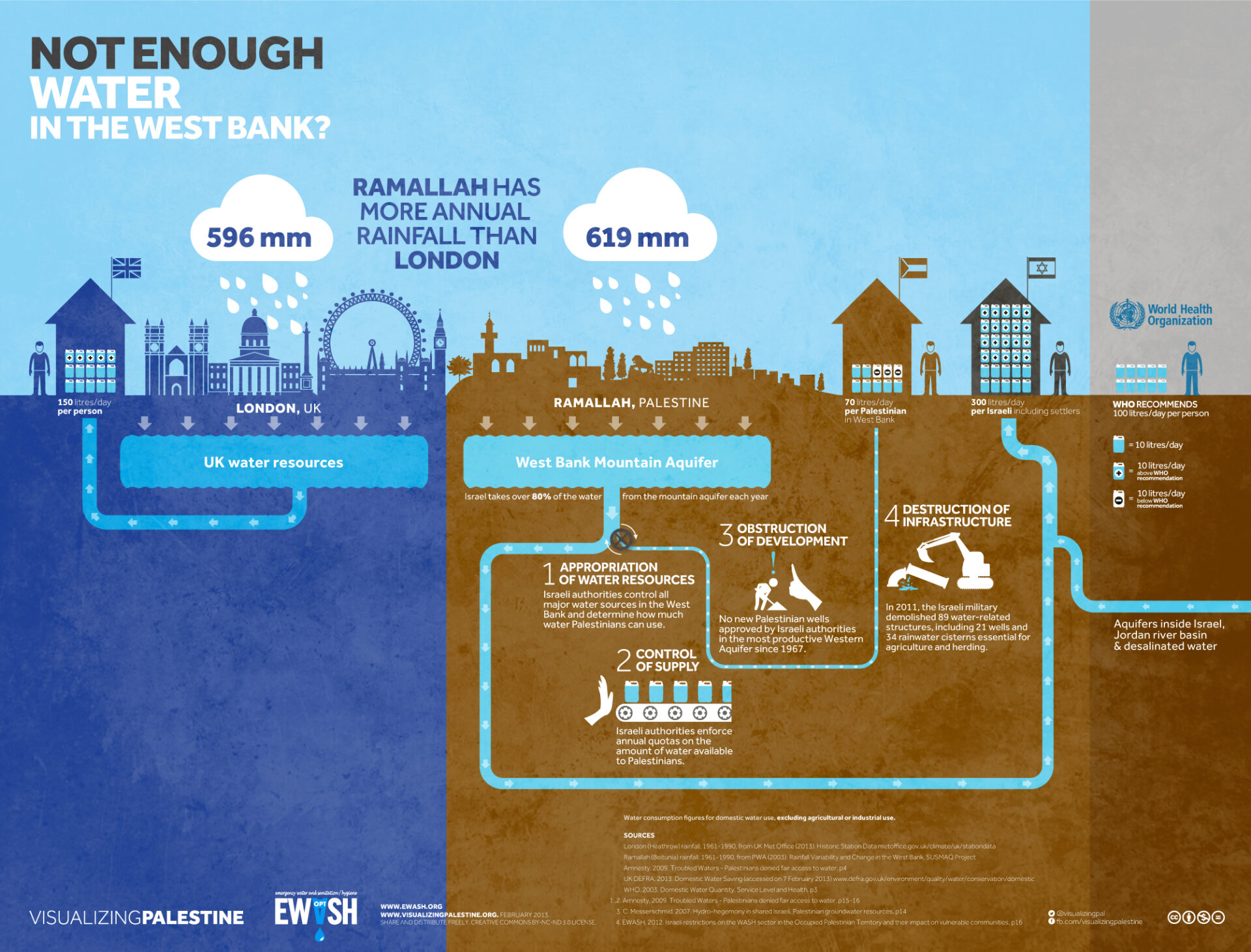

Israel controls the West Bank’s water supply through the Joint Water Committee (JWC), another institution established to maintain control over how water is governed and who approves new infrastructure. This JWC system makes permit approvals almost impossible for infrastructure. There are areas of the West Bank where drilling deep wells has not been allowed since 1967. In Area C in the West Bank, everything operates under the logic of a humanitarian case, because Israel does not allow any type of infrastructure to be built in the Palestinian communities there and demolishes anything built without approval. The infrastructure that Israel permits is usually infrastructure that benefits the settler population while keeping Palestinians reliant on the Israeli water sector.

SP: This infrastructural violence that you’re talking about is much less visible from afar than, for example, the land grabs carried out through evictions and settler violence in the West Bank. Where Palestinians maintain a presence on the land, the aquifers beneath them are claimed by Israel, but this rarely factors into conversations around annexation. Do you consider Israel’s control over the water infrastructure in the Occupied Territories part of its project of annexation?

MD: Definitely. It has been said for decades by Palestinian civil society organizations and researchers that annexation and ethnic cleansing are happening in the same areas of the West Bank where the development of Palestinian infrastructure is being denied. There is a common type of footage showing Israeli soldiers coming in with bulldozers to different villages and demolishing whole Bedouin communities, especially in the South Hebron Hills, in Masafer Yatta. They make sure that each water tank is punctured, water flowing out as a signifier of domination. They frame this Palestinian presence as illegal, and the infrastructure as part of this illegality. And in the background, Israeli settlements flourish with unlimited access to water for domestic and international agribusinesses which make huge profits off of stolen land and water.

So this is a project of annexation in that sense, but it’s also a project of ethnic cleansing, because communities are deprived of the basic resources that can sustain life. So they’re pushed elsewhere either through this process or through evictions, whether it’s to Area A or Area B, which are the “approved” places for them to exist. In those areas, Israel’s control over water is more invisible. In my research, I talk about uneven waterscapes because across all the fragmented geographies in Palestine, there are differing conditions that allow the Israeli settlements to flourish while Palestinians are subjected to systematic thirst and hunger. For example, Ramallah relies on Mekorot pipelines for its water supply. Every summer, when demand is high, the water supply for the big Palestinian cities like Ramallah is completely reduced by Mekorot because the priority goes to the Israeli settlements.

“Despite the fact that Ramallah receives more rainfall than London (one of the world’s most renowned rainy cities), the average West Bank Palestinian can access only one quarter of the water available to the average Israeli each day, and 30 liters less than the World Health Organization’s minimum recommendation.” (2013)

Visualizing Palestine

MD: I want to clearly speak about the complicity of international actors in the perpetuation of this violence. Researchers, NGOs, and aid organizations have committed lots of funds and knowledge production in terms of framing the water issues in Palestine while also providing solutions. However, those solutions never actually challenge Israel’s water policies in the West Bank. For example, instead of holding Israel accountable for all the demolitions of the very infrastructure that these international aid organizations have funded, these organizations come in to mend the infrastructure. So it’s really important to speak about who controls the narrative, because it’s not only about who controls the water.

SP: In light of this humanitarian solutionism being so reliant on technology rather than political demands, it seems relevant that Israel brands itself as a tech capital. Water technology is a major part of Israel’s nation-building project, from its aspirations of “making the desert bloom,” to its pride in exporting desalinated water to neighboring countries like Jordan. Israel starves Palestinians of water with one hand, and exports it with the other. How does this benefit its global image?

MD: Since its creation, Israel has promoted itself as a modernization project. The idea that Israel is coming to these desolate, undeveloped environments to make them flourish fits into a colonial logic that different colonial powers have used to exploit and erase indigenous presence on the land. When Israel promotes itself as a leader in environmental technologies, it exports not only technology, but also the techniques for governing colonized people. For example, their projects that travel to other places around the world lead to a higher level of privatization of water resources, and higher levels of exclusion of colonized people from their resource development, while ensuring a state hegemony over these resources in those places. For this export to happen, Palestinians must first live with manufactured thirst and manufactured scarcity of resources. Technology doesn’t really move apolitically.

Israel also pushes its narrative in the climate change arena. With Noura Alkhalili and Yahia Mahmoud, I’ve recently written a paper on the enduring colonialism of ecological modernization, looking at how cases like the occupied Golan Heights and the Moroccan-occupied Sahara became sites of green colonialism. While these populations are denied their basic rights to self-determination, Israel and Morocco are promoting themselves as innovators of solutions to combat climate change, and they’re treated by the international community as regular nation states that are doing their best to combat carbon emissions. But those wind projects are happening on occupied land, and the water conservation technologies that Israel has been promoting and exporting have been taking away resources from Indigenous communities. All of these projects need to be exposed for what they are. This is part of a larger dynamic of an enduring and continuing coloniality that we are witnessing everywhere around the world.

SP: Water scarcity results in a variety of consequences for Palestinian life, ranging from environmental degradation, to health issues, and economic impacts. Of course, these manifest differently for Bedouin communities, for farmers, and for those in cities. To what degree are water rights part of the political consciousness in Palestine, and how do people work across these differences in experience?

MD: Water has been at the forefront of a lot of civil society work and advocacy in Palestine for very long, and that work highlights how water injustice is actually orchestrated. The Palestinian Authority and international NGOs take a utilitarian approach, focusing more on just making sure that we get enough water, even if it means paying Israel an even higher price for the water underneath our feet. But because of their political consciousness and lived experience, most Palestinians would say, “If I have water, that doesn’t mean I’ll stop demanding water rights. Water rights are much more than that. We have the right to resources. We have the right to our springs. We have the right to know our water and to be on the water as well. It goes beyond how much water we get.” That means reclaiming rights to their water to practice sustainable agriculture on their land, and to carry out water projects that they know are the best approach to a sustainable existence. This has been happening for decades in Palestine through grassroots organizations and agricultural collectives. This has been part of the political consciousness of Palestinians for a long time, through this idea of sumud: how you stay on the land is through a connection to the elements.

SP: You’ve talked about the pitfalls of mainstream humanitarianism, which has largely legitimized Israel’s occupation. What frameworks of solidarity in Palestine and abroad are necessary to support Palestinian self-determination, through water rights and beyond?

MD: In most of today’s economies where we find Indigenous communities, marginalized communities and struggles similar to that of Palestinians, though maybe under different conditions – for example, state violence in Latin America – the networks of solidarity are extensive and have been there for a long time, but now they’ve become even more necessary and critical. Palestinian activists and farmers are connected with different campaigns in North America, for example, that are facing the same kind of water injustices and climate injustices. Many established networks like La Via Campesina center Palestine in all of their work very vocally. And I think because of the urgency of the current moment of genocide, and the magnitude of environmental catastrophes that have been happening in Palestine, we need to make sure that we accelerate that solidarity and make it very visible.

There are many Palestinian grassroots organizations, for example the Union of Agricultural Work Committees, that center land, water, farmers’ liberation and farmers’ sovereignty over their resources at the heart of the work they do. This moves us toward achieving food and resource sovereignty in Palestine. A more explicit water justice framing reveals the role of the IT industry, tech companies and multinational water service providers in perpetuating water injustice. This could bring out networks of solidarity that maybe haven’t been visible or haven’t been tapped into already. We should also confront the sites where domination, extractivism, and theft of resources are clearly happening and are being exported elsewhere. I think this is the moment when this type of work is necessary. It can make the difference that we all want and strive to see.

Dr. Muna Dajani is an action researcher with a background in critical political ecology. Her work aims to understand environmental and water governance through decolonial and critical lenses. She holds a PhD from the Department of Geography and Environment at the London School of Economics (LSE). Her doctoral research focused on examining community struggles for rights to water and land resources in settler colonial contexts in Palestine and the occupied Syrian Golan Heights, with special attention to how farming practices acquire political subjectivity.