“We have to specify something!” An exasperated partner at a well-known design firm said to me recently.

The material at issue? Synthetic flooring.

Inescapable, ubiquitous, unsexy: flooring lacks even the marquee presence of wall and ceiling finishes, with which it shares “minor” status among architectural components (as much as any multi-hundred billion dollar industry can be said to have “minor status”). A challenge that responsible design workers face is that the flooring most commonly specified for construction and renovation projects is not wood or stone or tile, but carpet, or, to an increasing degree, resilient tile, types of flooring that are made nearly exclusively out of plastic.

That “tracks”, as they say. After all, if steel and coal epitomized the high water mark of industrial capitalism, then plastic and petroleum are surely the substances that most fittingly represent the amorphous and pervasive quality of its present late stage. For Roland Barthes, writing about the material in his famous essay series Mythologies, plastic embodies mutability and ephemerality: “more than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation… it is less a thing than the trace of a movement.” But this movement that is contained in plastic also has another sense for Barthes: namely, its historical trajectory would prove both transformative and spatially expansive, “the whole world can be plasticized . . .” he concludes.

By any measure, much of has been. The amount of plastic produced worldwide, which was less than two metric tons around the time Barthes wrote “Plastics”, now exceeds 430 metric tons, a not insignificant portion of which (as much as 20%) has been consumed in some way by the building industry. Among plastic products, carpet contributes disproportionately to waste streams due to its relatively short lifespan, and the relatively frequent turnover of interior space compared to core and shell building components.

Somehow it has become normal that upon much of the world’s firmament has been applied petroleum-based resilient vinyl surfacing or 12 or 15-foot loom-widths of nylon broadcloth, heat-seamed ad infinitum, apparently in every direction. Only a small proportion of carpet uses natural fiber such as wool. The rest, roughly one billion square meters produced yearly, is made from synthetic polymer fiber. Synthetic carpet is not the only flooring made of plastic, however. Other forms include epoxy terrazzo which can be poured, or installed as tiles or slabs. Composite wood floor planks can comprise laminates having plastic coatings, or can be impregnated with phenolic resin. Additionally, the building industry consumes 69% of polyvinyl chloride produced worldwide, much of it in the form of vinyl flooring, which is the fastest-growing flooring type, having surpassed yearly production of carpet of all types.

One major manufacturer of synthetic carpet and vinyl tile is Milliken & Co., a privately held American company well-known among interior design and procurement workers who specify large amounts of commercial carpet and resilient flooring. A close examination of Milliken & Co. reveals a common two-pronged strategy among building product companies: at once promoting itself to the public and the design industry as proactively leading sustainability efforts, while at the same time advocating against climate policy to protect their financial interests. It reveals, too, how design and procurement workers are manipulated to act in the interest of these industries, and how the U.S.’s primary professional architectural membership organization, the American Institute of Architects (AIA), has been enlisted in the process.

A modest tradition of logrolling between the AIA and Milliken & Co. can be traced back to 1992 when the AIA awarded Milliken’s long-time company president Roger Milliken honorary membership (the highest honor it can bestow upon a non-architect), at the urging of a small group of architects from his home state of South Carolina, who had long enjoyed Milliken’s patronage. Milliken at the time was a powerful figure in the Southern coastal U.S: a wealthy textile magnate and Republican Party kingpin known for, among other things, union-busting and for his staunch support of deregulatory policy. By 2022, under new leadership, Milliken’s relationship with the AIA had evolved, culminating in its signing on as a corporate partner in the AIA’s Committee on the Environment (COTE), a climate initiative the AIA had begun in 1990.

On the face of it, Milliken seems like a model partner in COTE’s mission “to achieve climate action and climate justice through design.” Milliken prides itself on having been a “steward of the environment for… more than 100 years.” The company’s leafy website and yearly sustainability reports chart its path to achieving zero emissions by 2050. As detailed in a report by carpet industry lobbyist Robert Peoples of the Carpet and Rug Institute and Carpet America Recovery Effort, Milliken has kept pace with reforms across the carpet industry by significantly improving efficiency across a range of measures including reducing energy and water use, reducing CO2 and hazardous air pollutant emissions, and reducing manufacturing waste. Like its competitors, Milliken instituted an ambitious carpet landfill diversion program and has eliminated hazardous PFAS chemicals from its products, in advance of legislation compelling them to do so. Like its competitors, Milliken “dematerialized” its product (reducing its mass) and incorporated recycled fiber in its nylon broadloom carpets and modular carpet tiles (derived from recycled carpet and other sources). Further, Milliken complies with a host of rigorous reporting protocols overseen by third-party accrediting bodies.

Milliken’s most highly-publicized claim, however, is that its premier building products, nylon carpets, and vinyl tiles, are “carbon neutral everywhere in the world.” In other words, through these reforms, it has supposedly reduced the net emissions resulting from the fabrication of their flooring products to zero.

That’s impressive for what are, after all, petrochemical products.

Nearly all carpet is synthetic, and while plastic can be derived from nearly any organic substance, including vegetable oil, straw, woodchips, soybeans, or recycled food waste, virtually all plastic is produced from one type only: petrochemical feedstock originating from fossil fuel; that is, coal, petroleum (crude oil) or natural gas (we’ll get to the reason for this shortly).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, promoting these products as “carbon neutral” requires some math, specifically, the subtraction of carbon offset credits from the total of actual emissions generated in production cycles. Unfortunately for the very many corporations such as Milliken who include credits in their emissions accounting, investigators have found that the majority (upwards of 94%) of the credits certified by the company issuing those credits (Verra, the world’s largest carbon credit administering body) either fail to provide what’s known as “additionality” (the concept that emissions credits can only be considered reductive if the actions taken wouldn’t have happened otherwise) or were found to be altogether fraudulent. Milliken, a multibillion-dollar company with sales in 135 countries, 70 plants and offices, and over 8,000 employees, has yet to clarify its copy at the time of writing.

Added to these prevarications are a further host of questionable accreditations, jerk-off awards, and middling public philanthropy. Completing this media portfolio, is the dissemination of research and advocacy that obscures industry sponsorship, blurring the line between private and public interest (take for instance the volume Recycling in Textiles, where the above-mentioned Robert Peoples report was published, which sets research funded by the industry trade group, the Carpet Research Institute, alongside university-based research). Of growing importance in this respect is the influence of trade organizations in formulating Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) which are the technical reports companies voluntarily provide to back up sustainability claims. As detailed in the Center for Environmental Health’s 2022 report “Flooring’s Dirty Climate Secret” certain data used across a number of vinyl flooring fabricators in formulating EPDs, drastically underestimates emissions generated in their production.

Milliken’s drive to portray itself as sustainable serves a function beyond merely selling commercial floor covering. More specifically, they are meant to manage how a particular type of product is perceived by various stakeholders whose participation is essential to sustaining Milliken’s sales: design workers, builders, clients, purchasing agents, building product company workers, and retail customers. From a business perspective, what matters to companies like Milliken, is that their products continue to be produced and consumed within a greening economy. Economically, it matters less whether their products actually are sustainable, so long as they are used as though they are.

The capture of climate discourse by corporations exceeds “greenwash”. It signals a new unhappy phase of enhanced disciplining of workers and consumers worldwide, one whose Orwellian dictum is “Oil = Environmentalism”. It does more than obfuscate climate damage, it performs the remarkable trick of capitalist recuperation, on the one hand delimiting and defanging political resistance, while on the other creating space for the growth of new products and services, expanding both spatially, and intensively, enmeshing subjects ever more completely.

For much of the building product industry, the participation of design and procurement workers is essential for generating revenue. Structurally, they facilitate distribution by connecting clients, often large corporate or institutional buyers, with the building products that fabricators provide. Ideologically, they impart an aura of legitimacy and professional accreditation to the products they specify due to their reputation for being well-educated and climate conscious. Passing through this gateway innumerable times cleanses products, diffuses accountability, and habituates stakeholders to their normalcy and acceptability. Milliken’s partnership with the AIA further imparts the blessing of professional legitimacy to its building products while targeting its marketing to a focused, incentivized customer pool of architectural workers, a good proportion of whom are AIA members.

Building products embody historical information accrued throughout their development. Such information comprises products’ fabrication, provenance, affordances, and use. Inheriting these products, designers inherit hosts of factors defining and limiting design agency. This inheritance includes the inertial force of these products flowing throughout the production/consumption cycle. For “Oil=Environmentalism” to be true it doesn’t require the brainwashing effect of a totalizing ideology per se. What’s sufficient is that the statement be treated as if it were true. It requires a combination of just enough muddying of the waters, and just enough structural discipline to ensure stakeholders’ material participation. It requires neither wholesale brainwashing nor wholesale servitude. It requires only that stakeholders be subject to just enough job insecurity, just enough time pressure, just enough budget and program restrictions, and just enough lack of product alternatives. Most of all it requires that the churning treadmill not slow down. It requires, simply put, that “we have to specify something!”

“All architects may unwittingly be working on the same building”, wrote Rem Koolhaas, in a parenthetical aside on air conditioning and in his seminal essay “Junkspace”. He was responding to the consistent smooth texture encountered throughout contemporary designed space, but he could have just as easily been talking about plastic. Plastic seeps across poorly formed space like kudzu, terminating arbitrarily, reflecting neither spatial hierarchy nor human scale or presence. The spread of plastic flooring reflects the spatial expression of cheap, plentiful oil, seeping its way across our vast acreages of carpeted showrooms, conference centers, hotel ballrooms and lobbies, air-conditioned corridors, cubicle farms, hospital waiting rooms, and airports.

Barthes’s prescient observation that “the whole world can be plasticized”, isn’t meant to highlight, much less lament, the substitution of fake materials for authentic ones, but rather the wholesale recasting of material reality under capitalism, its capacity for creating new affordances and new subject positions, incentivizing and disciplining behavior at every turn (such recasting is neatly summarized by Susan Freinkel’s observation in Plastic: A Toxic Love Story that the U.S. interstate highway system grew in line with the disappearance of the looped reuse of glass bottles). The media barrage created by companies such as Milliken, achieves discursively what the transformation of material reality achieves disciplinarily, namely to position and enmesh subjects ever more inextricably within the logic of petro-capitalism.

Milliken’s propaganda campaign extends far beyond buyers and specifiers of flooring. Behind closed doors and behind industry-front organizations, Milliken has persistently contributed to systemic attempts to influence legislation, in order to advance its own economic interests and in opposition to widespread policy consensus. And while its reforms match those of its competitors, it does stand apart from them in one significant way, as we will see.

Through the looking glass of ethical capitalism, it is perfectly normal for the fight against plastic waste to be led by the PR departments of plastic fabricators. Surpassing Mark Fisher’s observation that “climate change and the threat of resource-depletion are not being repressed so much as incorporated into advertising and marketing”, polluters now crowd the stage, proclaiming themselves exclusively positioned to fix it. A common form this takes is a type of astroturfing that activists have termed greencrowding which is when companies form coalitions that masquerade as public advocacy organizations, but whose true purpose is to redirect attention away from the core activities of the industry. One prominent example is the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW), founded in 2019 under the direction of the American Chemistry Council, by a coalition of major oil companies (ExxonMobil, Shell), plastic producers (Dow, BASF, Formosa), and some of the world’s largest producers of single-use plastic packaging (P&G, PepsiCo). As AEPW’s membership roster helpfully maps out, the fossil fuel, petrochemical, and consumer plastic industries (let’s abbreviate them to “FFP&P” henceforth) are closely aligned, forming interconnected supply and production networks that often lobby as a political bloc.

Among the AEPW’s member companies appears a single building product provider: Milliken.

Milliken appears again, alone among interior furnishings companies, on the membership roster of a similar not-for-profit, The Recycling Partnership alongside a similar but wider list of petroleum (ExxonMobile), chemical (Dow, Eastman), and consumer goods (Coca-Cola, Mondelez) companies and industry lobbyists.

Corporate membership webpage of non-for-profit The Recycling Partnership. Screenshot, cropped, with collage by author. In a 2022 press release, The Recycling Partnership proposes a $17B government-funded campaign “pairing behavioral science with programs aimed at growing access (to recycling sites).”

Milliken is not even among the top ten largest international flooring companies nor even in the top ten interior furnishings companies or building supply companies. So why is it the only representative of these categories in the AEPW and The Recycling Partnership? The reason is that, unlike other flooring giants, Milliken isn’t just a fabricator of carpet and tile that uses synthetic fiber and vinyl but is itself a petrochemical company, for which synthetic flooring provides a market to sell the petrochemical-based material it produces.

Originating in the 1860s as a small purveyor of woolen goods, Milliken grew into a major textile company through the acquisition of smaller, struggling mills throughout the southeastern U.S. in the first half of the 20th century. During the Second World War, the plastics industry was enlisted to develop substitutes for countless materials that were in short supply or unavailable. Japan’s incursions into Southeast Asia in late 1941 cut off access to natural materials including silk from Singapore needed for tire cord and parachutes. In response, the U.S. government awarded commissions to certain textile manufacturers, Milliken among them, to boost production of nylon, the use for which was later expanded to glider tow ropes, aircraft fuel tanks, flak jackets, shoelaces, mosquito netting, and hammocks. Wartime investment, as Jeffrey L. Meikle has detailed in his book American Plastic, transformed plastics fabrication–which up to that point, provided mostly incidental items that were promoted as low-cost substitutes for natural materials–into a major industry, quadrupling production between 1940 and 1945.

The popularity of synthetic fabrics in the civilian economy after the war led Milliken to phase out natural fibers from its product lines altogether. But what likely incentivized Milliken, too, was the need to quell growing labor power and unrest in the years immediately following the war. Compared to producing textiles from natural fiber, producing synthetic textiles required more machines and less labor. This reduced workers’ leverage to bargain at a time when they were already struggling to preserve gains won during the Depression-era New Deal and the War. Expertise once held by weavers in the textile industry, and subsequently by loom operators was increasingly superseded by chemical engineers whose work was more subject to the managerial control of owners. In 1963, Milliken began to test vertical integration, opening and operating a single chemical factory. Throughout the late 1980s, Milliken began acquiring chemical companies, expanding its range of products and market share.

Today the company fabricates and processes thousands of chemical products, in addition to the synthetic fibers—exclusively nylon—used in its carpets, and polyvinyl chloride, used in its floor tiles. This links its fate with that of upstream fossil fuel and chemical feedstock suppliers, and downstream, to its customers in the plastics, industrial product, and building industries, not to mention the marketing and regulatory environments it navigates and makes considerable effort to manipulate.

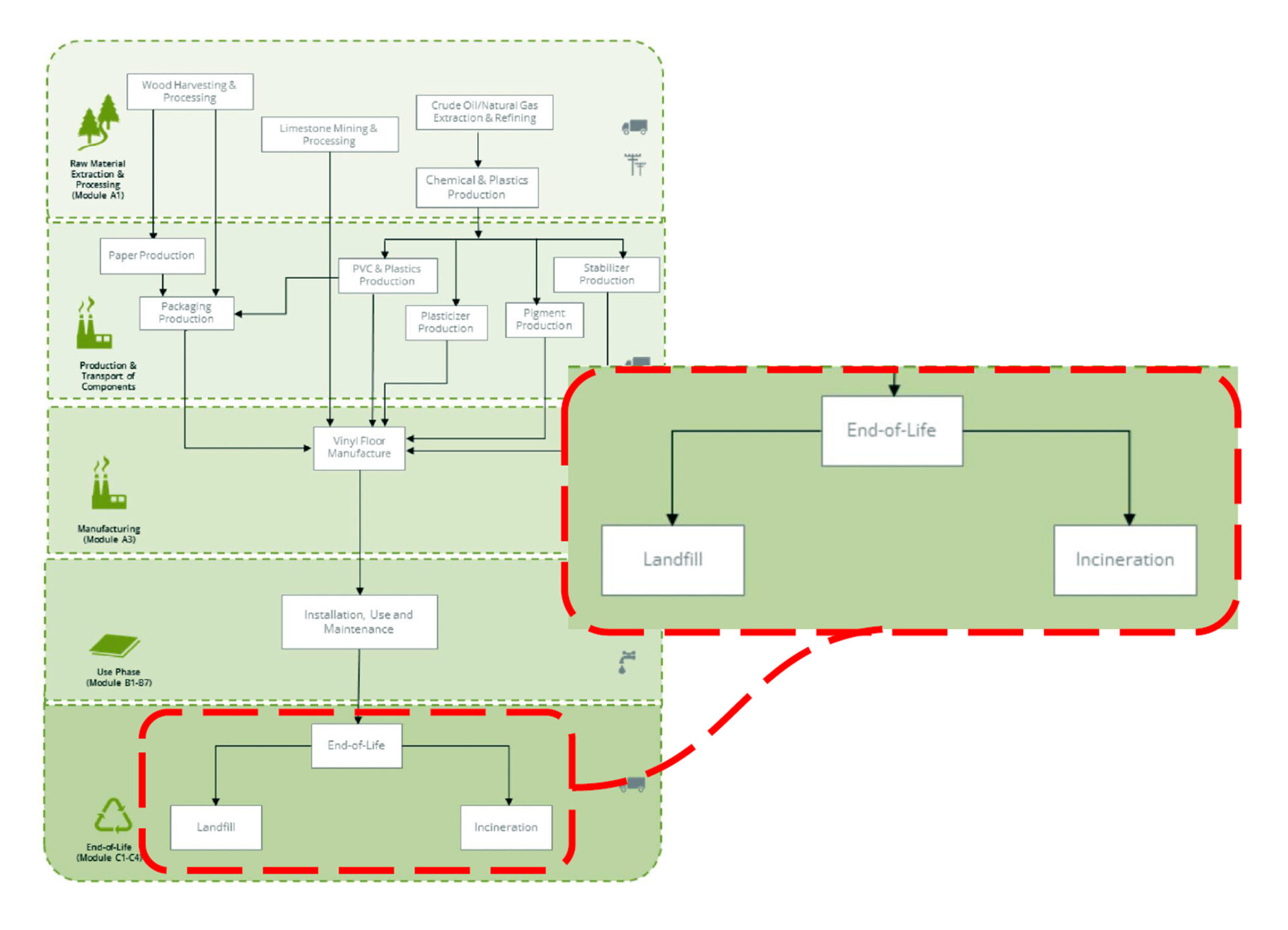

Like many corporations, Milliken promotes “recycling” to propagate an impression of voluntary corporate self-governance. Among Milliken’s claims is that its synthetic flooring products are “100% recyclable”, which is technically true, but misleading. At present 9.2% of carpet is recycled in the U.S (a figure which reduces further when California’s mandatory carpet recycling program is discounted; the U.S. national average is 3%). The rest finds its way to landfills or incineration (the latter of which is often rebranded as “waste-to-energy”, and sometimes considered by industry to be a form of recycling).

Recycling is subject to leakage of various kinds and degrees across a range of measures and systems and at every stage of a product’s lifecycle. This includes the dissipation of embodied energy (as when carpets are downcycled into less valuable materials such as insulation), the loss and contamination of material associated with gathering, separating, sorting, and reprocessing as well as the release of toxins, and the displacement of environmental degradation, connected with landfilling and incineration, and, as is becoming widely recognized, the dispersion of ever finer particles, newly discovered at the farthest reaches of the atmosphere and ocean depths, and in human blood and placenta. While the goal of a circular economy is to eliminate such leakage, in the meantime, capitalism weaponizes entropy as externalized costs are dispersed across space and time.

All types of synthetic carpet fiber are recyclable. But even under ideal conditions, all degrade with each iteration and ultimately become unusable. As such, recycling doesn’t eliminate disposal into the waste stream, it delays it. One increasingly widespread example is the marketing of carpet fiber containing negligible amounts of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) from recycled bottles. Unlike nylon, which it increasingly replaces in the market, PET polyester recycled from carpet has little or no value. In fact, recycling companies have cited its increasing presence in recycling bales as a decisive factor in preventing their industry from gaining an economic foothold.

Synthetic carpets, like many other building assemblies, such as insulated wall and roofing panels, comprise plastic sandwiches of a kind: hybrid assemblies of different types of plastics or other materials laminated, coextruded, or otherwise inseparably fused. While some of these can comprise disassemblable systems such as interior office partition systems, raised flooring systems, and certain insulated panel systems, agglomeration tends to obviate plastic recycling condemning most hybrid components to landfill. More recently, the plastics industry has shifted to promoting “chemical-” or “advanced recycling” which, it claims, bypasses the need to separate mixed plastics. According to a recent UN report, scientists disagree, considering these processes little more than repackaged incineration: “The science and data . . . point to the conclusion that chemical recycling would support expansion of plastic production, while potentially causing unacceptable levels of environmental and social harm — as well as impacts on human health — through emissions, waste generation, energy consumption, and contaminated outputs.”

Other plastic building products–some carpets, vinyl tile, vinyl wall covering, solid surfacing, plastic laminate, fiber-reinforced polymer panels, and spray-on foams–are adhered on-site, rather than mechanically fastened. Synthetic carpet fibers are fused to rigid backing and can consist of two or more synthetic yarns twisted together or with natural fibers. Further complicating recycling, is that plastic typically contains toxic additives often difficult to separate out and dispose of. All of these physical factors have prevented recycling’s widespread adoption, but they are not the main factor, as we will see.

Recycling serves a crucial ideological function for plastics companies. It is the primary rhetorical tool they employ to deflect, delay and obscure accountability for the deleterious effects of plastic production and waste. The plastics industry’s decades-long disinformation campaign to promote recycling while its own research showed it to be economically unfeasible, is increasingly well-documented. Pivoting its message throughout its expansion, the industry’s original mission to persuade consumers to “love plastic” transformed upon market saturation into the need to acclimate the public (some for whom memories of material rationing still lingered) to throw plastic in the bin. With the innovation of planned disposability, plastic’s status as waste became prefigured in its fabrication. Eventually of course, producers became increasingly unable to credibly deny the problem of discarded plastic accumulating over decades. What they could do, in the face of what has become a global waste stream now exceeding seven billion metric tons of plastic garbage, was flood the mediascape with solutions that work for them, which is to say, solutions that redirect focus from the obvious step of curtailing production, to downstream, consumer-focused measures. The AEPW’s campaign follows this script closely, directing its $1.5 billion war chest towards promoting recycling and “consumer education” (if you think that sounds like encouraging people to pick up garbage, then, you’d be right).

The FFP&P industry’s effort to manufacture consent among the public, however, is secondary to its primary goal, which is to influence legislation. For this it channels massive funds towards more neutral-sounding industry front organizations, the most powerful of which is the aforementioned American Chemistry Council (ACC), one of the largest spending lobby groups in the US, (and onto whose board the president of Milliken Chemical, a subsidiary of Milliken & Co., has recently been appointed).

The ACC’s record leaves little doubt as to its position on climate regulation. Criticized for contributing to organizations promoting climate denialism, the ACC was instrumental in lifting bans on offshore drilling and extraction on public lands. It opposed designating GHGs as pollutants under the Clean Air Act, and has led state-by-state efforts to preemptively illegalize plastic bags bans nationwide, and has supported a Wisconsin bill which criminalizes demonstrating on the property of energy providers. Currently, although claiming to support a robust plastics reduction treaty now being negotiated by UN member states, the ACC has fought to weaken, delay, and redirect the treaty’s focus towards “circularity” and other industry-friendly solutions. Meanwhile, between 2007 and 2019, global investment in the petrochemical industry more than doubled, including new factories to crack ethane and produce plastic for consumer markets. Members of the AEPW alone invested $186 billion into new petrochemical and plastic production facilities between 2010 and 2017.

The ACC’s efforts are illustrative of the FFP&P industry’s recent pivot in its strategy and messaging. Facing drastic declines in energy and transportation sectors as economies transition to renewable energy and electric vehicles, the oil industry, and oil-producing countries, have turned to petrochemicals, and the plastic markets they feed, to provide a crucial lifeline for the industry. At present, that means sopping up overproduction of shale natural gas. In its rush to avoid stranding fossil fuel assets, the FFP&P industry plans to nearly double production of petrochemical feedstocks for plastic in a decade, and triple it by 2060. Such expansion, however, may be as futile as it is harmful. To begin with, petrochemicals comprise only 9-10% of global fossil fuel production, far too small to make up for predicted declines in heating and transportation sectors. Moreover, worldwide plastic production already far exceeds demand, which is also slowing. To absorb overcapacity, companies have expanded consumer markets in developing countries. After China’s 2019 restriction on recycling imports, waste exports shifted to Africa, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, typically finding their way to poorer regions that lack minimum solid waste disposal infrastructure and enforcement over illegal dumping and incineration. The subsequent refusal, in recent years, of these nations to import plastic waste has seen plastic recycling rates fall in countries such as the US from 9% to a current rate, experts estimate, of 5-6%.

Disgraced and distrusted from birth, plastic became accepted by consumers for its utility and accessibility. Its indisputable value, however, has been appropriated by a larcenous corporate class, compelled to displace costs to weaker nations, to fenceline constituencies (according to a Greenpeace report, approximately 80% of waste incinerators are located in low-income communities or communities of color), to taxpayers, and to future generations. As long as the FFP&P industry continues to extract massive profits, it can be expected to fight off climate-driven restrictions on plastic production for as long as possible, to obstruct steps that scientists insist are necessary to mitigate climate catastrophe, and to delay the work of remediating the damage done.

For its part, the AIA will doubtlessly continue to advocate for climate reform within the industry. The new AIA is scrupulously politically correct: presenting publicly as an organization that is as socially progressive as its older incarnations were genteel and paternalistic. Promising change, its incoming young leadership may (and should) break ties with corporate polluters and manipulators such as Milliken (as it quietly did with Kingspan in 2022). Such shoring-up of its brand may prove ever more frantic for the AIA as it contorts itself trying to resolve its fundamental, ever more apparent, internal contradiction: which is to presume to serve both capital and labor, whose interests around climate do not align. Far less likely would be for the AIA to commit to sustained, principled support of the former if it entailed antagonizing the latter. For that, design and procurement workers need unions.

More consequential, therefore, will be for designers and procurement workers to begin to refuse to just “specify something” through organized and individual acts of protest. Soon, they may start looking beyond the AIA for the support and representation to do so.