Last year, the British Conservative government launched a national commission called ‘Building Better, Building Beautiful’, which sought to advocate for beauty in the built environment. According to its interim report Making Space for Beauty, the commission is adamant that its role is not to dictate architectural style. But the report’s unambiguous criticism of “what went wrong in the twentieth century”, its praise of “fine” and “beautiful” house building in the Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian eras, and the government’s decision to hire long-term champion of traditionalist architecture Roger Scruton as chair of the commission should leave us under no illusions as to its priorities.

Today, this traditionalist tendency is gaining renewed momentum in various corners of the European Right. In the Netherlands, far-right nationalist politician Thierry Baudet frequently derides the “ugly architecture” that is, in his mind, corrupting Dutch society. And in Germany, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party has spawned a movement of revivalist architecture by individual practitioners obsessed with Saxon mythology and pitted ideologically against the metropolitan built environment. Amid the rising tide of populism in Europe, Western chauvinists and white supremacists are attempting to re-valorise traditional Western architecture in order to advance their reactionary and exclusive politics.

There is clearly a reaction taking place against modern architecture, led by conservative voices and members of the New Right. In lieu of the myriad contributions of modern architecture, we are offered fantastical mythological incarnations, or more commonly, a revived neo-classicism as a conservative alternative. But what drives those on the Right to their critique, and what are their self-enacted solutions?

The motley crew of right-wing architecture critics owes much to the work of Roger Scruton. Scruton positions himself as part of an older conservative philosophical tradition and a stalwart supporter of all things traditional. His gentlemanly demeanour is frequently played up by the British media, including the BBC, who allowed him to host the documentary Why Beauty Matters in 2009. In the documentary, Scruton repeatedly refers to the “crime of modern architecture”, and in one scene argues sardonically that the architects of a dilapidated office block were as much vandals as those who later graffiti-tagged the place. The argument of the documentary more polemically restates the general thesis of his 1979 book The Classical Vernacular: Architectural Principles in the Age of Nihilism — where “nihilism” may as well be an indeterminate synonym for “left-wing”. Here, Scruton argues that architecture lost its way somewhere in the early 20th century by attempting to forge a new aesthetic style less dependent on classical and gothic features.

Scruton’s considerable influence has been picked up by a host of right-wing exponents since the philosopher’s foray into architectural criticism. “Why is modernist and postmodernist architecture so grotesque?” is, for example, the leading question by YouTube charlatan Paul Joseph Watson in one of his typically incendiary videos entitled Why Modern Architecture SUCKS. We are in any case not offered much of an answer besides a bunch of scattered aphorisms: “good or bad architecture can lift or subdue the human spirit’ and ‘aesthetic ugliness encourages ugly behaviour”.

Such rhetoric also infects the discourse of Baudet in the Netherlands. He uses the term “oikophobia“ to denote how a supranational elite of architects, designers and Eurocrats have allegedly turned away from all things considered homegrown in order to undermine, consciously and unconsciously, the foundations of the nation-state. “Modernism, multiculturalism and the European project”, he says, “enforce an alienating living environment… A world without a home.” Racism pervades Baudet’s worldview, where “gargantuan tower blocks with satellite dishes directed towards Al Jazeera“ become a poignant symbol of the sickening aversion to “our own” habits, the nation, and the beauty of traditional arts and architecture.

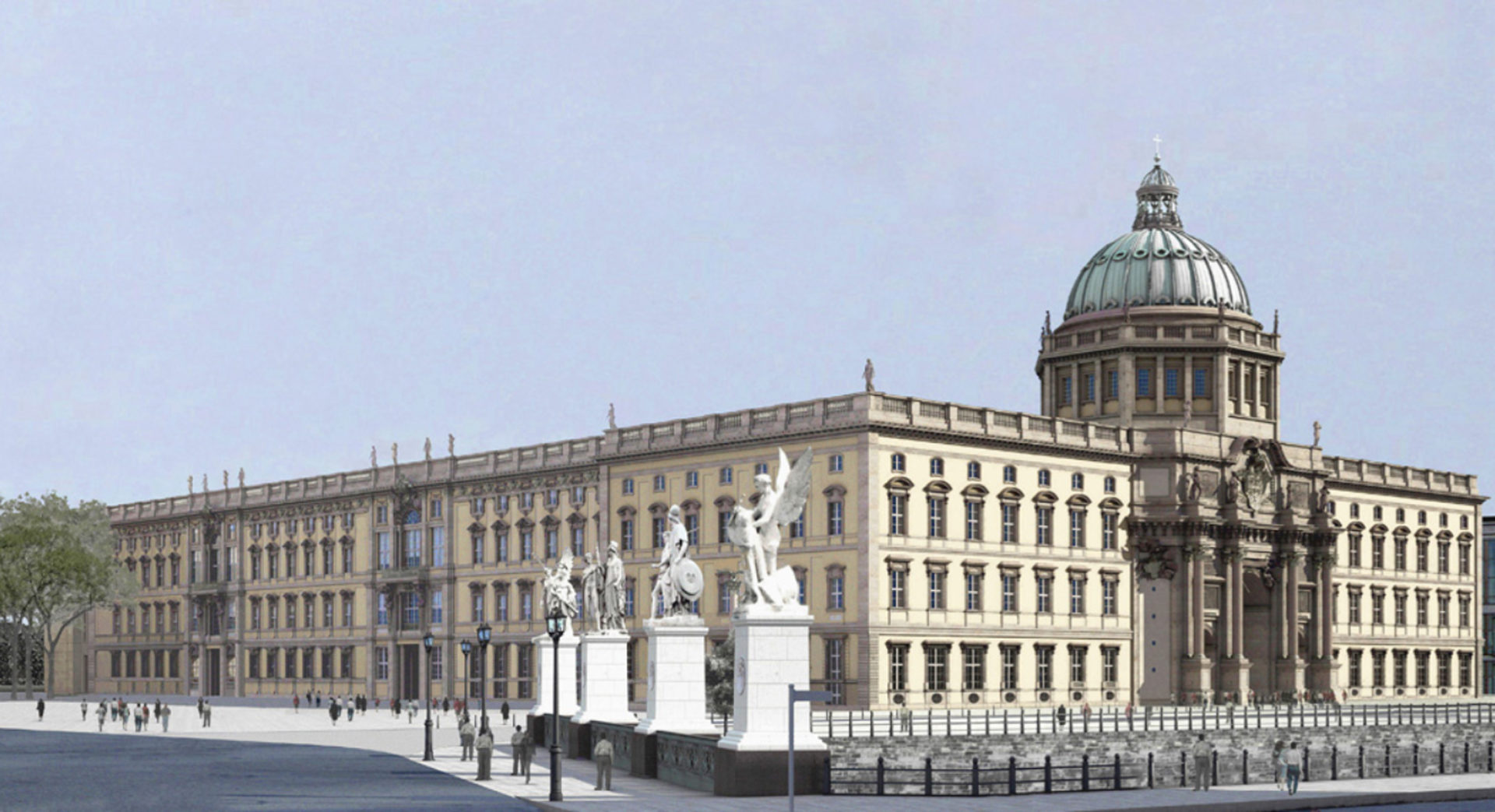

In Germany, right-wing reactionary architectural practice takes place on varying planes of intensity. Take for instance the Berlin Palace. Originally built in the baroque style in 1845, it was demolished in the 1950s by the German Democratic Republic to make way for the typically modernist Palace of the Republic in the 1970s. This was in turn demolished in 2008 to make way for a reconstruction of the original palace, due to open this year. At the more extreme end, some followers of the AfD have taken architectural practice into their own hands, restoring and erecting structures in the rural east that seek to counter the “death of the Volk”.

Architecture in Poundbury, United Kingdom.

Alex Liivet/Flickr

Scruton’s appeal to these subversive movements — as can be seen, for instance, in this discussion between the philosopher and Thierry Baudet — is that he offers a counterposing set of architectural principles by which to judge architecture. His ideal is the ‘practical’ aesthetic, which is grounded in the spectator’s concrete experience of a building rather than adherence to a top-down, abstract design on the part of a planner or architect. While it’s not a bad thing per se to argue for more public involvement in the design process, for Scruton this conception without fail gravitates toward one solution: a revived traditionalism perhaps best exemplified by Poundbury, an experimental new town in South West England initiated by Prince Charles and also incidentally one of the towns that Paul Joseph Watson exhorts us to praise at the end of his puff-piece.

Baudet’s solution comes across as equally superficial: a return to the forms and styles of a time when Western civilisation was still allegedly producing great architecture. In other words: Rem Koolhaas and Rotterdam bad, Rob Krier and Paris good. In a similar manner, the AfD influencer Claus Wolfschlag has pleaded for a “volkisch” reconstruction of German city centres eradicated by allied bombardments during the Second World War.

These threads of right-wing critique form the front that critics use to try to smother modernist architecture, with all its ostensible left-wing and cosmopolitan pretensions. But more than that, the critique also anticipates what Americans have come to call the “culture war”. After his appointment to the commission, Scruton provocatively remarked, “Whether or not this is inciting a culture war I do not know.” His appointment is thus articulated ambivalently: it may not be an incitement to war, but at the same time, it very much could be. By leaving the idea hanging, he opens a new front in any supposed war, accepting no responsibility himself but leaving his supporters to take-up the fight.

The aim of the architectural aspect of such a war is to herald a ‘return’ to aesthetic order. This can mean two things. On the more moderate edge, the ‘return’ signifies the aesthetic move to a bygone era that divorces a building from its social context. This is visible in how Scruton’s commission suggests that the housing crisis is a problem solely of aesthetics, and that we can house more people if we build in an architectural vernacular more accustomed to a specifically-conceived ‘public’. This is a ridiculous claim, which ignores the bigger, structural problems of land, wealth, inequality and systemic oppression and exploitation that right-wing governments of the day at best wish not to address and at worst actively encourage.

On the more extreme edge, however, the ‘return’ forms part of a white supremacist project which is attempting to redefine the meaning of citizenship and identity. Perhaps the most well-known and prolific social media outlets to vent such ideas are the @Arch_Revival_ and @MagicalEurope accounts, both of which appear on a list of “5 Twitter Accounts That Will Make You Proud to be European“, published by far-right website Defend Europa. By divorcing architecture from its grounding in social life, such sites are able to portray Greek and Roman architectural forms, for instance, as representing a racially-pure European society. These architectural styles supposedly reflect the protection of a nativist social order that looks after its white citizens only. Aestheticised architecture becomes, for the New Right, a means of impulsively declaring things good or bad: if traditional architecture encourages virtuous behaviour, modernist architecture encourages degeneracy.

On this note, it’s telling that Scruton was eventually sacked from the Building Better, Building Beautiful commission (albeit then later reinstated) for racist remarks he made in an interview with the New Statesman’s George Eaton, who recorded Scruton as saying, among other things, that Chinese people were replicas of each other, and that there was an “invasion of huge tribes of Muslims” into Hungary. It is easier still to spot the racism that underpins Watson’s arguments, a simple skim through his YouTube page is revealing, or to realise the inherent dog-whistle in Baudet’s statement about television satellites and Al Jazeera, which he associates with the modernist expansion schemes on the fringes of Dutch cities.

The proposal of Baudet and other right-wing thinkers to return to vernacular building traditions is as historically ill-informed as it is deplorable. This comes across in the form of basic errors. Watson, for instance, makes no distinction between the opposing styles of modernism and postmodernism. It also manifests in their lack of understanding of why the traditionalist style they favour took hold in the first place. During the nineteenth century, neoclassical, gothic and renaissance styles frequently masked the squalid living conditions and poor construction quality of newly-erected tenement houses in Europe’s industrial cities. Meanwhile, in places like Paris, the introduction of grand, classically-influenced architecture to the city’s centres was predicated on the displacement of millions of working-class people, and the destruction of centuries-old medieval buildings, much to the chagrin of contemporary conservationists.

Context is also neglected when the proponents of the neo-vernacular blame a style and its figureheads for the failure of modernism. During the 1950s and 1960s, when urban modernism reached its zenith, booming population numbers pressured governments into building huge quantities of housing while money-grubbing construction companies took advantage of the situation by building ever more shoddy housing. Rightist criticism of architectural modernism tends to focus on what it sees as the visually offensive products of ‘socialist’ post-war housing. They carefully choose to ignore the fact that the most visually insistent manifestations of post-war modernism are the fruits of capitalist enterprise in post-war mixed economies, in which conservative governments often took the lead.

These oversights may all seem relatively inconsequential. However, they are in fact part of a coordinated attempt to obscure the real problems that have long plagued contemporary society. What is at stake is the erasure of an architecture which faithfully mirrors the ambiguities, complexities and struggles of the contemporary urban experience, to be replaced with a singularly white, European image of human progress.

This calls to mind Walter Benjamin’s concluding remarks in his well-trodden essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, in which he describes the essential strength of fascism. The political ideology was so successful, he argues, precisely because it gave visibility to the masses and their desire for spectacle, without answering proletarian demands for a fundamental shift in property relations. Fascism protected the social order by turning its politics into theatre and divorcing the arts from its social context in the process. To combat fascism’s tendency to aestheticise politics, Benjamin suggests the very opposite, to politicise aesthetics, a conclusion that is as apt now as it was back then. Only with a political critique of architecture, examined as a product of its time and judged by its success in delivering on social justice, can we counterbalance the racist aesthetics of the right.