Insurrection. Rebellion. Revolution. Uprising. Riot.

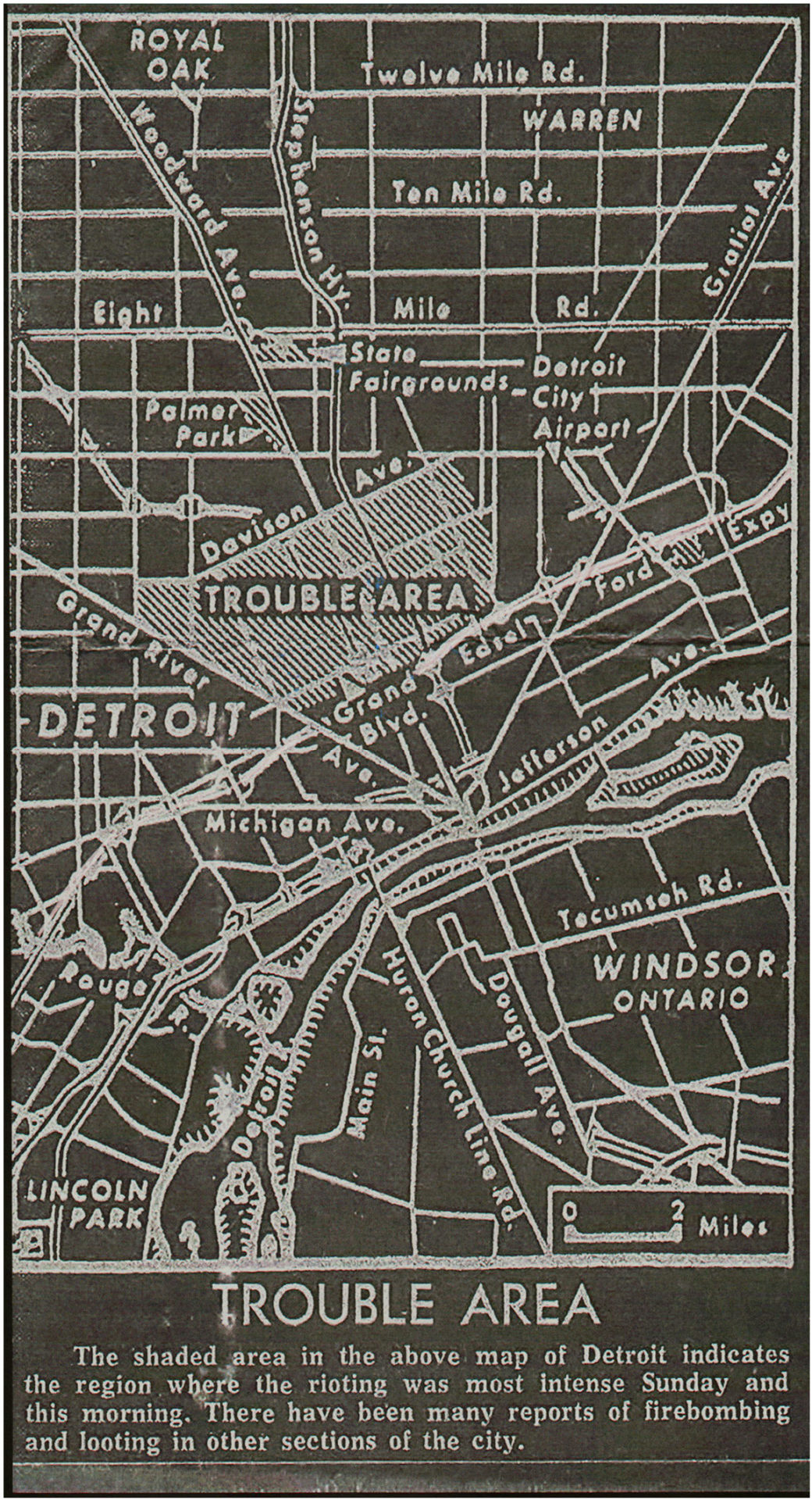

In the Detroit Historical Society’s Detroit 67: Perspectives exhibit, these terms were provided as possible answers to the question: “What word do you use to describe the events of July 1967?” Yet one word alone cannot define, enclose or master the force unleashed in the early hours of Sunday 23rd July, when police raided an unlicensed after-hours bar at the corner of Clairmont and 12th, where a crowd was celebrating the return of two local Vietnam War veterans. Although raids on “blind pigs” (as they were called) were a regular occurrence, the unusual distress of the crowd alerted neighbours who began to surround the police wagon and challenge their attempts at making arrests. As officers continued to apprehend people, and more bystanders joined the turmoil, aggression between police and protestors escalated, and tension began to spread throughout the city.

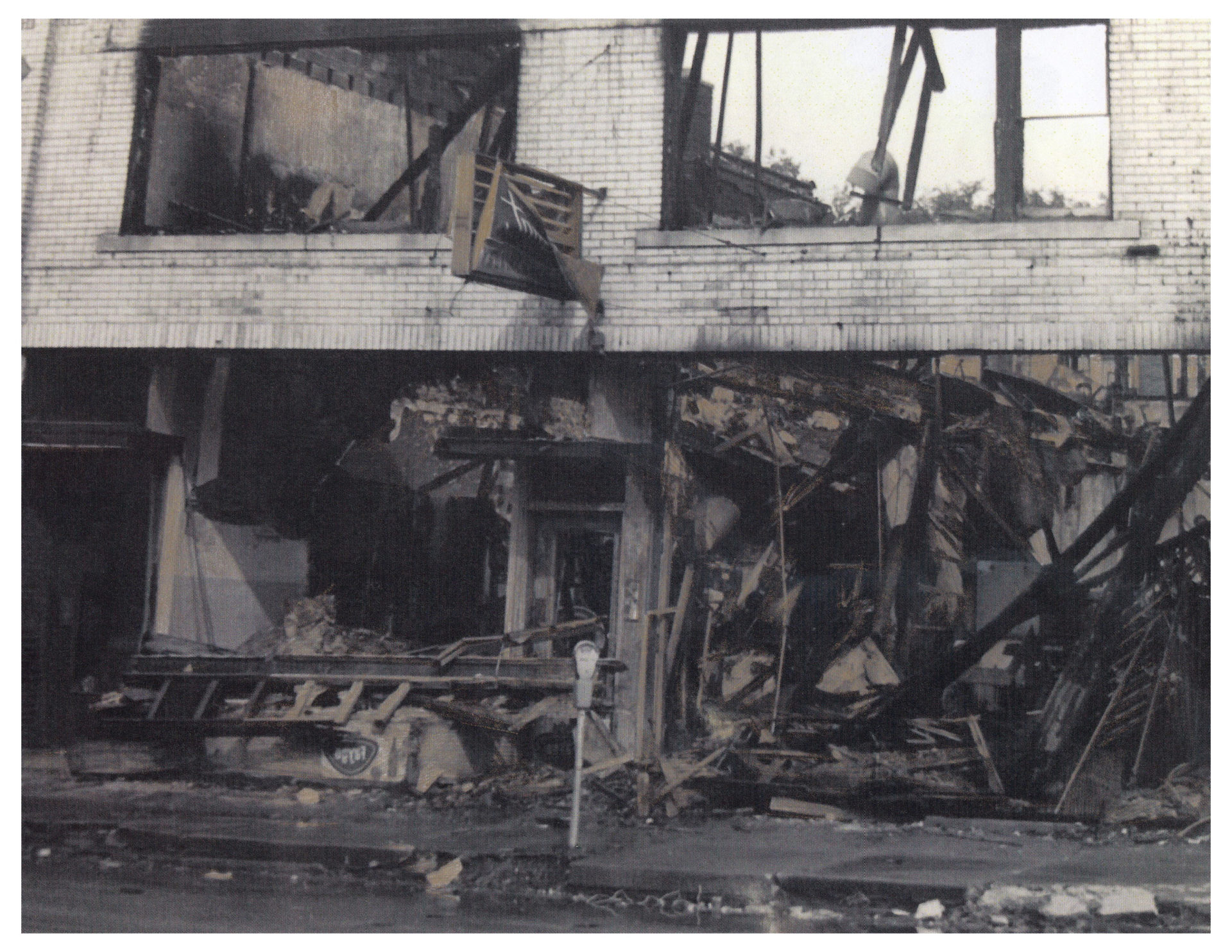

The Detroit Police Department (DPD) would unsuccessfully try to repress what soon became labelled a “riot.” By Monday morning, Michigan State Police were called in as the disturbance continued to grow. By midnight, President Lyndon Johnson declared a state of “insurrection”, authorizing the use of the National Guard. With the arrival of planes, tanks, and nearly 17,000 law enforcement units, this “insurrection” was put down; but only after five days of civil unrest resulting in 43 citizens killed, 1,189 injured, 7,200 arrested, and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed.

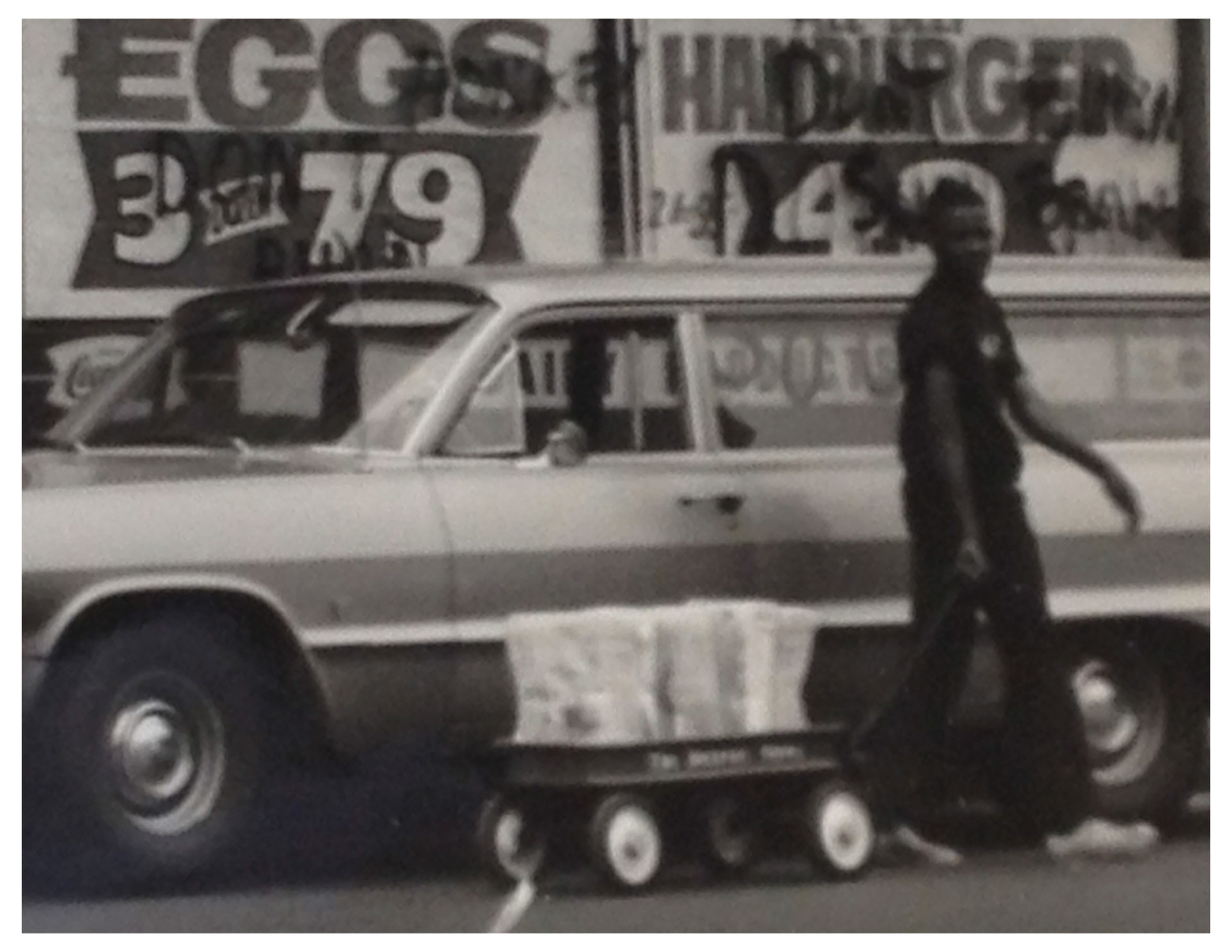

The unrest exploded into adjoining “Rust Belt” suburbs and cities: Pontiac, Flint, Saginaw, Grand Rapids, Toledo, and Lima — areas affected by the same racial tensions and infrastructural disparities as Detroit. When asked after the fact about what ultimately instigated these widespread disturbances, black respondents identified police brutality (from a 93%-white police force), as well as poor and ghettoized housing conditions.

Fifty years later, one must ask: why has the Historical Society, an institution in charge of officially narrating the history of Detroit, not found its own name for this event? Why is it so difficult to place a word in this context? And why is it so important to find a name?

What happened during the summer of 1967 uprooted Detroit’s urban narrative – nearly a century old – of infrastructural progress and racial integration. This narrative had been imparted by hundreds of African Americans seeking refuge in the city on their escape route from slavery. Detroit, then nicknamed El Dorado, was the last stop on the Underground Railroad leading from the Confederate states to Canada. The narrative would later be endorsed by generations of laborers leaving agrarian jobs in the South to migrate North and work at the factories of Ford, Chrysler, and Dodge, fuelling the expansion of the automobile industry and the success of the so-called “Motor City.”

The events of ‘67 not only proved the limitations of this vision, but also showed that its undercurrent was a racially and economically divided society. In one violent instant, 1967 dispelled the dream of El Dorado and accelerated the city’s decline. After the event, the racial gap took a distinctly spatial turn: white people fled to the suburbs, while black and impoverished populations remained in the increasingly abandoned “inner city.” At a time when global capital was shifting gears and the automobile industry was grinding to a rusty halt, the summer of 1967 was a tipping point in the spatial concentration of capital, the racialization of space, and the composition of Detroit’s urban fabric.

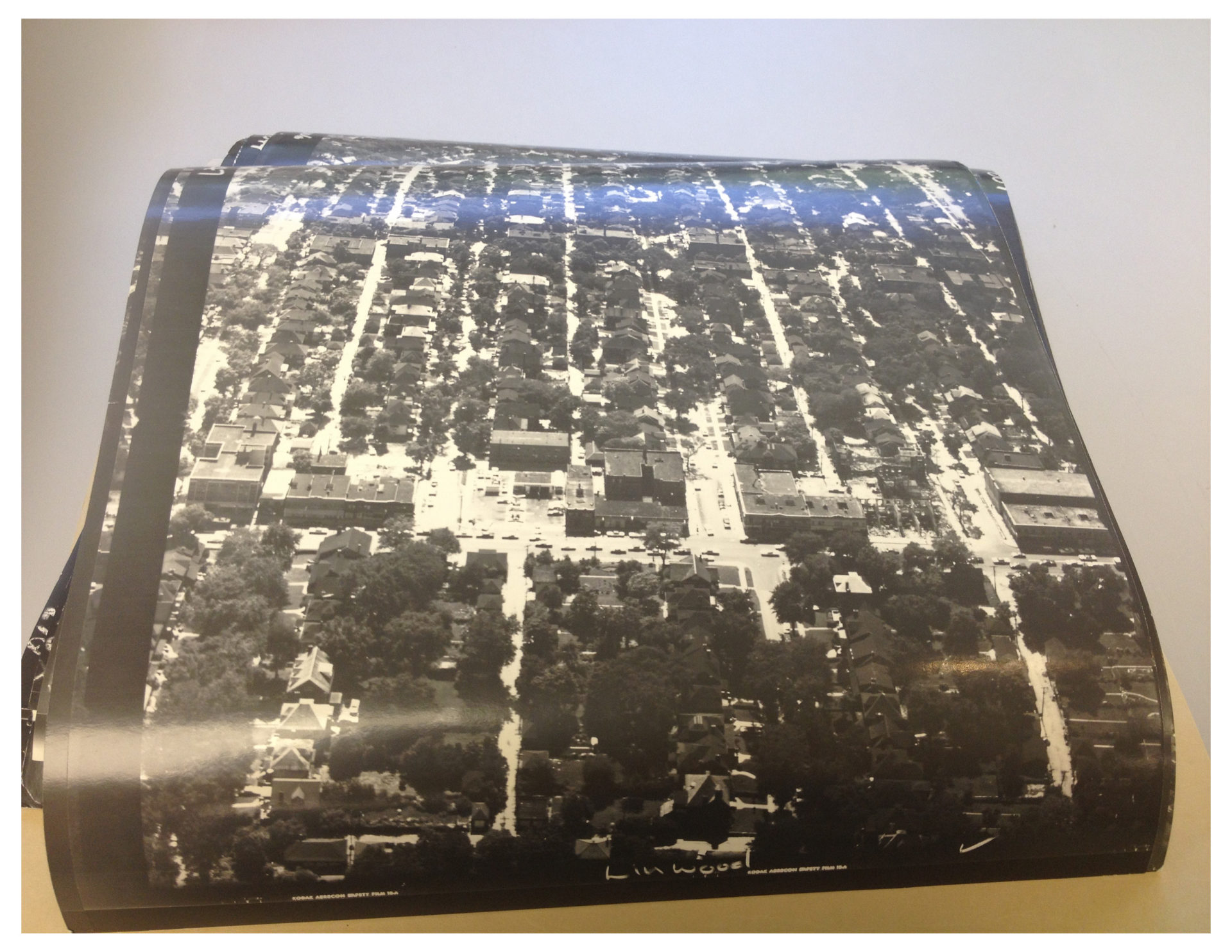

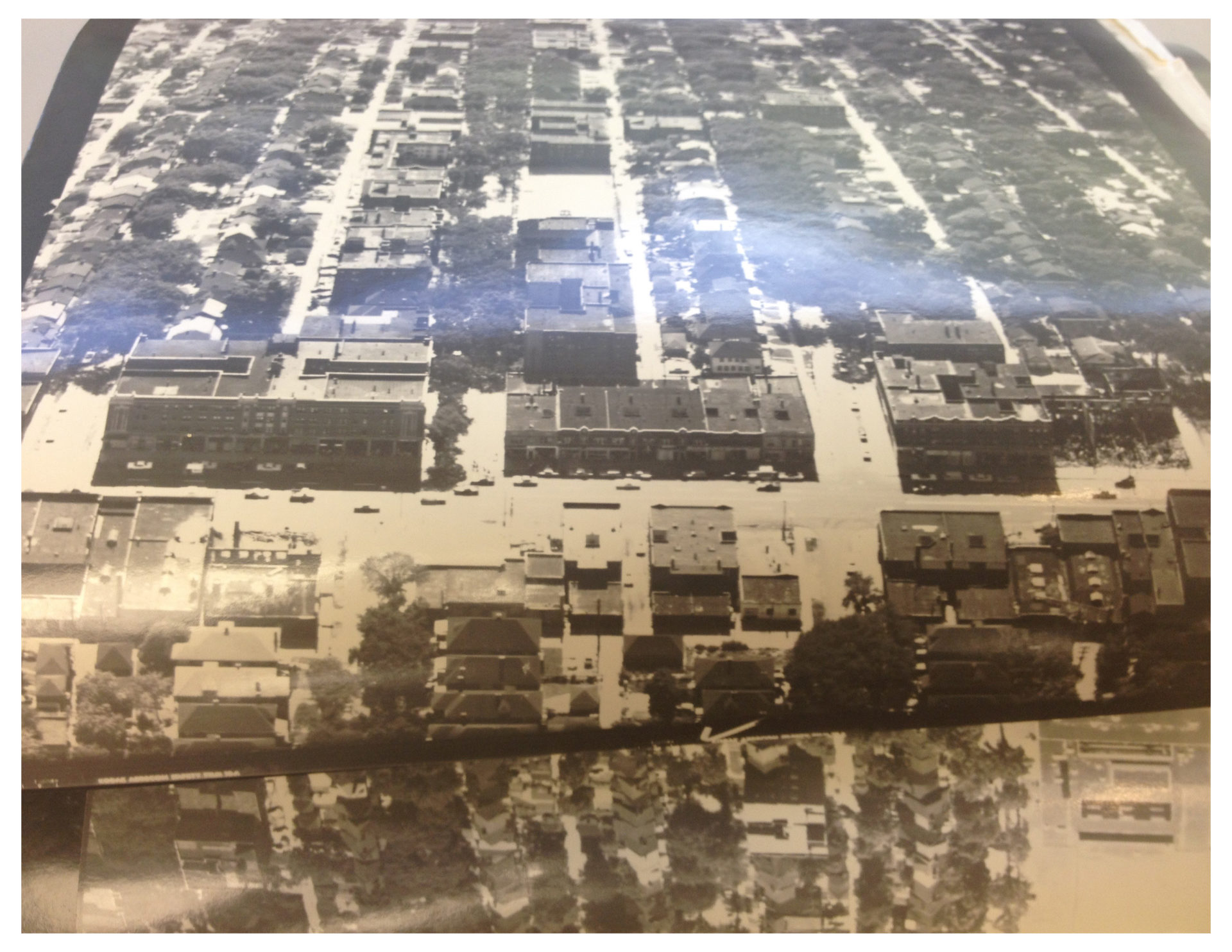

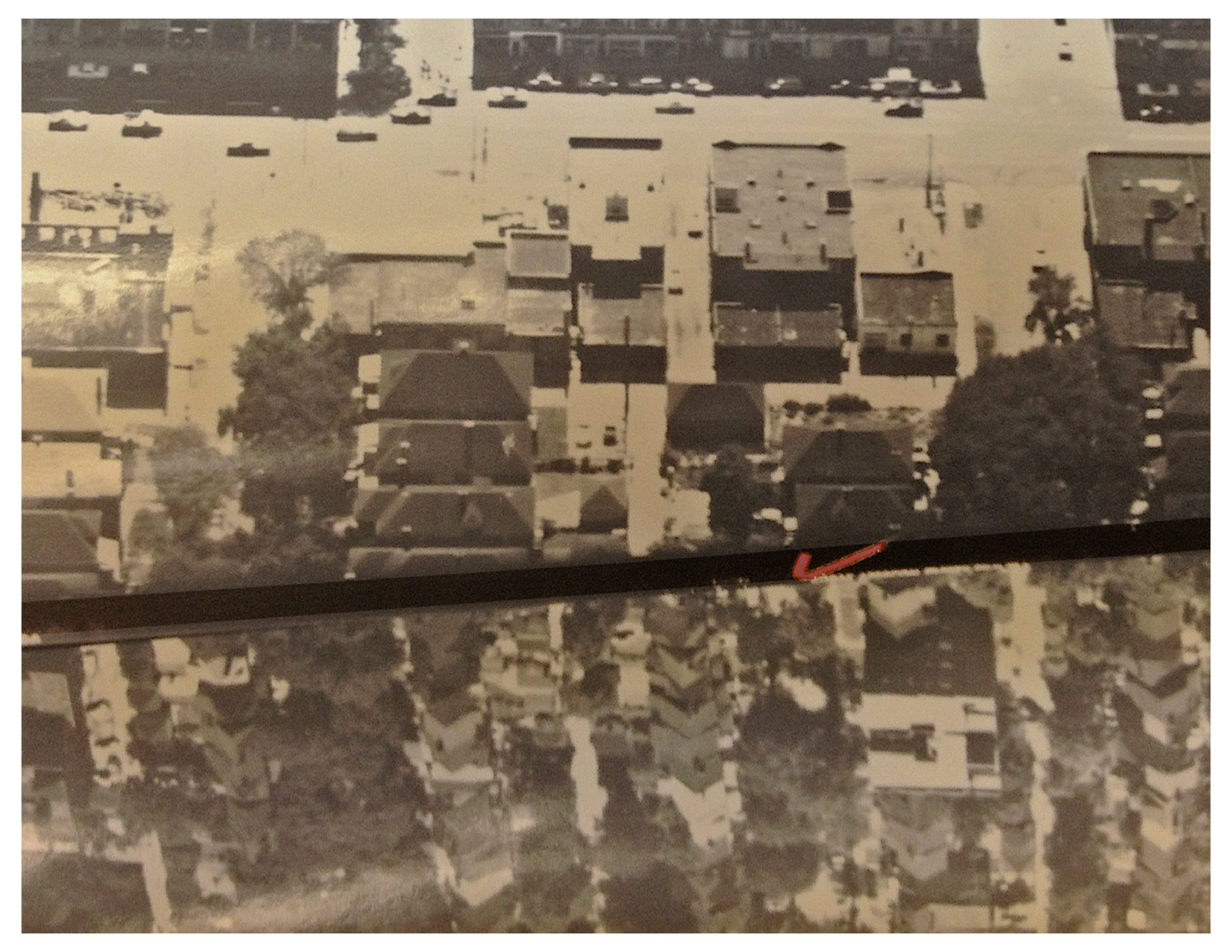

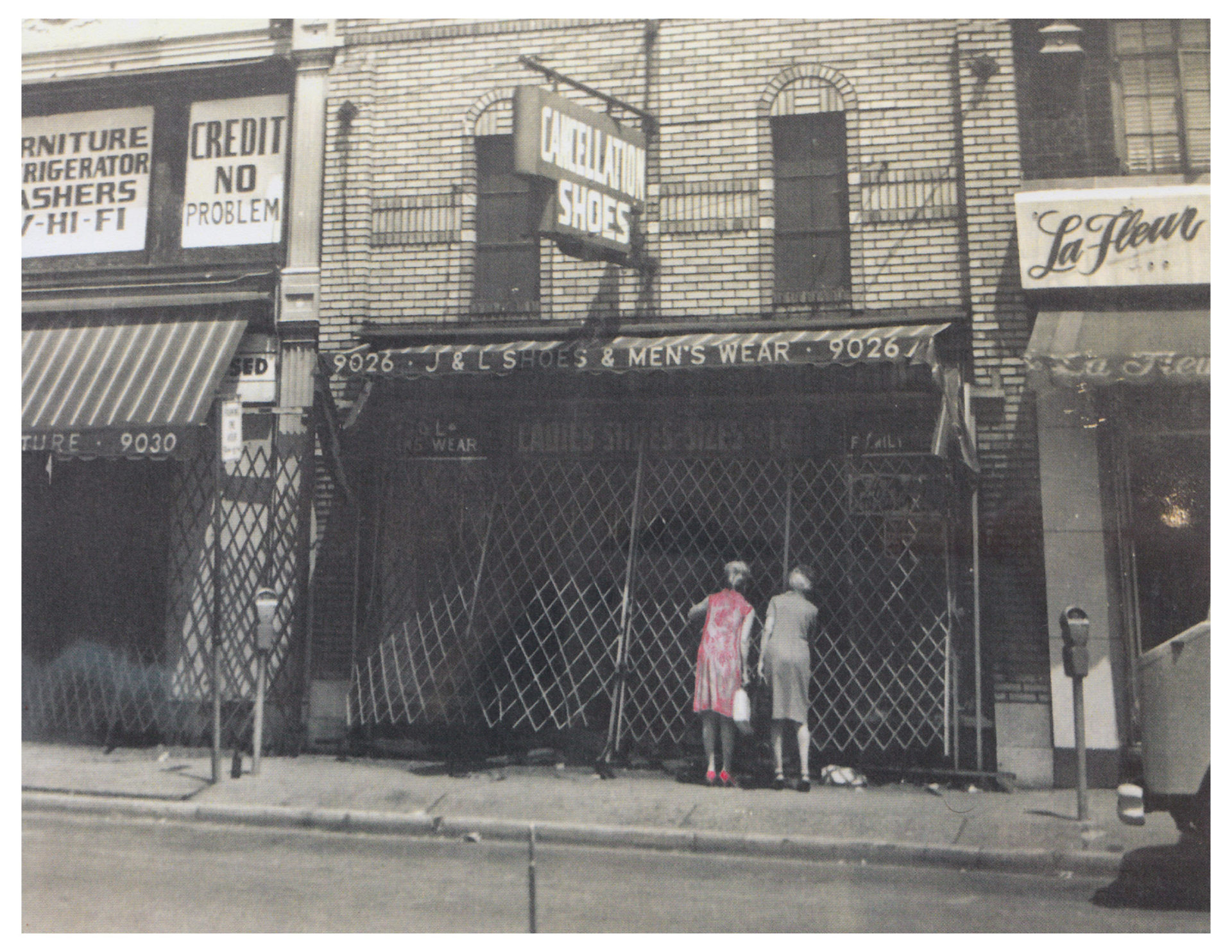

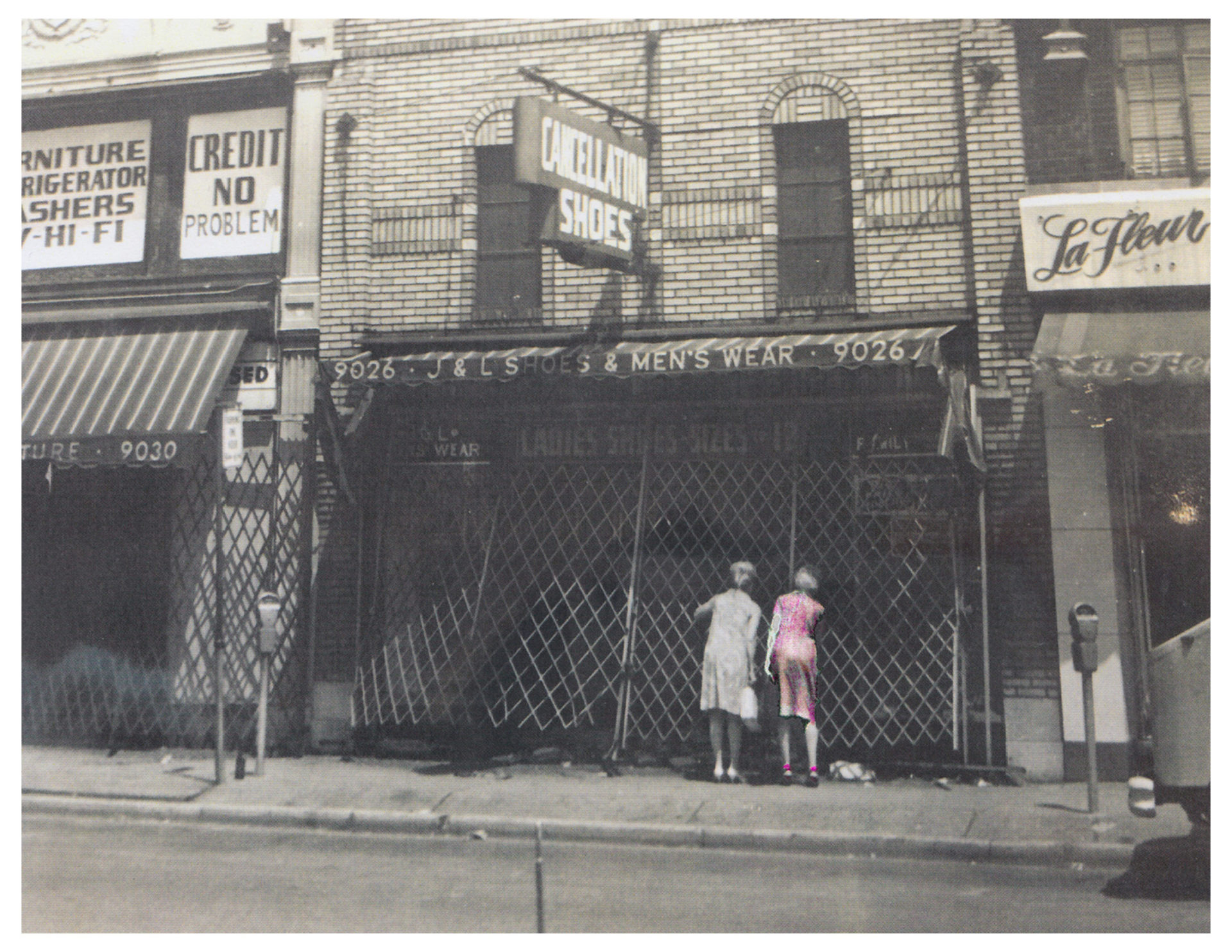

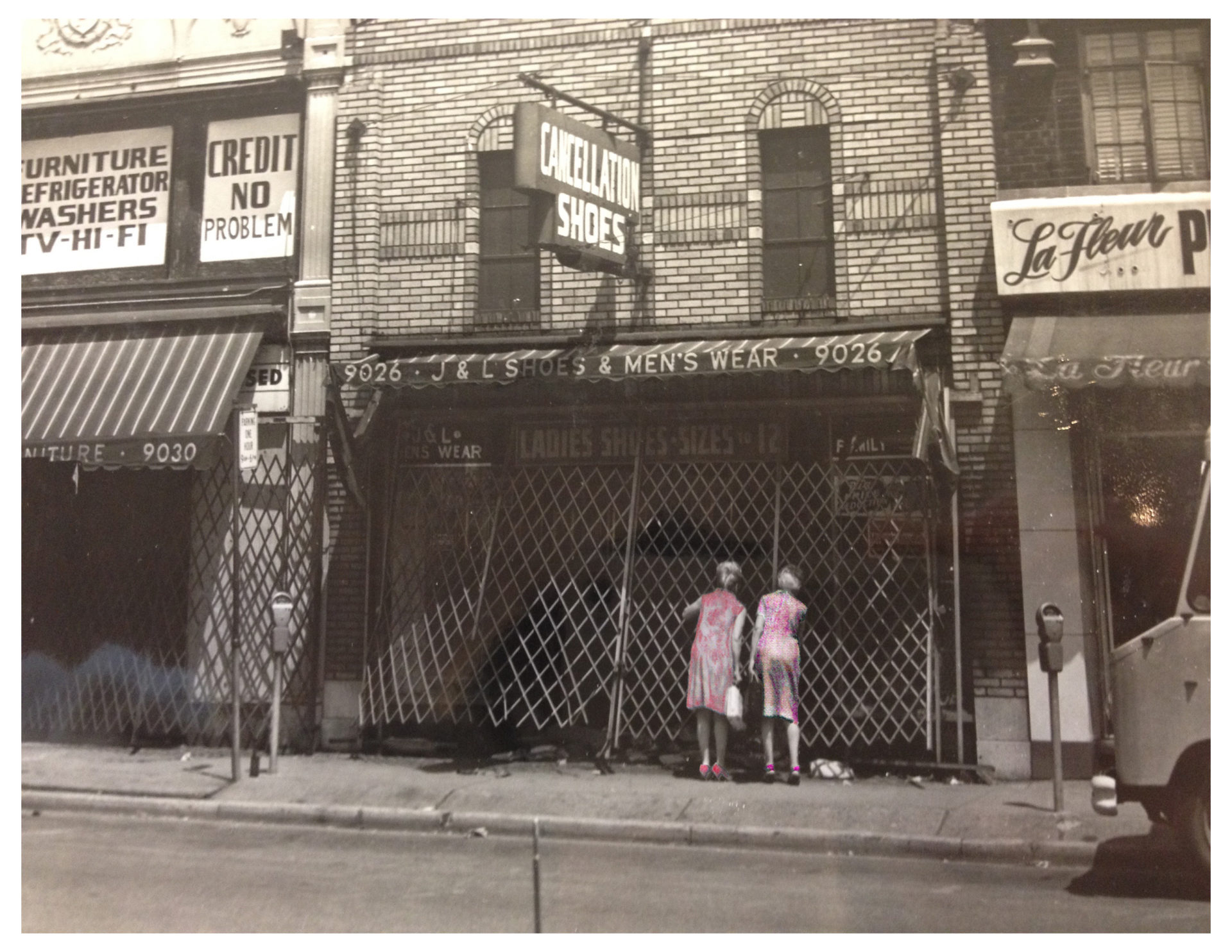

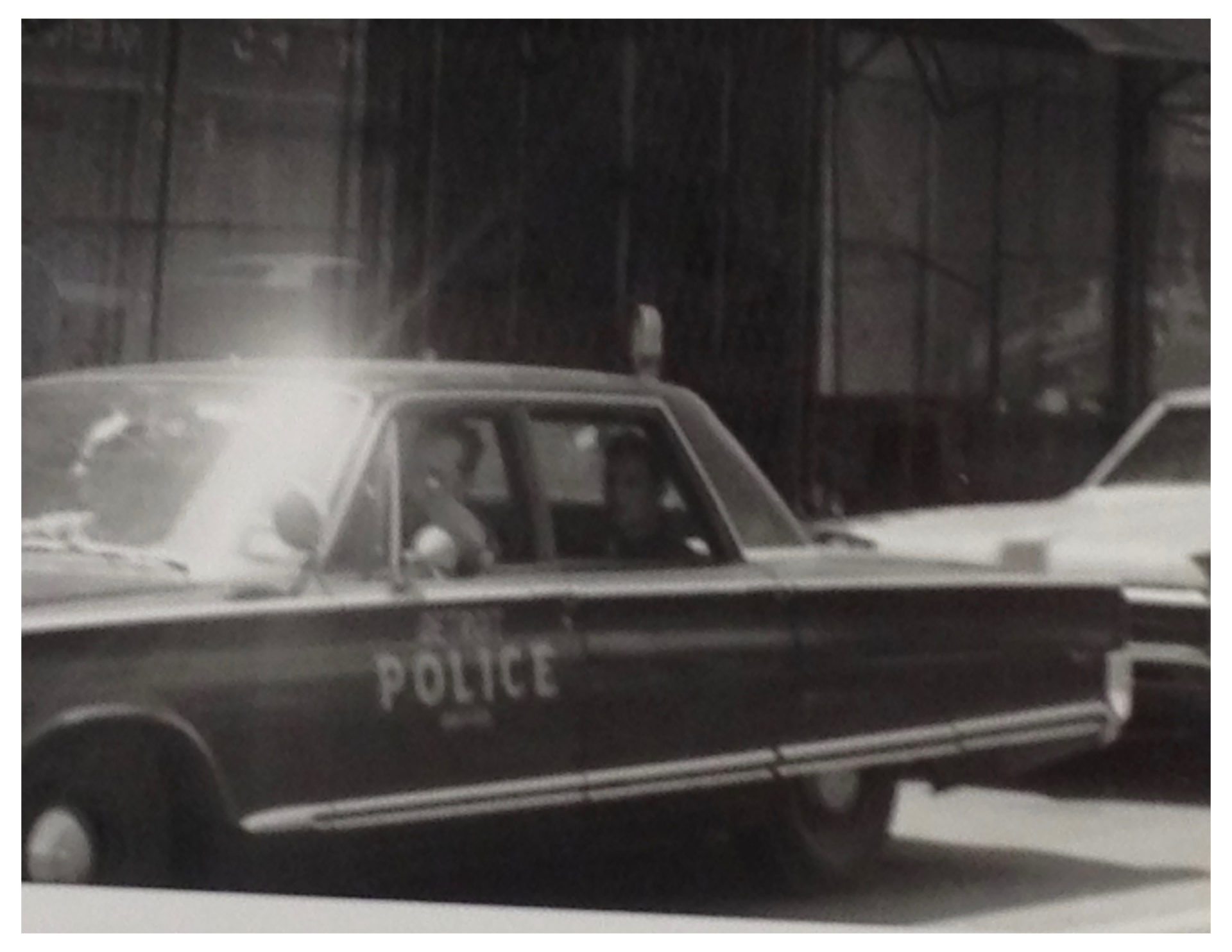

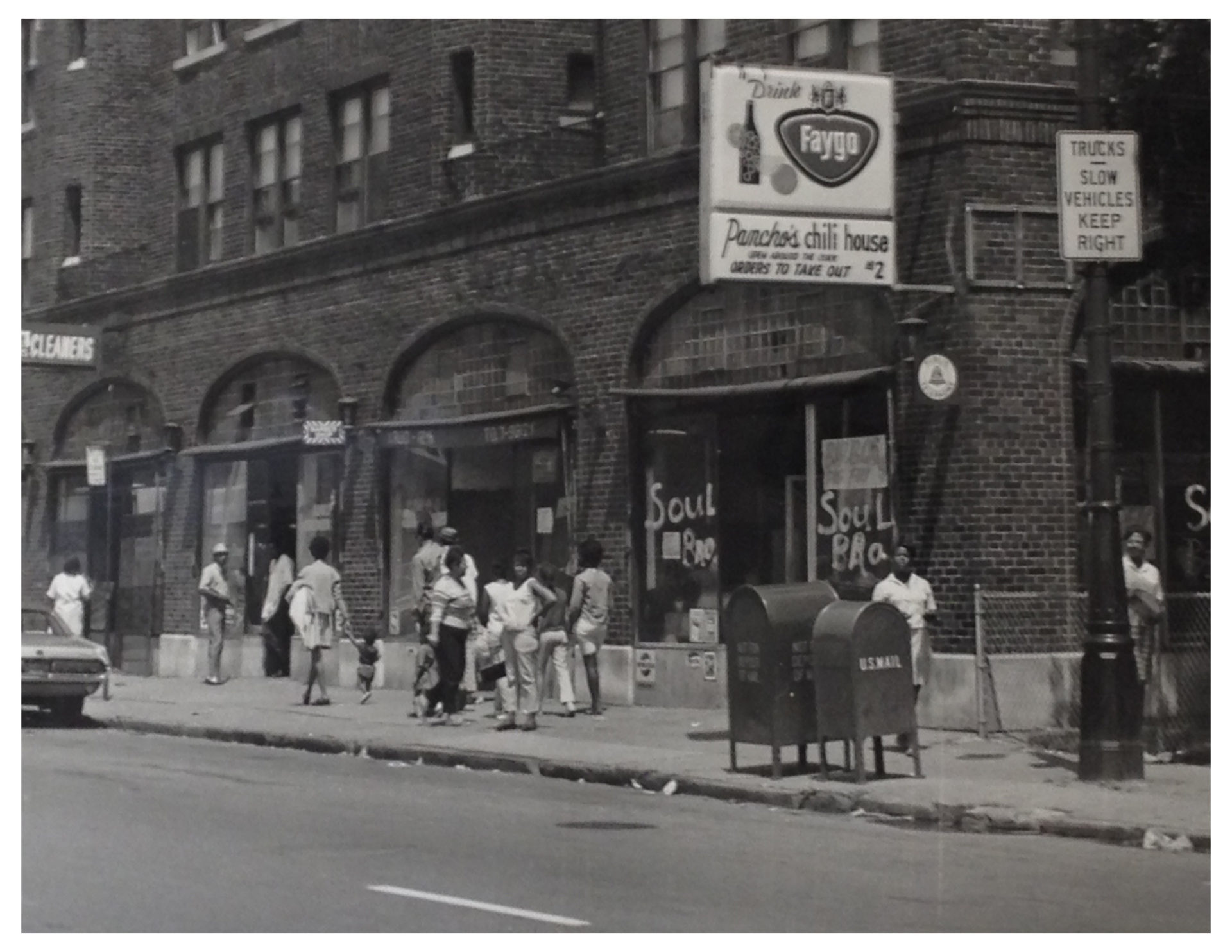

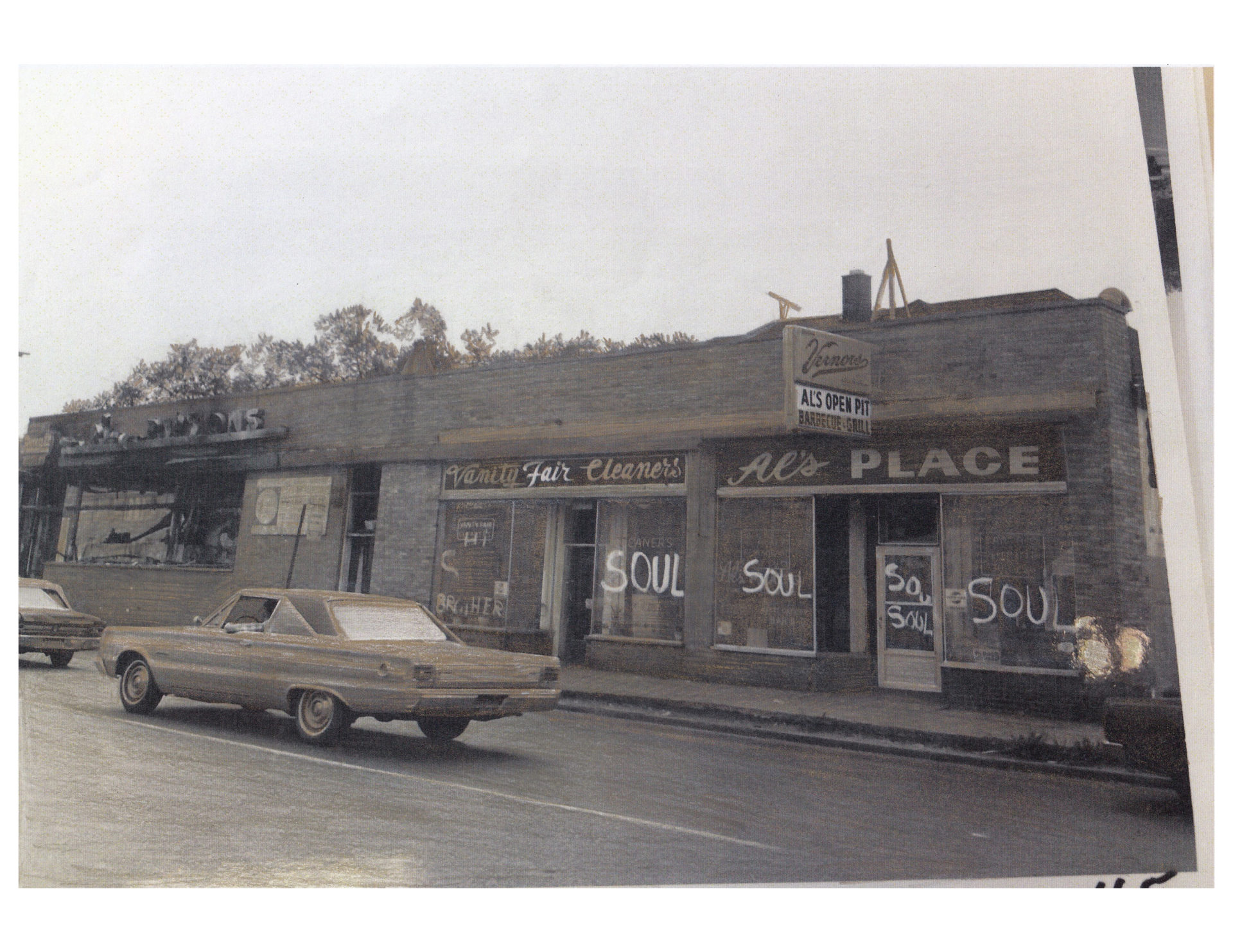

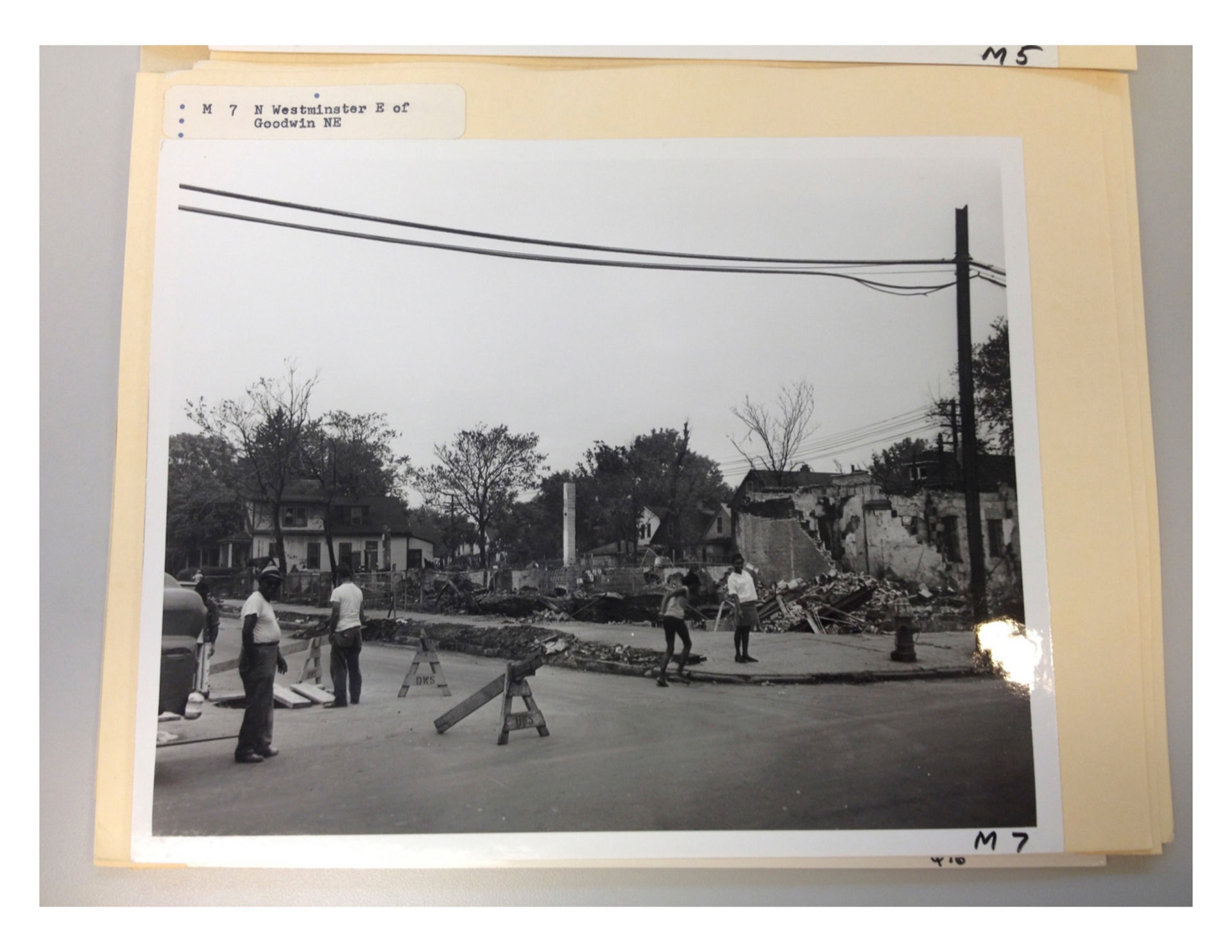

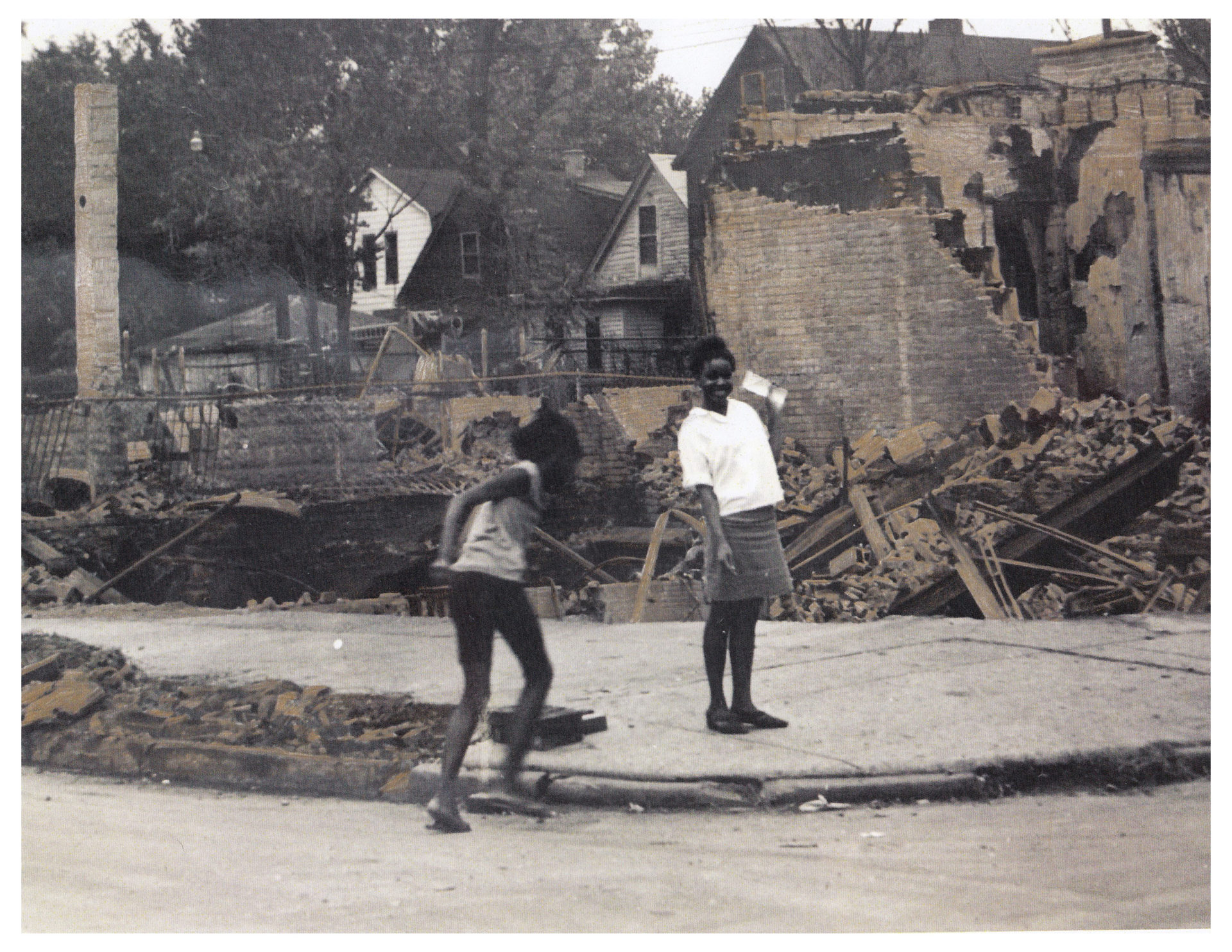

The museum’s inability to choose a name is an invitation to challenge its sole authority in narrating this history, and to turn our gaze and alert our ears towards other voices, other words and other inscriptions. The Police Photographic Archive (housed within the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan) offers that possibility — its photos a particular framing of the streets in the aftermath. Unlike the museum’s perspective, the vigilant gaze of the patrol car is not interested in historical neutrality; it does not aim to safeguard a narrative, nor to present a conciliatory image of the event. Conversely, the surveilling eyes of the police, trained to identify disruption or “damages to the infrastructure” (as the title of the archive declares), locate the emergence and traces of threats to state security, physical and symbolic.

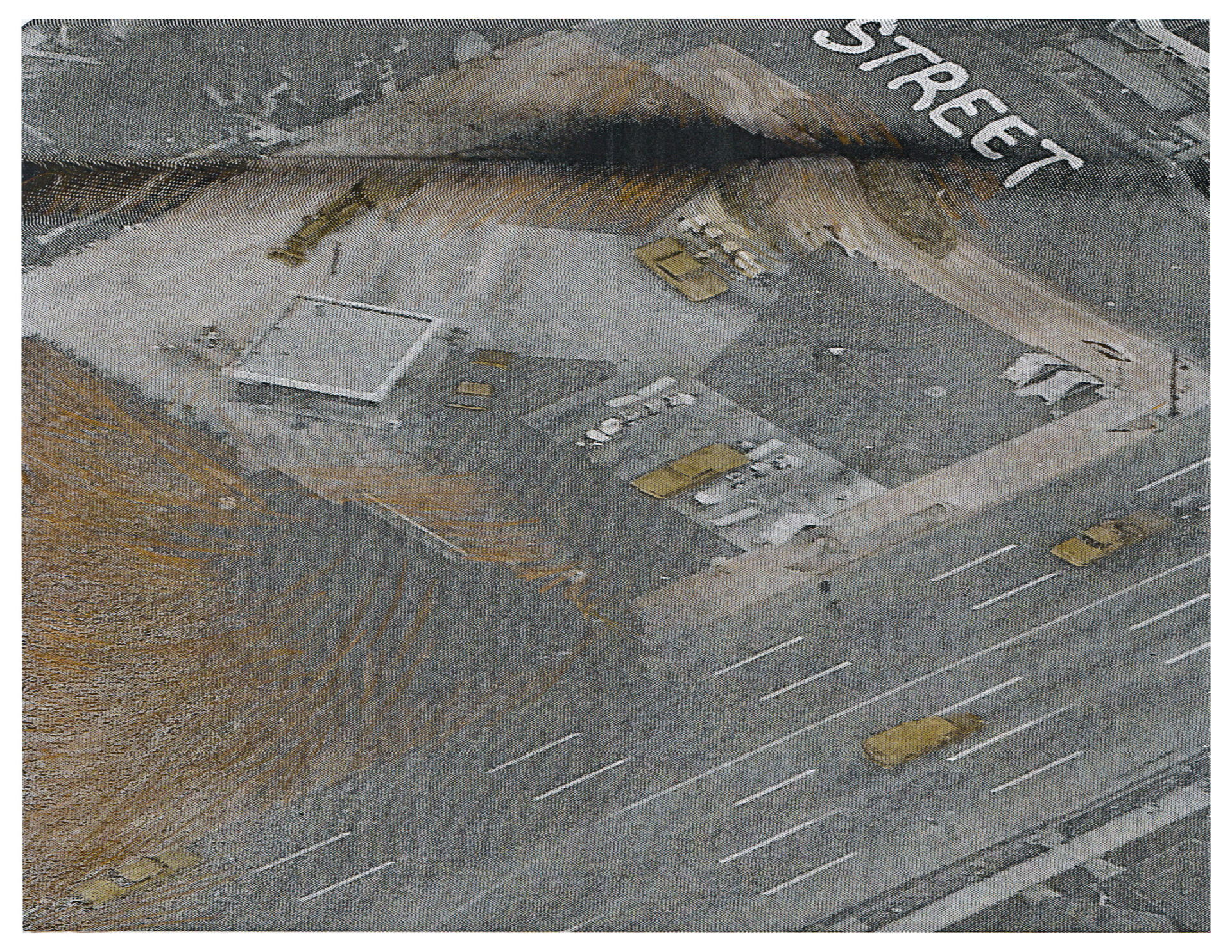

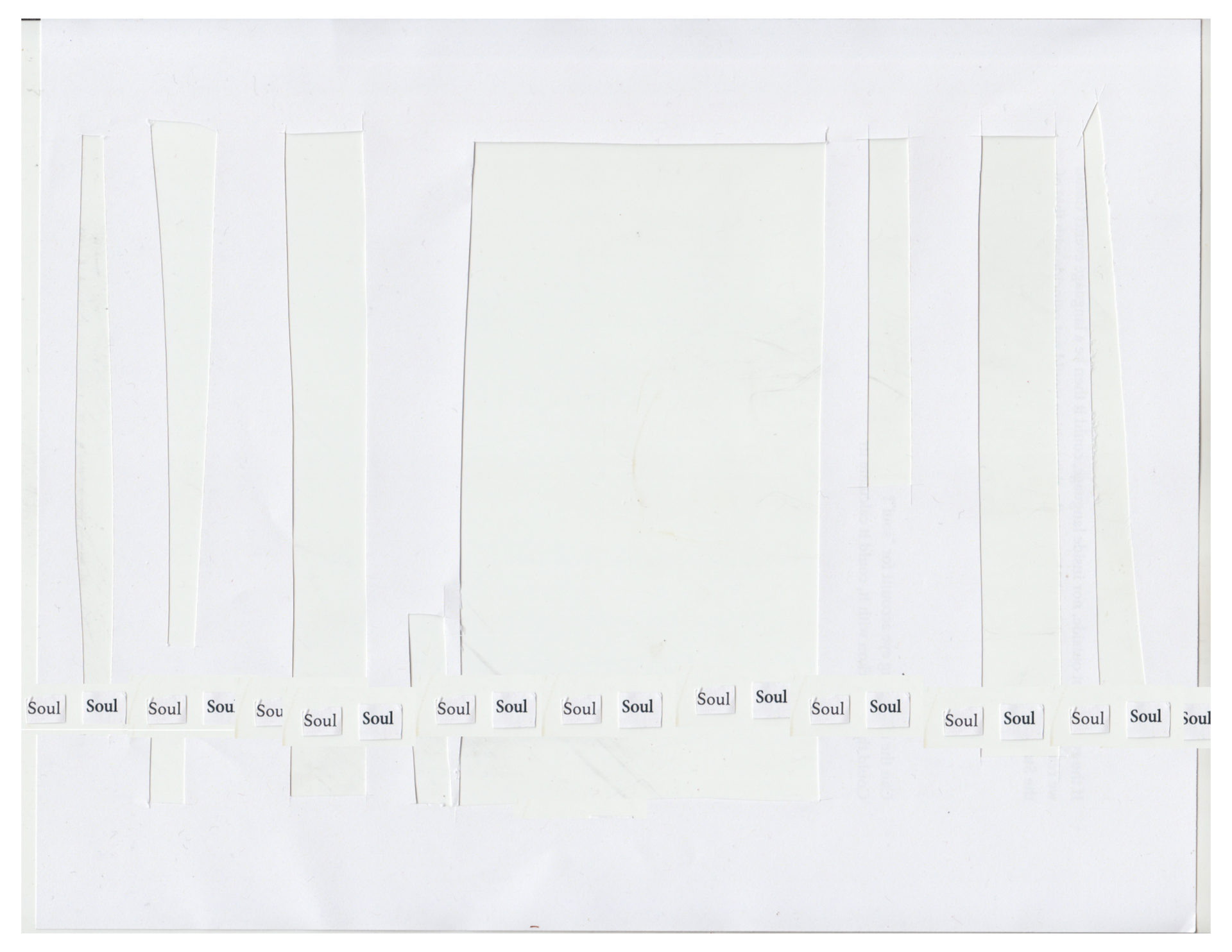

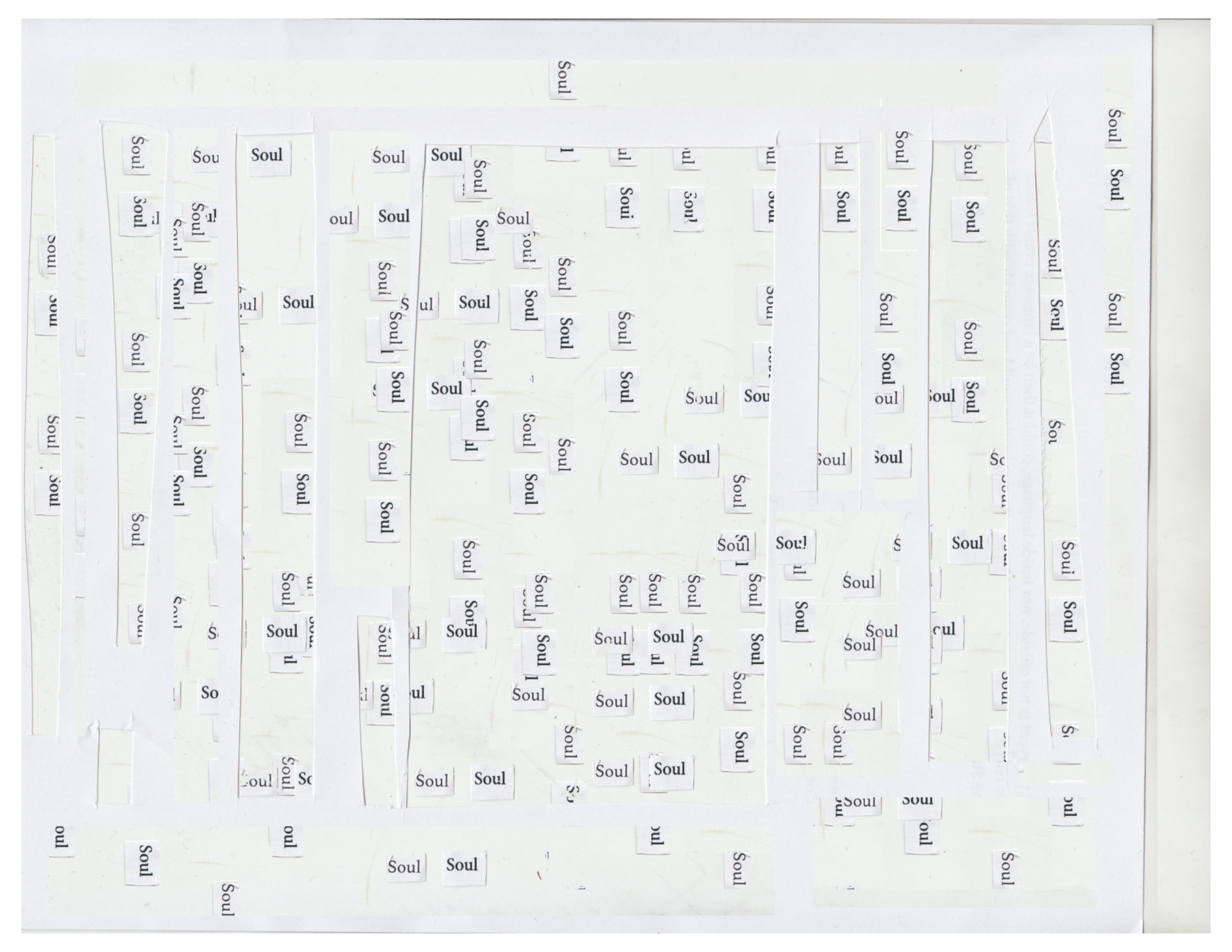

The images presented here are reading interventions into the visual archives of the Detroit Police Department (DPD), the National Guard (ANG) and the Detroit Free Press. Loosely divided into five sections, this visual essay questions how race, infrastructure, property value and police surveillance are articulated in the archive. In its final section, the piece reveals the traces of “soul”, a code or protective password used by black business owners to signal solidarity with protestors in order to preserve the integrity of their buildings. During their silent surveillance, the police managed to photograph the word “soul” written on glass storefront windows across Detroit. Registered, reiterated and distributed by the police itself through their surveillance operations, “soul” enters inconspicuously into the institutional archive. These reiterations of “soul” function as landmarks of a different territory, independent from the “protective” powers of the police. “Soul” as the path of a different sort of power.

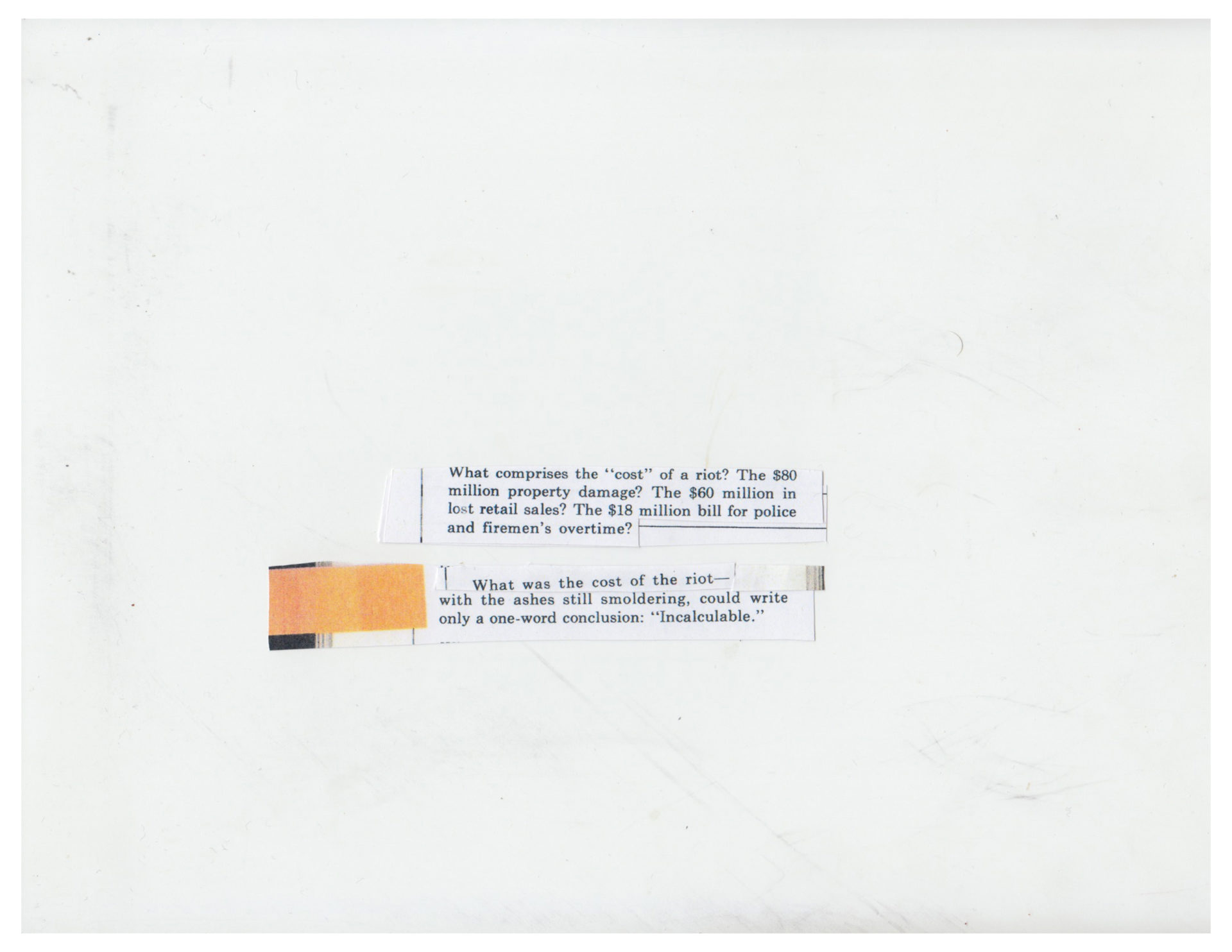

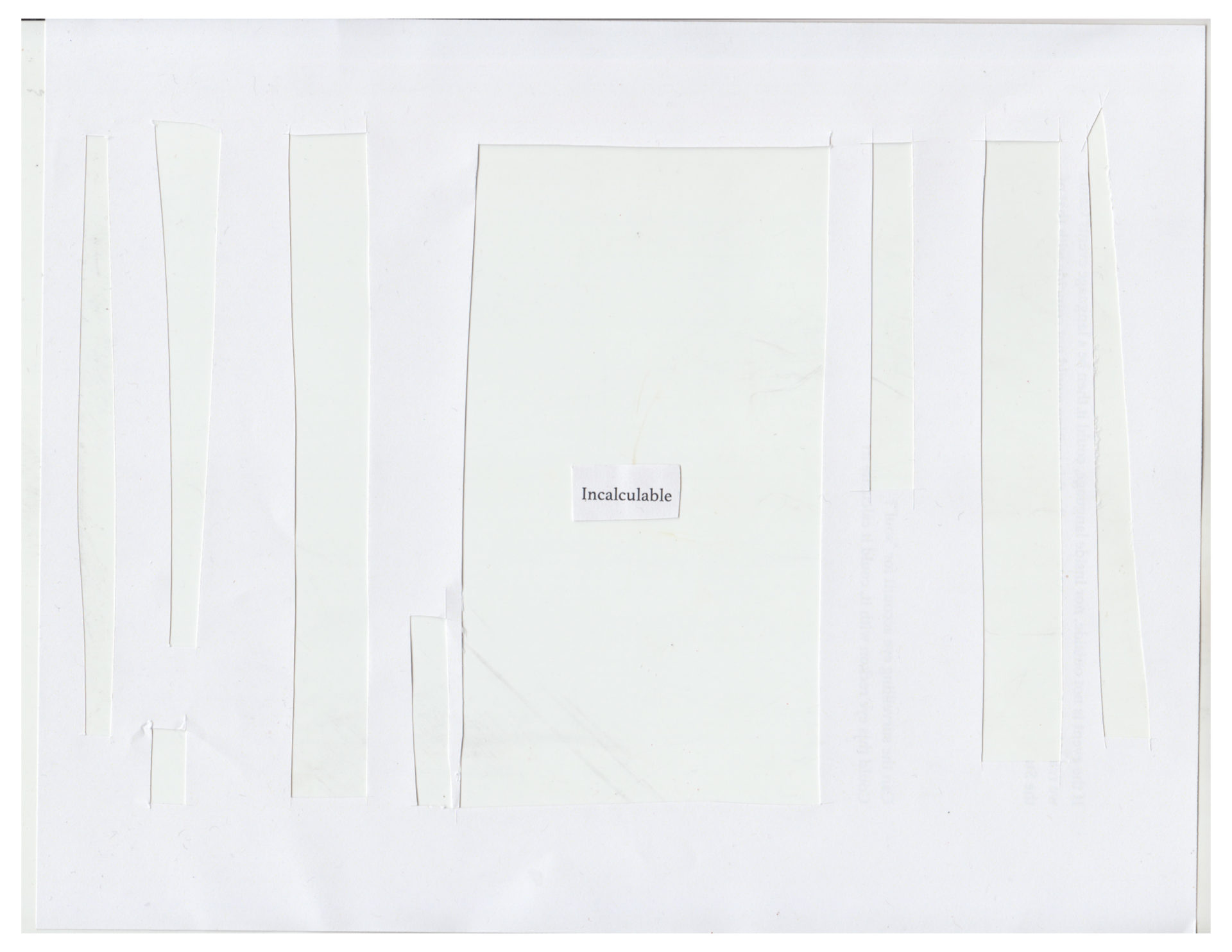

Going through the archive, the viewer starts to wonder: in this particular case, what exactly constitutes infrastructural damage? Was unequal accessibility and quality of infrastructure not one of the main triggers of the uprising? Did black populations not endure oppressive and discriminatory infrastructural conditions? Was failing infrastructure not already a wound? In Detroit, the historical inquiry of justice must necessarily deal with questions of race, value and infrastructure, for racial surveillance is the close companion of racial violence — a dual aggression that has survived the events of ’67. If race, infrastructure, and property value determined the conditions of the political then as they do now, fifty years later, we should ask: what does it mean to commemorate these events?