It’s the season of sentient streets, augmented homes and “smart” cities, and what better way to visualize it than with images from Sidewalk Labs’ pitch for a “smart” Toronto waterfront. The images are timely but they add more than mere eye candy to the social flow of news. Taken as a whole, as a collection of sorts, they also show how private power and public relations course through journalism.

Images swim faster than words. They reverberate in print and proliferate wildly on the Internet, rallying a certain kind of public around a particular plan, project, event or episode. This is what Mark Minkjan describes when architectural renderings seduce a certain kind of stakeholder. It’s also what Maryam Gharavi describes in Metahaven’s The Sprawl (Propaganda About Propaganda), when a cinematic political clip “enacts or performs its audience”.

Images also haunt the public memory. In a time of optical overexposure, “the problem is not that people remember through photographs,” writes Susan Sontag, “but that they remember only the photographs . . . To remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture.”

Images are direct and memorable, making them key tools in the power brokering of architecture, real estate and geopolitics. However, this insight may be more a matter of basic visual literacy than a particular genius for journalism, global affairs and propaganda (or its rebranding as “public relations”). Yet for two years, without critical reflection, countless journalists, art directors and editors download Sidewalk images and use them for their stories. No questions asked.

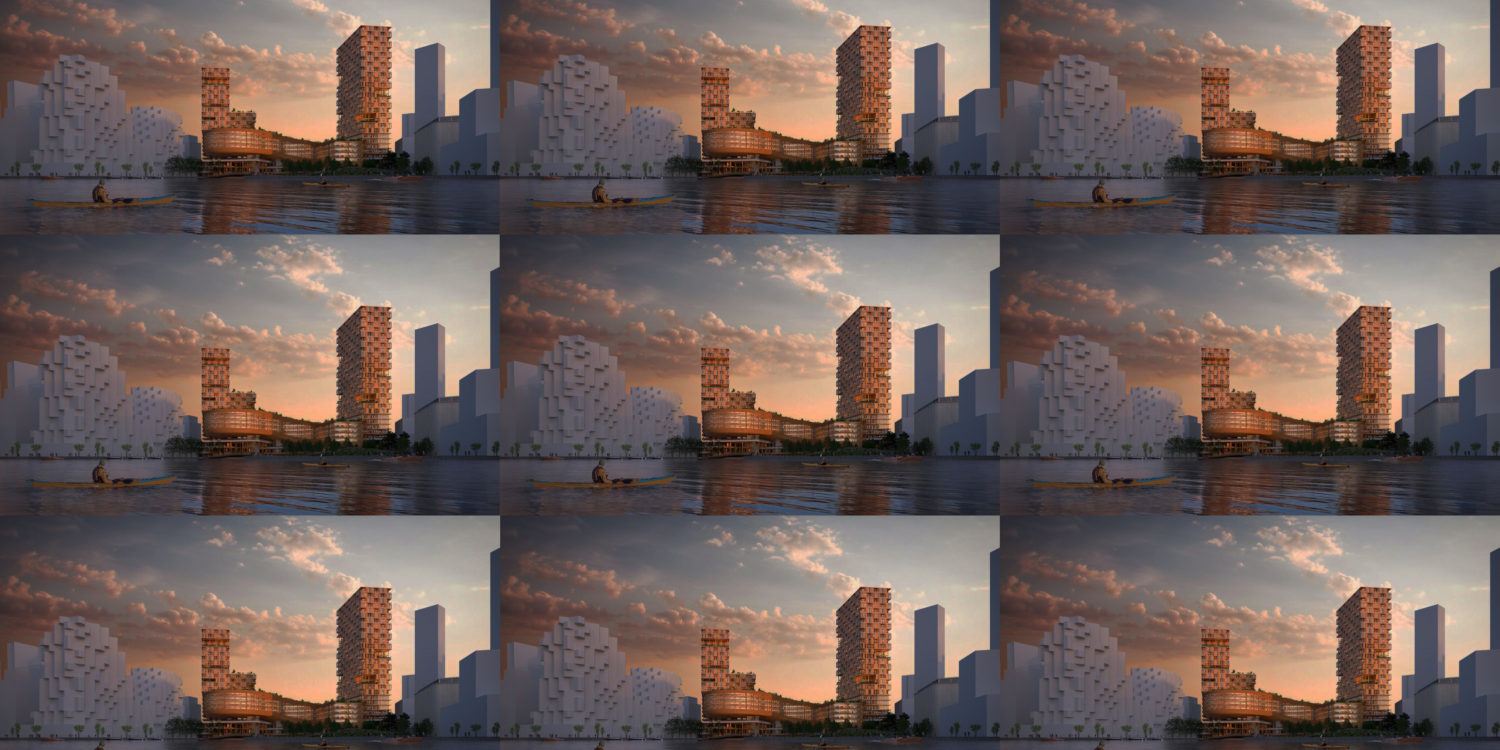

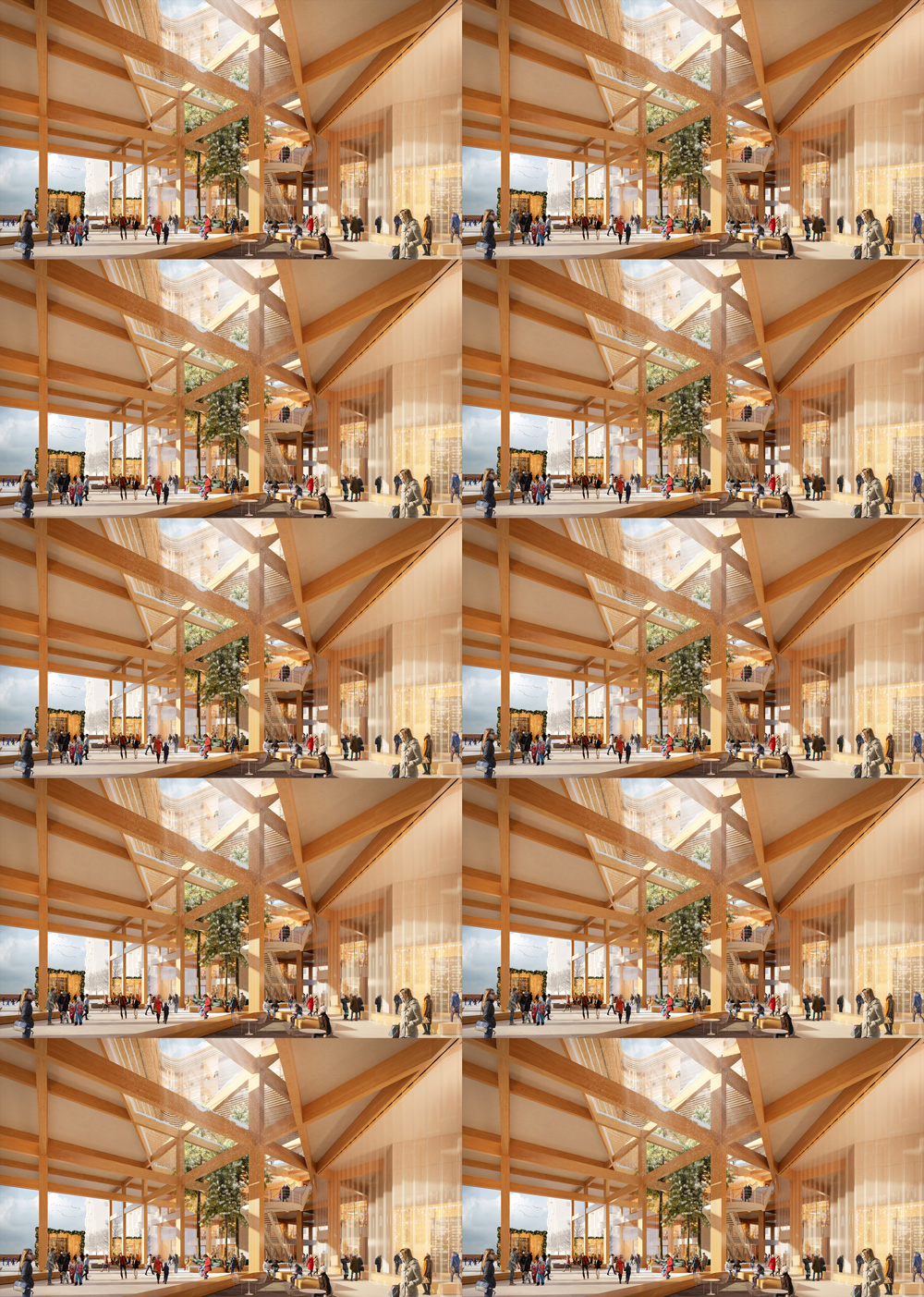

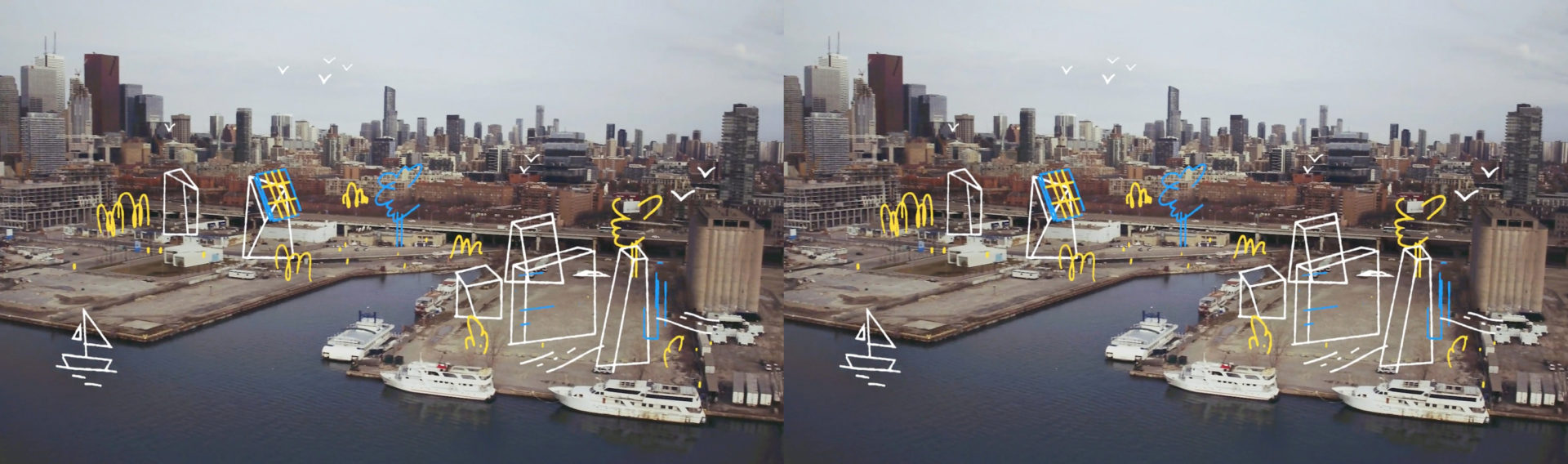

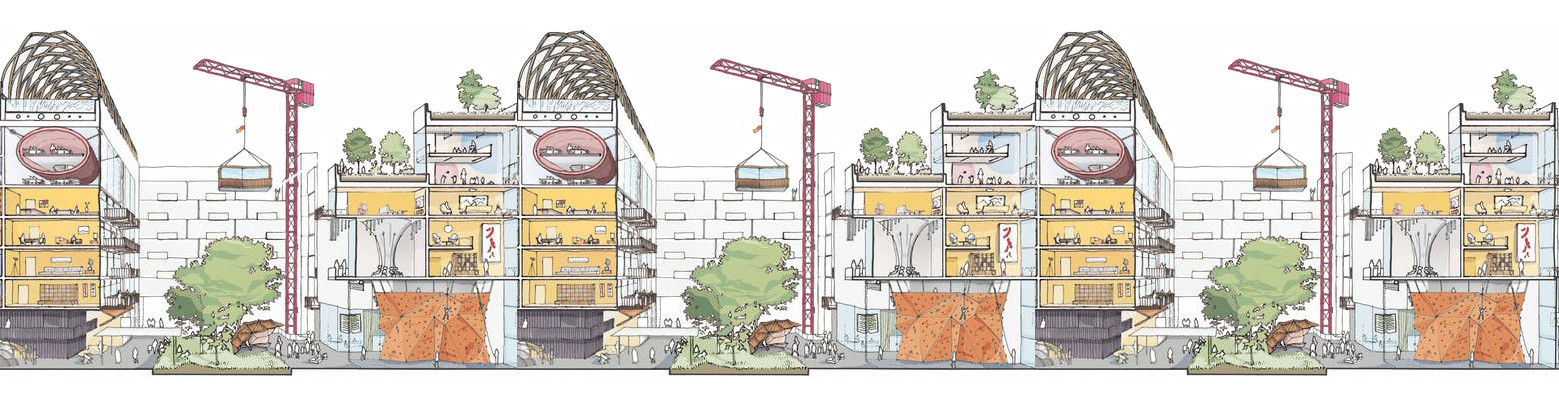

Sidewalk Labs is the New York-based “urban innovation” company launched by Google prior to its transformation into Alphabet Inc., the multinational tech giant based in Mountain View, California. To promote its ambition to build a “smart” neighbourhood on Toronto’s waterfront, Sidewalk has commissioned renderings, illustrations and doodles from Rick Berkelmans, Beyer Blinder Belle, Andrew Edwards, Cécile Gariépy, Ben Hughes, Michael Green Architects, Julie Muckensturm, Jason Polan, Snøhetta, Emily Taylor, and Picture Plane for Heatherwick Studio (a design practice that breeds blunders for Boris Johnson in London, England). As part of their visual portfolio, Sidewalk even include a series of documentary photographs from The Canadian Press, a leading Canadian news agency in Toronto, Ontario.

A commission. A selection. A suite of contributors. A body of work. The collection gathers players and pieces to help pitch Sidewalk’s private power. Enabled by an enthusiastic press in Canada and elsewhere, the Sidewalk collection first sprinkles, then floods the media landscape.

This raises an interesting question: Why are journalists so eager to publish Sidewalk’s public relations? Going back in time to the launch of Sidewalk Toronto provides a clue.

The Sidewalk collection begins rolling out on 17 October 2017 with the public announcement of Sidewalk Toronto. With one logo and one website, Sidewalk Toronto is billed as a “joint effort” between Sidewalk Labs and Waterfront Toronto, the un-elected, moderately effective tri-government corporation tasked with developing Toronto’s eastern waterfront. A joint effort. A dream team. Working on the project together. Collaboration becomes the name of the media frame.

But this is only half true. Legally, Sidewalk Toronto is a limited liability partnership, in which Waterfront Toronto has no apparent legal standing. The partnership names Sidewalk WT Master Developer GP, Ltd. as the general decision-making partner. As Mariana Valverde and Alexandra Flynn discover, the partner has the same street address as Google itself.

Sidewalk Toronto’s governance is complex but the public launch is straightforward, high-powered and positive. Sidewalk Labs’ chief executive, Dan Doctoroff, is there — the investment banker with a hand in the “hot mess” that is Hudson Yards in New York City. Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau and former Alphabet chairman Eric Schmidt also attend. They take turns straddling the lectern with beaming smiles. A large part of Trudeau’s charm lies in his youthful “sunny ways“, and Schmidt follows suit with his brand of “radical optimism“. Sunny. Confident. Cheerful. It’s the ideology of positive psychology elevated to the level of public-private statecraft.

“Eric and I have been talking about collaborating on this for a few years,” says Trudeau. “And seeing it all come together today is extraordinarily exciting.”

The rollout is well-funded. Sidewalk budgets $11 million USD for communications, engagement and public relations. This includes intense government lobbying, building influencer networks and commissioning artists, designers and architects to generate images that fit the Sidewalk script.

The image production is an instant media hit and starts flowing through BBC.com, Bloomberg.com, CBC.ca and CNN.com, as well as Azure, Canadian Architect, Haaretz, L’Actualité, La Presse, Le Figaro, Fast Company, Le Monde, Globe and Mail, National Post, New York Times, NRC Handelsblad, Radio-Canada, Spacing, Toronto Star, TVO and Wired. The scale and reach of free publicity given to Sidewalk is astounding.

Fast forward to the present, and the collection now leads almost every major news story on Sidewalk, whether it’s good or bad press. In March 2019, when the Canadian Civil Liberties Association threatens a lawsuit against Waterfront Toronto for unlawful public surveillance, the Sidewalk images are there. Golden towers lead the Globe and Mail report. Derelict waterfronts appear in CBC.ca and the Financial Post. Dreamy renderings lead Fast Company and the Toronto Star, and utopian illustrations lead BBC.com and MIT Technology Review.

The press credits Sidewalk’s images as “Sidewalk Labs” or “The Canadian Press/HO”. When a derelict waterfront leads a 680 News report, the caption reads: “Sidewalk Labs says it is keen on reviewing and perhaps even implementing recommendations made by a panel of millennials for the Alphabet Inc.-backed company’s proposed high-tech community in Toronto. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO, Sidewalk Labs *MANDATORY CREDIT*.”

Short for “handout”, HO marks a free promotional image given to the media by press agents working in government or business. This mark then hides in plain sight. For those within the media industry, the mark is visible, meaningful and gestures transparency. Whereas for those outside, it is seldom noticed and remains opaque.

The different styles of Sidewalk’s collection carry substance. The documentary photographs of Toronto’s “scrappy” eastern waterfront communicate candour and embody the legal doctrine of terra nullius (nobody’s land), when land is deemed unoccupied and therefore rife for colonization and development.

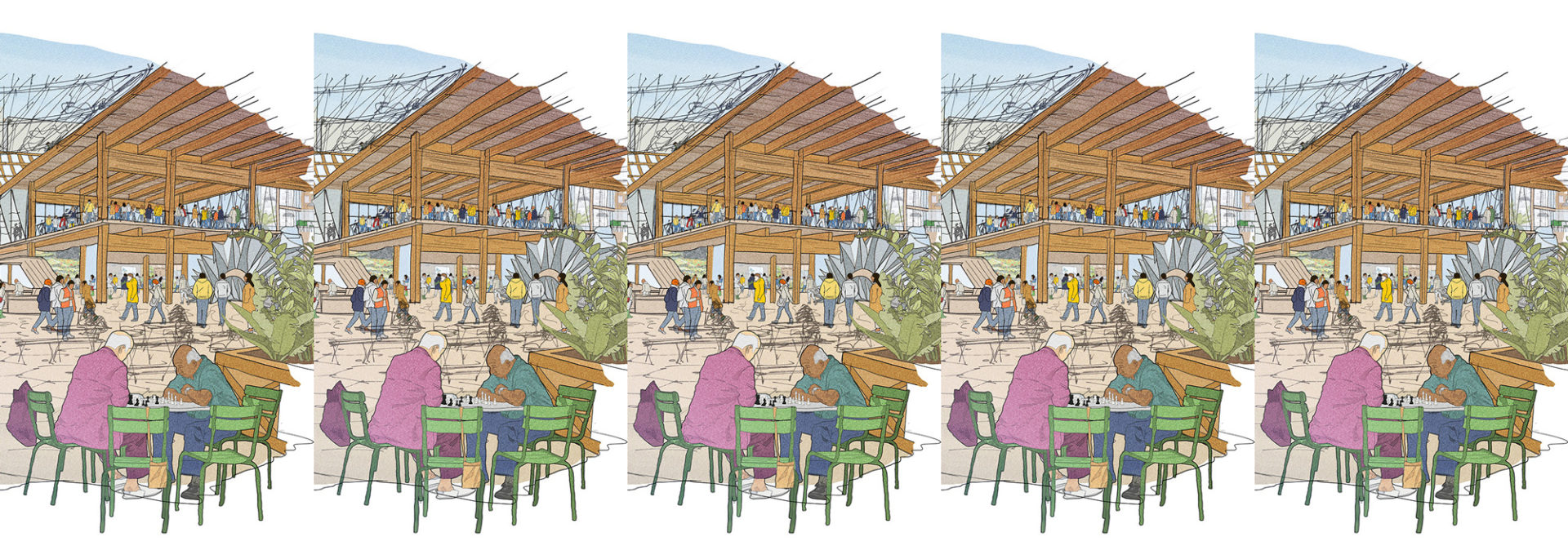

Other images speculate on future builds. Renderings are full of realism, waterscapes are laced with nature and romance, and illustrations have a lively community appeal. Such elements are newly possible with the loosening of old publicity codes within architecture, when men would tower over models in front of a camera.

Sidewalk may sell a grand Robert Mosian masterplan dreamt up by ministers and executives, but its visual narrative is more like a Jane Jacobsian street festival. The narrative portrays warm timber courtyards and detailed vistas with kayaks, kites, kids and seniors rendered in Everyday Bruegelian Fiction and Child-Like Utopian Watercolour. Meanwhile, the Silicon Valley vector style known as Corporate Memphis adorns Sidewalk Toronto’s Instagram account and 307 office.

The point is not narrative coherence necessarily. It is not to tell a linear Jacobsian story. The point is to blanket the media with visual diversity, giving journalists and readers a wide-ranging tour of the city of Neo Sidewalk, the privatized “City in a Box”.

The switch from Moses to Jacobs has not gone unnoticed, but the collection does more than camouflage a top-down masterplan. It produces its own soft power, promoting Alphabet’s economic order while scrambling democracy’s political order: baffling, bumping and undermining any meaningful public understanding or participation.

“For a public transaction,” tweets Bianca Wylie, “the Sidewalk negotiation has been hard to follow given the amount of secrecy, public relations, and strategic communications.”

Sidewalk offers a steady stream of persuasion and dissuasion, truth and half-truth, logos and websites, romance and realism, hands-on workshops and tangible showrooms. It also offers insufficient public consultations, “problematic” data governance, dense development plans, high-profile resignations, non-disclosure agreements, “black box” mysteries and mad dashes for public land, revenue and regulatory capture. Sidewalk is open and closed, visible and invisible, general and detailed, summer and winter, big and small, long and short. Sidewalk’s narrative simultaneously bombards the media and beguiles the democratic mind.

“How the dream is spun, how the promise is made, tells us a lot about the politics being sold,” writes Molly Sauter. “This is useful in modern smart city projects that often claim to be apolitical, as is the current fashion among the high-tech companies that design, promote, and sometimes build them. What politics do these projects deploy?”

Companies like Sidewalk yield power. They are political actors who privilege their own economic order, with their own lobbyists and their own business strategies and goals. As Sauter reminds us, “the stated goal of the Sidewalk Toronto project is to develop, through the extractive data-labor of residents [and] smart cities technologies for export by Sidewalk and Alphabet.”

As Evgeny Morozov puts it, “Google Urbanism” deploys “Alphabet’s data prowess to build profitable alliances with other powerful forces behind contemporary cities, from property developers to institutional investors”. As Maroš Krivý describes it, Sidewalk images portray a benevolent, happy and healthy life but they also “build investor trust”. Sidewalk Toronto’s extractive goal is clear; to trial private investment in data-driven urbanism, adapt to failure and then export its success beyond Toronto.

Trudeau agrees, in a way, claiming at the launch that “this will create a test bed for new technologies.” A test bed. A guinea pig. A lab rat. “A kind of giant real-world petri dish”, writes John Lorinc. Or, as Jim Balsillie puts it, “a colonial experiment in surveillance capitalism attempting to bulldoze important urban, civic and political issues”.

“Surveillance capitalism” sounds like something out of a conspiracy novel, but it’s underlined by Harvard Business School professor emerita, Shoshana Zuboff. Her recent book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, describes “a new economic order that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales”.

Many are concerned about digital surveillance, the extractive imperative, the promotion of privatization and demotion of democracy. Since Edward Snowden’s PRISM revelations of 2013 and Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2018, those fears are now grounded and find mainstream resonance.

Increasingly, democratic governments rally around the International Grand Committee on Big Data, Privacy and Democracy. Everyday, democratic citizens internalize the fear of being mined and look for ways to hide through self-censorship, email encryption, ad-blocking and private browsing. Many designers have even developed jewellery, hair styles and garments capable of evading facial recognition.

The stakes are immense, prompting us again to question: Why are journalists, art directors and editors so keen on Sidewalk handouts?

Do they lack visual literacy? Is there a general knowledge issue? Are there professional ethical issues? Are they too easily impressed by promises of collaboration and projections of optimism? Are they too industry compliant? Do they get briefed “on background” with sources dictating content anonymously and off-the record? Or, maybe they lack the cleverness to create alternative images? Is there a practical production issue?

With chronic consolidations, layoffs and scant reporting resources diverted to video, digital and debt servicing, it’s tempting to use free handouts, but a lack of budget is a poor reason for this journalistic lapse. Editorial independence is also at stake. Besides, any competent art director would know how to save money by working with open source image databases, nurturing young talent coming out of art school, or partnering with groups like Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism.

Too few news outlets take images seriously or take the opportunity to meaningfully challenge Sidewalk’s visual narrative, therefore laundering its private power and public relations in the process. There is some amazing investigative journalism, technology reporting and informed opinion on Sidewalk. More of it is needed. There also needs to be a careful read of power’s visual representations and a willingness to avoid amplifying them. Sometimes the first step in speaking truth to power is to stop reproducing it.

All collages by Michèle Champagne.