In 1977, George Plemper, a local school teacher, began photographing Thamesmead in south-east London. Devised by the Greater London Council to remedy the pressures of the post-war housing crisis, Thamesmead was a housing estate built to instil Londoners with a renewed sense of belonging after the Second World War. Capturing this transitional period of optimism, Plemper’s photographs show children and teenagers wandering across the town, socialising in local parks, playgrounds and swimming pools. In one image, we see four boys standing in front of a roundabout. Behind the roundabout, multi-story tower blocks and a row of stacked maisonettes stand tall with a calm, reassuring appearance. Despite the motion of the cars which circle the roundabout in the midground, the tenor of the photograph is one of permanence and stability. This is a patently brutalist urban landscape which appears as a visually ordered, structured and unified whole.

The anticipation that accompanied Thamesmead’s construction as portrayed in Plemper’s photographs was inseparable from the town’s architectural form. The town’s tall tower blocks and extensive network of overhead walkways were seen as indicative of “a kind of urbanism at the cusp between present and future,” as Stephen Babish has written. Before it had even been fully built, Thamesmead was already being heralded as “The Town of The 21st Century.”

The post-war utopianism that coalesced around Thamesmead’s emergence, however, quickly began to deteriorate. Planned transport links to Central London, including a bridge crossing the Thames, never materialised. Consequently, the town became a concrete island within which residents were severed from the rest of the city. For early residents, there was also a stark disjuncture between how Thamesmead was being portrayed and what they encountered upon arrival, which was not a fully constructed town but a nascent landscape pervaded by loose debris, barbed wire, concrete dust and half-completed buildings. A year after the first residents arrived, still no shops had opened, and a promised town centre was nowhere in sight.

These issues were only compounded by a shift that was beginning to reverberate across the landscapes of the British media following the 1972 release of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Infamously filmed in Thamesmead, the film was labelled as one of the most controversial works within the history of cinema. Three days after its release, the British film critic Peregrine Worsthorne decried the film as “Muck in the Name of Art” in a piece for the Sunday Telegraph. A month later, the Philadelphia Daily News published the headline “Stop the Clock! Kubrick’s Loose,” denouncing the film’s “nauseous, revolting, despicable depiction.” As these narratives continued to accrete, Thamesmead’s place within the cultural imagination experienced a fundamental upheaval. Increasingly, what the town appeared to resemble was not so much a place inhabited by real people but rather, one “defined by its fictionalisation,” as Owen Hatherley has observed.

If the notorious droogs in Kubrick’s film began to crystalise a sense that Thamesmead’s brutalist architecture was the incubator for violent, psychopathological tendencies, Margaret Thatcher’s political ascendance towards the end of the 1970s elevated the purported connection between Thamesmead, crime, and physical brutality to the state of a ubiquitous fact. Capitalising on the growing sense of unease that was beginning to permeate the media’s views towards brutalist architecture, Thatcher contended the post-war welfare state was producing crime-ridden environments plagued by cold, dehumanising walkways and tenebrous underpasses. The result was a new “British aesthetic conservatism,” as Inez do Coo has put it, which argued the very materiality of concrete had an inherent coldness that ‘seeped’ into the bones. In this context, municipal socialism was pathologised as a kind of contagion that was seen to proliferate architecturally. For Thatcher, what this necessitated was a swift and decisive shift in Britain’s political economy away from the welfare state and social housing towards private ownership and the free market. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the following decades saw Thamesmead’s development stunted by the rampant escalation of neoliberal capitalism.

In 2014, Peabody—one of the U.K.’s oldest housing associations—purchased the Thamesmead estate and embarked upon a £1.5 billion regeneration project, which is looking to resuscitate the town from decades of disinvestment. “By 2050” notes John Lewis, the Executive Director of Peabody, “Thamesmead will have doubled, creating a denser, livelier, more social place to be.” Not only will this stimulate “new waves of investment and growth,” it will also purportedly bring into motion a new, revitalised “Thamesmead that stands apart from anywhere in London.” In marked contrast, then, to Thatcher’s pathologisation of Thamesmead as a kind of architectural monstrosity, Peabody’s regeneration is situating itself at the opposite side of the ideological spectrum as it presents Thamesmead as a town with seemingly unbridled potential.

New transport links have already placed the town within 11 minutes of Canary Wharf. Thousands of new homes will allegedly be built. The regeneration’s underlying intentions and the related question of who the town is being redesigned for, however, remains fraught with tension. Glancing at Peabody’s 7-phase masterplan for the revamping of South Thamesmead, for example, it is clear the organisation intends to reduce the proportion of affordable housing stock over time. A similar trajectory appears to be underway at Thamesmead’s Lesnes Estate, which Peabody are hoping to raze in favour of a new housing complex that will provide 1,950 homes only 307 of which will be affordable rent and 61 social rent. What seems to be emerging under the guise of this multi-billion pound regeneration project, then, is simply “another cookie cutter chunk of could-be-anywhereism” as the architectural critic Oliver Wainwright has argued. This is not a project intended to improve the everyday lives of residents already living in Thamesmead. It is instead a regeneration project that is actively orienting itself towards a new, incoming urban elite.

If Peabody’s regeneration symbolises a kind of speculative utopianism that stands in contradistinction to ideologically conservative perspectives which have viewed Thamesmead as an urban monstrosity, then Owen Hatherley’s contention that “Thamesmead is a habitually romanticised or demonised place” certainly holds true. The town continues to vacillate between extremes. For some it is a place afflicted by bleak, overbearing architecture. For others, it is a place brimming with novel possibilities. An ambivalent middle ground, however, can be discerned when we pivot away from these two ideological extremes and instead look towards the forms of cultural output that have been produced by those actually living in Thamesmead. Here, we are confronted with entirely different perspectives rooted not in the ideologies of a political elite nor the aspirational visions of property developers, but in the everyday experiences of local residents. In this context, the local Thamesmead artist Almudena Romero and her 2019 series of photographs About The Thamesmead Chapter might be considered emblematic.

Romero’s collection comprises a series of fibre-based silver gelatin prints that were created on traditional black-and-white photography paper. Through a unique process of manual development, Romero transmuted the unexposed silver in the paper—the highlights of the image—into a kind of a reflective silver mirror. On the one hand, this drawing of the silver nitrate layer that was already embedded within the paper up towards the surface “mimics a hallmark of brutalist architecture: the exposure of raw materials,” as Romero puts it. This mirror effect, however, also imbues the collection with a pensive, inward-looking tenor. “I create these paper silver mirrors to echo my personal experience of living in Thamesmead” says Romero, “an introspective and self-reflective journey.” She continues, further documenting how her time in Thamesmead has fed into her style of aesthetic experimentation:

“I moved to Thamesmead in 2018 as part of a redevelopment scheme inviting 40 artists to reside in the area. In exchange for affordable housing, we were encouraged to contribute to the creation of a more cohesive local community through active participation in forums, workshops, festivals, and other art and community initiatives. However, the work-oriented urbanism of the area—with its lack of cafés, cinemas, theatres, and other social spaces—alongside a local history of marginalisation and social exclusion, and the instrumentalisation of community-building for property revalorisation by the housing company, complicated this endeavour. This series includes large-scale works and abstract image-objects embodying the disorienting forms and scales of Thamesmead’s blocky brutalist architecture, as well as the equally confusing contradictions of housing schemes that both support artists and fuel gentrification for profit.”

We can detect here a set of social and political critiques concurrently feeding into and emanating out of Romero’s collection. The first pinpoints a rather forced and contrived approach that was adopted by Peabody within their regeneration, which aimed to draw artists into the town through the innovative use of economic incentives; namely, affordable housing. These artists were then encouraged to participate in a host of forums, workshops and festivals to stimulate local community activity, as if the cultural fabric of space is something that is both passive and inert, waiting to be activated at the behest of property developers. Of course, Romero has to some extent been a beneficiary of this scheme, yet she remains reflexive of her own position within Peabody’s “instrumentalisation of community-building for property revalorisation”; something she perceptively connects to wider local histories of marginalisation and social exclusion.

Indeed, Thamesmead has a long and complex history of exclusion and violence. During the 1980s and 1990s, the town operated as a refuge for British National Party (BNP) supporters and in 1991, the town became the site of one of the most abhorrent murders in recent history, when 15-year old Rolan Adams was surrounded by a group of 15 white ethno-nationalist youths and stabbed to death. Shortly after, local BNP supporters paraded across the streets of Thamesmead with Union Jack flags celebrating the murder. Weeks after the murder of Adams, Orville Blair, another Black youth, was murdered in the town by a white gang.

In this context, there seems to be a temporal critique embedded within Romero’s photographs. Not only does she critique Peabody’s use of community building as a tool for property revalorisation, she also identifies a certain “work-oriented urbanism” entirely indifferent to the town’s fraught histories. In doing so, Romero exposes the cultural amnesia that pervades Peabody’s regeneration, laying bare how the ongoing attempt to usher in new heavily engineered cultural futures remains oblivious to the fact that certain cultures have always existed, and indeed dominated, in Thamesmead. It is precisely this clash between two strands of consciousness—one, historically apathetic, the other, engaged—that positions Romero’s series of photographs within the remit of an ambivalent realism; ambivalent, because it is a collection suffused with a myriad of tensions and “confusing contradictions.”

Perhaps the most interesting element of Romero’s photographs lies in their refusal to erase these messy tensions and contradictions. Instead, her collection looks to dwell within a space of ambiguity. Non-figurative methods are deployed to portray what she describes as Thamesmead’s “disorienting forms and scales.” High contrast-landscapes and abstract-imagery are also mobilised to convey “Thamesmead’s blocky brutalist architecture.” And yet, what is most striking about the collection is not so much its depiction of Thamesmead’s urban form, but the overwhelming sense of absence that appears to linger in perpetuity. Indeed, traversing Romero’s collection, we find no human bodies, no animals, no forms of movement that indicate any signs of life. Thamesmead is therefore depicted through the prism of a strange “labyrinthine urbanism” as Romero puts it, entirely “devoid of… presence.”

This recurring, almost jarring absence cuts against the grain of Peabody’s speculative utopianism. After all, this is a town that is undergoing a multi-billion pound regeneration project. The property developer’s suggestion is not merely that this will be a new, reinvigorated town after the regeneration, but that it will be London’s new town. Clearly, Thamesmead is being allocated a certain degree of exceptionalism. Romero’s collection, however, creates an impression that runs counter to these anticipatory currents. The Thamesmead she depicts is not on its way to becoming the capital’s new iconic centrepiece. It is, instead, a town that appears to be grappling with a fundamental failure of presence. There is of course a certain irony here. Despite the biological metaphor of regeneration that has been deployed by Peabody, the ongoing redevelopment seems to be stultifying the town, hollowing out all character, vitality and life.

For all this, however, two dominant images of Thamesmead stalk the cultural imagination today. The first, positioning the town as an urban monstrosity beset by imposing architectural forms, is “expressed in an habitual past tense” as Raymond Williams might have put it. The second, portraying the town as an emerging hub in the heart of London, suggests Thamesmead is en route to a new kind of futurity. In both instances, what the town resembles is not so much a place experienced and produced by everyday residents, but an imaginary landscape that can be forged, distorted, and reconstructed at will. Evidently, the age-old colonial doctrine of terra nullius or no man’s land still holds sway.

Interestingly, however, this is being met with increasing opposition. Throughout 2023 and 2024, a spate of protests saw local residents cover the town’s walls with banners and slogans that called on Peabody to “take profit out of housing.” Some residents denounced the housing association as a “greedy and money-loving” organsation who “couldn’t give a fucking toss” about local people. Others, adopting more confrontational means, occupied the Lesnes Estate which was being lined up for demolition. Staying put as they called on the London Mayor Sadiq Khan to intervene in the planned demolition, the protest—cutting against racial, gendered and age-based lines—illuminated a radically intersectional refusal to remain passive to the intensifying pressures of the market. As one resident who took part in the occupation put it: “we’ve got no intention of leaving.” Another described her experience of spending a night in the estate: “tonight I am staying at the occupation … we have our sleeping bags and duvets and are ready to sleep.”

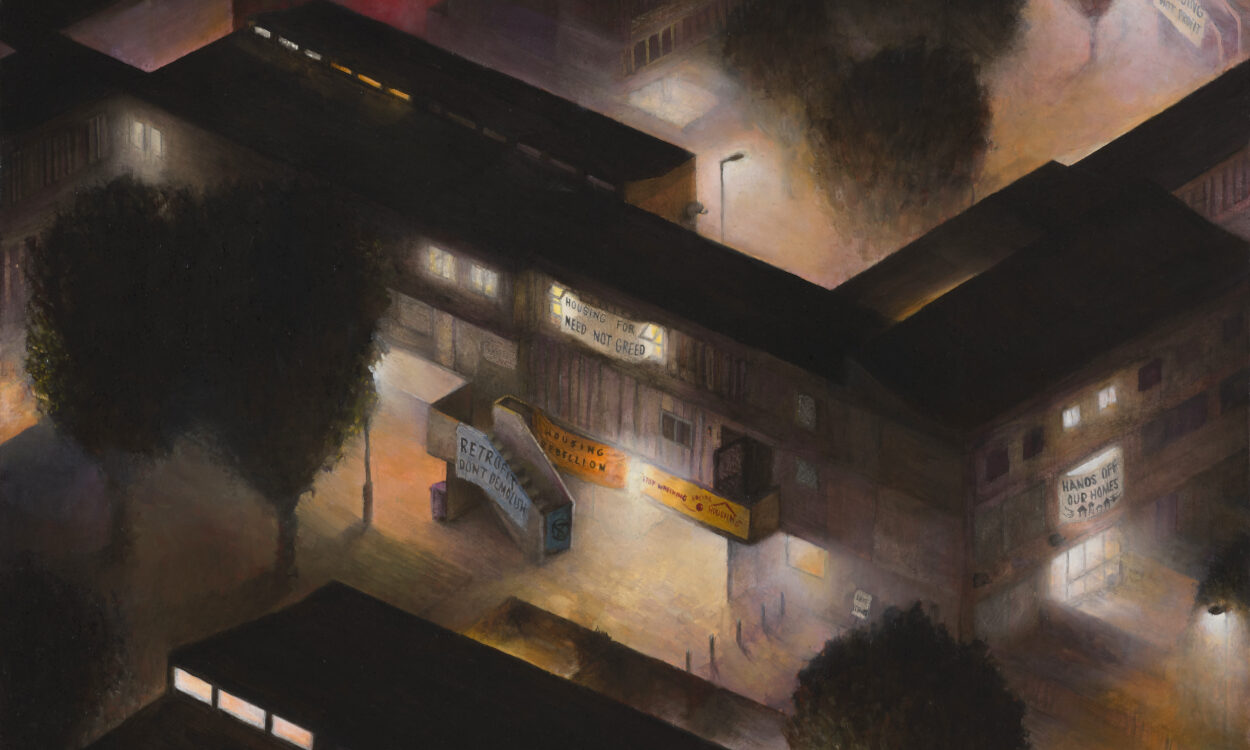

Dedicated to the occupation, the London-based artist Lawrence Brand’s 2024 painting HOUSING REBELLION OCCUPYING THE LESNES ESTATE captures this revolutionary structure of feeling. In the painting, the banners that lined the wall of the Lesnes Estate can be seen with slogans demanding Peabody “stop wrecking social housing.” Compositionally, the spaces in and around these banners form the brightest within the painting, radiating beams of light that jostle against the brooding night sky which hovers above. If the encroaching darkness signifies Peabody’s regeneration which is increasingly throwing residents into worsening states of precarity, the lighter sections surrounding the occupation and its provocative banners attest to a contrapuntal current of utopianism; one that runs counter to Peabody’s speculative utopianism. Here two banners that occupy the centre of the painting—calling for a “housing rebellion” that prioritises “housing for need not for greed”—are particularly striking. Clearly, these banners envision an alternative future for Thamesmead predicated on use, rather than exchange, values. Perhaps, however, we can also detect a provocative model for an entirely different kind of city—a decommodified London which might, finally, coalesce around the needs and desires of those whom the late Sly Stone once called everyday people.