This article is part of the FA special series Everywhere Walls, Borders, Prisons.

Tunde’s danfo slows to a crawl on the narrow stretch between Orile and Mile 2, inching towards yet another checkpoint. Ahead, a rusted STOP sign leans against a tire. Around it: warped planks, loose sandbags, and a barrel blackened from fire. A small group of uniformed officers lingers beneath a torn umbrella, motioning drivers to halt with a lazy wave. It’s a makeshift barricade, one of dozens scattered across working-class Lagos, where informal architecture stands in for official infrastructure, and informal payments replace policy enforcement.

Tunde hands over a crumpled ₦200 note through the window without protest. The officer barely nods before eyeing the next bus. Behind him, a black SUV glides through untouched. The officer doesn’t blink. On Lagos roads, legality bends around hierarchy. This is not just about traffic stops. It’s about how cities silently decide whose time, money, and movement matter — and whose can be taxed, delayed, or denied.

Checkpoints in Lagos don’t look the same everywhere. In Ajegunle or Mushin, working-class neighbourhoods, they’re built from rubble, charred tires, or fencing wired together by vigilantes or community guards. In wealthier enclaves like Ikoyi or Banana Island, they take the form of steel gates, CCTV, and uniformed private security. What they all share, however, is a deeper purpose: control of space, of movement, of class.

Danfo drivers, commercial bus drivers in Nigeria, prevalent in Lagos, are known for their bright yellow minibuses and chaotic driving style. Danfo drivers like Tunde are the most frequent targets. Their vehicles are stopped, searched, and fined for invented infractions. Bribes are routine; impoundments are common. Meanwhile, private car owners, especially those in new SUVs, often coast past with a nod or a waved greeting, unless something about them seems out of place. For working-class drivers, each stop is not just a delay, it’s a loss. Fuel, conductor wages, union fees, and owner dues already eat into earnings. Add checkpoint bribes, and many close the day in debt.

What begins as a simple ride becomes a daily gauntlet. And each checkpoint passed, each ₦500 (0.32USD) handed over, reaffirms what Lagos has become – a city where mobility is less of a right and more of a privilege, rationed out by uniform, income, and influence.

In Ajegunle, just past the third checkpoint on a weekday morning, Tunde’s danfo slows again. Uniformed officers lean against rusting barrels. The delay is minor, but for the passengers, market sellers, construction workers, factory hands, it’s yet another invisible tax on their time.

The damage isn’t only in delays. It’s in lost wages, missed deadlines, and mental fatigue. On the Lagos–Badagry Expressway, traders report checkpoint clusters turning 90-minute commutes into ten-hour gridlocks. Elsewhere, tricycle drivers say they’re delayed 20–30 minutes at each checkpoint if they can’t meet the ₦200 demanded by officers.

Checkpoint extortion in Nigeria is not a recent phenomenon. By the late 1990s, it was an institutionalized practice embedded within policing. Reports from that era describe senior police officers allegedly setting daily “returns” targets for rank-and-file, demanding ₦1000 here, ₦2000 there from drivers in cities such as Port Harcourt and Lagos. In 1998, Inspector General Ibrahim Coomassie publicly ordered the dismantling of all police roadblocks, citing widespread corruption and abuse. However, this directive was never meaningfully enforced and became part of a recurring cycle of performative crackdowns.

Subsequent Inspector Generals echoed similar directives. In 2015, Solomon Arase again called for the dismantling of illegal checkpoints, but by then the extortion system had become deeply entrenched and too lucrative to dismantle. Corruption scandals like the 2005 early retirement of former IGP Tafa Balogun, accused of embezzling billions partly from police operations, including road extortion, underline the scale of the problem. Crucially, this system extends beyond the police. Multiple agencies, including Lagos State Environmental Task Force (LASTMA) and Vehicle Inspection Officers, operate overlapping jurisdictions. This deliberate bureaucratic overlap creates confusion and competition, generating multiple points of extraction from motorists. Tunde’s experience of being stopped by three different agencies within a single street segment exemplifies this chaotic, profit-driven network.

Every lost hour is a deducted wage, a missed shift, or a full day ruined. For danfo drivers, it’s fewer trips and smaller payouts. For traders, it’s less time at the stall. For parents, it’s a walk through the dark. And for Lagos’s poorest neighbourhoods, it’s a system that ensures progress must wait for permission, or payment.

Tunde might return his danfo by 10 pm, but what he keeps is barely a thread of the hustle. The average take-home from a full Lagos shift is ₦7,500 (6.91 USD). Now subtract:

- ₦500 for union dues

- ₦500 for fuel (or ₦10,140 if it’s diesel at ₦780/L)

- ₦1,500 to pay the conductor

- ₦5,000 for the bus owner’s daily remittance

That leaves ₦0. And that’s before the bribes. The real losses begin on the road, ₦200 here. ₦500 there. Checkpoint after checkpoint, stop after stop—Tunde pays.

To police.

To LASTMA.

To touts.

To agberos, the bus stop touts in reflective vests with no badge, no office, no oversight.

Across Lagos, danfo drivers report spending ₦3,000–₦4,000 daily on informal levies, extorted not for any infraction, but for daring to work. One Oshodi driver made ₦6,300 (3.98 USD) in fares. He paid ₦7,000(4.42 USD) to fuel sellers and street taxers. He ended the day in debt.

Yet, most danfo drivers return the next morning. Not every day ends in loss, some days yield just enough after bribes and operating costs to feed their families or pay rent. Other days, however, are pure red ink. The unpredictability offers a gambler’s hope. Many drivers lack formal education or alternate livelihoods, so quitting isn’t an option. They endure day to day, hoping the next ride brings relief, not ruin. “If today bad, maybe tomorrow go better”.

In January 2022, the Lagos State Government under Commissioner for Finance Dr. Rabiu Olowo introduced a “unified ₦800 daily levy” hoping to reduce the myriad of levies down to a single charge. Yet it failed to stem the bleeding, with union officials saying drivers still pay duplicated charges across routes, often in cash. The average danfo now forks out over ₦292,000 (184.28 USD) a year and still suffers continual harassment.

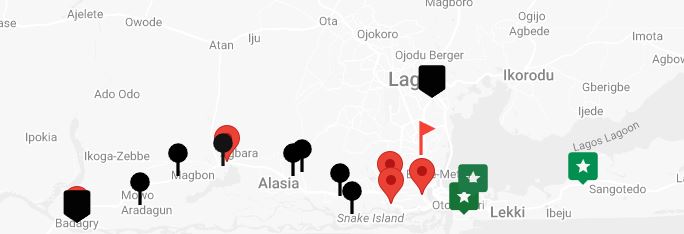

Across the city’s working-class transit corridors, checkpoints multiply like viral clusters. From Mile 2 to Apapa, over 50 illegal roadblocks choke the route, according to The Guardian. From Mile 2 to Seme, there are 52 more, reports Ships & Ports. The Badagry Expressway, meant to boost trade, has become a gauntlet of 30+ extortion points before even reaching Sunrise Bus Stop. COMTUA (The Council of Maritime Transport Unions and Associations), the truckers’ union, maps the chokeholds in chilling detail. Ajegunle, Amuwo Odofin, Iyana Iba, Abule Ado, Morogbo, Oko Afon, Igbo Elewe, Sultan Beach — every mile crawling with police, NDLEA, customs, FRSC, VIO, LASTMA. By early 2025, despite federal orders capping checkpoints at four, reporters counted 21 stops between Badagry and Seme alone (15 miles).

Meanwhile, if you cross the bridge, the story changes. In Ikoyi, Victoria Island, Lekki — checkpoints vanish. No daily police roadblocks or roadside harassment. When they appear, it’s a festive patrol or VIP convoy, not open-air tollbooths demanding ₦500 notes. It’s clear that there is a class divide in where these checkpoints appear.

This is no accident. Analysts and civil society observers agree, Lagos enforcement is spatially coded. Poor neighborhoods get policed, whilst wealthy districts glide through. A civic report by freemuse states plainly, “Checkpoints are feared, and they appear mostly in slums or highway bottlenecks”. The IGP admitted, “Between Seme and Mile 2, we have over 10 checkpoints. They’re damaging our image”. But there are no checkpoints on Lekki-Epe and none on Banana Island. The result is that workers from Agege or Ajegunle navigate daily extortion gauntlets just to reach jobs in Victoria Island. Goods trucked from Badagry arrive late and expensive. Commuters reroute, delay, or pay up. Meanwhile, SUV owners in Ikoyi glide past, untouched. This is urban apartheid by infrastructure, invisible gates made of uniforms and barricades. One half of Lagos gets roadblocks, whilst the other half, a clear lane. The city’s divisions don’t just map onto where checkpoints stand, they shape how those checkpoints look and function.

In working-class neighbourhoods like Ajegunle, Mushin, and Somolu, checkpoints aren’t built by the state, they’re improvised by residents. Faced with violent robberies and a lack of official protection, communities create their own barricades using tires, broken concrete, or wooden planks nailed into fences. At night, vigilantes guard intersections with torches and sticks, lighting fires to signal danger and keep strangers out. These are neighbours trying to survive without help from the system.

In contrast, across Lagos’ major highways, Apapa-Oshodi, Lagos-Badagry, Ikorodu Road, it’s the state that controls mobility. Here, police, customs, and paramilitary agencies erect official checkpoints: concrete cones, spike strips, patrol vans, yellow barricade poles, faded “STOP” signs. Some sit beneath tarpaulin tents, flanked by armed officers.

Despite the appearance of order, the intent often mirrors that of the vigilantes, control, not safety. Premium Times uncovered cases of police impounding buses and demanding bribes for their release. At Cele Bridge, an extortion hotspot, officers routinely flag down trucks and danfos, not to inspect but to extract. The tools may be official, but the motive — profit — is the same.

Where Ajegunle builds fences from fear of armed robbery and state neglect, Banana Island installs fortresses from wealth. One neighbourhood shouts “no go after 8 p.m.” on scrap wood. The other closes streets behind biometric access gates.

Checkpoint architecture becomes class performance.

Same city.

Different rules.

Different tools.

In between lies a collapsing middle ground where police and vigilantes sometimes share turf. In Mushin and Somolu, locals fund security gates while police “patrol” nearby, a quiet partnership blurring legality and self-help. As one Guardian report observed, nearly every Lagos street now has a fence, a gate, or a post. Whether a boundary or checkpoint is made through official or unofficial means, their end use is the same and further exacerbates the tensions in class and the differences between neighbourhoods across the city.

Twenty years ago, such checkpoints were rare. Today, Lagos runs on them. Over the past twenty years, Lagos’s explosive growth in population and commerce led authorities to install more checkpoints under the guise of “visibility policing” to curb armed robbery, kidnapping, and smuggling. In practice, however, weak enforcement of disbandment orders and the prospect of unofficial “returns” have allowed roadblocks to multiply, often rebranded as “stop-and-search points”. Local commanders and political figures sometimes tacitly endorse new checkpoints to address perceived spikes in crime or simply to boost income, while rank-and-file officers routinely operate “unauthorised” stops for extortion. Despite periodic directives to streamline or remove illegal checkpoints from the government, many reappear shortly afterwards, reflecting institutional corruption and minimal accountability.

Tunde, a danfo driver of eight years, sums up the checkpoint routine bluntly: “Every stop na cash-and-go. No paper, no search, just stretch hand, collect, move”. Investigations reveal billions of naira flow from road users into a shadow “returns” system, where junior officers pay up the chain in exchange for highway postings.

There’s no official marker announcing extortion, but Tunde understands the unspoken rules. The moment he reached Ojuelegba bridge, two officers materialized like actors on cue. One scrutinized him closely; the other barely glanced. The real question wasn’t whether he’d pay, but how much and how quickly. What most motorists, including Tunde, don’t grasp is the full trajectory of that ₦500 note, how it flows upward through a hierarchical network.

Attempts at resistance surface sporadically but rarely dismantle the system. In 2021, commercial drivers in Oshodi and Alimosho organized mass protests against extortion, blocking roads and refusing passengers. They accused both police and task forces of seizing buses and demanding under-the-table payments. Despite government promises to investigate, drivers resumed work under the same oppressive conditions, signalling institutional tolerance for ongoing corruption.

And in some parts of Nigeria, the cost has been fatal. In December 2020, a commercial driver was shot and killed by a policeman in Rivers State for refusing to pay a ₦100 bribe. The incident echoes daily standoffs Lagos drivers face at similar checkpoints. Outrage in Rivers State was immediate, youths in Rukpokwu and Rumuodomaya set bonfires, blocked roads, and clashed with police, demanding justice after the tricycle operator’s killing in December 2020. Spontaneous protests erupted around Port Harcourt International Airport for hours, forcing the arrest of an officer and drawing national attention. In Lagos, drivers and commuters likewise organised protests in Iyana-Ipaja and Badagry in 2020 that mirrored earlier resistance in Alimosho, sparked by extortion, harassment, and the daily ₦100–₦200 checkpoint tax.

The widespread anger is not isolated to drivers. The #EndSARS movement in 2020 exposed decades of police brutality, extortion, and checkpoint violence, culminating in national and international attention. While protests targeted SARS, the rogue Special Anti-Robbery Squad, they effectively condemned the broader policing system. The government’s response was to disband SARS only to replace it with SWAT, demonstrating the immutability of institutionalized abuses. Tunde continues his daily commute carrying folded notes, one each for the police, the task force, and contingencies. The real violation is not legal infractions like expired documents but his perceived social status and lack of connections. This is the real architecture of control in Lagos: not law, but appearance, class, and leverage determine who is stopped and who passes freely.

The truth is, every naira exchanged at these checkpoints is a small thread in a vast web, woven tight with power, fear, and survival. It’s a currency of control, invisible but heavy, passed hand to hand, pocket to pocket, shaping who moves and who stays stuck. On every road, a lazy wave halts you at a makeshift barricade, one of dozens scattered across working-class Lagos, where informal architecture stands in for official infrastructure, and informal payments replace policy enforcement. Like eba soaked in bitter egusi, this system is familiar, unyielding, and impossible to swallow whole—but still, it’s what millions endure every day. It’s a daily passage through a system that taxes not just wallets but dignity, a system where survival depends on navigating the invisible architecture of power. And yet, in that system’s shadow, sparks of defiance flicker—protests, viral calls for justice, community acts of resilience—reminders that even the deepest roots of corruption can’t choke out hope entirely.

So yes, the roads are clogged. The checkpoints, and their makeshift barricades, remain. But the story doesn’t end with Tunde shutting off his engine. Because in Lagos, the road is never just asphalt… It’s a battleground. Every ₦500 handed over asks who owns this city and who decides who moves? Tunde knows the answer, because he lives it every day. And if Lagos is a pot of egusi and eba, bitter yet sustaining, then people like Tunde are the fire beneath: relentless, enduring, and ready to boil over.