This article is part of the FA special series A City of Our Own

Imagine for a moment that you are a person who rides the subway to work on a daily basis. Imagine also having to walk to that subway in the morning and return home from it at night. Imagine this is a trip you have taken many times, and because this route is so familiar to you, you are aware of potential encounters that may take place along the way. So when you get up in the morning, there are decisions to make. Perhaps you will wear exactly what you want to wear, and this outfit reveals something of your body; your chest, your legs, your socially debated body hair. Perhaps this outfit — a short skirt, a collar, 4-inch heels — models your body in a light deemed by others (ads, tv, gossip, etc.) as sexual or deviant. Or, maybe, the outfit reveals an affiliation considered non-standard, such as a hijab, a kippah, or a mustache over a lipsticked mouth. Do you wear the selected outfit, the one you want to wear, or do you modify it? Neither of these options is a question of character but rather of strategy. Is your strategy invisibility, hypervigilance, or both? Do you anticipate protection?

The project of keeping women and queer people safe in public space is a complicated one, owing not least of all to the complex question of why we, as a society, believe that they need protection. When women and queer people report instances of abuse in public space, do the responses address the conditions of their vulnerability or merely characterize their identities as inherently vulnerable? When a person says ‘a man on the street followed me’, or ‘a teenager spat on me as I was waiting on a train platform’, or ‘he tried to put a hand up my skirt’, what does the redress for these experiences look like? Traditionally, it has been preventative surveillance, or if the perpetrator is found and the assailed party is believed, it might be incarceration. But these measures don’t necessarily make a space safer, nor are they capable of addressing all the threats of a public environment. However, the paternal approaches of surveillance and incarceration are the culturally normative response to insecurity. They offer the possibility of intimidation and vengeance.

Paternal protection assumes that, like a child, a woman or a queer person out in the world is naturally incapable of looking after themselves or that, no matter the context, they are a lure for predation.This assumption leads the paternal protector to both exact vengeance upon the perpetrator (if the report is believed) and to scold the assailed party: ‘do not go out too late’, ‘do not go out alone or in that outfit’, ‘do not go out in that part of town’, etc. This is how to stay safe, even if these precautions ensure women and queer people are barred from the full experience of public space. But, this list of precautions is often already the constant companion of any person who has experienced gendered violence. And vengeance does not prevent future violence or ensure safety in public space.

For those demographics that experience high rates of gendered violence, it is important and even liberating to talk about what makes them feel unsafe, what strategies they developed to keep themselves safe, and where they look for protection and support. Through a series of interviews examining people’s experiences in public space, Here There Be Dragons podcast has revealed the many little adjustments and maneuvers that residents use to keep themselves safe. They wear turbans instead of hijabs, they place their keys in easily accessible pockets, they do not hold their partners’ hand, they shout at catcallers, they avoid bright colours, or they put their heels on at work. In other words, they take precautions and are careful readers of their environments. However, in the cities where the hosts conducted the interviews (New York, Paris, and Stockholm), the built environment is not always seen as an asset in the legislative response to public safety. Designed protections in the built environment are usually aimed at control and containment. Cities are quick to deploy anti-car barriers, fencing, security cameras, anti-homeless spikes, and other blunt technologies directed more at curtailing individual behaviors than making the space itself feel more welcoming or easeful. Furthermore, policing and surveillance of individual behavior often fall back on cultural stereotypes. Those who are culturally perceived as most vulnerable, people who present in a stereotypically feminine way, for example, are seen as most deserving of and subjected to paternal protection.

Sociologist Sara Farris and theorist Jasbir K. Puar’s concepts of femonationalism and homonatonalism are useful litmus tests for paternalistic safety measures that claim to fortify the rights of women and queer people. Initially framed to conceptualize certain national institutions’ use of queer and feminist movements to justify anti-muslim rhetoric, femo- and homo- nationalism, according to Sara Farris, “address the political economy of the discursive formation that brings together the heterogeneous anti-Islam and anti-(male) immigrant concerns of nationalist parties, some feminists, and neoliberal governments under the idea of gender equality.” Tying feminist and queer visions of safety to nationalism immediately creates a cultural hierarchy of behavior. It is a paternalistic surveillance approach that insidiously deputizes women and queer people of the most privileged classes (white, having the full benefits of citizenship, etc.) to further stigmatize marginalized members of their own communities. This approach severs the relationship between marginalized groups and the mainstream collective of feminist and queer movements, uses individual behavior as a greater threat than systemic oppression, and insists on using tools (e.g. state violence) that have long been wielded against women and the queer community.

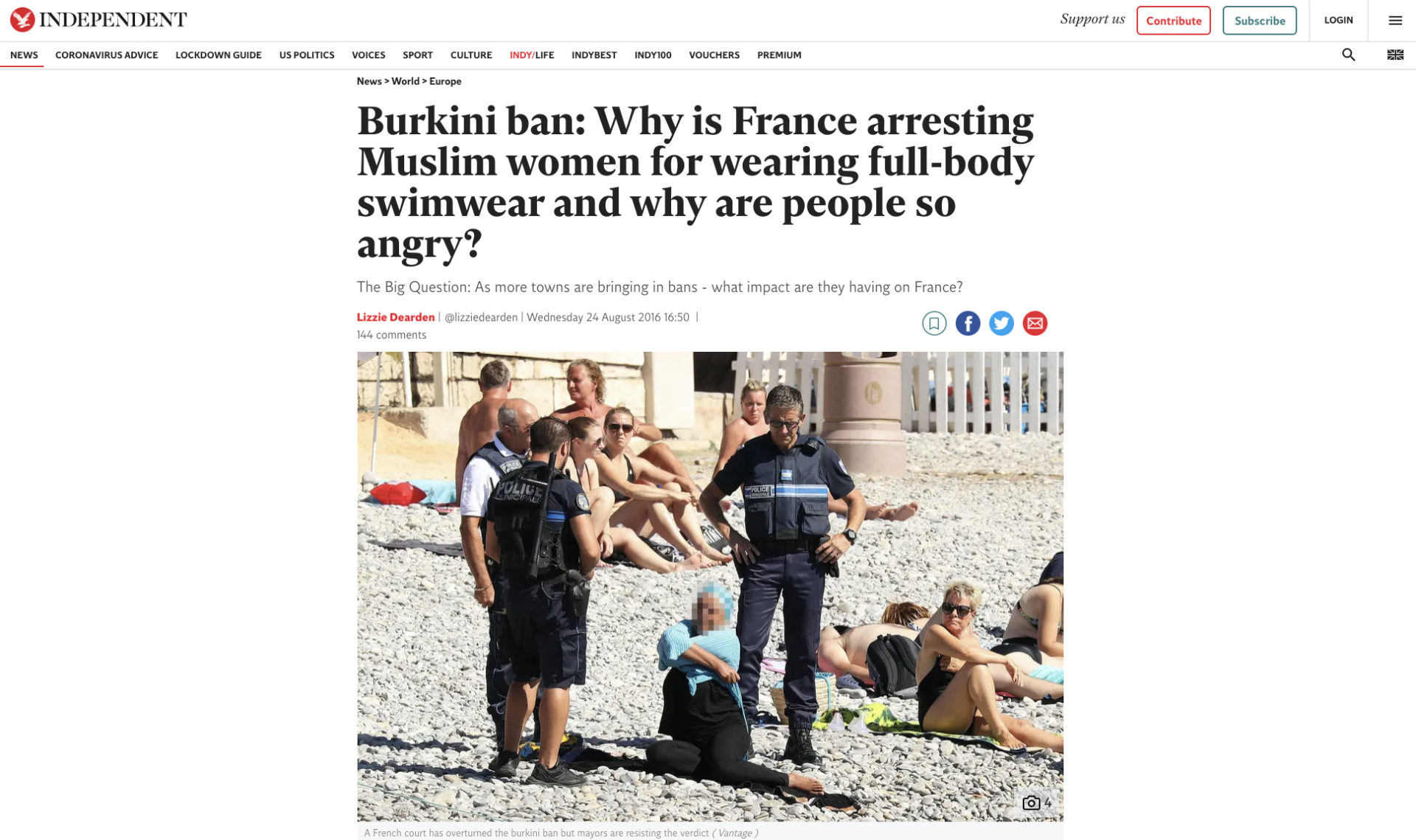

France’s 2016 burkini ban is especially illustrative of this strategy. After a terrible truck attack in Nice killed scores of people during the municipality’s Bastille Day celebration, a raft of policies swept the French Riviera, including the banning of full-body wet suits which observant Muslim women wear to swim. Local mayors used a broad spectrum of justifications, ranging from the protection of “public order” to a sudden concern about “hygiene.” To this, national politicians like Marine Le Pen, head of the far-right party Front National, and former socialist Prime Minister Manuel Valls, added the narrative of women’s rights, declaring, “France does not lock away women’s bodies,” and that the swimwear was an expression of an insurgent culture “based on the enslavement of women.” These policies led to real-world collisions, such as the image that came to define the burkini ban: an older woman kneeling on the beach surrounded by three local police officers as she removes her top. The top in question is not a burkini at all but rather a turquoise blouse matching her headscarf. Outside of the circle of officers, there are a number of women in one- and two-piece swimsuits looking on through sunglasses. By the logic of these policies, a publicly enforced stripping protected these on-lookers from cultures that would debase women.

Intimidating a woman into removing her blouse on a beach was the French state’s way of ensuring that French culture is seen not to pressure women into modesty. However, by singling out Muslim modesty specifically, the state makes it clear that this pressure is only a concern when the ordinance emanates from Islam. The state is not so concerned by the pressure a woman might face to wear a bikini and wax her legs for example. In the burkini ban and legislation like it, if the threat is given the face of Islam or another “other”, then vengeance can be exacted against it. Here, the agents of the state, the police, take on another role not just as law enforcement but as enforcers of cultural hierarchies. In the eyes of the state, this woman wears this blouse because she was forced to do so by a cultural practice they deemed anti-feminist. Their position intimates that the blouse must be forcibly removed to ensure not just her safety, but the safety of the women around her.

The various ways that state agents force people to conform to their cultural hierarchies has been well documented by sociologist Vanessa Barker in her article Policing Difference. According to Barker, rather than simply reflecting already given social relations, the police are “creative agents” in the production of difference. “It is in face-to-face encounters with the public” she writes, “that the police can impose a social hierarchy and unlike other social institutions… the police can back up their social ordering with violence. This makes them pillars of social production.”

These impromptu actions of the police are derived from creative interpretations of the law. The burkini ban policies, for example, do not mandate officers to surround women or force them to remove clothes; such decisions are made in the field. The police, in this instance, demanded a public stripping under the guise of upholding their traditions of cultural liberation. It is their lack of cultural empathy that creates the pressure to adhere to cultural norms and deputize those who do not oppose their biased expressions to uphold and mirror them. In urban space, replications of cultural hierarchies are a common side effect of an elastically interpreted policy that results in predatory action. These acts of harassment create greater insecurity for women and queer people.

Paternalistic security strategies focus on individual behaviors or incidents rather than the systemic oppression that women and queer people navigate on their own everyday. However, if we go to the root of the insecurity created by a violent incident, do these strategies address the core issue? Take for example, the spread of burkini ban occurred after the 2016 Bastille Day truck attack. It is difficult to imagine how the increased public scrutiny of swimwear addresses the insecurity caused by a horrific and public slaughter. When violence occurs and is reported (whether officially or through whisper networks), the effects spread beyond those directly involved. The violence from the truck attack was a ripple through the entire community of Nice, leading many to wonder whether it is possible for public space to be safe. On top of this worry, Muslim women, who are members of this same community, must also wonder whether the outfit they wear to the beach will lead police to strip them publicly. The truck incident and the security strategy that followed it were both ruptures of community relationships. These ruptures have not been repaired.

When systems of security concern themselves with the repair of all the relationships that violence destroys, this is what’s called “restorative justice”. Restorative justice is a concept that imagines a society where the controls of intimidation and vengeance are not required to maintain public safety. It envisions community as a series of relationships, and when there is a rupture in those relationships, it looks for ways to repair them. This system of public safety requires a broader range of stewards than just a police force. Rather, it relies on social workers, housing officials, healthcare workers, and yes, even architectural workers. This is a system that requires a greater imagination and engagement with the community than paternalistic security systems can provide, which means that the built environment can take a much larger role in public safety.

Although they may not directly call their work restorative justice, Paris-based urban planning consultants Genre et Ville take a very similar approach. The research of urbanists Chris Blache and Pascale Lapalud champions the idea that aggressive policing leads to landscapes of control and enforces the idea of constant insecurity. They work with women and queer people on solutions that foster a sense of legitimacy in public space. Referred to as “gender mainstreaming”, this approach encompasses a series of strategies endorsed in 1995 by the World Conference on Women, which advocated for the normalization of the spectrum of genders in public space. The idea of gender mainstreaming stems from the concept that the liberation of women and queer people has never been fully normalized. Their presence in public space is often still notable to the point of scrutiny. Genre et Ville takes an urbanist’s approach to gender mainstreaming by asking not just how to make women and queer people safe in public space, but how to make them welcome and comfortable. What might public space look like if the standard person imagined as the user was not a cis-gender man?

The Genre et Ville’s approach is not the suggestion that a pink paint job on park benches or rainbow crosswalks are sufficient design interventions, nor does it assume that design alone can create safety. Similar to systems of restorative justice, their research works with existing community relationships. They work with city residents to research how public spaces are used, and test how design and behavioral experiments might shift these uses to make these spaces more welcoming for women and queer people. These experiments or “actions,” as Blache and Lapalud call them, range from furniture design to programming, such as all-women soccer games that are part of late-night leagues and played in empty park spaces. These actions convey the hope that by creating alternative experiences and inviting women to use public space at all hours, other marginalized populations may feel safe enough to inhabit these spaces as well. While design is integral to the strategies of Genre et Ville, they are not the only ones performing experiments that push cultural boundaries. There are groups around the world attempting these shifts, like Girls at Dhabas in Pakistan that encourages women to spend time at tea counters mostly dominated by men, or the Mothers of Rinkeby that organizes Somali mothers to do late-night patrols in a northern neighborhood of Stockholm. These experiments operate to make women in public space a normal and unremarkable reality.

Gender mainstreaming can be seen as a security strategy. It can also be seen as an approach to restorative justice. The recent protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department have had cities all over the world seriously contemplating a different approach to public safety. One of these approaches has been to defund and dissolve police departments completely. Those unfamiliar with the concept of restorative justice may be wondering how it is possible to protect residents with no police force. The idea of abolishing police is not about leaving the matter of public safety unaddressed. Instead, it’s about putting the repairing of community relationships at the center of justice. It also expands the types of workers involved in keeping public peace. Rather than sending an armed police officer to do wellness checks, decrease homelessness, heal drug addiction, or deescalate domestic abuse, restorative justice would assign those cases to a number of other workers trained in handling them. Architectural workers can be among that number. Urbanists, planners, architects, designers, critics, construction workers, community developers, and the wide range of workers that shape space also have an important place in this system of public safety. But to step into that place, we, as a profession, have to accept that a vision for a safer and more equitable world is not only possible but also our responsibility.

Special thanks to Aleksandr Bierig and Ashley Simone for being generous insightful readers.