Newspapers and art critics celebrated La Maison Tropicale as a “modernist masterpiece” when the prefab house was shown in New York in 2007, subsequently displayed outside the Centre Pompidou in Paris and at the foot of the renowned Tate Modern in London in 2008. From intial plans in the 1940s/1950s to develop La Maison Tropicale on a large scale as modular housing, only three prototypes were eventually constructed. One of these protypes was auctioned for nearly $5 milllion at Christie’s in New York in 2007.

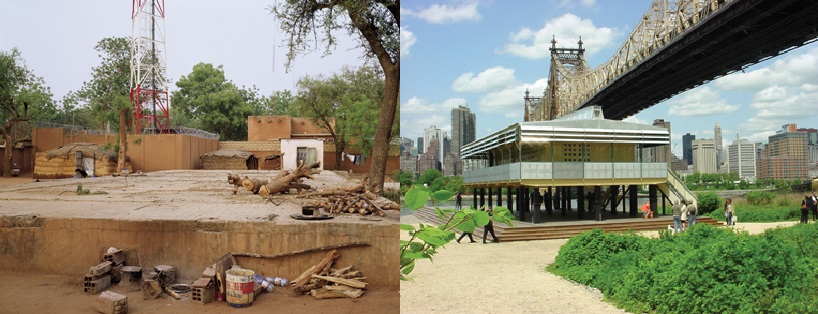

Displayed and admired as an art object in New York, London and Paris, one would not expect La Maison Tropicale in a state of abandonment in Niamey (Niger) and Brazzaville (Congo), a few years earlier. From its initial design to its recent rediscovery, La Maison Tropicale is a modernist house with a striking story.

Icon of industrial modernism

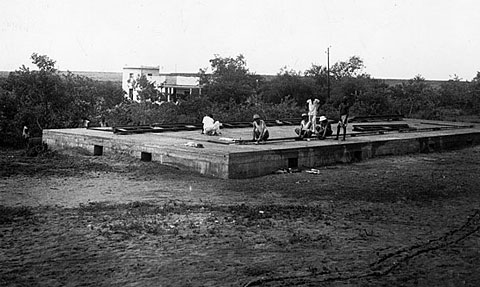

The story of La Maison Tropicale starts in the late 1940s, when French architect and designer Jean Prouvé designed the tropical house as a solution to the shortage of housing and civic buildings in the French colonies of West Africa. A large number of Maison Tropicales were planned to be built and transported from France to Africa. Therefore the houses had to be light and easy to assemble. This inspired Jean Prouvé to design a house that was made of prefabricated aluminum structures that could be easily constructed and dismantled. The framed structures of the house were also made to suit the tropical climate of West Africa, which led to Prouvé creating an inventive natural cooling system in the design. Due to its prefabricated components and innovative qualities, the Maison Tropicale became an exemplar of a modern standard type house. The functionality, rationality and standardization that characterized the project of the Maison Tropicale, make it an icon for industrial modernism.

Tool for social transformations

In many ways, La Maison Tropicale exemplifies modernist ideas about architecture. At the time Prouvé designed the house, architecture was seen as a powerful tool in bringing about social transformations. Rationalization and standardization in design and urban planning were thought to provide solutions to social problems. This idea merged with universalism; the widely held modernist belief in a universal human subject and a world in which cultural differences could be overcome. It was assumed that the discoveries of science could determine the needs of this universal subject and as such of the needs of humanity. Technical planners and architects were thought to be able to meet these needs and create spaces that would function equally anywhere. The idea of designing and constructing a tropical house for use in Africa, based on Western building techniques, is derived from this universalist philosophy.

Cultural dominance

Simultaneously, this universalist philosophy pointed to the fact that apart from a modernist design, La Maison Tropicale was very much a colonial object. It was assumed that European modern architecture was superior to local building styles and that French prefabricated housing was better suited to the climate than the local vernacular. Instead of using local building materials, the French promoted the use of aluminum, brick and cement. The French state-owned company Aluminum Français extracted raw materials from the West African colonies, which were refined into aluminum in France. This refined aluminum was subsequently used to construct Prouvé’s Maison Tropciale. Taken from West Africa, this aluminum was returned to West Africa as a different, finished product – a product that showcased the “technical superiority” of the French. The French colonials regarded their modern and innovative architecture as an expression of their superiority over the indigenous people, and therefore used it to exert cultural dominance. The French project failed. Instead of realizing the fabrication of La Maison Tropicale as a large scale solution as planned, only three prototypes resulted – built and placed in Congo and Niger.

A local perspective

In order to shine light on the local reception of La Maison Tropicale, African intellectual Mantia Diawara made the documentary Maison Tropicale in 2008. This documentary shows where the Maisons Tropicales stood before they were removed in 2000, and what the house meant to the local people in Brazzaville and Niamey. Locals were interviewed about their memories of the house and how they had experienced its presence. In the documentary it appears that a majority of the people felt a certain fear of the houses. They were seen as alien objects. La Maison Tropicale was completely different from the local building style, and the desired social interaction between the houses and African society did not occur. Its modernistic character – that receives limitless praise today – did not fit the African context.

Colonialism

Even though Prouvé probably aimed to make the Maison Tropicale to express the African way of living, once the houses were actually built and placed in Africa, they became colonial objects that supported the French colonial policies.

It can be argued that this modernistic project failed in two ways: it did not bring about the social change it intended to and it contradicted the idea of universalism, as the house – built according to Western modern architectural beliefs and using modern technologies – did not find success in every context – in this case, Africa. Above all other things it became a symbol of colonialism.

Interestingly enough, this fundamental aspect of the story of La Maison Tropicale was largely ignored by the press when the house was exhibited in the late 2000s. It was presented as icon of modernism, but not as part of a failed colonial project. The houses were renovated and are being maintained now, whilst they were in a state of dilapidation in Congo and Niger. La Maison Tropicale is praised in New York City, Paris and London by media and art admirers for its modernity, innovativeness, technology and industrial character. It has become a designer item – a product worth millions of dollars. As such, La Maison Tropicale illustrates how a design can become a fetish when its social life is neglected. Its renewed version is mainly seen as an art object and thus denies its multilayered history.

Ultimately, the original social function and colonial character of La Maison Tropicale are at the heart of its mobile existence. The fact that none of these aspects of the house are paid much attention to, in its Western reception, is all the more telling and signifies how history is written – and brings along many voids in its wake.