Listen to this episode and subscribe to the FA podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Overcast, or wherever else you usually get your podcasts.

In an article published in the Guardian earlier last year, Jon Henley reported on the state of the housing crisis in Amsterdam. The article’s title took a quote from one of the people that Henley interviewed: “Everything is just on hold”. For a lot of people in Amsterdam, everything really is on hold, as in, stuck where they’re living, usually with several other people, unless they’re a yuppie or coming from money or they somehow got a foothold on the housing ladder right before it got incredibly difficult to do so.

This is the situation for me, Charlie Clemoes, one of the Failed Architecture editors and host of this episode of the podcast. I’ve struggled with housing in Amsterdam for a while now, but something about having the situation reported on in the paper that my parents read back in England felt like a moment. After eight years living here, just about managing to fly under the radar in a series of cheap but temporary dwellings, the crisis properly caught up with me in late 2023, when, after moving back to Amsterdam after a year in Maastricht, I had to find a new place, which then brought me face to face with the open market, where there’s basically nothing available to anyone on a low income (which I have as a teacher and a writer and a cultural worker). I’ve known many people who have simply given up trying to live here. I almost did before, luckily chancing upon another antikraak (an anti-squat or guardian property in British parlance, where you look after an empty property by living in it, without normal tenant rights in return for lower rent.

It wasn’t that long ago, however, that Amsterdam had a lot of options for people on a low income. Indeed, more than that, Amsterdam has a rich history of quite bold experiments with social housing, the Amsterdamse School in the 20s and 30s, for instance, and also, more recently, the small-scale urban renewal projects from the 70s and the 80s. As my colleague Rene Boer pointed out in an article he wrote a while back for Failed Architecture, while these light grey and pink-yellow housing blocks are widely detested by the public, by dint of their perceived ugliness, they have remained relatively immune to the social housing sell-off in the rest of the city centre.

At the same time as these urban renewal houses were popping up, Amsterdam was also host to a thriving autonomous housing scene. In the podcast intro, I actually speak to you from my studio in Woonwerkpand Tetterode, a former type foundry that was squatted in the early 1980s and has since been turned into cooperative housing and workspace, where, if you can get one of the residential apartments, it’s still something like €500 for around 90 square meters.

It’s in this context of an accelerating housing crisis, in a city with a rich history of housing activism, that a group originally coming from another former autonomous space, Nieuwland, took advantage of a new housing law passed in 2015 that gave, for the first time in The Netherlands, the legal basis for founding a housing cooperative. They then began the process of becoming a cooperative, establishing a shared vision, successfully competing for the option to develop a plot of land made available by Amsterdam’s municipal government and raising the necessary funds to build on that plot of land. They broke ground on their new building De Nieuwe Meent (the New Commons), last year, and now, the building is delivered. At the moment of writing, the inhabitants are finishing their interiors in a collective DIT (do-it-together) process and in July 2025, they will move in for real.

The De Nieuwe Meent community designed their building with architects Time to Access (i.c.w. Roel van der Zeeuw Architects). Time to Access is a practice composed of Mira Nekova and Andrea Verdecchia, who will shortly be transferring their office to the dNM site, where they will also be running the cooperative space that dNM and different local initiatives will be involved in, which includes a cafe, bookshop, an event space, and a co-working space.

Earlier last year, I spoke to Andrea, just as De Nieuwe Meent was breaking ground, and partly because of the stress of my housing situation, it’s taken a while to get this conversation out, but here it is. We talk about, among other things, the history of cooperative housing, what it’s taken to get De Nieuwe Meent off the ground, what Time to Access does as architects of cooperative housing, and we end with some pointers about how to take up cooperative housing yourself.

Below is a transcript of the conversation.

Andrea Verdecchia AV: I’m one of the two founders of Time to Access, an architectural design office founded in 2019. We had a slow start because of corona, but we officially started in 2019. Me and my partner Mira Nekova have both lived and worked in the Netherlands for almost 15 years. We got experience at other architectural firms, where we mainly learned to deal with housing, sustainability and so on. And then we decided to found our own office to do things slightly differently and we used the occasion of De Nieuwe Meent, our first project and one of Amsterdam’s pilot housing cooperatives, to launch our own studio Time to Access. Time to Access and it is kind of like a call to action name. We wanted to give it a sort of urgency, so the time is now is something you hear at the housing protest, and it’s time to access something that is usually accessible for people. This is what defines us and how we try to work. We are specialised, as I said in housing, participation, and sustainability, this is what we do. At the moment, we have a couple of buildings under construction. One is De Nieuwe Meent and the other one is the CPO Baksteen in Amsterdam, Centrum Eiland, and we are developing other housing cooperatives. So all the projects we do, more or less, are variations of community projects.

Charlie (CC): De Nieuwe Meent was the place where I became aware that you were who you were. I knew you both before then, but that was the moment I was like “ohh cool Andrea and Mira are doing their own thing”, and it’s in this area that I’m personally very interested in, I suppose, cooperative housing. But De Nieuwe Meent has been quite a while in in the making, right, it’s sort of a five-year process or so, something like that, you said 2019, and it’s just broken ground. Do you want to talk a little about that process?

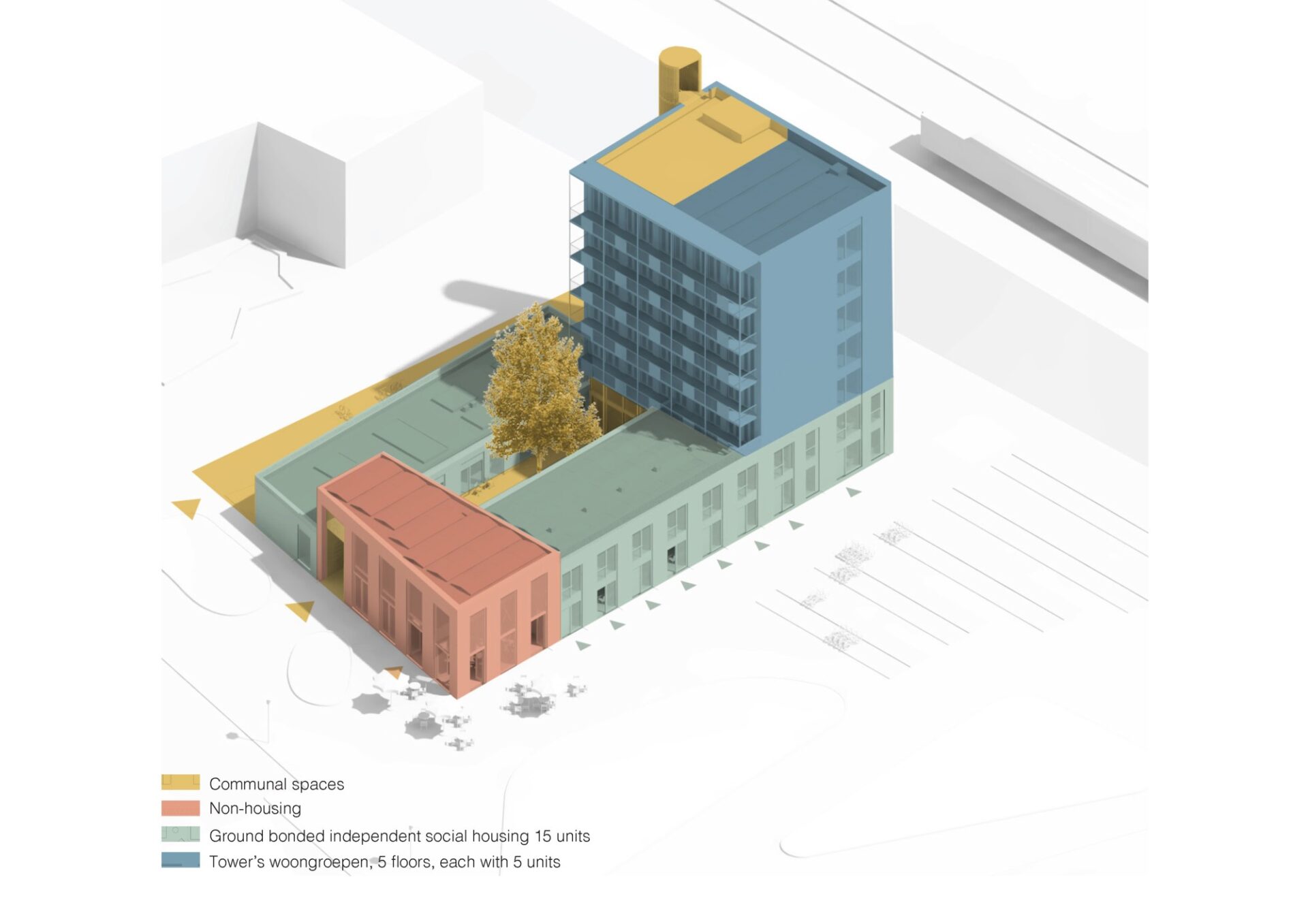

AV: So, De Nieuwe Meent is a housing cooperative in Amsterdam Oost. It’s going to have 40 housing units, and the project started in late 2018. So a long time ago. We had in the middle a lot of crises, corona, Ukraine, with all the construction costs going up, bank interest rates going up. So it was very difficult, especially financially, it was difficult. But finally, now we started building just two or three weeks ago and the building is going to be completed in one year’s time. So people will move in in one year. De Nieuwe Meent is a mid-sized building. There are some independent housing units, some living groups. It’s going to have a population of around 60 people, they share many collective spaces like a big kitchen, dining / chill out room, a multifunctional room, a guest house, laundry space, communal garden. It’s a very active community. They’re making a very nice building, in my opinion. Also very innovative, it’s built with a wooden construction, energy-neutral, so it ticks all the boxes, I think. We’re very proud of it.

CC: You brought it up and I think it’s a thing to open up a bit more: the role of the architect in this kind of development. Because the way you said that just then was quite interesting. Typically, the architects of the construction would be like, “we’ve made a good building, we’ve put together a good design”. But it felt very natural for you to say “they’ve made a good building”, you talked about the materials, but also the arrangement of things, so I am wondering, what is a cooperatively designed building in reality or in practice and what is the role of the architect in that?

AV: Yeah, I use the form “they”, “they made a good building”, because I don’t want to take credit for something that we did together. So I really appreciate the work that the community, the group, did and they really have all the merit, in my opinion. We were supporters of what they did. Housing cooperatives are a part of what in the Netherlands is called zelfbouw format. With this, there is an association of people that form a collective and they give a collective commission to one architect. This can be received by an architect in very different ways. It can almost look like a top-down project. No problem, you have your boundaries, the group is your client and you execute. But with Time to Access, we try to do it in a different way. We have our own method, where we try to set up a very intensive participation process and we co-produce the project together with the group. So there are some difficulties in this. Because the group is a collective client and is not a professional developer that needs to act as such, especially at the beginning, they rely a lot on your knowledge and the knowledge of other advisors and they learn by doing so, there is always this process of transferring your skills to the others and helping them to take decisions together and the people are involved from the beginning. We usually start with what we call a process design. So, even before starting with co-designing the building, we co-design the process that will bring the group and the building to life. And we do this with a lot of different activities, usually in workshops, sometimes just with some of the group, sometimes with the whole group. We do storytelling activities, we do card games, position games, we evaluate alternatives together. We talk about how the building looks, but also about the program, about sustainability aspects. We have also expanded our expertise beyond architectural design. We tap into process management, governance structures, finance etc. Sometimes we do these things, sometimes we do it together with other advisors.

CC: You said that. They had to turn to you to understand what it meant to be a developer, right? I don’t know if that’s a fair characterisation. But that means that, unlike a developer, who usually knows how to be a developer. I suppose the users are the ones acting as the developer in relation to you as an architect, but in a sense, you’re kind of having to learn what it means to be a developer as well, right?

AV: Yeah, that’s correct. If you take De Nieuwe Meent as an example, the initiators were a small group of people with a lot of community skills and they had their vision, they wanted to do cooperative housing. But they didn’t know how to do that practically, so we joined forces and we (Mira and Roel van der Zeeuw, our third partner for that project) brought our real estate development skills into the picture because we saw it from the inside, being architects of other projects. We knew what planning looked like, what the StiKo (Stichting Kosten, foundation costs) looked like. So we brought the technical expertise. The other people brought their community expertise and together we managed to do this project.

CC: Talking about the way that like creditworthiness works within development, typically the architect is insulated from that or kept away from decisions or limited by developers, because the importance of maintaining a profit margin is so important to a developer and an architect is a potential antagonist in that process because they’re trying to do something different. They’re not trying to make as much money as possible. And yet, that dynamic does seem to have some sort of utility, at least in the development paradigm we live in, in that someone else is dealing with the hard decisions. (I’m putting all of this in quotation marks). The developer maintains their creditworthiness and the architect wouldn’t be able to do that, yada yada, yada. But there is this loss of that hard-headed, boring, profit-oriented or profit maximisation-oriented developer in this process you’re involved in. So I’m wondering if that turned you into the hard-headed one or anything like that. How do you deal with the finance situation?

AV: The dynamics are very different. You are right. Normally, in commercial development (and we’re generalising here), the architect is presented with the construction cost goal. OK, so you need to make a building that costs €1800 per square meter or €2100 per square meter. And that’s it. With cooperatives, the process is very diffuse, and it is based on transparency. We are used to seeing the business cases, we actually collaborate in making the business cases and the business cases are also very different because the chapter on profit is not there. So you actually have a chunk of money, let’s say 10%, compared to a normal project, 10% that you can either cut out to reduce cost, or you can invest in other ways. From my experience with the groups, they still spend those 10% on quality: better materials, bigger spaces, higher ceilings. You name it. And, as I said, we are also part of making the business case. Always, at one point in the project, you are faced with cost optimisations. You see that your building costs too much and then you find ways to bring it back into budget. And how do you do it? Usually, you save on quality. Maybe you choose a cheaper brick or you do concrete instead of wood. But, for example, with De Nieuwe Meent, we work instead in the cracks of the business case. And yeah, we have been a bit creative. For example, we are not realising the photovoltaic panel systems ourselves, but we collaborate with another cooperative and we will buy the panels and lease cheap energy from this cooperative. So, your range of influence is much broader than the materiality of the building.

CC: There is something quite common sense about this approach and something illogical about the idea that, what the fuck, like 10% of the costs go to some outside investor. Because cooperative development is such a niche thing and also there is probably less money around for it because you know a big financial investor isn’t going to be interested in this because there is no element of profit, the funding sources a cooperative can rely on are limited. This brings us back to the question of how cooperatives come about in the first place. How is there even a history of cooperative development if that was always the case? But there is a history of cooperatives and there is a huge ecosystem of cooperatives. I used to live in a house that was run by Rochdale, and that’s a peculiar name for someone coming from England because it’s this small town in North West England and I looked into it and it’s because it’s named after the Rochdale Pioneers. The cooperative movement came from Rochdale. Basically, all the principles of the cooperative movement. But then you’ve got this huge housing corporation. And then, if you drill down even further, in the 2000s, the CEO of Rochdale was nicknamed Maserati Man. How does it go from having a cooperative origin, named after the cooperative cradle, to this huge corporation where the guy is in prison for fraud, and how do you see what you’re doing now within that history?

AV: Indeed. Now, if you go to seminars, it sounds like cooperatives are a new thing. But it’s absolutely not a new thing in Amsterdam, or in the Netherlands. The first cooperative housing association in Amsterdam was Rochdale, which was named after what you said. It was basically a group of workers who wanted to arrange their own housing facilities at the beginning of the 1900s. So at that moment, the city was suffering really bad housing conditions: no sewerage systems, very crowded apartments, working and living spaces in the same rooms, so they founded Rochdale. Soon they made their first building, I think at the very beginning of the last century. It became a popular format and there were many housing cooperatives for workers. Cooperatives also started to work with different housing standards: larger spaces, better hygiene. So the idea was also the same as the Society of Equitable Pioneers, the profit was shared, it was a not-for-profit project, usually developed close to the working facilities. Then what happened was that these cooperatives slowly scaled up and they became what is today known as housing corporations. Now, the housing corporations in the Netherlands are the bodies that provide social housing. When they became very big, they started to be regulated and also had fiscal incentives at the national level. The simple cooperative format was discontinued in national law. But in 2015, there was a new Housing Act. Where the state reintroduced the possibility of founding a housing cooperative.

CC: So before that, it wasn’t something that you could even do? You couldn’t say like “we are a cooperative and we wanna develop together”?

AV: For a long time, you could only do it informally, but there was no supportive regulation for it and if there is no supportive regulation, there are no people who give you money, for example. There was no city moving to reserve plots for you. So it was very difficult. But with this new housing act, the possibility came up again and Amsterdam is the first city that promoted an action plan. I think that was in 2018, with an active policy to make cooperative housing. And what does this policy include? They reserve plots for this format, they draw up conditions in which we operate and they set up a very important revolving fund, where the city of Amsterdam gives a loan of about 15%, which is based on the number of housing units you’re going to build. So there is this gap. The banks can give you credit up to 50% or 60%. Then, usually, you manage to bring equity for another 20% and the gap is covered by this loan. So the city of Amsterdam is the first one that did this and now there are other cities that try to follow, setting up regulations and so on, but they are not there yet. There are some independent cases and also other types of cooperatives. The so-called Beheer Cooperatie (Management Cooperatives), in which the living groups don’t own the building, but they rent the building collectively and manage it themselves.

CC: I think that’s what’s happening in Woonwerkpand Tetterode, where I have my studio, Stadgenoot are the actual owners of the building, but it’s a very arms-length relationship where the people in the community have a lot of freedom within the building. I imagine that happens quite a lot. I’m curious about this, being a bit more familiar with Tetterode: there it is an outcome of the historic squatting movement’s position of strength in Amsterdam and other parts of the Netherlands. But in a sense, they’re kind of a formalisation of the relationships that emerged in the 70s, 80s, 90s and am I right thinking De Nieuwe Meent has some roots, or at least some of the people are kind of connected to that legacy of squatting?

AV: Yeah. De Nieuwe Meent comes from another autonomous space in Amsterdam, which is actually a housing cooperative, founded by Soweto, called Nieuwland. And it’s also here in Amsterdam Oost. So yeah, there are some roots in the squatting movement or autonomous spaces.

CC: That leads me to another question: where are we at in terms of housing in general? It seems like there’s a clamour for a way out. We’ve reached a bit of an impasse in terms of the current private development model. I’m wondering if you could speculate on the question, why now, like, why has it emerged now? And what do you see, then, in the future for this sort of model?

AV: I think we we can look at this phenomenon at different levels. So first, like let’s say the big picture in Amsterdam, there’s a big shortage of housing and the regulators saw in the cooperative movement, this so-called third way, a way of differentiating and bringing up a new format that in the long run can be self-sufficient and provide a lot of extra housing units. So there is this third sector position between commercial developers and public housing or social housing in the Netherlands. And for the moment, it needs to be heavily financed, not subsidised, but financed with loans and so on. But there’s a big potential in the future because all these projects are based on credit and in 20-30 years time they break even and they start making a profit. But by legislation, they cannot make a profit, so the cooperative members keep paying their rent and these extras will go back into fueling the cooperative system. So think of a project of De Nieuwe Meent, with 40 houses at social rent. In three years, they could get €1,000,000 in rent. Part of this rent will go back into maintenance, collective activities for the community, some care for the members and so on. But most of it will be reinvested in projects for the neighbourhood or into different new housing cooperatives.

CC: It’s kind of like a virtuous cycle, right? Eventually, it will grow and grow and grow.

AV: Indeed, so now for this first project, it’s very difficult because they cannot really count on existing coops, but for the future, it really will grow exponentially and we will also be autonomous, like the third market player. This is on the general level. And then I think more on the level of the people, urgency, of course, now there is a big struggle. There are a lot of protests for housing, for a better housing offer and people get very excited about comparatives because they say the state or the market cannot really provide for us. This is a way to provide for ourselves, so that’s why it’s very popular.

CC: Yeah, there’s an element of taking back control over the thing that is probably the most fundamental locus of being: the home base. On that, I mentioned before in our correspondence Friedrich Engels and his idea of the housing struggle as this subordinate struggle to a wider problem of and I think that something we’ve been tiptoeing around a little bit. This is the bed on which a lot of these discussions lies, but doesn’t get kind of recognised as much, the capitalist mode of production being something that limits these kinds of things from really flourishing, because they’re not playing by the rules of profit maximization, of accumulation and these sorts of things, also the way that cooperative development fundamentally challenges balances of power, it can be quite provocative, but they can also represent a sort of “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic” situation, I’m wondering how you feel, having been in the trenches of housing cooperative development, maybe you’re too invested in it to say anything other than a restrained response, about how it fits into wider struggles, a wider cooperative movement. You mentioned that you’re working with cooperatives outside of the industry. How do you feel about where this sits within maybe more progressive developments in society?

AV: Well, I guess housing cooperatives are a reaction to the neo-liberal housing market, with all of its problems. So in a way, it is outside the market because it’s not-for-profit. You cannot sell the house, you cannot split it, it stays in the same property regime forever. But at the same time, it’s also completely dependent on regulators. This is not a bottom-up idea to come up with housing cooperatives. Sure, there was a certain type of lobbying, but it’s also a conscious state decision to make it happen. And it really needs a lot of state or city local government push to really make the entire sector grow. So it needs to operate in this ecosystem and only time will tell if we will succeed or not. But cooperatives in general come with a very important value: autonomy. If we succeed in gaining the type of autonomy we need, then we will also be liberated from a lot of market constraints because we can set up these supportive structures that subsidise themselves. And I really see great potential and I think as soon as you tap into the cooperative movement, you really understand what type of potential there is. There’s this very interesting essay written by a friend of ours, Federico Savini, who’s a scholar at the University of Amsterdam. He has a course in urban planning where he talks about the quality of cooperatives of nesting and federating. So what these cooperatives do they replicate their structure internally and externally, and this is their way of creating a bigger structure, like a fractal. So, to make the example of De Nieuwe Meent, there are a lot of sub-projects in the project that look like De Nieuwe Meent’s governance. For example, inside the big house, there are the woongroepen, the living groups that have their own autonomy. There is a project for elderly housing inside the project. There is a project of cooperative energy that invests in the neighbourhood. There are alliances with schools nearby to make educational projects. There is a permaculture garden nearby that will do their green roof. The cooperatives are a political body that expands slowly.

CC: Like a virus… a good one. Yeah, there is an infectious quality to this sort of experience of autonomy. To my mind, I think that is probably why it’s so restrained. One of the things I wanted us to talk about was why such a common-sense idea of autonomy has not had as much register in terms of solutions to decommodified housing compared to social housing. Why is it that cooperatives have taken a bit of a backseat historically to social housing? And I have to think that there is this element of power that intercedes to prevent it. I don’t think that the ruling strata are very interested in nurturing experiments with self-governance or taking back control. It has to be something that takes its position through force, or through energy and through the force of its arguments and the efforts of the people who are committed to the ideal. Whereas social housing is a historic concession. At least in my understanding of it in Britain, social housing and the NHS are a result of the ruling class’s fear of the working class. They’re like, “Ok, we need to buy them off, but we’ll do it in this way that’s very top down. We’ll give them very minimal control of anything and slowly but surely discipline and restrain that and then sell it off in the end”. And I guess the cooperative prevents that possibility of it being sold off in the end. Coming back to this Rochdale fellow, the Maserati man, that happened because it was possible to sell off the housing.

AV: Yeah, as we said before, housing cooperatives are not on the sidelines, but they were the start of public housing in the Netherlands, they had a very important role. And as you said, I agree with you, the format was heavily regulated because of its potential and was transformed into what is now housing corporations. In the Netherlands, something very specific happened when they reintroduced the Housing cooperatives in the Housing Act of 2015. So if we compare it to other countries in Europe, Switzerland, Germany, and Denmark, there, housing cooperatives are free to grow. Usually, what happens is that there is an independent group of people. They set up their first project and then as soon as they have the financial means, they make a second cooperative and then make a third cooperative and they grow up and there are cooperatives now with two to three hundred thousand housing units in Switzerland. They are equivalent in size to housing corporations in the Netherlands, but they are autonomous. They are housing cooperatives. And the owners of the housing cooperatives are the people who live in the houses. But in the Netherlands, this is not possible because all housing cooperatives need to be independent one-off projects. So you cannot make the De Nieuwe Meent 2. You can only give your money to another independent cooperative.

CC: So there’s still some room for it, but it’s not as legally supported.

AV: This is their way of limiting the power of these organisations. There are some very interesting attempts at federating already here in the Netherlands and in Amsterdam, for example, there’s VrijCoop, this umbrella organisation that supports different cooperatives. So it’s like a network. What happens, for example, in Switzerland, is that these cooperatives grow, they share their financial means from project to project. They also have a continuity of expertise, skills and knowledge that goes from one project to the other, which is much harder in the Netherlands because of the need to be a one-off project. So we need to find other strategies. Federating is one way. Lobbying to change the law, of course. This is important. Also, the expertise of people like us can give continuity from project to project. So we see that for us the first project was very difficult and now continuing, we share our knowledge. Also, coops do it by themselves, they share their templates and their business models.

CC: This is something that reminds me of a conversation I had with Rhian Jones about her book Paint Your Town Red, which is based on this notion of community wealth building that runs parallel or is a bit of a catch-all term for various coop-type practices. The act of being real in the world has this infectious quality as well. Showing that it’s possible means that other people suddenly decide, “Ok, let’s do this ourselves”. From a personal perspective, the group I’m working with on setting up a coop development process, although it’s in its early days, was very much fuelled by this inspiring reality that it’s actually happening. It’s not coincidental that it’s the moment of De Nieuwe Meent breaking ground that gave a bit of a boost to this conversation that’s been going on between friends for a while. In itself, the fact that it exists is really great. An angle or a perspective that you have a unique or quite specific experience with is your position as an architect. and we already talked about it a bit, but maybe you could talk a bit more about the difficulties or surprises or impediments etc. (positive or negative) of working with contractors that don’t have this experience of cooperatives and also your experience of engaging with the architectural profession and the building industry and suppliers and things like that. What’s it been like being the mediator between that and this strange new concept of cooperatives (at least strange to the eyes of the people that you’re interacting with)?

AV: Well, in the Netherlands, there is the CPO, so the Collective Private Commission format that has been quite well-known for a while. That was one of the main responses to the 2008 economic crisis. While a lot of commercial projects stopped, the Zelfbouw CPOs continued. The industry makes this comparison and cooperatives for a builder or for an advisor or a structural engineer is not so different from a CPO. It’s basically a collective commission. What is a bit different from a normal project is that the stakeholders need to communicate with the client in a different way, sometimes, they’re a bit confused about who the client is. But with these kinds of experts in the building industry sector, it’s kind of ok. It’s not so strange, I think. What is more difficult is the financing side and the state or city governance side. There, it is more complicated. Because it was simply not done in this way earlier, and regulation comes to happen by doing and by experimenting. In Amsterdam, for example, there are these three projects: De Warren, which was already built last year, Bajesdorp, which has just been completed, I think the people moved in recently and De Nieuwe Meent, which will be finished next. These were the three pilots for the city of Amsterdam, where they just experimented by doing, and learn by doing. Also, the banks don’t have any packages to offer to cooperatives. They don’t know the format. With cooperatives, they don’t know how, for example, to do the so-called BIBOB scan, which is used to understand where the money comes from, if it is legal money, who the owner of these buildings is, etc. De Nieuwe Meent raised €450,000 in crowdfunding from 300 different people. How do you scan the source of this money? Also, the funding from the city of Amsterdam is very complicated and nobody had a clue before De Nieuwe Meent how to set it up. There have been many meetings of experts at all levels to set this up. More than contractors, these are the people who need to get used to it.

CC: It’s super interesting the way that a new thing comes to be, that there has to be this catching up of even the language of how you talk about it, the way that you interact and there’s such a lot to it.

AV: Yeah, and this project, I hate the word pioneers, but these first projects they’re really opening the ground for the new projects to come. Most of them are very open to sharing knowledge. There are some experts. We collaborate frequently with the financial advisor Jasper Klapwijk from Kantelingen BV, and I think he’s advising 90% of the cooperatives in Amsterdam, and he’s also advising the Gemeente in setting up their funds. Then there’s the banks, we have regular talks with Rabobank, but that is the only one in the Netherlands offering a package to housing cooperatives to housing cooperatives. So there is all this knowledge, all this ferment, it’s going to happen.

CC: So the last thing is, what are some of the basic need-to-knows for someone who’s thinking about this or in the early stages? Can you give a sense of what happens in a coop? How is it constituted? How is sovereignty developed in that kind of situation? Where is the sovereignty in the sense of like, how are decisions made in weekly meetings etc.? But also maybe you could give some information, not just for people who are thinking of getting involved, but because of our remit as speaking to the young architect, like, how does a young architect get their head around how they get involved in this?

AV: I’ll try to keep it simple, just tricks and tips. Well, it’s a great and very enjoyable process, both for citizens, coop members and also for professionals. But at the same time, it’s also a very hard process and it requires a lot of work from the volunteers. Also, as architects, as professionals, you’re going to put a lot of extra hours into what you do. So we don’t work for profit either, and it’s a process that usually takes, from the moment you have the first talk with friends until you move in, at least five years if everything goes right, so it’s also a long process, but it’s really worth it. It’s also that you’re not just building a house, so most of the people, when they get into it, think, “OK, I need a house, let’s make it ourselves”. But then, soon after, they understand that there’s much more than that. So I usually say that these cooperatives start having power from the very moment that they form. When there is a group of people that meet in a room and discuss their vision for the future, they already have such influence on the city. I think the example of De Bundel is striking, so De Bundel as a housing comparative, we started to work together a couple of years ago. They didn’t officially start the development phase yet, they have a plot, they have an optional agreement for a plot, but I think we will start to work together around the summer and they’re going to realise 130 apartments in Nieuw West. And they started with a small group of people from the neighbourhood, very interested and politically active against gentrification that is now transforming Nieuw West. They said, “Ok, we need to find a way of resisting. They founded the coop and it was immediately a catalyst for a lot of energy in the area. And because of De Bundel, a new organisation started together with other associations and they founded Nieuwe West in Verzet. So there is a lot going on even before they started the development phase. It’s not only a house, it’s much more than that. And also, it can be for everyone. You don’t need so much money for it, like usually coop members put something between €1500 to maybe €10,000 of your own money and the rest is covered with collective loans, so it can really be for everyone, but you need this time to invest and drive.

CC: That thing of it being something that has this existing, from the beginning, power to it is really, really inspiring. I find this with some of the activist work I do as well. This sense of commitment to a long-term project that might not see any returns for you at all, that it’s just good to commit to something good, or that might be beneficial to someone in the future or whatever. But also, the experience of the struggle to take some control over your life has a sort of benefit in itself. Cool. Well, I don’t know if you wanted to promote anything or talk about anything that’s going on with Time to Access.

AV: I wrote down some resources for everyone to check. There are a lot of resources already available. Some are listed on our website. And also, we give free consultations to groups. So we have a subsidising scheme where we advise cooperatives for free until they get a real opportunity for a piece of land. So it’s one of our motives to share knowledge. Also, there is a Stichting Woon in Amsterdam and Cooplink. They organise thematic courses for free for the initiation phase, so you get thematic calls about finance, what to expect from the co-design process and so on. They’re also starting to make courses elsewhere. They just started in Utrecht. Cooplink has a very resourceful website. Also, they have a podcast series about cooperative housing. There are also some interesting publications specific to the Netherlands. There is a manual from Stichting Woon called Operatie Wooncooperatie that talks about references with examples from abroad and the failed experience of a housing cooperative in Rotterdam. And a new book from TU Delft Co-Lab called Together: Towards Collaborative Living. Also, many of the cooperatives, at least in Amsterdam, are open to external members or volunteers. Also, a good way to check in is to go to their meetings, maybe work for a cooperative, for a few months, to experience the internal dynamics and see if it is for you or not.