This interview is part of our special series Besieged: Home, Land, Time, Water, which is about the spatial politics of settler colonialism in Palestine, to raise funds for mutual aid groups in Gaza. You can see the full program here. Ghost Hunting was screened in Los Angeles at 2220 Arts + Archives on August 13, 2024 in collaboration with Mezzanine to raise funds for The Sanabel Team.

Nasreen Abd Elal: I first saw Ghost Hunting in 2019, and at the time, it satisfied an urge I had to learn about my father’s and uncle’s experiences in Al-Moskobiya prison. To me, their experiences were like a black box that I couldn’t understand or visualize. The mapping and reconstruction that was at the heart of the film gave me a lot of insight into their experience, which we have a very difficult time talking about. The film feels very different after the start of the genocide and all the brutality that our prisoners are experiencing. How do you view the film now, and has your relationship to it changed since October?

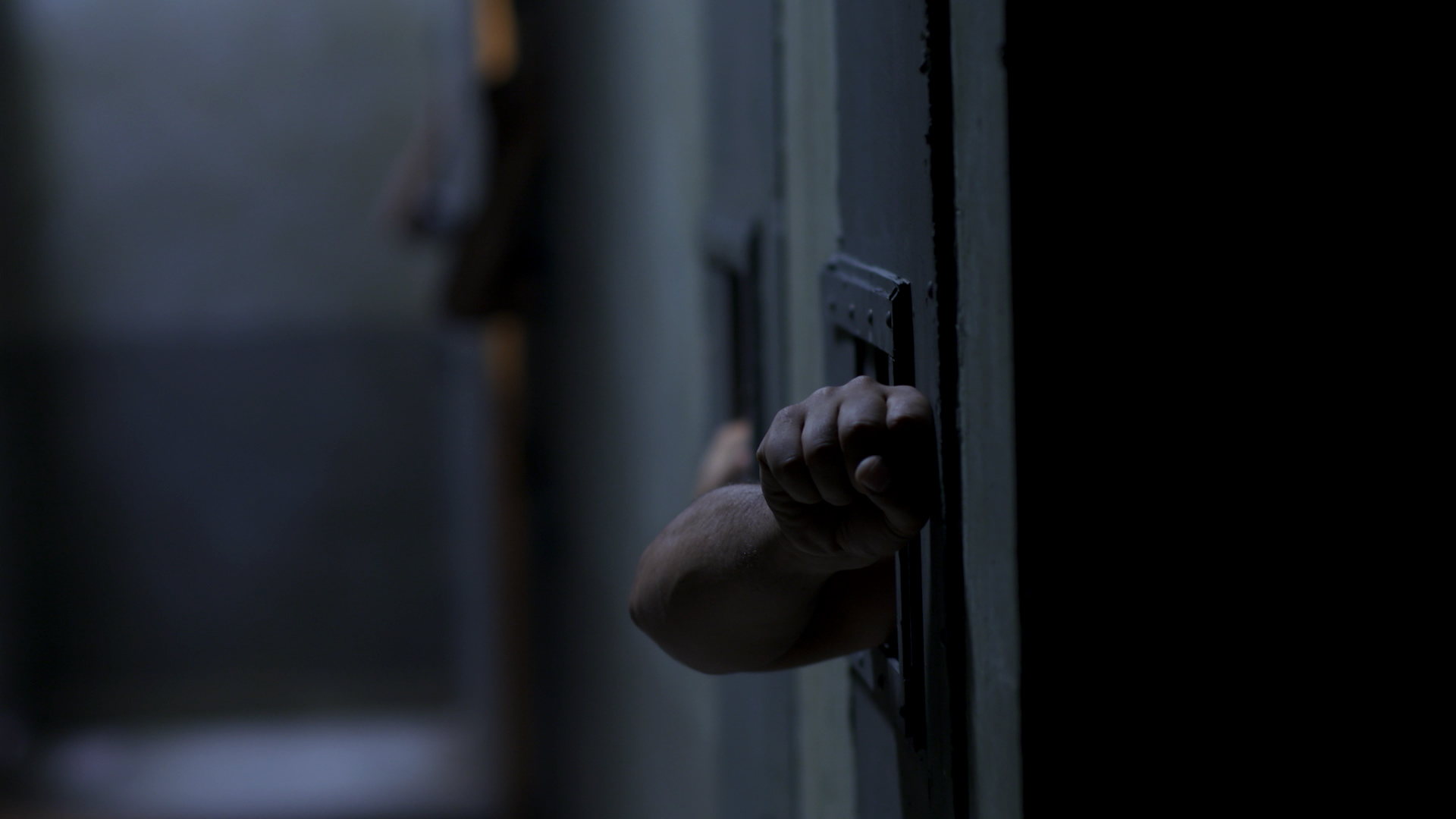

Raed Andoni: Just to start with, Ghost Hunting is not going to give you any real insight about what goes on in the interrogation centers. It’s not about the process of interrogation itself. From very early on in the film’s production, it was always more about what happens after jail. You might know that for most Palestinian prisoners, once they’re out of prison, they’re received by the community as a kind of hero. Then they have to sit in the chair of the hero and remain there for their entire lives, and it’s not easy for them to express all the horror that they’ve passed through. So rebuilding the jail is a tool to encourage them to relive and to share. It’s a tool for a deeper expression. And I think the most beautiful thing in the film is that even a Western audience can somehow feel connected to the characters. It’s because the characters are in a very human process, trying to cope with what they have.

When I’m working on a film, I want to understand something about our behavior as human beings: how we react in harsh situations, how we survive, how we manage to cope, how we can overcome. Even when Palestine gets liberated – and I’m sure it will one day – this film will still work because it’s more about us as human beings. I think this is a more interesting field for cinema. It’s not about telling or informing; it’s more about creating this mirror where human beings can see ourselves. It’s a kind of expression of our soul.

NAE: Did you start the film with this idea that it would be participatory or that you wanted to have the ex-prisoners so involved in the creation, scripting, and development of the film? Where did that idea come from and how did it develop as you began the shoot?

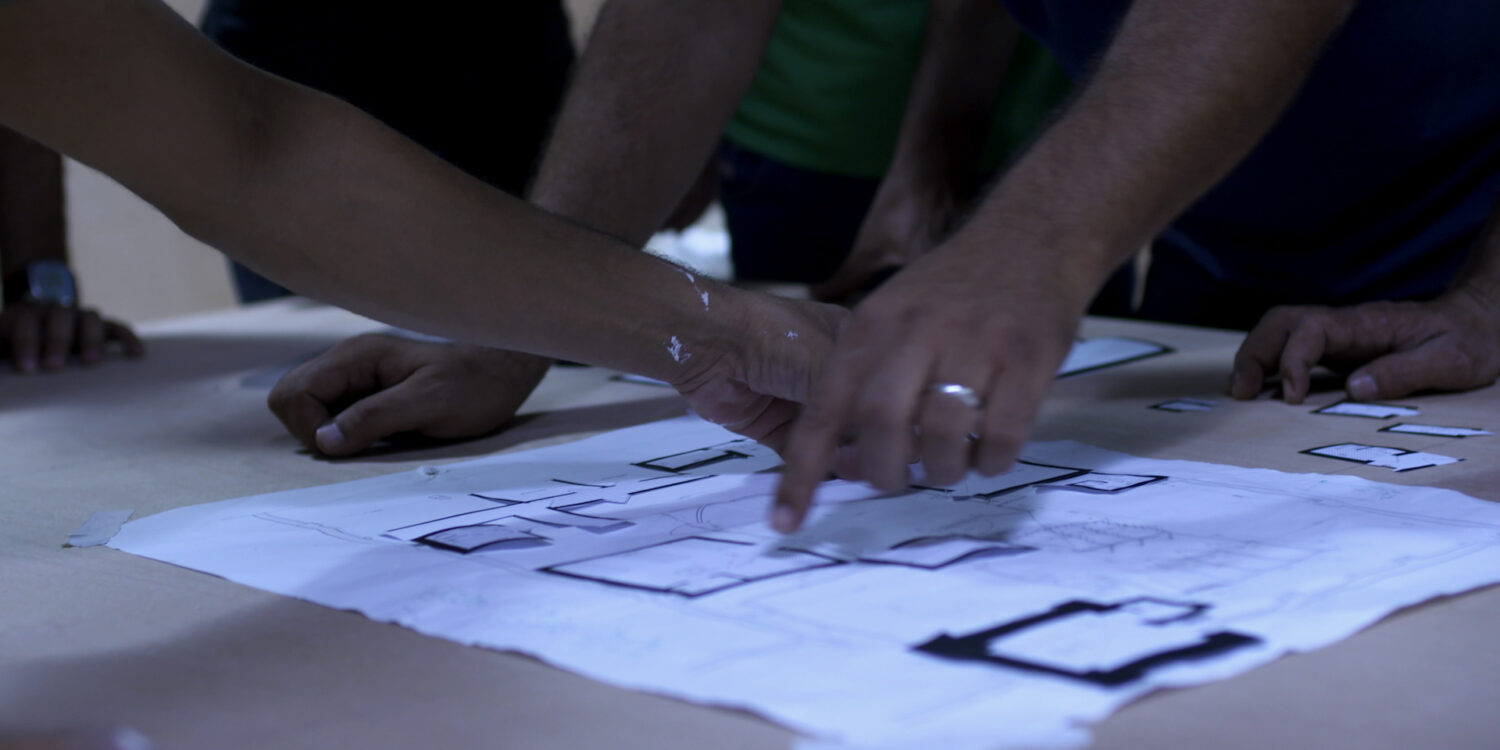

RA: I started Ghost Hunting as a fiction feature about a female prisoner in an interrogation center. During the research phase, when I met with ex-prisoners and talked to them, I always felt that there was something much deeper in the emotion that I wasn’t expressing. I started to question whether it’s necessary for it to be a fiction story. And in the beginning I thought, Okay, if I want to make any kind of film, I need to build the interrogation center. So instead of bringing in an art department, why not bring in ex-prisoners? In Palestine, twenty percent of the population has experienced such a jail, so it was very easy to find construction workers who are ex-prisoners and could build this set for me. And then I thought, Why not film this process?

I met with Mohammad “Abu Atta” Khattab, the guy whose story we ended up using for the film. In the ’80s and ’90s, he was the most popular dancer in Palestine. He’s a kind of star, and you see it in his body language. He was fascinating to me, and I thought it would be interesting to reenact part of his story and to get his reaction. Then I thought, Okay, why not ask the ex-prisoners who are building the jail to play the role of the interrogators? Palestinians love to roleplay, and I think it’s because anyone who has been under oppression subconsciously wants to practice what he passed through. So I thought, This is how the story should be told, because fiction will not save me. For filmmakers and storytellers, I think our job is to give birth to the story, not to enforce our format, our style, or our wishes. We have to help the story tell itself in an organic way.

NAE: My next question is related to what you were saying about engaging the prisoners’ issue beyond the role of sumud [steadfastness] and exploring these elements of weakness and defeat, as well as resistance and defiance. How did you do this work of midwiving the film and creating a space where the participants felt comfortable inhabiting these roles of their oppressor, of the resistant prisoner, but also of the prisoner who’s engaging with the much more difficult feelings of suffering and trauma?

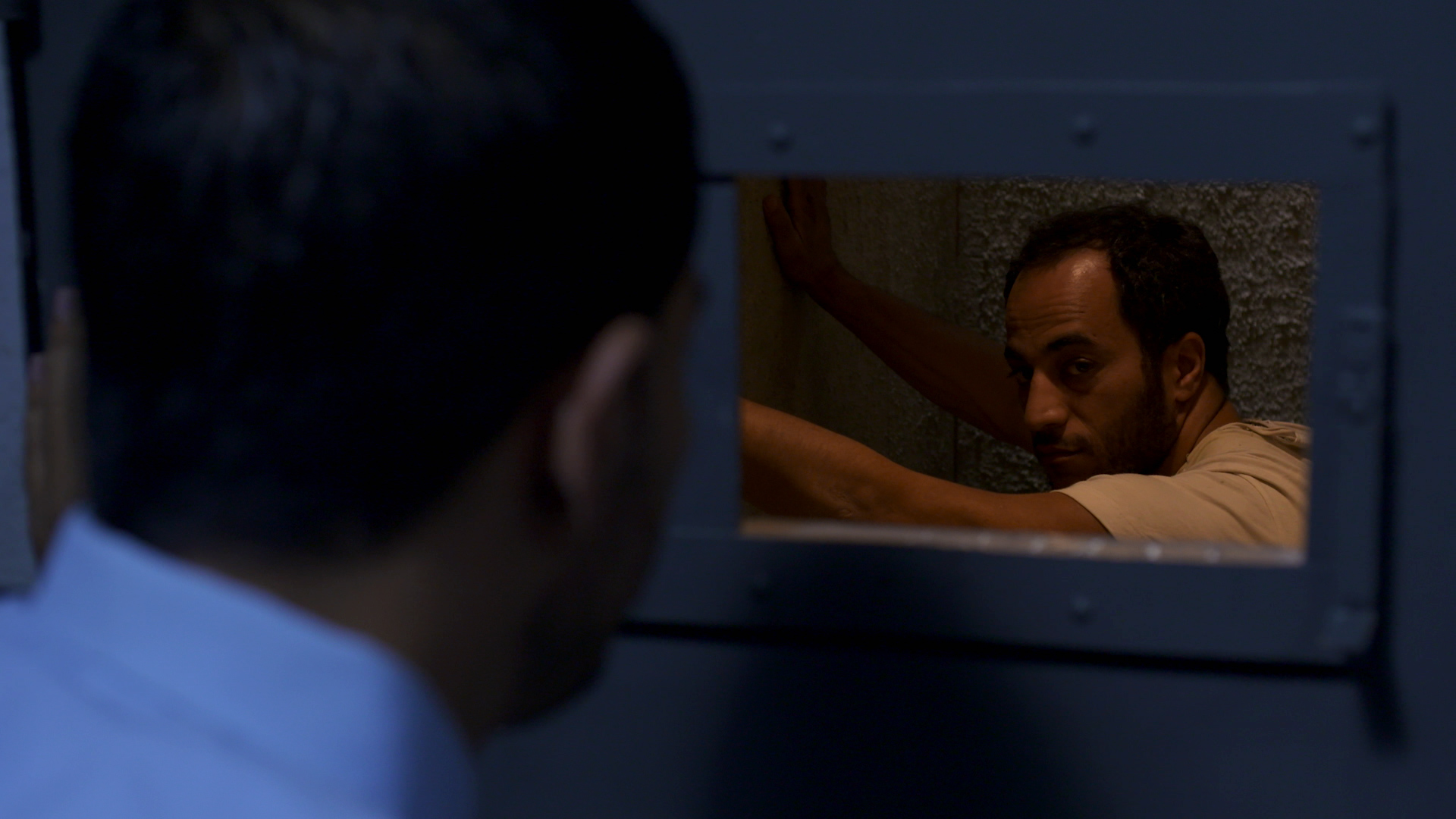

RA: When the cast first arrived on set, they didn’t know what the game was. They came as workers, and they knew that we were filming. The first scene that you see where I’m doing the casting, it’s a true scene — most of them never saw me before. For me, that was important because I wanted their relationship to the project to develop smoothly, day after day, week after week. I think they got it right away. At some point, they put me in a jail cell and told me “Now we are the directors.” They understood the film, and they were willing and happy to play the game with me and really live it as well.

RA: Before I started filming, I wrote a script for this film that was based on assumptions: What would happen if I bring in ex-prisoners and I give them characters? This one’s a metalworker, and the other one is a plumber, and so on. I gave them names, and I wrote what could happen. Of course, when I started filming, this script was not useful anymore. But it was very important for me because it gave me direction.

My job was to keep everything on track, and to give the cast the freedom to express at the same time. It was a very precise game between being a director and also a character in the film, being part of what’s happening and the one who’s controlling what’s happening, until I bring this issue of control inside the film. I think the fact that I was in Al-Moskobiya myself when I was seventeen helped a lot because, from day one, they didn’t have to explain Al-Moskobiya to me. So, from the beginning we had a different level of communication. It helped me gain their trust.

That’s why I treated myself as a character in the film. I thought, What if a filmmaker wanted to make a film about the place where he was jailed years ago? What would his behavior be? What do his ghosts tell him, these ghosts that are living inside us? Filmmakers have a lot of authority, we are like almost God on set. So suddenly I’m playing the role of God in a place where I used to be unable to breathe. For example, in the scene where you see me entering with Mohammad, where I’m covering his head and playing the interrogator: I ask him, “Where was the colonel’s office?” He points and says “Here,” and we draw it on the ground. I bring in the colonel’s desk, sit behind it, and say, “I’m the colonel now.” So from the early beginning, it was very important that I understand my psychology, not only the psychology of the participant, because I’m part of the game.

NAE: What you’re saying reminds me of Walid Daqqa’s writing on the prison as psychological warfare, and not just as a physical form of oppression. I’m curious in your trajectory as a filmmaker coming from a film like Fix Me and then doing a deeper investigation of psychology in Ghost Hunting. Where did your interest in the psychology of oppression, and the psychological elements of the occupation come from?

RA: When I came up with the idea of Fix Me, I had this interest in psychology because whenever you want to work with a character, either in fiction or in documentary, psychology is a very important element to understand. So I came up with this idea of going to a psychologist and recording my sessions. I had never been in psychoanalysis before but I decided to go and to make an entire film exploring why I’m in psychoanalysis. The first filming day was the first session, and the last day was the last session. If you watch Fix Me, you’ll see that the prison story was born inside that film.

By the way, the process for Ghost Hunting wasn’t easy. I had the psychologist from Fix Me on set with me. And it wasn’t for the cast — it was so I could discuss my method with him because I didn’t want to cause any damage. His main advice was that I couldn’t have a full contract with any of the cast, telling them when the job starts and when it ends. Anyone could quit anytime they wanted, even in the middle of the day. And that was our agreement.

NAE: Experimentation, like in what we see in Ghost Hunting, has really interesting effects, especially for the audience. I remember talking to a Palestinian friend of mine about Ghost Hunting, and she said something that really struck me, which was that she often feels frustrated by a lot of films about Palestine because they feel like they’re made for showcasing our cause to an international audience. While they might be very good at that, it’s more inaccessible to a Palestinian audience when you have to go through and explain what is Al-Moskobiya, how does interrogation work, what is administrative detention, how many Palestinians are held in prison, et cetera. It’s all of this context you have to give before you can get to anything emotionally true. And my friend said that when she watched Ghost Hunting, it felt like a film made with the Palestinian audience in mind and with Palestinians as not just the subjects of the film, but also the participants in helping to shape its narrative. What reactions and engagement have you gotten when you show this film in Palestine or to Palestinian audiences?

RA: They laugh much more than Western audiences. Western audiences are afraid to laugh, but in Palestine, they laugh a lot and it affects them emotionally a lot. One of the best reactions I got was from Mohammad Atta’s son, Atta, who actually just spent about a year in jail. Before I screened the film anywhere, I showed it in Palestine. He came and he told me “You know, Raed, it’s really strange. I never saw my father like that.” For him, seeing his father able to express and to share emotion, and to talk about the jail, it was something really impressive. I arranged the first screening for the cast, their families, and friends. And you know what that means in Palestine: it means one thousand people! We filled the biggest theater in Ramallah. Meanwhile in Berlin, I won best prize, but I had also been attacked by Variety and other Western magazines for being “ethically problematic.” I told them, “Come on, you think I’m ethically problematic in Palestine? They think that I’m too soft!” The gap is very big. In Palestine, they criticize me for not showing enough of the violence they go through.

Since the beginning of the genocide in Gaza, the film has had more screenings, and it’s been good to see how people who aren’t Palestinian are able to relate to the story. What makes me proud of this film is that ninety percent of the protagonists are working class Palestinians from villages and refugee camps. And you see how beautiful and intelligent they are. The film is not about the prison. It’s about those ex-prisoners, those beautiful men who are trying to cope through entering into this process. At one point, Mohammad told me, “When I’m here I’m so tense, and I leave the set with a lot of tension. But when I’m home, I’m always thinking about coming back to the set.”

NAE: In the credits of the film, you mention that Abdullah was re-imprisoned while the film was being completed.

RA: I think he’s in prison right now. He’s always in and out. He came to a screening in Ramallah after just being released from prison, and I was there. He was so proud. He told me, “You know, Raed, they asked me about your film. They said, you participated in a film about prisoners with Raed Andoni, and I told them no.” I told him, “Abdullah, come on! This is not some sort of secret activity, it’s a film!” And he said he would never give them any information. It’s amazing! It was very touching. I told him, “Abdullah, if they arrest me and investigate, I would tell them everything immediately!”

NAE: It’s just like the ending of the film with Ramzi saying “I had the lighter,” this refusal to engage with the guard.

RA: Exactly, and that’s a true story.

NAE: There are two other scenes that were really touching to me. The scene where Anbar is talking about Monther’s illustrations and describing the life cycle seemed to resonate with the scene at the end when Mohammad Atta’s daughter visits the prison. For the first time, you see how this experience is passed down and how the next generation is brought into it.

RA: Anbar is amazing. He’s a working class guy from Al Jalazun refugee camp who writes poetry. He came up to me and said, “You think we don’t know what you’re doing? We know exactly what you’re doing. You are searching for the jail that lives inside us.” I thought that was amazing. And about the scene when they bring their kids to the set: I wanted Mohammad to bring Lena, his daughter, to the set. But inviting the other kids was never a thought in my mind. When they first suggested it, I was in shock. They insisted on it, and they had a big discussion with the kids about it before they did it. They had reason to, because all of those kids had an unrealistic memory about their fathers in jail. So for them, seeing Adnan, for example, this beautiful guy playing with his kid in the yard, it was important but it’s also heartbreaking. It’s as if he wants to replace his kid’s imagination about this place with something that he can understand.

NAE: It seemed that it really resonated with Lena. Her reaction was, “This is spooky. It looks exactly like the cell I was in.”

RA: You see that reaction in her face. And that scene is really about the relation between the father and daughter. You see them standing in front of the cell and they’re not speaking, but you can feel it.

NAE: It seems that part of what your film is trying to explore is building a space for people to engage the trauma beyond the hero narrative, while also respecting people’s dignity and not treating them as victims but as survivors. It feels very hard to look into the future, but since the start of the genocide, it has felt that this question is only going to grow more urgent, considering the extent of the brutality and the way that our prisoners look when they come out now. I’m curious what you think of how these methodologies that you use in the film, this practice of group expression, and group healing can be repurposed.

RA: Since the beginning of the genocide and the war on Gaza, I and many Palestinians in the art scene have felt hopeless, that what we’re doing is meaningless. But seeing people engaging with Ghost Hunting made me realize how much these kinds of films can help people to see Palestinians as human while Israel is trying to dehumanize us; how suddenly you can build a relation between these beautiful guys in the refugee camps and villages and a Western audience living on the other side of the world. This will not stop the death, unfortunately, and the shocking things we see happening will not end when the war stops.

NAE: I think you’re 100% correct, and I think films like this will only become more urgent and more necessary once people exit the mode of survival and enter into trying to make sense of this genocide, which is ultimately about breaking down all sense of meaning, of our own humanity, our own understanding of ourselves and our people’s struggle.

RA: I mentioned feeling hopeless. Maybe you’ve heard of Norman Finkelstein. I met him in the late ’80s during the First Intifada when I was a teenager in Bethlehem. He was one of the first non-Israeli Jewish people I ever met, and it was shocking for me that he was Jewish but not an occupier. He was really inspiring, this guy. In ’82, when Israel invaded Lebanon, he demonstrated against the war, alone in New York for the entire eighty days. Recently I saw an interview with him where he talked about standing alone in ’82, and then during this genocide seeing all these young Americans, especially Jewish Americans, holding signs that say “Not in our name” and occupying the train station. These two pictures prove that we’re on the right side of history. It’s not about Palestine and Israel anymore: it’s about good and evil. It’s about being a human or being a monster. It’s much more clear now in the minds of millions of people, what’s going on. I’m hopeful that people will stop buying the story that God has promised some people a piece of land and so they get to claim a right over it. You can’t sell this bullshit to an eighteen year old boy who’s spending half of his day on Twitter and TikTok. Maybe it worked in the past, but I don’t think it works anymore. So that gives some hope that this unfinished injustice will reach an end, hopefully, someday soon.