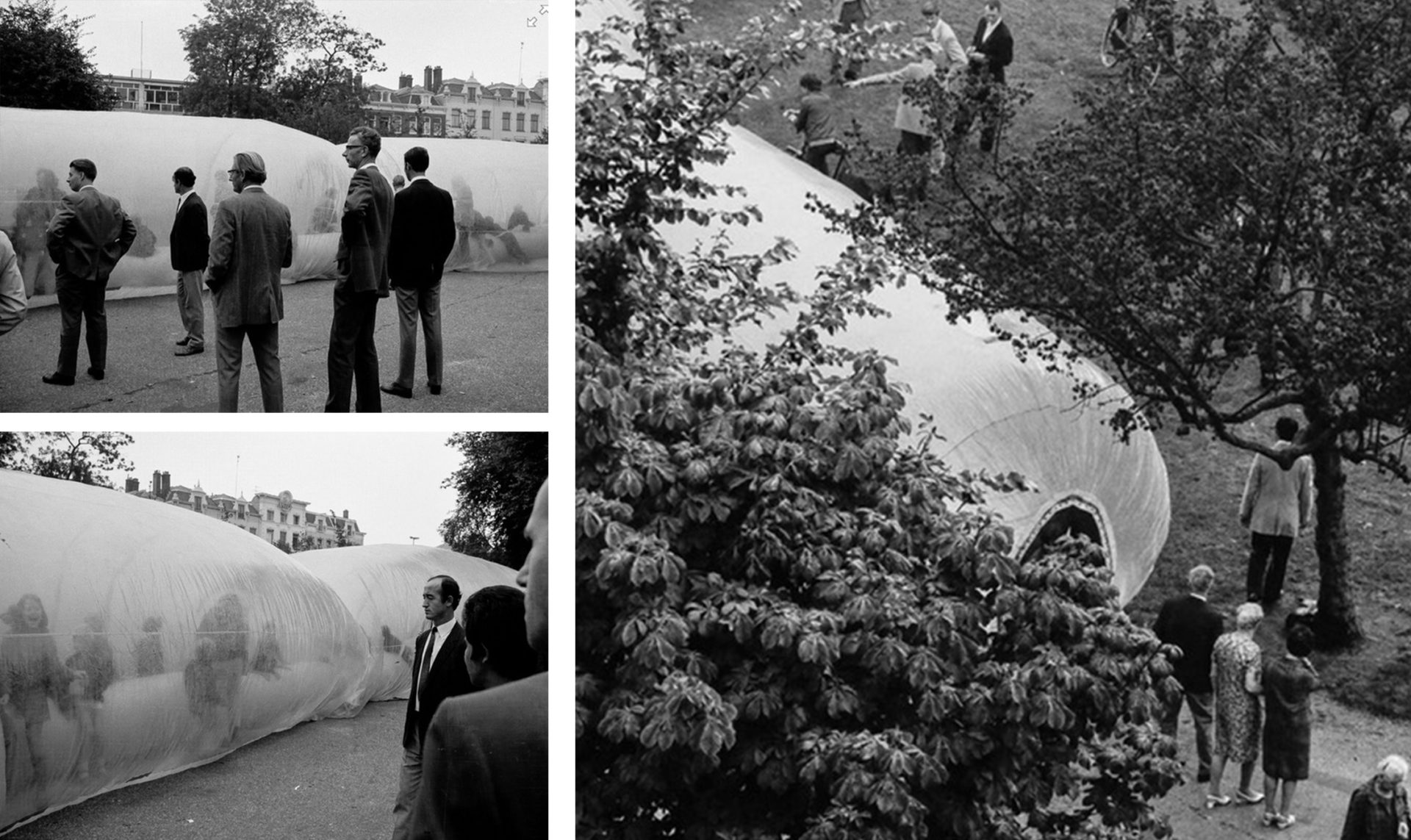

On the morning of September 17, 1969, residents of Frederiksplein in the centre of Amsterdam woke up to see an unusual spectacle on the city square in front of their houses. They witnessed the construction of a 30-metre long worm-shaped plastic object. Inside, the object seemed to host a smaller, also worm-shaped object, like a giant pillow. The residents’ children ran out of their houses in curiosity. What is this?!? One of the children soon discovered the entrance to the enormous object, with a little sign that read: Pneutube. Please enter. Curious but wary, the child entered the tube. There was not much to do inside, but it was fun to run around in there. It felt as if she was inside a cocoon. Soon enough she started jumping on the smaller worm-shaped object, making funny faces at the other curious children that were still outside the tube. Within minutes, more and more children entered the tube, all running and jumping around. They invited their parents to come in and play but they refused, suspiciously wondering: what is this?

From a distance, three young men were observing the proceedings. They were the Australian Jeffrey Shaw, the Dutch Theo Botschuijver, and the American Sean Wellesley-Miller, all founding partners of the art collective Eventstructure Research Group (ERG). The group had been granted permission by the Amsterdam municipal government to install the giant Pneutube on the square, in addition to six similar objects at other locations throughout the city, mostly inflatable tubes of various lengths and materials. Besides public squares, the objects were also installed on lakes, on the city’s canals, and in the public transport system. ERG called these objects “happenings”.

For ERG, these happenings were purely experimental. The inflatable tubes were simple enough to design, materialise and install. The tubes were industrially manufactured from large rolls of polythene, with which the group used to create immediate, dynamic, interactive event structures. The Pneutube was one of the largest objects they created, using this customised welded PVC sheeting to make a structure wide enough for people to go inside.

Constructing situations

The ERG was inspired by the work of the Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys (more widely known simply as Constant) alongside the broader group of avant-garde artists, intellectuals, political theorists, and architects called the Situationists, active in Europe between 1957 and 1972. In the late 1950s, the Situationists developed a programme for radically transforming not only the art world, but all of contemporary everyday life. Art, according to the Situationists, had become no more than commodity fetishism, so they focused their efforts on the physical city as related to by its inhabitants: the street and the building.

In 1957, Guy Debord, the French Marxist theorist founded the Situationists with a manifesto explaining the group’s principles, the “Report on the Construction of Situations” stating: “The life of a person is a succession of fortuitous situations, and even if none of them is exactly the same as another, the immense majority of them are so undifferentiated and so dull that they give a perfect impression of similitude. The corollary of this state of things is that the rare intensely engaging situations found in life strictly confine and limit this life. We must try to construct situations, that is to say, collective ambiances, ensembles of impressions determining the quality of a moment, constructing a milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behaviour.”

The Situationists then attempted to construct dynamic works with impermanent and metamorphosing forms in which “all boundaries between public and private, work and leisure must be removed,” as Jan Bryant explained in her Drain Magazine article “Play and Transformation“. The notion of play was a key element in their approach toward achieving this goal. Play should flow spontaneously from the desires of each individual, so that finally there would be no sense of boredom, and no distinction between moments of play and non-play (work). Rather, play and everyday life would move naturally from one to the other in such a way that their separateness would finally disappear in a rich and poetic stream – in other words, play and work would become one.

Underlying this concept was a resolutely Marxist political ideology. The Situationists mocked the city’s serious intent by refusing the domination of activities revolving around commodities. They wished to liberate working spaces by converting them into spaces for play and, in the service of pleasure and play, these new spaces would encourage resistance to other places of work. Behind this seeming playfulness, the Situationists had a genuinely “ambitious desire to actually change the world, to disentangle a world trapped by its obsession with capital and consumerism.” This meant “radically remaking the world in the image of the poet rather than the industrialist,” as Debord described it. The architectural type according to which their ideas were ultimately shaped was the labyrinth. The labyrinth encourages spatial disorientation and confusion with its complexity, and thus opposes the kind of openness and transparency advocated by early modernists such as Le Corbusier. In the labyrinth, each space, each passageway, each thoroughfare, is directed as much toward chance and surprise as it is toward action and progress.

The Situationists had two main objectives. First, they wished to transform the experiential nature of the modern city from one of boredom to one of play. Second, they aimed to restructure modern aesthetic experience by rejecting functionalism. To them, functionalism privileged transparency over opacity, the static and “rational” separation of spaces (domestic, commercial, traffic, etc.) over forms favouring complex, dynamic relations between different functions (such as the labyrinth).

In line with the Situationists, the ERG attempted to transform the boredom of the modern city by staging a series of public actions in the city such as the Pneutube at Frederiksplein, one of their first interventions in the urban landscape. In an interview with The Guardian, published on June 8, 1970, the group even went to the extreme to compare the boredom of the city with sickness. “People are helpless in the face of existing patterns, the daily repetition of what they see and can expect to see. It amounts to an illness. Our (interventions) are attempts to break down that series, those patterns”.

This was a direct critique of functionalist modern architecture which the group considered disrespectful to “the whim of individual people”. It was architecture that “you are just living in” rather than architecture that is “your product and something that is directly in conversation with you”. What the ERG proposed through their simple, straightforward actions, was an architecture of constant transformation.

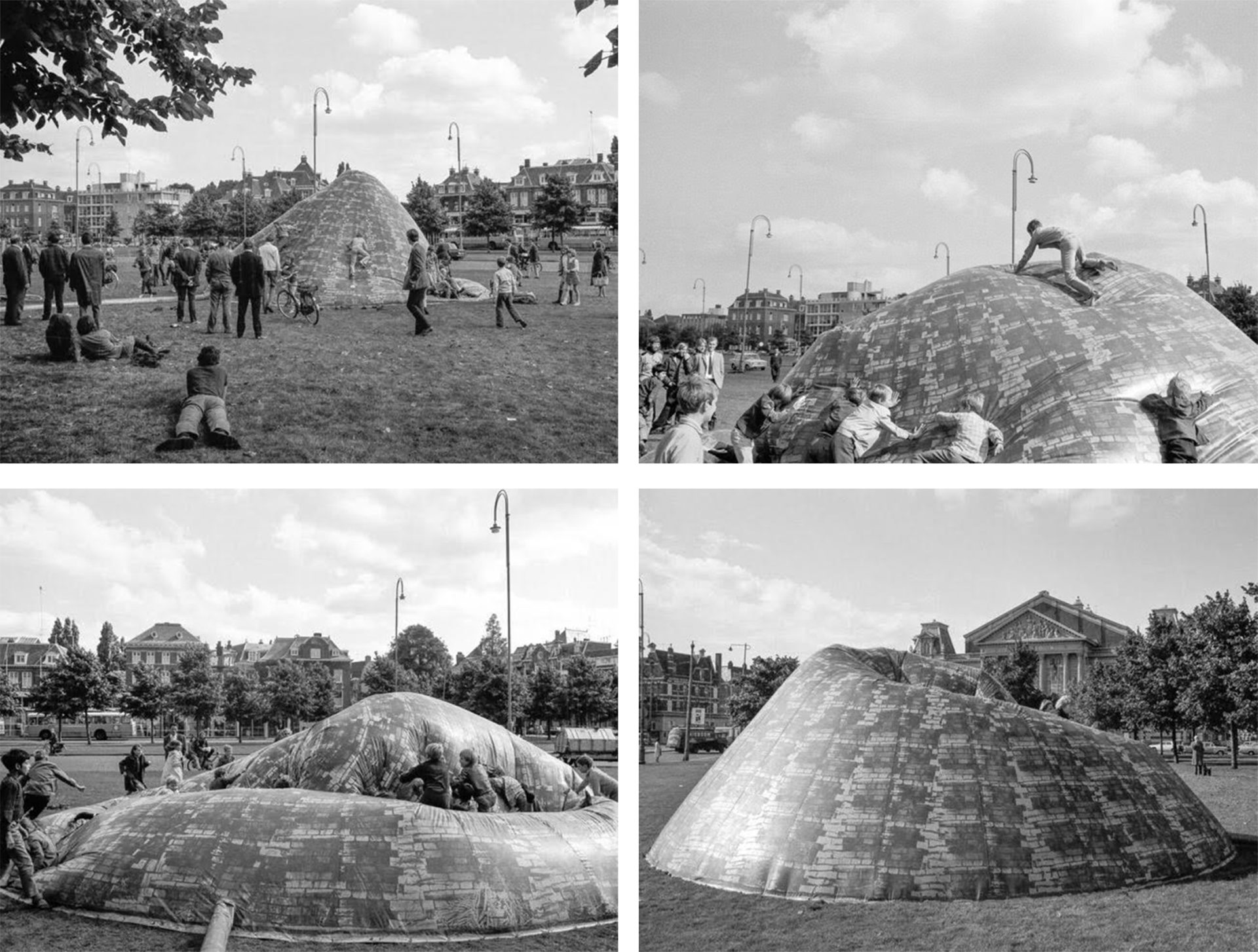

The most literal translation of this idea was their project Brickhill, which consisted of a cone-shaped air structure whose surface was silk-screen printed to make it appear as if it were made from actual bricks. This structure was shown at Amsterdam’s Museumplein. According to the group, this work took their ideas one step further, “exploding the myth of solid architecture of permanent things,” as they told Guardian journalist Stacy Waddy. It gave people, in a surreal way, the possibility of moving bricks, of moving architecture. It invested the public with the physical power to push a building around.

Leisure and entertainment, or play?

Half a century later, the same ideas developed by the Eventstructure Research Group now provide the theme for the Dutch Pavilion at the 2018 International Venice Architecture Biennale: work, body, leisure. The exhibition addresses the spatial configurations, living conditions, and notions of the human body resulting from ongoing transformations in the ethos and the conditions of labour. How will these changes affect the relationship between work, body and leisure, and which possible scenarios could we design accordingly? The main theme and the questions raised all seem derived from Constant’s thinking, and are also in line with the philosophy of the Situationists and that of the Eventstructure Research Group. An important difference, however, is that leisure seems a less powerful term than play. In contemporary usage, leisure is a passive term, associated with holidays and relaxation–a temporary break from day-to-day working life. This is merely the opposite of work, a calculated part of economic logics, while the aim of the Situationists was actually to transform work into play, in such a way that work, play and the body eventually would become one.

The Situationists considered their contemporary city of the late 1950s to be one of boredom, and wished to change it into a city of stimulation. Today, one could now argue that our own physical city is not one of boredom: 24-hour shopping, multiplex cinemas, game consoles, texting, and whatever other myriad possibilities are available to entertain us day and night – an ongoing stream of information, impulses and encouragements for active consumption. Eat now! Drink now! Exercise now! Drive now! Play now! The present-day city is one of continuous (over)stimulation. Is this the city the Situationists had in mind? Probably not. We may also ask, are all these forms of play really that effective in eliminating our boredom? Sandi Mann, author of The Upside of Downtime: Why Boredom Is Good, argues quite the opposite: “The more entertained we are the more entertainment we need in order to feel satisfied. The more we fill our world with fast-moving, high-intensity, ever-changing stimulation, the more we get used to that and the less tolerant we become of lower levels.”

The Situationists’ idea of play is quite different from the 21st century, entertainment-driven idea of play. Their idea of play strived for true spontaneity. It aimed to be active, non-conformist, anti-capitalistic and therefore critical. Today’s non-critical ‘play’ is about passive consumption, over-stimulation and intellectually apathy.

Additionally, the Situationists aimed to restructure the modern aesthetic experience by rejecting functionalism, instead favouring and celebrating complexity. Present-day cities have become exactly that: a complex of layered physical infrastructures, roads, waterways, air-routes, tubes, electricity lines, antennas, digital highways and so on. The near future will most likely see a steady-increase of the complexity of this infrastructure, with drone-like postal services, personal air transportation and more virtual landscapes added to the city. Complex infrastructure – and entertainment – is all that surrounds us. The city the Situationists imagined is there, but more than that. It has stepped up, pushed the fast-forward button and gone into overdrive.

This complex and fast-paced modern city however did not make citizens more critical towards capitalism. Today’s modern city is a largely scripted complexity of abundance, but with little place for disorder. The excess and the abundance of stimulation in the city today would make an action like Pneutube nothing more than a side note in the daily high-speed routine. People would probably shrug their shoulders, look up from their smartphones for a few moments and then continue their day. If architecture nowadays is capable at all of stimulating critical and non-conformist thinking, it can only do that through much more radical interventions. The ambitions of the ERG could be adopted, but a different output will have to be found to make an actual difference in today’s society.

What would be considered a radical architectural intervention today? Does architecture have the power to disrupt the dominant system? If this seemed possible in the past, with buildings such as the Centre Pompidou, today’s architecture seems to have lost its revolutionary potential. Not many buildings today are capable of surprising us because of the ideas that fuelled them, and not just because they are bigger, larger, or taller than their neighbours. In order to be truly radical, an architectural intervention today should be capable of criticizing the domination of technology and the authority of the algorithm. As the capitalist society that ERG was trying to dismantle does not look so different from today’s market economy in which citizens walk, travel, and even vote according to Google, Airbnb, or Facebook. Can contemporary architecture provide critical reflection on that?