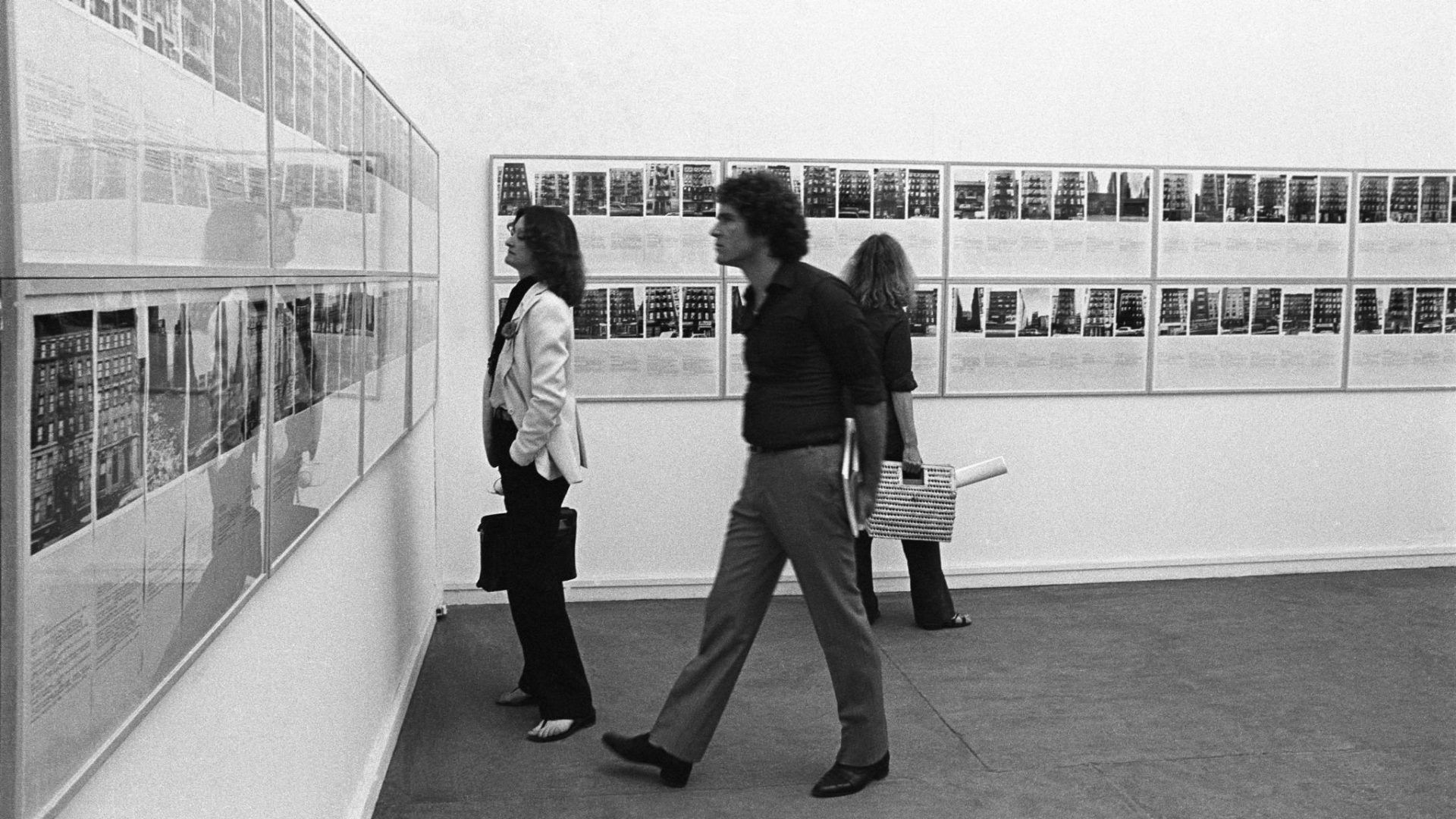

In 1971, the Guggenheim Museum abruptly cancelled Hans Haacke’s exhibition Shapolsky et al Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System as of May 1, 1971, a series of photographs which exposed the vast, shadowy network of slum housing managed by a prominent New York real estate mogul. Justifying the cancellation of the show through the museum’s charter, director Thomas Messer’s official statement proclaimed that “[the] Guggenheim Foundation is pursuing esthetic and educational objectives that are self-sufficient and without ulterior motive. On those grounds, the trustees have established policies that exclude active engagement toward social and political ends.” This was a startlingly explicit stance, indicating their sentiment that art and the museum are grounded outside of the global political issues.

On top of a hesitancy to display certain forms of political art, the political and economic histories of the institution are notably absent from museal space. The self-projected image of the museum as a politically neutral zone is reinforced by an architectural language which isolates the spectator from a broader social and political context. The ever-expanding Guggenheim global brand, which boasts an impressive roster of architects for its numerous franchises, is a clear example of this phenomenon. While the Guggenheim is an exceptional case by nature of its expansive reach, they are certainly not the sole beneficiary of museal space-making techniques which obscure the interests of capital. An inquiry which explores this concealed relationship requires a critical engagement with the legacy of exploitation embedded in the foundation of the modern museum.

How does the creation and organization of museal space help to conceal historical legacies of capital and power? And importantly, are there ethical dilemmas we must confront within our patronage and support of these spaces? Henri Lefebvre proposed that the production of space plays a key role in the dissemination of ideology. “Space,” he noted, “has its own reality in the current mode of production and society, with the same claims and in the same global process as commodities, money, and capital.” The cancellation of Haacke’s show revealed what is masked in the museum building; namely, that the museum is not an objective entity but an institution with its own social and economic interests, which exist amidst the global flow of capital.

The roots of the Guggenheim Foundation endowment lie primarily in capital amassed through global mining and resource extraction operations. In 1906, the Guggenheim family established the American Congo Company and the Intercontinental Rubber Company to capitalize on rubber and diamond extraction in the Belgian Congo. Belgium’s notorious imperial project in pursuit of rubber and ivory drew global criticism, even from other countries engaged in colonial profiteering. The Guggenheim brothers negotiated an exclusive business relationship with King Leopold II, signing a ninety-nine-year option ensuring access to rubber and “other vegetable products” in exchange for profit-splitting.

Chilean copper and nitrate mines provided another major investment opportunity. The Guggenheim family’s existing operations in Chile intensified with the establishment of Kennecott Copper in 1907, a partnership with J.P. Morgan and Company. Salvador Allende’s 1971 nationalization of Chile’s mining industry dealt a major financial blow to the company, leading to covert destabilization operations through the obstruction of Chile’s global copper export. Following Augusto Pinochet’s coup, the junta paid Kennecott sixty-five million dollars in compensation for the capital lost through the Parliament’s nationalization project. A significant degree of intimacy existed between Kennecott Copper and the Guggenheim Museum during this episode; Kennecott CEO Frank Millikin served as a museum trustee, and Peter Lawson-Johnston, a grandson of Solomon Guggenheim, served on the board of Kennecott and as president of the Guggenheim Museum.

The museum as a public cultural space is a fairly recent development, beginning in earnest as recently as the early nineteenth century when state and private entities reestablished it as a philanthropic project for the public. Increasing access did little, however, to detach these spaces from their relationship with capital and power, serving instead as an opportunity for the cultural elite to obscure the role art plays in the political sphere. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has noted that patronage is not only an effective tool for communication, but also a useful public relations tactic for the seduction of opinion.

Visible philanthropy proved to be an effective strategy to counter the growing negative press surrounding the Guggenheim family name. Established in 1937, the Guggenheim Foundation grew out of Solomon Guggenheim’s strategic art collecting, prospecting for seminal works by modern artists across Europe just as he had for ore throughout the rest of the world. These artworks reflected a progressive, technologically advanced ideology that mirrored the appearance Solomon wanted for his brand; he was desperate for the Guggenheim name to be seen in the same light as the works of artists such as Kandinsky and Klee. The inaugural museum designed by Frank Lloyd Wright further embodied the spirit of progress and set the stage architecturally for what would become the Foundation’s expansive franchising plan, continuing the brand’s imperialist history around the globe through spectacular museums in Bilbao and Abu Dhabi.

That appreciation for the latent power of modern architecture was not lost on Frank Lloyd Wright. Guggenheim and Wright shared an intimate relationship which converged upon their common high-modernist dream of technological progress, innovation, and the rejection of historical context. “Solomon Guggenheim,” Wright noted, “is the only American billionaire I ever met who died facing the future; all others died cuddling up to the past.” The intimacy between Guggenheim and Wright contrasted with the tenuous relationship between Wright and Museum Director James Sweeney. Wright and Sweeney’s ideological understanding of museum space differed drastically; Sweeney believed museums served the public as educational institutions, while both Wright and the Board regarded the space of the museum as an opportunity to please the masses and generate positive publicity for the Guggenheim name.

The public relations objective was achieved, in part, through the innovative and striking starchitecture that has come to characterize the Guggenheim global brand. Museum architecture serves as an apparatus of image-creation, a way to publicise and package values; namely, that the space of the museum is a zone of aesthetics rather than politics. The production of an ostensibly apolitical space works to obscure the relation between cultural philanthropy and the violent legacies of capital which paved the way for such endeavors.

The architectural facilitation of this objective occurs on a number of levels. The dramatic and uplifting designs which characterize the Guggenheim brand have become a standard of contemporary museum architecture. Although aspects of the architectural language may be aligned with postmodernism — having moved from Wright’s sculptural modernism to the parametrically-designed work of Gehry — key elements of postmodern architecture are notably absent. Contemporary franchises lack historical reference and pastiche, an engagement with the past which requires spectators to consider the becoming of the museum and those long-suppressed actions that precipitated it.

In some cases, the alliance between capital and museal space is quite easy to locate; the temporary Guggenheim branch in the Deutsche Bank global headquarters and Koolhaas’s Guggenheim Hermitage at the Las Vegas Venetian Casino are comically obvious examples of this tendency. The Guggenheim Bilbao, however, typifies a far more insidious model which the Foundation has employed in its expansion: the construction of buildings isolated from an existing spatial makeup, therefore allowing for the creation of independent narratives.

The Guggenheim Bilbao’s external image, like much of Gehry’s work, is complex and enticing, interpolating the guest into his exhilarating vision. The museum appears incongruous, however, a placeless alien object suddenly occupying abandoned docklands at the edge of the city. The surrounding area now typifies the same placelessness that has swept through other cities and is characteristic of global capitalism in general – a plastering over of historical space. Praise for the Bilbao Effect, retroactively termed due to the museum’s impact on the ailing city in which it is located, is sung by neoliberals around the world. The museum, and the Guggenheim brand, again, have been framed as benevolent benefactors pushing ever forward, offering a piecemeal and outsourced solution for cities struggling with the effects of deindustrialization.

Furthering the facade of institutional neutrality is an adherence to the Modernist “white cube” model, the colorless, windowless, orthogonal gallery space emblematic of the contemporary art museum. Art critic Brian O’Doherty has noted that the white cube creates a closed system of values, in which one reacts to the gallery space prior to the art. This structure prevents political and social contamination, effectively shutting the visitor out from any external contextualization of the space. Although the institutionalization of the white cube predates the Guggenheim, it nonetheless bolsters the sentiment that museal space provides a refuge and retreat from society. Wright’s prescient plan to build a ‘temple of spirit’ has proven itself to be invaluable in the efforts of museums and their benefactors to isolate the galleries from potential political and historical inflection.

The immense cultural power of the museum demands we reflect on its global consequences and contradictions, both historically and in the present. This requires architects to recognize their role in hegemonic cultural production. Architects flock to museum commissions as they provide an opportunity for widespread recognition, but the desire to produce groundbreaking work must be balanced with the knowledge that constructing the museum is not a politically neutral act.

Artists have practiced institutional critique as a means to disclose the interests informing the museum. Solomon R. Guggenheim Board of Directors, another work by Haacke, maps the corporate affiliations of Guggenheim trustees through seven framed pages of plain text. A sly vindication for the Board’s cancellation of his earlier show, the piece exposed the ways in which industry and private property inform what is presented as collective philanthropy. Locating an architectural corollary to this artistic practice may provide another avenue for institutional critique and exposure.

It is important to note that reliance on colonial exploitation is not a practice confined to the past but something that continues into the present. Tactics of architectural concealment continue to be mobilized in response. There are instances, however, in which violence breaches the museum’s progressive architectural facade. One might consider the recent scandal regarding the use of indentured labor in the construction of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi branch (also designed by Frank Gehry). A public campaign of reproach forced an institutional response to the accusations, which has resulted in multiple suspensions of the project. If such legacies can be recognized through space-making, museums can potentially build toward a different future. However, as patronage becomes increasingly lucrative and the hegemony of corporate-controlled cultural institutions continues to expand, the likelihood of any institutional transparency beyond the superficial remains unlikely.