This article is part of the FA special series Building Workers Unite

A gun kills many men before it’s done / Hundreds / Long before you shoot the gun

Men in the mines and in the steel mills / Men at machines, who died for what?

Something to buy—a watch, a shoe, a gun / A thing to make the bosses richer

But a gun claims many men before it’s done

— Stephen Sondheim, The Gun Song

Tucked away in the hills of Cupertino, above the troubled, beating heart of the Silicon Valley, there is a gash in the earth that grows larger year after year. Every day, it pours enough mercury into the atmosphere that the rain holds 6.7 times its usual weight of the known neurotoxin and pollutant. The wound spills out enough selenium into nearby creeks that the levels are 12 times over the safety standards for freshwater. Despite all this, the thing that most Californians would first associate with the Permanente Quarry, one of the most storied cement quarries in Northern California, is healthcare.

Henry Kaiser, whose legacy in California rests heavily on the almost omnipresent Kaiser Permanente health care corporation, initially made his fortune building ships for the WWII war effort. His shipyard’s success led him to form massive aluminum and steel production companies, and large government construction contracts. While the still-active health care company was created to provide for the employees of his ever-growing empire, the quarry was founded to support his construction ambitions. Since its opening in 1939, it has provided roughly 90% of the cement used in concrete for Bay Area construction projects. Like most places, the quarry has a complicated, fascinating history. Unlike most places, its history is processed, packaged, shipped and delivered directly into the sub-structure of one of the most rapidly growing, wildly disparate metropolises in the world.

Cupertino, CA

It was damp and foggy at the Kaiser Permanente Cement Plant in the early morning of October 5, 2011. The sun was still three hours away from peeking out over the Pacific to wake up the rest of the world when Shareef Allman arrived (a little late) to his 4am Wednesday safety meeting. A little coffee. Some small talk. The supervisor begins going over some things before getting started properly. Seems like the farewell party for one of the guys is going to be rescheduled. Someone chimes in, “If we ain’t gonna have no party, give me my $10 back!” Maybe a few scattered laughs. Then Shareef pulls a .40-caliber handgun out of his sweatshirt and opens fire. “You guys want to fuck with me!? You want to fuck with me!!?”

_

When architects talk about embodied energy, very rarely are they talking about bodies. But the bodies are there. Mining the ore, cutting the timber, working the machines, steering the ships. The term has come to be a cornerstone in the movement towards a more sustainable architectural practice. Choosing a material is no longer a simple matter of taste and price, there is an added criterion; an environmental cost. What is called a cradle-to-grave or life-cycle analysis (LCA) attempts to track and measure the environmental effects of a given raw material which starts from its “…extraction, continues to its production and use, and finishes at end of life when a material is disposed of…” as Edward Allen and Joseph Iano put it in their book Fundamentals of Building Construction. From this comes the concept of embodied energy, which is the sum of all energy required to extract, process, transport, and ultimately generate a given product, considered as if that energy was incorporated into or ‘embodied’ by the product itself. Often this is expressed in terms of some numerical metric, perhaps BTUs or CO2 levels. Add this data to the price of the material and presto! An environmentally sensitive picture of the cost of any given material.

But still, something is missing. Surely there is someone doing the extraction and the processing. What is this costing them? What is the human cost?

In the United States alone, about 50,000 to 60,000 workers died from occupational diseases in 2016. This was according to a recent report from the AFL-CIO, which also counted 5,190 workers killed on the job that same year. Just over 20% of those deaths happened in the construction sector. That percentage grows as you expand the lens to include mining, extraction and other points on the LCA trajectory of a material. This is to say nothing of the much greater number of workplace injuries. The mortal cost of a laborer’s task to obtain and process the material does not appear in an LCA, nor do the psychological effects of years of work in frequently grueling and monotonous conditions, nor the instances of mistreatment, malpractice, low wages and slave labor that can be found in nearly every industry, at every level of the global resource extraction process, nor the innumerable daily activities required for the workforce to reproduce itself, often carried out by women in the domestic sphere, and consequently invisible.

In the most recent iteration of the architectural turn to environmentalism, the western world has developed numerous certifications, processes, standards, and qualifications for assessing the value of a material based on an environmental standard that disregards the value of the humans producing or obtaining it. This crucial oversight has catastrophic consequences for both the planet as an entity and for all of us living on it. This is not a concept unique to the field of architecture and construction. Labor abuses in fields such as agriculture and manufacturing are frequent, rampant and global in scope. What is unique, however, is that while in many fields the use of a “Fair Trade” (or other similar certification) mark or designation is an increasingly desirable trait, in the field of architecture, labor is seemingly invisible.

Ford Island, HI

Like most days in the winter months that year the weather was beautiful. A clear blue sky with a paintbrush smattering of clouds here and there. When the first bullets ripped through the air at 7:48 am, it wasn’t clear that December 7th, 1941 would be the entry point for the United States of America into WWII. What was clear, however, was that people needed to get to cover. And fast. As the strafing Japanese fighters left pockmarks across the runway concrete, soldiers rushed to pile the sacks of bulk cement into makeshift defensive positions. Crouched behind the heap they waited anxiously. A .30 caliber machine gun poking out over the top. All that could be seen were three pairs of watchful eyes and a single word spray painted across every single bag, “PERMANENTE”.

_

In Temple Grandin’s 1980 paper on human livestock handling, The Effect of Stress on Livestock and Meat Quality Prior to and During Slaughter, she points out that if livestock animals are treated poorly, and stressed prior to being slaughtered for meat, that stress actually shows up in the food later on, altering its taste and chemical makeup. Chemically, then, the treatment of the animal beforehand becomes embedded into the meat itself, transferring into the human consumer upon eating. This study became the basis for a new wave of reform around humane livestock handling.

In the same way, the social and labor practices that generate the materials that architects consume are carried into the projects built with those materials. Is it not then possible that all of the events that occur in the creation of a product, all of its history, are embodied in the final product itself? That each kilogram of cement that leaves the Permanente Quarry also carries with it the anguish, pain and rage of Shareef Allman? The war profiteering of Henry J. Kaiser? The sweat and blood of both Japanese and American soldiers at Pearl Harbor?

The social systems that make production possible are maintained by the continued use of the given product. Each material object is proof, perpetuation and index of a history of production. And, more often than not, things produced through an exploitative system are exploitative all the way down. Exploitative extraction demands exploitative labor.

Architects, planners and other shapers of the built environment are in a unique position to devise the standards and requirements to determine how our world continues to be built. As sustainability quickly rises to the top of standards considered by building designers, it must become a more complete metric. In truth, a sustainable method of material extraction is also, by consequence an ethical (and oftentimes, equitable) method. This involves the re-assertion of the humanity that is so often lost in “green” architecture. Calculating true embodied energy, then, becomes a matter of recording the equitable treatment of both the people involved and the resources/materials used. This also requires a reframing of what we talk about when we talk about materials.

Richmond, CA

The rhythm of the work in the shipyards was almost hypnotic, both in sound and sight. Walking around Shipyard #1 it was clear to Henry J. Kaiser that his investments were paying off. Applying assembly line techniques to the building process made things go so much faster! So much so that they were even hiring women and blacks to keep everything running. Incredible. He knew that the pay was unequal, and often they were forced to deal with prejudice on the job but… it felt good to know a little progress was being made. To think the war had only just kicked off a year ago. He looked down at a female welder to supervise. The lead time on the next ship was only two weeks and the war effort was going to keep demand steady. War was booming just on the other side of the ocean, he thought. And business was most certainly booming here.

_

The claim that architectural constructions both reinforce and assert (however subtly or overtly) certain ideals and ways of living is not new. Surveying differences between poor-owned, self-built “shacks” and state-designed housing projects, bell hooks states: “Clearly, these structures inform the ways poor folk are allowed to see themselves in relationship to space… Standardized housing brought with it a sense that to be poor meant that one was powerless, unable to intervene in or transform, in any way, one’s relationship to space.” But this constructed relationship doesn’t begin with the completed building. It begins with slum clearance for a highway, with migrant labourers crammed ten to a room for a day’s work at the shipyards and, as philosopher Timothy Morton argues in his book Humankind, it begins with how we treat the inanimate objects that eventually become the building itself.

Indeed, the manner in which we treat inanimate and nonhuman things (let’s just say “things”) sets the stage for how we treat social “others”. If we think it’s morally okay to treat “things” poorly, we will think it’s okay to treat those social others we regard as “things” poorly as well. We can call this the Dehumanization Dilemma. Dehumanizing the social other justifies the continued abject treatment of any thing on the other end. This dilemma disappears, however, if non-human things are granted the same agency and privilege as humans. If we were to say that “things” have rights and agency as we do, and should be treated with respect, the argument follows to social others as well. To treat someone like dirt, to call them animals… would become an archaic thought, or perhaps even a compliment.

Unfortunately, we remain stuck in a system in which a non-human object has no value until that value is extracted, processed and converted into something of value for (typically white, male and propertied) humans. In such a system, all things — the minerals in the ground, the labour of the miner, the wood of the tree, the sweat of the logger, the gasoline in the cargo ship, the hours of the architect, the music and culture of the underclass, and the desires of the rich, etc. — become raw material to be used and exploited in various ways. But this raw material is not static, and it is not extracted without consequence. It has substance and it too can be rubbed raw and push back. Every slave revolt and workers strike, every inch the sea levels rise and every degree the global temperature increases is material fighting back. Each person and each thing holds within itself a piece of an interconnected web of production that demands our consideration and respect. The histories of our actions are embedded in the material world. And if we remain aware, it is still readable. Everything that ever happened, happens still.

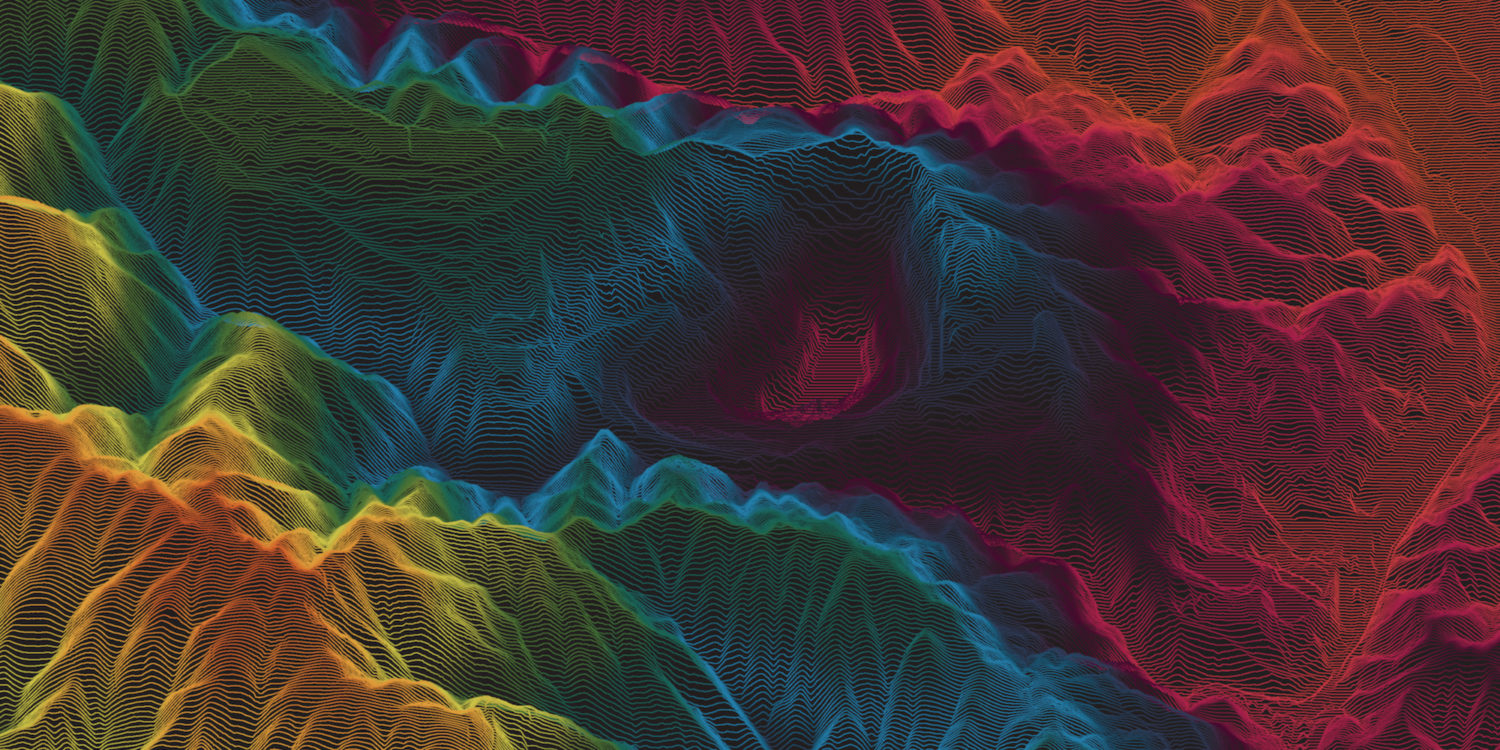

Header image: Topographical rendering of Permanante Quarry by Kevin Bernard Moultrie Daye