In contemporary Berlin, the opposite of ‘form follows function’ manifests itself in buildings created in times of horror and repression. The meaning of architectural form and style can change: a former Nazi bunker and a communist power plant show that function can follow form, and turn horror into beauty.

Bunker

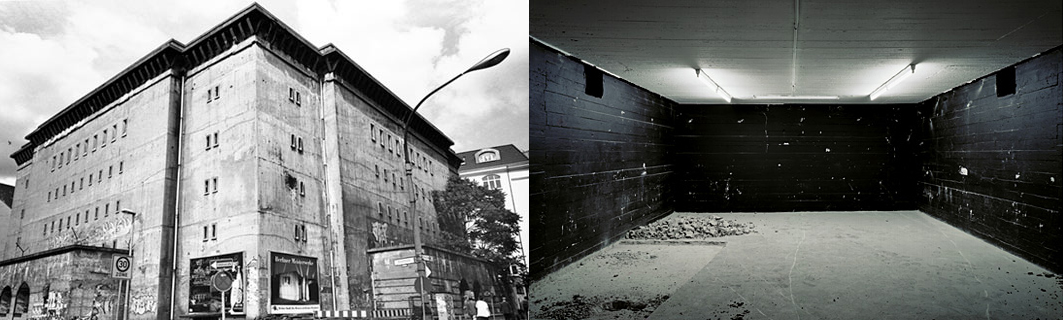

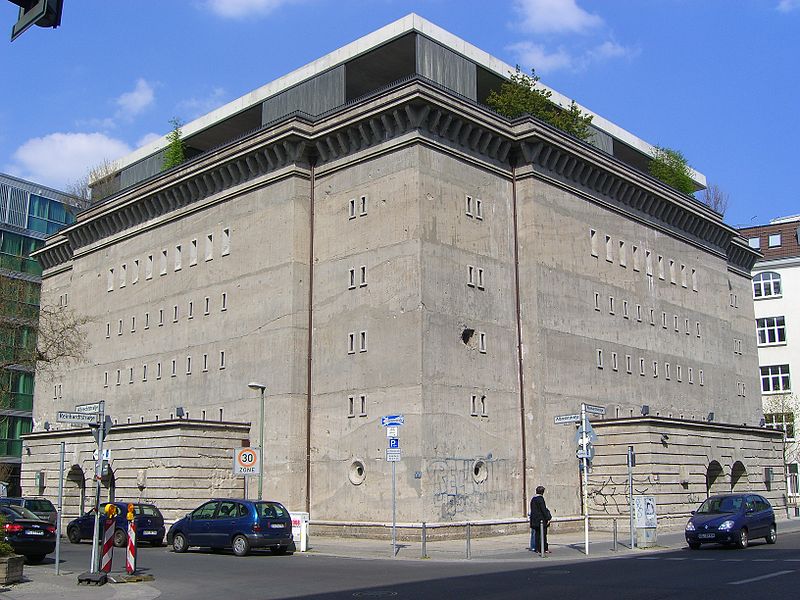

During the Second World War, under supervision of Hitler’s chief architect Albert Speer, Karl Bonatz designed a monumental building, resembling the aesthetics and proportions of a Venetian country villa. Only this building was made out of sturdy concrete walls, two metres thick, with 120 rooms distributed over five floors, which were to be used as a shelter for 2500 travellers of the ‘Reichsbahn’ during air raids. Built by the hands of forced labourers in 1943, the bunker housed the ghost of repressive times coming ever since the plan was conceived.

Prison

After the Battle of Berlin, the bunker stood firm in the apocalyptic scene of ruins and burnt down monuments, as if ‘it’ knew its time was yet to come. The bunker was seized by the Red Army, and turned into a prisoner-of-war camp controlled by the notorious Soviet secret service NKVD, the predecessor of the KGB. First meant to give shelter against the Allied bombing campaign, in the first post-war years it served as a centre for torture; a first stop for the condemned on their way to the Russian Gulag camps.

Banana Bunker

In 1961, only 700 hundred metres from the Bonatz bunker, the Berlin Wall was erected. By this time the horror era of Stalin had ended, and the communists started using the building as a cold storage for exotic fruits coming from the Republic of Cuba. Because of the extremely thick walls and a stable temperature, the building functioned well until the fall of the Wall, dubbed as the ‘Banana Bunker’.

Stalinallee

During the early 1950s, the Western Allied and Soviet sides of Berlin were preparing for the unconventional start of what would become the ‘concrete’ confrontation between two ideological opposites: capitalism and communism. The will to rebuild Berlin created a range of new visions on urbanism and architecture, which show a remarkable combination of foreign and domestic influences. In the West, under Allied control, modernism was the recipe for rebuilding Berlin, while in the East the opposite direction was dictated according to Soviet models.

Planners and architects working in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) mostly neglected the city’s burnt down monumental buildings. Instead, they worked on the rebuilding of the Frankfurter Strasse as a prototype and propaganda project for the reconstruction of an East German capital. The political agenda behind became even more evident with changing the name of this important traffic artery between Alexanderplatz and the Eastern parts of town to Stalinallee.

A competition was held for the rebuilding project, by which a ‘new way’ of rebuilding East Berlin was to be implemented. The designers were given ‘explicit instructions to follow the tenets contained in Sechzehn Grundsätze des Städtebaus (the Sixteen Principles of Urban Design)’. This prescriptive document was heavily influenced by Moscow and was commonly understood as a counter agenda to the Athens Charter. The Athens Charter, the blueprint for modernist urban planning written up by the members of CIAM, was heavily criticised in East Germany. Modernism was to be neglected as a capitalistic style infused by decadence. Liebknecht, a high positioned architect at the East German Bauakademie, declared that functionalism and the Bauhaus had nothing to do with art. Even state leader Walter Ulbricht preferred socialist realist architecture. Inspired by Soviet examples, socialist realism had a highly monumental notion in the field of architecture and planning.

Different from the later conceived and poorly built ‘Plattenbau’, the Stalinallee apartments were luxurious, complete with high ceilings, large windows, and decorations in terracotta. At the point where the Warschauer Strasse crosses the Stalinallee, East German architect Henselmann designed the Frankfurter Tor, giving the Stalinallee its iconic character.

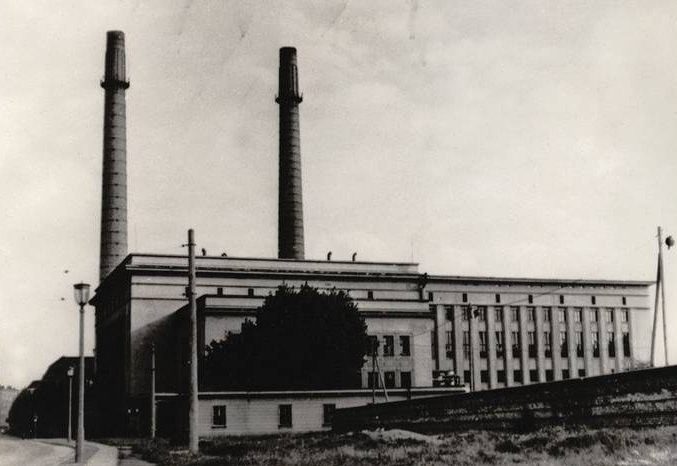

Power plant

Not far from the Frankfurter Tor and unknown to many, a power plant was erected that very much resembled the Bonatz bunker in Berlin city’s centre. The enormous power plant had a monumental composition. Especially the horizontally lined plinth made the building look extremely heavy. Above the plinth vertical windows were put in, articulated with piers that hold up the cornice, elongating the building’s volume. Small mezzanine windows, kept in a strongly horizontal articulated cornice, gave the building the appearance of a Renaissance monument. The bunker-proportioned facades reflected the ‘new’ aesthetics of socialist realism. Built in two phases, the building was made out of two ‘cubes’ of 40 x 40 metres. Oddly enough, considering the scale and monumental expression, the entrance was a small double door at the rear of the building, reflecting the non-human use of the interior. Next to this, the most monumental facade faced the railway tracks close to Ostbahnhof, overlooking an industrial wasteland. Maybe its positioning was meant as a phallus sign to West Berlin, or maybe it was a method of critical paranoia, awaiting its future use as an urban monument.

Fetish, techno and darkrooms

With the Wall falling, squatters, intellectuals and artists from the West started making use of the abundance of empty warehouses in the Eastern parts of Berlin. The Bonatz bunker was used for techno parties and soon gained a reputation for being the ‘hardest club in the world’. At the ground floor, techno music was played, while on the first floor the walls were painted black, serving as darkrooms for sadomasochistic activities.

Rumour has it that during extravagant parties such as ‘Sexperimenta’ or ‘Overture of Lust’, candles were put in each room of the bunker. When these stopped burning, it was clear the oxygen had run out and people were to leave the bunker as soon as possible. After several police raids, city authorities implemented severe restrictions and the bunker’s tenants were forced to close the building down.

However, the bunker scene brought forth a group of party organisers and DJ’s that soon moved into an abandoned warehouse close to Ostbahnhof and the former Stalinallee: Ostgut. It became known for Snax- and gay-fetish parties accompanied by heavy techno, played by DJ’s from the club’s related Ostgut Tontrager label. After years of war, separation and oppression, parts of Berlin were turning into a post-apocalyptic haven for clubbing and partying. The city’s newcomers created spaces of freedom, expression and a (gay) sexual revolution.

Temple

But then, with an increase in economic prosperity and growing real estate investments, the Ostgut warehouse was demolished to make place for O2 World, an enormous indoor venue for concerts and events. Not far from Ostgut, the club owners found a new temple to fulfill their dream of creating one of the most notorious clubbing venues in the world: the former power plant, nowadays known as Berghain. Its name is a combination of Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain, both large residential areas, split in half by the river Spree and, and more importantly, previously by the Berlin Wall. The name of the place itself embodies the unification of Berlin.

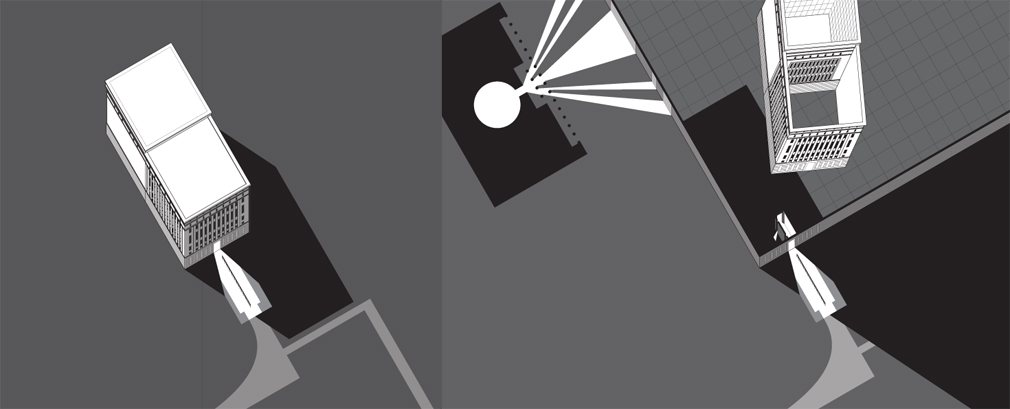

1) Berghain, axonometry. The objective, Cartesian view of Berghain, revealing only a ‘rabbit hole’

2) Berghain, agonism. More subjective, ‘virtually’ rendering the Berghain with the Berlin Wall and Schinkel’s Altes Museum, revealing the heterogeneity between monuments in Berlin.

Illustrations by the author

After entering the building through the small front door, a large space manifests itself as a wardrobe, filled with an artwork by Piotr Nathan. What follows is a large dark space with a void of 20 metres high, revealing the large turbine hall upstairs that is the club’s main dance floor. Scattered to the left and right of the turbine hall are smaller spaces, darkrooms, relaxing areas and toilets, or a combination of the three. The proportion of servant spaces (toilets, bars, dark rooms) to served spaces (the dance floors and large moving spaces) is three to two, creating a space of possibilities: welcoming on the one hand voyeurism, meeting, flirting and dancing; on the other hand intimacy, sex, and other obscurities.

From the main dance floor the Panorama Bar can be reached by a flight of stairs, a more ‘relaxed’ and heterosexually orientated space. The Panorama Bar and its servant spaces constitute a building within a building, facing two different realities: the ‘dark’ Berghain and the outside world. The windows have vertical blinds, shutting out the city beyond and simultaneously obscuring the perception of day and night while the parties continue for days and nights. Every now and then, during a musical climax, the blinds are momentarily opened, allowing daylight to penetrate inside; imprinting the image of an overly illuminated photograph on the faces of visitors.

Museum

After the Bonatz bunker had been repeatedly used as an exhibition space, Christian Boros, an art-loving advertisement entrepreneur, purchased the bunker and turned it – after years of intense redesigning – into a gallery. Small groups of people were taking tours through a building filled with art, reflecting the post-Berlin Wall artistic landscape with works from Olafur Eliasson, Wolfgang Tillmans, Florian Meisenberg and others. The building’s visitors are overwhelmed by history, not in a frozen museum atmosphere, but with time as a living concept, which visitors can interact with and relate to. The museum and its history are superimposed, creating a tangible notion of Henri Bergson’s philosophical notion of ‘durée’.

Function Follows Form

Both the Bonatz bunker and Berghain are diametrically opposed to modernism as well as the CIAM principles. With functionalism, modern architects followed the sheer function of the planned building, not aware of the fast changing times ahead. Overly lit buildings, with smooth concrete and large exposure from the inside to the outside world, seem incapable of housing more intimate experiences, especially in Berlin’s post Nazi- and communist-era. While the bunker and Berghain might have been designed to respectively function as a place for shelter and a power plant, the range of functions possible in their shells can be explained by the following.

Their facade or envelope creates a transition between inside and outside, more than the Modernist boundary between inside and outside does. The ‘honest’ façade, a credo closely related to ‘form follows function’, is absent in Nazi architecture and socialist realism. In his famous book Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas calls this the ‘symptom of lobotomy’, ‘the surgical severance of the connection between the frontal lobes and the rest of the brain to relieve some mental disorders by disconnecting thought processes from emotions’. In Western architecture the assumption regins that a ‘honest facade speaks about the activities it conceals’. Beyond a certain scale (as with monumentality) this ‘moral relationship’ between the inside and the outside is broken. Both the bunker and Berghain express a perfect ‘operation’ of architectural form because both buildings separate exterior exposure and interior use, welcoming ‘heterotopia’. According to Michel Foucault, other than utopias heterotopias are ‘real places – places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society – which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted’.

Ruin

In addition to the theories of boundaries, Albert Speer conceived the concept of ‘ruin value’, in which he argues that major buildings should be constructed in such a way that they would leave aesthetically pleasing ruins for thousands of years into the future. Over the last half century his vision became reality, although it remains unclear whether he would have approved of his buildings’ new programmes.

With new functions arriving at some point, Speer’s ‘ruins’ welcomed a new generation of hedonistic inhabitants that created spaces of freedom, expression and a (gay) sexual revolution. This group of people flourishes nowadays, and considers Speer’s and similar buildings as ‘their’ monuments. Historian and architecture critic Sigried Giedeon wrote in his ‘Nine Points on Monumentality’ that ‘the most vital monuments are those which express the feeling and thinking of this collective force – the people’, in fact defining both the bunker and Berghain as monuments without reference to Nazi or communist ideologies. Giedeon affirms this by saying that ‘periods, which exist for the moment, have been unable to create lasting monuments’.

It is in these spaces that a younger generation of Berlin people creates ‘underground’ art, music and leisure. This generation thrives on the ‘scars’ created by the Second World War and the Berlin Wall. This turns the horrors and meaning of these spaces into a true identity for present as well as future Berlin.

Perhaps the perception of all the architectural paradigms that remain in Berlin will change. Hopefully this will create support for the city’s unique heritage, as a laboratory for architectural styles and ideas, maybe the last tangible utopian place on earth. Just as Rome is a map for understanding the ancient world, Berlin can help us understand today’s power of architecture and yesterday’s architecture of power.