This article is part of the FA special series Cities after Algorithms

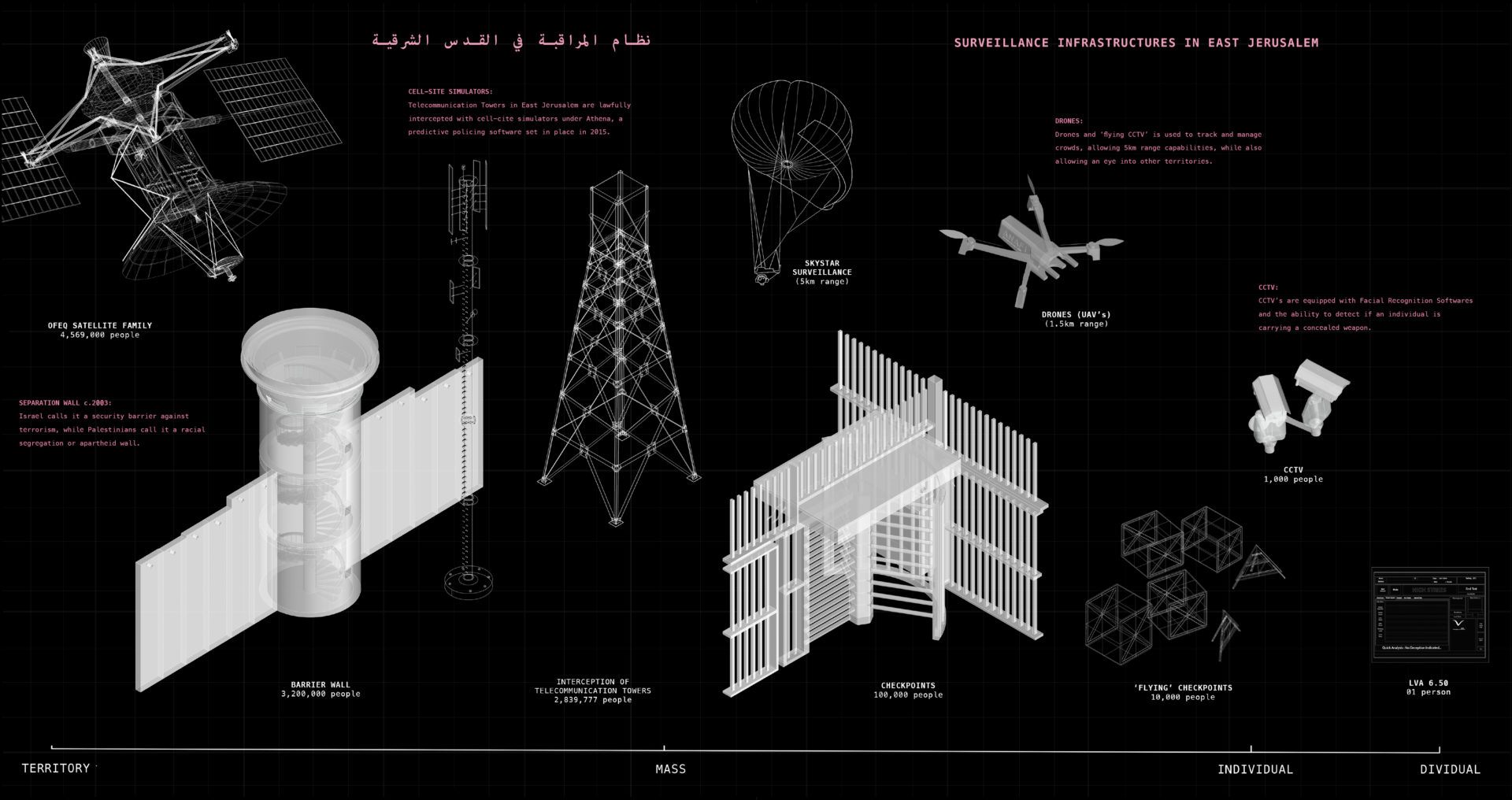

Two boundaries cut right through Jerusalem’s metropolitan region. The 1949 Armistice Line includes East Jerusalem as part of the West Bank, even though Israel unlawfully annexed thousands of hectares in and around East Jerusalem in 1967. A second boundary emerged with the erection of the separation wall in 2002, which cuts off East Jerusalem from the West Bank, placing the Palestinian population under full Israeli control. Since then, the state of Israel has instituted physical and digital infrastructures within and beyond the city to aid their political power, ensuring suppression over anything that might challenge their sovereignty. These infrastructures aim for complete and utter control at every scale, from the territory, land, and whole populations, down to individuals, their daily lives, conversations and online data.

The power imbalance in the occupation of Palestinian land can be easily observed around Jerusalem’s urban landscape. Immaculate freeways transport Israeli settlers through a landscape of dilapidated Palestinian backroads, checkpoints ensure one is never to reach work, school, or medical care on time, slower data coverage guarantees slower communication capabilities, and power cuts create constant interruptions and instability of life. Here, the Palestinians’ time is held hostage, stretching distances and isolating locations from essential resources. This is a process that queer theorist Jasbir Puar describes as sociopolitical ‘asphyxiation’. While allowing Palestinians the privilege to live, their movement is completely incapacitated, creating an entire population with mobility disabilities.

These physical control infrastructures give way for (semi-)invisible digital technologies to operate within them, from the collection and use of biometrics at checkpoints by the controversial facial recognition software AnyVision and the interception of telecommunication towers to monitor all online activity for the predictive-policing software Athena, to the centralisation of all CCTV cameras in the city to one observation centre under the Mabat 2000 initiative. With plans for a successive ‘Mabat Jerusalem’, Israel looks to expand its panoptic reach through incorporating technologies that use enhanced facial recognition and can detect concealed weapons. These plans would provide Israel with full profiles of any individual who walks through the city and its streets, making East Jerusalem one of the most surveilled places in the world.

Human and digital rights organisations such as Jewish Voice for Peace and the Palestinian NGO 7amleh have long investigated digital control and the discriminatory aspects of digital surveillance technologies across Palestine. Besides arguing against mass surveillance as a threat to Palestinian digital and personal rights, they warn of a deeper and more invasive form of control arising online, in which content in Arabic is filtered under the pretext of technical errors, hate speech and incitement. They find that every digital control system makes use of speech translation software, because of the multilingual and multidialectal society that East Jerusalem encapsulates, allowing the Hebrew-speaking state to monitor the Arabic-speaking population. However, while these speech-operated technologies have become extremely advanced in recent years, they remain deeply flawed due to the complexity of the Arabic language and its dialects, causing considerable glitches and mistranslations.

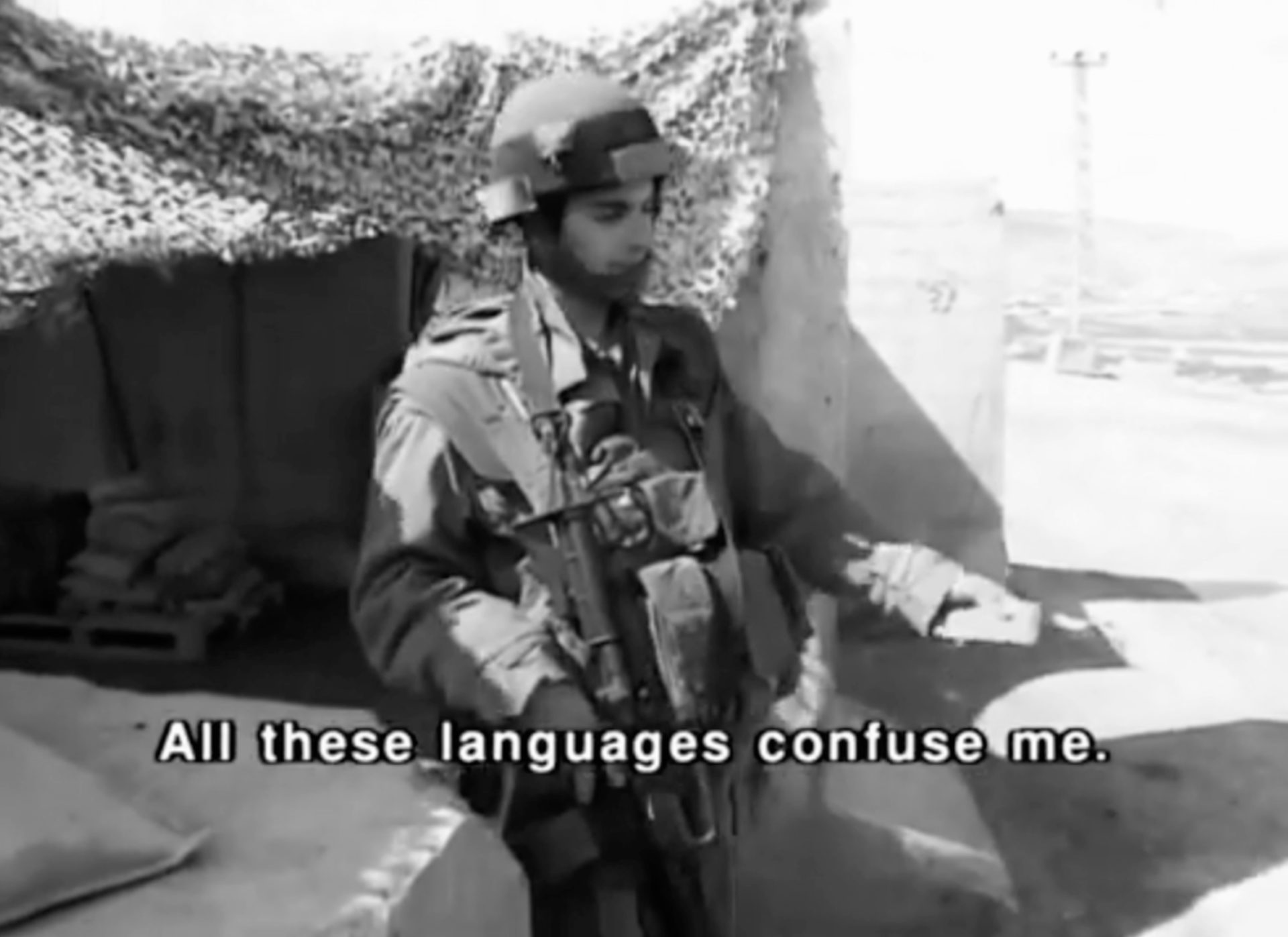

‘All these languages confuse me’ – Still of an Israeli soldier at a checkpoint while attempting to converse with two Palestinian citizens trying to cross the checkpoint. They’re seen to speak in a mixture of Arabic, English, and Hebrew in order to understand each other.

Machssomim [Checkpoint] Documentary by Yoav Shamir, 2003

In his exhibition Aural Contract: The Whole Truth, Lawrence Abu Hamdan calls attention to voice-operated technologies that aim to identify suspicious individuals, exposing the Israeli lie-detection software Layered Voice Analysis 6.50 for its built-in prejudices. LVA 6.50 is advertised for its ability to determine psychological verdicts through analysing the tensions and frequencies in your voice. It uses 8000 mathematical algorithms to compare every utterance that you speak to 129 vocal parameters. Its creators, Nemesyco, believe that all your brain activity and emotions are fully visible in your voice, regardless of the language that you speak.

As it analyses your voice and not your spoken word, the software transforms the human voice into a hostile witness, capable of testifying against the very subject from which the vocalisations came. It supposedly allows the state to determine a person’s guilt or innocence without understanding what they are saying, rendering the spoken word negligible and mere collateral.

However, through his exhibition, Abu Hamdan argues that voices are not pure articulations of sonic data that can be collected, quantified, and identified. Rather, the vocalisations that voices produce are extremely unique to each individual and are further obscured by the diversity of languages and dialects that the individual speaks. Therefore, the voice cannot and should not be separated from speech and language. Recent research has made the imperative role that language plays on the body evident. They conclude that when speaking a second language, the brain attempts to inhibit your native tongue and your instinctive emotions while activating your decision-making skills and prioritising rational over intuitive thought. By suppressing your natural expressions and personality, wouldn’t this, according to LVA 6.50, therefore be visible in your voice? In this context, the language clearly affects the outcome the software generates, potentially misclassifying innocent, non-native speakers as guilty. Deploying LVA 6.50 militarily in a multilingual context such as East Jerusalem, where the Arabic speaker must use their second or third language to communicate with interrogation officers, police, and security officials is bound to fail.

At border crossings across the West Bank, the increased usage of rudimentary and flawed speech-operated software such as LVA makes the already intrusive digital surveillance systems even more prejudiced against native Arabic speakers. These have great repercussions when placed within citizens’ daily journeys, as the software’s determination of your guilt can lead to interrogations, detainments, house arrests and imprisonments. These acts of physically disturbing innocent bodies and denying them the ability to reach their destinations, whether it be school, work, medical care, or loved ones, infringes on significant freedoms: their freedom of movement, time, and spatial liberty. Therefore, the application of speech-translation software in this context not only affects Palestinians’ digital privacy but form an additional layer to the existing infrastructures developed to control and constraint an entire population.

The digital defects of speech-operated software causing suspicion of Arabic speakers and the spatial consequences this brings for Palestinians have become a comprehensive system of control. East Jerusalemites, already victims of the occupation and strict surveillance, are forced to anxiously navigate between two consciousnesses of space, not only external to the body (the urban realm) but also internal (the oral system). In both, they have become susceptible targets. Although the Palestinian body unequivocally belongs to the city, it is treated as a glitch, an intruding irregularity. Therefore, Israel’s algorithmic intelligence enhances the existing political notion that the Arabic speaking body is but a foreign entity.

The Israeli predictive-policing software Athena is another layer of digital control, leading to among others the detainments of 15-year old Tamara Abu-Laban for texting ‘forgive me’, the arrest of Anas Abu Dabis for criticising a crime, as well as the arrests of hundreds of professors, artists, poets, and journalists. Athena constantly collects data from calls, texts, emails, and social media. It deploys algorithms to collate this information and identify individuals who may have written or said something suspicious. If Athena marks you as suspicious, Israel deems to have enough evidence for an arrest. In this case, it is irrelevant whether you have done anything questionable, as long as you have expressed something that the software weighs as problematic. In 2018 alone, Israel arrested over 350 Palestinians for the content they had posted online, especially through Facebook.

Identifying Arabic speakers, Athena completely relies on translation technologies embedded in the platforms it scans. This has led to strong criticism for the biased and discriminatory nature of its mechanisms. A prominent case happened in 2017 when a construction worker was arrested for writing ‘good morning’ on Facebook. The artificial intelligence in Facebook’s newly launched Neural Machine Translation technology allowed the software to learn, correct errors, and make its own decisions, which made it understand an innocent and informal ‘good morning’ (يصبحهم) as a spelling mistake, ultimately translating it to the violent ‘hurt them’ (לפגוע בהם) in Hebrew. This resulted in the detainment and arrest of the construction worker, showing the deep consequences of using erroneous systems for even a simple phrase.

Multidialectal languages (such as Arabic) pose a great challenge to speech recognition systems, according to research from Google Assistant’s development team. In an attempt to overcome this issue, they divided Arabic into four ‘languages’ with their subsequent dialects and sub-dialects. Yet, they still fail to grasp the entirety of Arabic’s lingual spectrum. The key challenge for Arabic machine translation is the lack of documents written in native dialects. While Google feeds its translation software with enormous amounts of Arabic documents in order for the AI to learn the language, these documents are mainly written in Modern Standardised Arabic. Palestinians however, like all other Arabs, rarely use the standardised Arabic language in informal conversations or online interactions. Instead, the flexibility of the different dialects within the Arabic language, especially in speech, means that it morphs itself depending on age, gender, social class, urban or rural context, and specific social situations. Moreover, Arabic dialects don’t only change the pronunciation of words, but further their spellings, grammar, and even replace words in their entirety.

While it can be discussed how deliberate the use of faulty digital technologies is, the results in terms of constraining the movement of Palestinian bodies in the city are the same. The constraints provoked by the repercussions of speech translation software function in coexistence with other protocols that act to contain bodies in space. In its most extreme form, the control extends into the body itself through the act of maiming. Instead of shooting to kill, Israeli soldiers are tasked with shooting at limbs, completely slowing down the body. In all these ways, the body becomes a territory to enact violent border politics. Speech-operated software is blanketed under the excuse of a necessity to uncover a hidden and threatening truth. Yet the reality lies instead in the perceived need to control the Palestinian body, both in its speech and movement. As the world has become habituated to social media, sovereignty is now, above all else, a digital question. These new frontiers suffocate those who live in political contexts characterised by direct oppression, as it no longer matters what you have done, but what the software monitoring you deems suspicious. It pushes detention centres, interrogation rooms, and prisons beyond their architectural confines, implementing them through the glitch, almost like a bullet, onto and into the body itself.

As the Arabic-speaking body navigates both the physical constraints set up throughout the city as well as the ever-increasing digital technologies of surveillance, it is imperative for East Jerusalemites to consider new forms of protocols and cultural practices that can allow them to move through their city without being indicted. The language that they speak, and the dialects in which they speak it, is a considerable part of the culture and identity that is being negated. These dialects retain a level of resolution that even the software tracing them, still can not grasp — leaving a minimal void in which some liberty can exist.

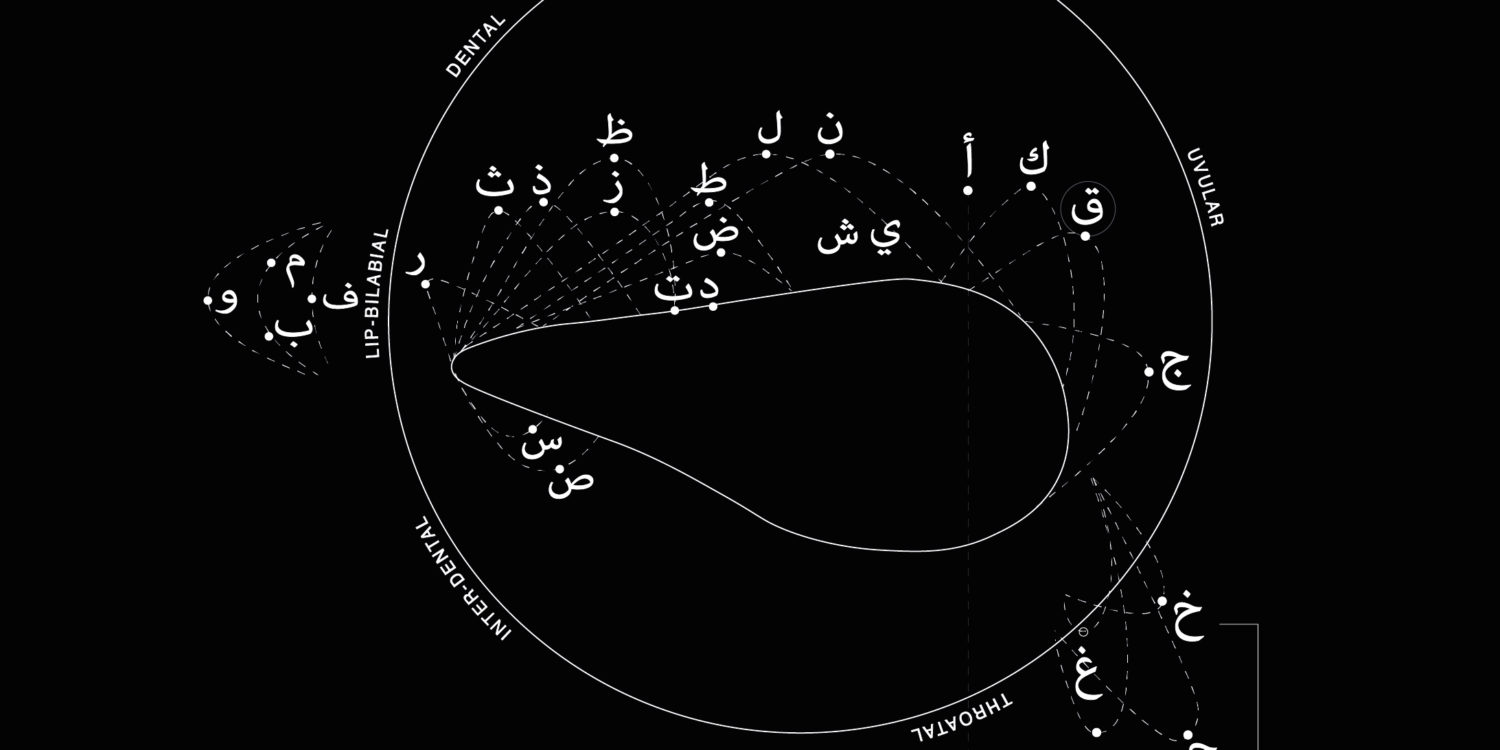

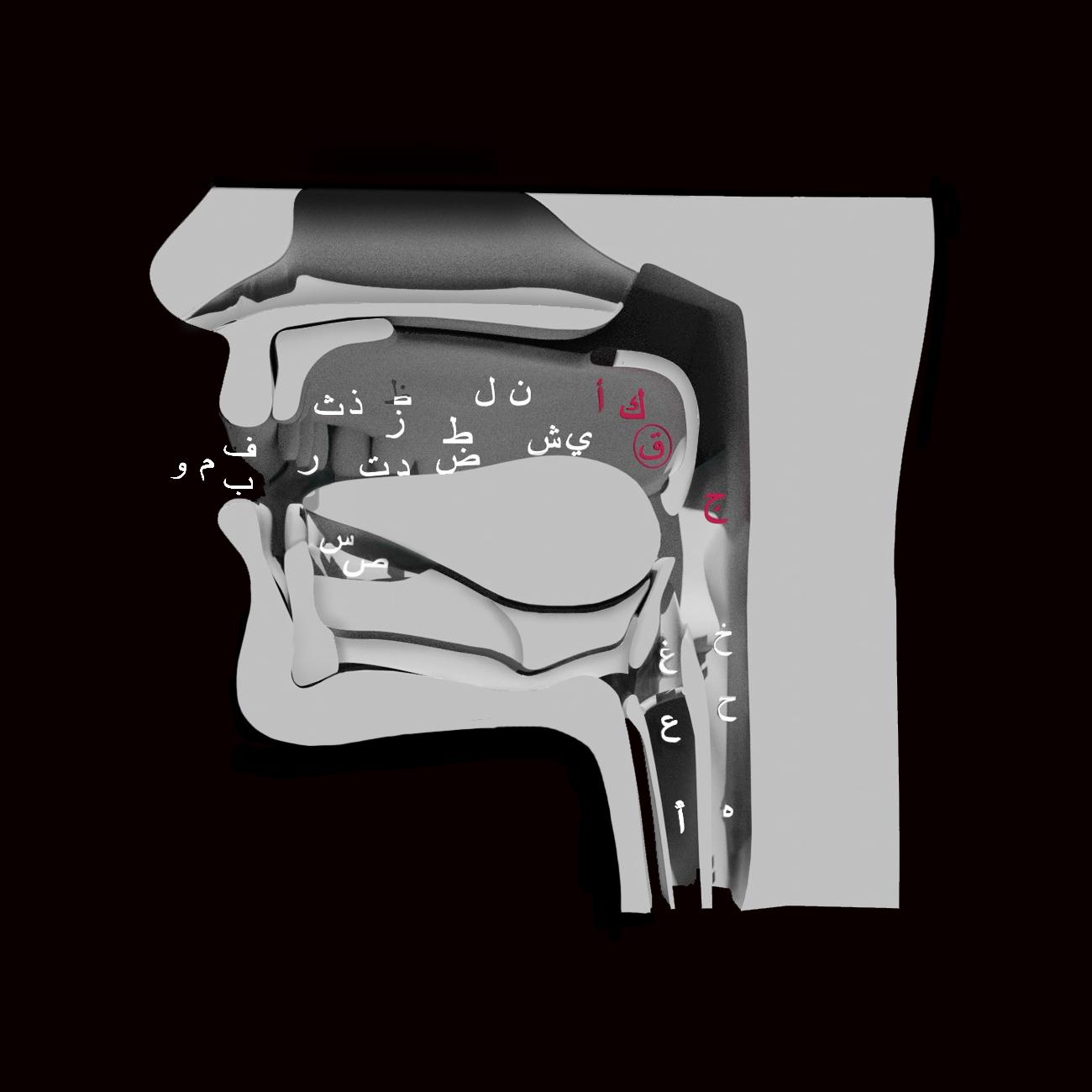

Within its current modern arrangement of similarly shaped letters, the Arabic alphabetical order can be easily analysed through computer learning as its algorithms are taught to recognise the order of patterns, strokes, and dot consistencies in the letter order. But, the internal spatial cartography of the Arabic-speaking tongue exposes a different arrangement. If we are to organise the Arabic letters in relation to their phonetical location within the mouth — starting from the depth of the throat to the tip of the tongue and the lips — we have a radically different order which subconsciously every Arabic speaker is aware of. This organisational form can also be observed at the scale of the city. As the Palestinian body is one that acts, lives, and belongs to the city and its streets, there lies an intricate cultural and historical knowledge that has been passed down through generations and retains a level of resolution far beyond the surveillance state and its artificial intelligence.

The FA special series Cities After Algorithms is produced in collaboration with the design research initiative Aesthetics of Exclusion, and supported by the Dutch Creative Industries Fund.