The long months of the pandemic have left in its path a graveyard of political infrastructures designed to make the time of the virus, if not liveable, then economically survivable. While federal and state reopening plans have often been ambiguous at best and presumptuous or heartless at worst, curiously, urban and municipal plans have for the most part escaped this characterization. Progressive cities have nevertheless insisted on reopening at all costs, painting it as a necessity for the revival of ‘vibrant urban life’. As such, large and small American cities are rolling out and expanding reopening plans, animated by the monomaniacal desire to get their “city…back up and running”; But New York City, under Mayor Bill de Blasio, has established itself as something of a vanguard—especially with the announcement that the outdoor dining program established this summer will now be year-round, and has again expanded with the addition of opportunities for outdoor storefronts on sidewalks.

As it stands, the situation is dire, with a recent comptroller report warning that up to a half of the city’s restaurants and bars that were running before the pandemic may close. At the same time, the dining industry refuses to acknowledge the writing on the wall, as it attempts to limp forward with new reopenings. Doom, in a sense, is a certainty, as de Blasio’s administration and its host of private interests seem content to furnish only a minimum of direct economic support. Instead, a curious form of business-centric individualism is becoming the order of the day: instead of explicit assistance, the role of the city is to provide a framework in which flourishing is (technically) possible. The expansion of outdoor dining is pitched as a replacement for aid for either residents or business owners, designed to “promote open space, enhance social distancing, and help them [restaurants] rebound in these difficult economic times”, de Blasio says, underlining the fact that “New Yorkers deserve more public space in our ongoing fight against COVID-19”.

The outdoor dining plan, officially designated Open Streets: Restaurants, has been greeted with great enthusiasm, with many supporters echoing the official ‘public space’ line. It’s about time “public open space” has been pressed into service “to help our struggling restaurants”, according to NYC Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer, continuing: “we need to reimagine how our public space is used going forward, including how curbside parking, our public space, is used”. Others have said the initiative is “revolutionary”, a source of “ joy and hope”, and “the way forward”. “Only a few months ago, the changes sweeping our social, economic and political spheres were considered unfathomable”, the Foster + Partners Urban Design team wrote, but now “we can harness this crisis to bring about positive change in cities”. The dead will be honored as we take back the streets, reclaiming them as ‘social space’. All these pronouncements work to obscure the fact that public space, as it appears here, is only transactional space.

There is a particular ethos of urban design which corresponds to this usage of public space as a site of consumption: tactical urbanism. This relic of the 2000s has had a new moment—a Reichstag fire-type event—and been born anew as the aesthetic wing of Open Restaurants-esque pandemic urbanism.

Predicated on an understanding of the city as a complex system that can be oriented towards positive change with small interventions of legibility, tactical urbanism above all fetishizes the ability of ‘good citizens’ to do ‘placemaking’. In that spirit, it is the charge of the tactical urbanist to create new restaurant patios for the greater good. The highest aspiration of tactical urbanism is realized in the creation of a mildly interesting backdrop for the ambulation of people and capital—which is apparently exactly what is needed right now.

But again, the economic focus is too dour for these progressives: to hear them tell it, each liberated parking space, each bike lane, and each street closure, drags us ever closer to a more equitable city. The rousing cry accompanying this pandering to economic need is that now is the time to pursue all manner of progressive-lite ‘right to the city’ projects; the self-anointed charge of the urbanist in this moment is to push back against the car, imagine the impossible, and respond to “pent-up demand”. Posing as progressive politics, what these demands really represent is an attempt by urban designers to seem relevant in a bid for work. The public/social space promised to the citizen dissolves into an atomized muck wherein the only power lies with restaurateurs putting chairs on sidewalks, surrounded by designers jockeying for their place in this new free-for-all of novelty commissions. The only citizens gaining ‘public’ space from this union are affluent urban lifestylists—that is, the ones that didn’t need it anyway.

The theoretical emphasis of public space as a marker of good design is a concrete achievement that can be traced back to the ‘New Urbanism‘ of the 90s and early 2000s. New Urbanism was espoused by the latest in a line of practitioners who situated themselves as the inheritors of Jane Jacobs and her brutally over-mythologized fight with Robert Moses. In actuality, it fused the ideas of both into a perversely nostalgic ‘neotraditional‘ developmentalism which exhumed and decontextualized past forms of urban living. Tactical urbanism was first codified by the Congress of New Urbanism, an advocacy group founded to advance the precepts of New Urbanism. Tactical urbanism builds on the neotraditionalism of New Urbanism by ostensibly democratizing it. By proclaiming the ‘death of the designer’, tactical urbanism seeks to relegate design practice to residents, who undertake a ‘guerrilla’ reshaping of their surroundings. These ‘interventions’ reject urban planning or architecture as traditionally understood, and are instead content to dwell in the crevices of the urban landscape, taking the form of tweaks rather than plans, and a scalpel rather than a hammer. The governing phrase is “pop-up to permanent”. As such, tactical urbanism appeared as a godsend to the cash-strapped progressive governments of the day by reposing urban-scale thinking as myopic and decontextualized, and identifying parklets and pavilions as the fount of community. In Janette Sadik-Khan, then Department of Transportation commissioner under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, tactical urbanism found its champion and a ratification of its ideological position when she famously invoked the ‘movement’ in her creation of pedestrian plazas on Broadway in Manhattan. But tactical urbanism above all seeks political equipoise, allowing it to whisper in the ear of powerful progressives while retaining a revolutionary character. Functionally speaking, this means that as the tactical urbanists seek greater and greater prestige, their ability to broadcast their devotion to the people, the community, the open and accessible city increases.

And make no mistake, for all the talk of community autonomy, the disgraced figure of the designer has been ushered in again through the back door, remade as a policy guru. The urban planning firm Street Plans have a design portfolio, but have also published five volumes of ‘research guides‘ on tactical urbanist strategies and best practices. Firm principals Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia, in their ur-text Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Plans for Long-Term Change, identify tactical urbanism with the idea of urban citizenship in general, providing gratuitous apocrypha extending back to 7,000 BCE. At the same time, they inch closer and closer to the levers of power, having recently collaborated with the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and their Global Designing Cities Initiative (GDCI) on the authoritative “Streets for Pandemic Response and Recovery” policy guide. And, lo and behold, the chair of NACTO is Janette Sadik-Khan, who is now also President of Bloomberg Associates, the ‘philanthropic consulting arm’ of Bloomberg Philanthropies.

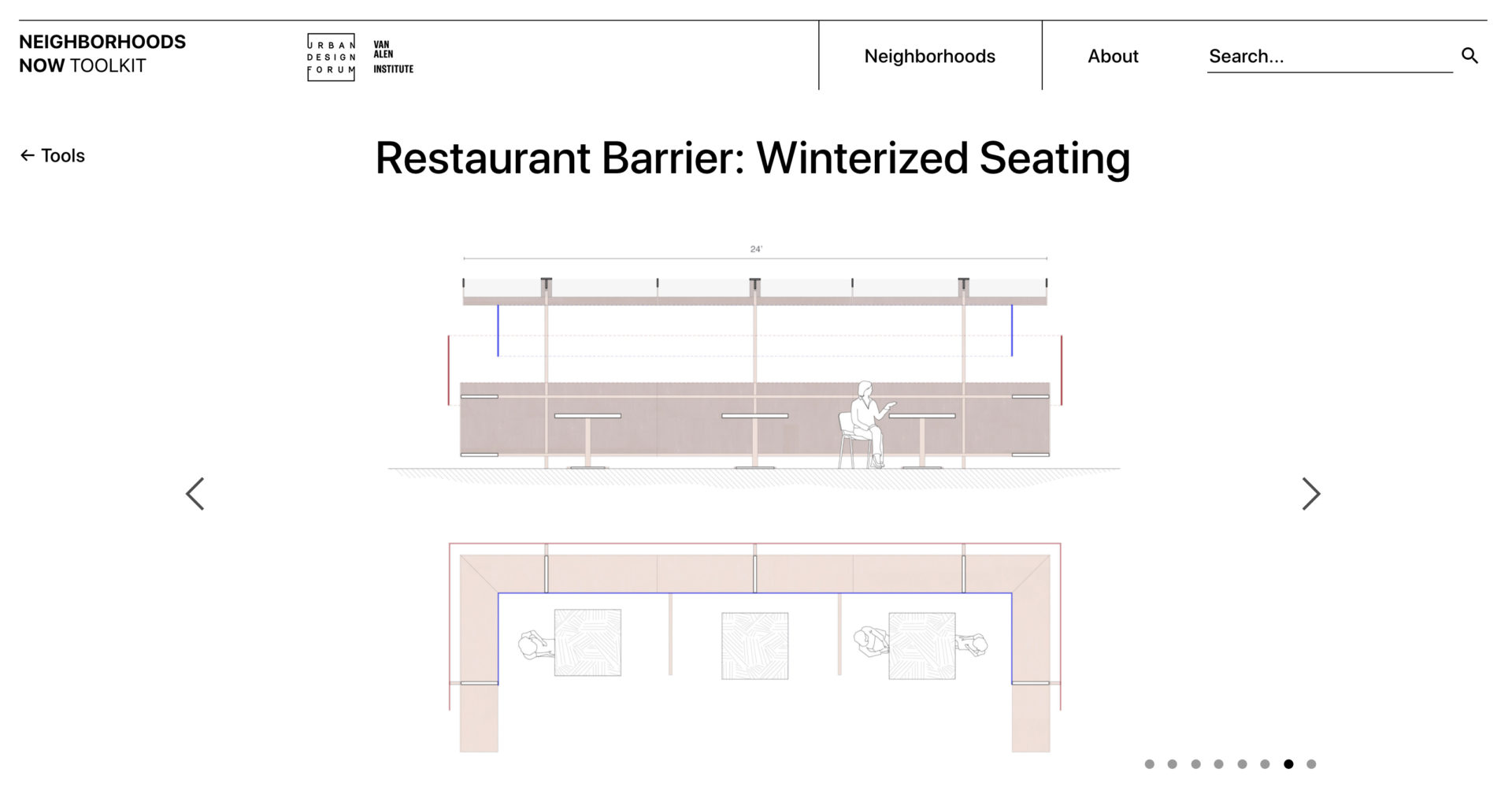

The neurotic fixation on the individual (restaurant owner, designer, Good Citizen, etc.) as an agent of change belies the fact that the tactical urbanist ‘movement’ is at this point a miasma of ideologically-aligned consultancies and partnerships which evangelize urban strategies and governance ‘insights’, build ‘coalitions’, and found ‘initiatives’. Design, when it does appear, must do so covertly, such as in the Van Alen Institute and Urban Design Forum’s Neighborhoods Now Toolkit. Here again we see the designer having ditched his demiurgic pretensions to appear as a proponent of smart policy, where any design project that does appear does so as a thrall of economic stimulus plans.

Though Neighborhoods Now adopts the usual feel-good bromides and promises to address “long-term structural inequity and racism”, this progressive masquerade does nothing more than connect designers (working pro bono) and corporations (looking to jumpstart shopping and commerce) by way of the business improvement district (or BID) and related economic advocacy groups. For example, a presentation developed by the Bed-Stuy NOW coalition, supposedly to address inequality and pandemic response in the Bed-Stuy neighborhood of Brooklyn, includes 12 architecture and design firms contributing street planter designs and outdoor dining partitions as “interventions”. The intention is clear: design is to be used to improve and develop consumptive possibilities, delivered wrapped in the language of community empowerment, diversity, and safety.

The carefully saturnalian vision of car-free promenades lined by public dining are excrescences of the Bloomberg urban ideology. While his legacy as Mayor of New York City is usually defined by his racist stop and frisk policing program or what Mason B. Williams called ‘trickle-down urbanism’, Bloomberg’s post-mayoral life has maximized his ‘philanthropic’ reach by making his vision of NYC a model for cities everywhere. The Bloomberg ideal is to run a city like a corporate firm, optimizing and innovating in order to maximize profits, platforms, and possibilities (usually by selling off and/or privatizing anything not making a profit).

In the spirit of the tactical urbanists, Bloomberg Associates, NACTO, and their legion of subsidiaries shy away from anything too explicit, instead content with the promotion of universal best practices, propagated through ‘resources’ and guidebooks which aim to introduce and make verifiable ‘best practices’ as a valid assay of urban governance. The extent of Bloomberg’s ‘philanthropy’ lies in disbursing money based on a municipality’s adherence to the tenets in these guidebooks through participation in initiatives like the Mayors Challenge (with nine awards of $1 million), What Works Cities (offering technical support and consultancy), and the American Cities Initiative (and associated grants), to name a few. Recently, Street Plans collaborated directly with Bloomberg Associates on the Asphalt Art Guide, which offers strategies for creating ‘public art’ on streets and awards the best proposals with grant money.

Despite de Blasio’s public disavowal of Bloomberg, his administration has consistently offloaded governmental functions off to private entities in a similar manner, pursuing governmental efficiency to the bitter end by jettisoning the unprofitable and unmanageable. One of de Blasio’s first major actions was to create the Office for Strategic Partnerships, intended to oversee business, philanthropic, and non-profit entities working in the city, essentially bringing them under the protective aegis of the mayor’s office itself. This cozy relationship between private interests and governance is nothing new, but that’s the point. There is a straight line connecting Bloomberg to de Blasio in their mutual promotion of capital’s power to run rampant—but where Bloomberg sought to give it a triumphal playground, de Blasio would prefer to keep it out of sight as best he can.

In the end, tactical urbanism is a valuable ideological tool, providing a readymade progressive gloss to the ongoing penetration of neoliberal strategies into urban governance and the concomitant pruning of unprofitable vestiges. The revival of urban space which it claims to herald is an example of design turned into policy, and thus debased. But it is important not to resist this process by simply calling for more power to the designers. This is a political moment in which, for a split second, the promotion of urban consumption has (for some at least) taken on a progressive appearance. Neither liberatory nor revolutionary, this has been a moment of revanchism in which designers, planners, and supposed urban advocates have yet again demonstrated their undying dedication to capital above all else.

Cover image: “Christ’s Entry into Brussels, 1889” by painter James Ensor. Walter Benjamin, writing of this painting, noted it was “perhaps first and foremost a portrayal of the horrific and chaotic renaissance in which so many have placed their hopes”.