Do you know that feeling of disappointment when you try to crush something with your hand but it’s too hard? You wouldn’t have that trouble with me. I might not be as soft as a baby’s bottom, but I’m certainly not as hard as those phones with nine lives. My whole body is airy and bubbly, a bit like Swiss cheese, but also filled all over with tiny holes. In fact, I can be up to 85% air. Isn’t that a bit freaky? It’s like when someone says to you your body is roughly 60% water, even though you can’t feel all that water for real. I am always thirsty. I’m like one of those forgotten plants, yellowing on the windowsill. If you put something water-based like plaster on my skin, I’d quickly suck the water up inside me and be completely dry again in an instant. But they always say that you shouldn’t have too much of anything in this life. I can easily get oversaturated with water if I’m left outside in the rain. Cracks form and I fall apart. But in my case, I’m pretty sure falling apart doesn’t spell death. Actually, sometimes I think death created me.

Fun fact! Did you know that Pablo Picasso had 23 names? It must be hard to live with so many names, but Picasso probably used only a few during his lifetime. I have 13 names. They are all equal because you use each one of them; some refer directly to the autoclave machine you use to create me, or to my physical advantages (I’m light and cellular), or simply to the company that produces me. Imagine that! Imagine your name referred directly to your creators. How would that work? By mixing both parent names? Or maybe you could just be named after the watery mix of chemicals you’re composed of. Technically, my names aren’t names, like cucumber’s name isn’t cucumber.

Autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) (also known as autoclaved lightweight concrete (ALC), autoclaved concrete, cellular concrete, porous concrete, Aircrete, Thermalite, Hebel Block, Starken, Gasbeton, Airbeton, Siporex, and Ytong) is a lightweight, precast, foam concrete building material suitable for producing concrete masonry unit-like blocks.

This is how Wikipedia defines me. Yes, I am the block that can resist fire for up to four hours! Let me tell you more about myself. You people know my name, but not my story, where in fact, you are the leading characters. I, on the other hand, am of secondary importance. I’m what the Greeks called the deuteragonist. I just travel through your hands. I’m a silent observer. I have felt coursing through my veins the immense energy you have devoted to getting me here: digging, cutting, shaping and transporting; all of which you wouldn’t know by looking at the new housing blocks me and my siblings create. They say that every rose has its thorn, well, I have a bunch of thorns.

To be everywhere is to be nowhere

— Seneca

Do you remember the time before you were born? No? Nor do I.

When you say “when I was still in heaven” for me it is a piece of limestone somewhere in Norway, surrounded by lakes and firs, or a stack of clay underwater somewhere in Russia. My heaven could be found in the magma of the volcano, deep under the earth’s crust. A mix of quartz sand, calcined gypsum, lime, cement, water, and aluminium powder. That’s all me. I’m not a rock, but I entered this world in a similar way: the product of several substances reacting to each other under high temperatures. Am I a wannabe rock? Or an artificial rock?

When I really think about it, I find this a bit disturbing. It’s like that feeling when you try to imagine what was there before the universe appeared. The sand forms within the magma; when it cools down, various minerals crystallise into solid rock. Quartz is one of the last minerals to form so it has a strong chemical structure. You people seem really fond of me because I can carry quite a load, so you can build a three-storey building from me alone. I think it’s the fine sand that does it.

Now, I don’t want to brag, but as I mentioned already, one of my “parents” is limestone. That makes me a distant relative to paper, glass, Portland cement, and toothpaste. Even the Great Pyramids of Giza are built mainly from limestone; the blocks were extremely big and their weight sometimes reached 16 tonnes. I remember hearing from some old limestone that shared the same quarry as the limestone in the pyramids, stories passed from generation to generation, about how they were dragged towards the construction site by 40 workers; when some of your scientists examined their bones, they found that the workers were suffering from arthritis and their lower vertebrae were impacted by the wear and tear. One of the limestones was saying to the others: What’s the point of moving us if there is so much suffering involved? We were feeling like fish in the water back there, in the lime quarry. Sadly I never met this limestone, but much hasn’t changed since Ancient Egypt; the same worry is still relevant for stones in the quarries today, but we’ll get into that more in the next part. Honestly, I consider the Pyramids closer to me than the limestones you find in decorative rock gardens, because like me they’ve been through a transformation. When I look at rock gardens, I just think that this could be me in a parallel universe if each of my parents hadn’t experienced transformation.

Limestone is a mix of minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate; the stone forms when these minerals precipitate out of water containing dissolved calcium. It’s a process of transforming a dissolved substance into an insoluble solid from a supersaturated solution. Isn’t that insane? I can’t directly relate to just one of my parents, it’s a never-ending story with endless possibilities and I am the sum. It’s like this annoying feeling when you ask someone what kind of music they listen to, and the answer is “a bit of everything”. An answer which seems to mean something but actually means nothing.

Most limestone was formed in shallow marine environments, such as continental shelves or platforms, but it can also be found in cliffs. As your miners go about extracting this part of me from the earth, the landscape changes – a meadow turns into a massive hole which has a metal fence around it; subsequently it could turn into a lake, where you swim in the summer days; in a location which used to be my bed. Some of my distant lime cousins turn into dust due to mining – the lime dust travels long distances to urban and rural residential areas. You people seem to be less keen on this part of me; it’s fine dust, and you don’t like to inhale it, you’d rather put it on your toothbrushes.

My parents have travelled great distances in my life. From deep under the earth’s crust to the top of some delivery warehouse. Through aluminium, I have a lot of relatives like paints, protective coatings, rocket fuel, and ceramics. Sometimes you put us close together, but we’re unable to have a decent conversation because of the transformations you’ve put us through. Imagine meeting a friend you haven’t met for 5 years, you’re not up on all the drama and gossip that happened in the meantime, the bond is in the past, it doesn’t go further than that.

Another of my fine parents is aluminium dust, which gives me my lightweight superpower. If I were not so light I wouldn’t be as appealing to those couples on YouTube, they wouldn’t be able to build a house by themselves. Did you know that I am linked to vaccines, therefore, to humans? Aluminium hydroxides and aluminium phosphate are commonly used as adjuvants in vaccines. Between 2000 and 2005, there was a 25% increase in the amount of aluminium infants received in their first 18 months. High levels of aluminium can result in serious health problems. Your dependence on aluminium has also been linked to a reduction of growth rate for the brain cells, plants whose growth is constrained due to aluminium toxicity in the soil.

Speed is a part of me. I think I was born with that, and nowadays as a fast player, I need a fast car, too

— Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang

Sweden, 1929: Architect and inventor Johan Axel Eriksson and professor Henrik Kreüger come up with the idea of a new kind of block that was much lighter than existing forms of concrete block. Since then I have been manufactured all over the world; you could say that I am an absolute world citizen. Now, my owners advertise me as a green material, but I have some skeletons in my closet. As you probably already know, building constitutes a significant proportion of global energy consumption and carbon emissions (some estimates calculate as high as 40% and 30%, respectively). CO2 emissions and air and water pollution are all symptoms of my production. Honestly, I don’t feel guilty, also I’m not sure if I can ever be sustainable.

The factories that produced me also generate a lot of waste, from two of the main production stages: after cutting and after the autoclaving process. In an ideal world, waste from the cutting process can be recovered and returned to the mixing tank. The residues after the autoclaving process are cracked products, which must be removed because they do not meet the technical requirements; this version of mine is harder to reuse. Technically, 25% of the leftovers, my crushed sand incarnation, could be reused in those factories, but – sorry seems to be the hardest word – the actual rate is 5%.

I am over there, there where I am not, a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent: such is the utopia of the mirror.

— Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces (1967)

When you look at your family pictures; most of the time you’re all smiling and having a great time. You don’t take photos when you quarrel. In the videos on YouTube demonstrating how I am produced, the loud, incessant sounds of machines and steam in the factory are replaced by some happy, uplifting loft music, the kind you hear in malls or elevators. In the videos, there are no humans present whatsoever. Isn’t that an epic “achievement”? (If only it were true). But I know for a fact that my parents have spent lots of time with people, including in these factories and from the moment they’re extracted from the earth.

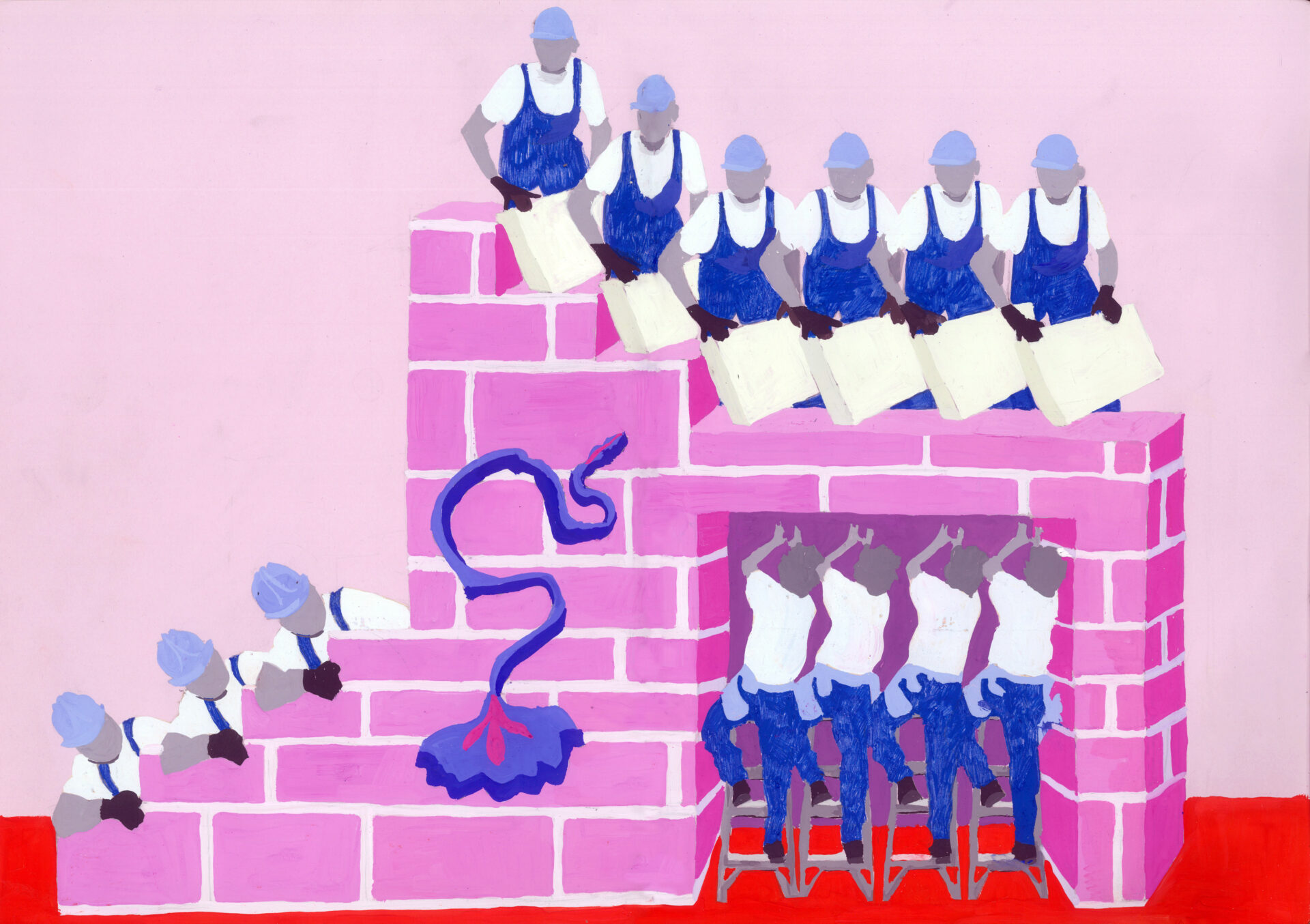

Do you ever get frustrated when someone asks you to do something impossible? For example, doing the triple-salto from the roof of a six-storey building? That’s what the people producing me are forced to do. They are my non-blood parents, who have put in turbo effort in order to bring me into being. It makes me uncomfortable when someone is sacrificing way too much for me, especially when I really don’t deserve it. According to the Australian Government’s “Labour Market Insights” webpage, clay, concrete, glass and stone machine workers (that’s as specific as the statistics get) spend around 43 hours per week at work, most of which is spent standing doing repetitive motions while being exposed to noises and sounds that are distracting and uncomfortable. It brings to mind “Around the World” by Daft Punk, imagine listening to that for eight hours – every working day is a constant loop of repetition, if you would enter the factory in the morning it wouldn’t be different from midday. This eternal circle of repetition is literally performed around the world.

“I sit in the dark. And it would be hard to figure out which is worse; the dark inside, or the darkness out”

— Joseph Brodsky, “I Sit By The Window” (1979)

When truck drivers collected my dusty parents, they took them to the factory where I came into being. Before pouring this mix into the mould, the workers layer it with oil; so they can take it out afterwards. The moulds are massive (I’ll be sliced later), so the workers need to climb inside the mould. Often they seem to be completely dominated by its vastness and the smell of the oil. While layering the mould with oil, they encounter an atmosphere akin to being trapped in a labyrinth, where the walls are four-metre-tall thujas.

My parents are mixed and cast into massive rectangular forms; after the first chemical reactions happen, I am solid but still too soft to become a part of a wall. Workers in the factory take me out of the mould with the machine, but the cleaning of the mould is done manually. My parents said they recall being in a factory somewhere in Gujarat, a region in India, where workers were bringing the leftovers in the bucket on their heads, just like you see in the pictures of coffee plantations.

“Some people want it to happen, some wish it would happen, others make it happen” Michael Jordan once said. Was he referring to the factories where I was born?

When the cast is ready, a machine cuts it up into smaller panels and blocks with tiny metal wires, thereby giving life to me and my siblings. That’s one of the bigger kicks we get out of our existence: we’re available in different sizes, but still, always the same, so we can provide the whole skeleton of a house.

After being sliced up we enter the last transformation phase in the factory, where calcite in aerated cement specimens becomes tobermorite, our main binder, which adds various outstanding properties such as superior compressive strength and thermal insulation. Humans love that I transmit heat at a slower rate than regular concrete of the same thickness. I am not afraid of fire, if I were a human I would sleep without a blanket. I spend 12 hours inside an autoclave machine, a large, vertical metal chamber where it’s extremely hot and extremely boring. Until this point, my parents were usually outside or waiting in the huge bags to be brought to the factory; but while I’m there I’m like Matilda in her terrible headmaster Trunchbull’s cupboard called The Chokey. The change of scenery is stark.

Sometimes I wonder if the 12-hour-long confinement in a metal chamber really is the key to my superpowers, or if it’s just a conspiracy to keep me down. I guess it could also be a mental preparation because endless darkness does seem to be what lies ahead of me. I’m fated to be the carcass of the structure. Just as you never see your organs, you never see me either. I am beneath the skin. You people judge whether someone is physically beautiful according to eyes, lips, hands, body, etc., but none of that could exist without the skull. Yet has anyone ever appreciated your skull (quack phrenologists notwithstanding)? I am the skull, surrounded by bricks, wallpaper, stucco and, plaster, all I see is darkness. But if you do want to find me, you needn’t travel far, because I also give material substance to all the new neighbourhoods under construction, or you can go to a warehouse. There, at least, I always see the light of day.

“My love for you is a journey, starting at forever, and ending at never”

— Inspirational quote, author unknown

Another reason why you people have a crush on us white blocks is because we’re cheaper than concrete, it’s easier for you to build a house out of us, since we’re produced in a greater range of sizes, and the construction workers can easily modify us; we can be the size of a wall if you want. This superpower opens doors for you (for those who aren’t properly connected to architecture) to build a house yourself with no extra hands and low cost. Isn’t it weird that a couple in Great Plains, Texas, surrounded by the dry-air and burning sun, can film a DIY video on how to make a house?

Alongside tons of DIY videos, there coexist videos on what to do when a white block wall starts to crack. Already when a builder moves us from point A to point B, tiny cracks appear. Not everything on every construction site is done with machines; the way workers stack the white block is not unlike martial arts. The workers and us blocks carry the same curse: just as we blocks come into this world dressed in the same fashion, their work is always the same.

“I hope you find someone who isn’t confused about how they feel about you. Someone sure, someone devoted” R.H Sin once wrote. Was he speaking about my desire to meet a human who treats me like autoclaved aerated concrete block and doesn’t confuse me for a brick? We are related, but we aren’t the same! Since bricks and concrete have been on earth longer than me; there are established standards on how to use them. Collapsing houses and cracked walls are a consequence of not treating me as I am: aerated autoclaved concrete.

“You can build anything with this stuff, use your imagination”, they say, but there’s another side to this coin. I can’t stop myself from cracking when the worker carries me around the construction site, I crush at the corners, and I am always facing the consequences. But crushing is what I crave in my life as a block. From the moment I have tiny holes or missing straight edges I am wounded, I am not a healthy block anymore. When humans aren’t healthy they start to give up unhealthy habits, something similar happens to me, I am completely disqualified from my game, my “purpose”, I don’t matter anymore.

What to do with this injured block? If you cared about the environment you would take me to a waste dump, where I could live out the rest of my life causing relatively little harm, albeit excluded from my “purpose” in endless loneliness. That episode of The Simpsons when Bart and Milhouse play hide-and-seek, and Milhouse reaches a record of 3 weeks without being found after Bart goes on holiday, it’s like that. But in my scenario, Bart never returns from his holiday. If it rains, I’ll absorb enormous amounts of water and become even more brittle and eventually turn into a powder and end up back on the earth. If it’s windy then I have a window to escape and lean next to a highway or farmland. In this abandoned shape you can find me anywhere, on the street, in a meadow, even on your roof. I can’t stop travelling. Some journeys may end where they started. You could say that I become what I am by destroying my roots.