This article is part of the FA special series Building Workers Unite

In Whites, Jews, and Us: Toward a Politics of Revolutionary Love, the French decolonial activist and writer Houria Bouteldja issues praise to only one white European man: Jean Genet. In Bouteldja’s qualification, Genet earns his laurels by virtue of his historical “betrayal” of the white race, a feat that Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus never accomplish. Genet achieves this betrayal by rejoicing at colonial France’s losses at every turn and refusing to hold his motherland in much higher regard than he does Hitler’s Germany. Genet sees in the liberation of the colonised and racial subject his own liberation, and so his rapport with Jewish, Algerian, and Black people is not one of benevolence but of shared rage. He refuses to take an interest in French political debates, insofar as those national debates do not account for migrant workers and the peoples of the former colonies. Whatever democracy the French instil in the heart of their empire does not concern him—he can only see that it is at the helm of an engine still running on the centripetal dispossession of colonised subjects.

In the early 1970s, when Jean Genet was in the United States working with the Black Panthers against the backdrop of Huey P. Newton’s trial and incarceration, Adolfo Natalini of the radical architecture group Superstudio urged designers to do without design if design is merely at the service of “inducement to consume,” “the codifying of the bourgeois models of ownership and society,” and “the formalization of present unjust social divisions.” To say that these functions are as entrenched in the profession as they have ever been would be an understatement. Yet at this historical juncture, the U.S. prison-industrial system and its enshrinement of racial capitalism are being called into question by the Black Lives Matter movement, popular revolts have been sweeping across Beirut, Santiago, Khartoum and other cities in the Global South, and we are beginning to acclimatise to life in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this landscape, it is imperative that we imagine architecture and design work that can respond to, or at least not hinder, other struggles happening in its proximity.

I will not overplay the analogy between a race and a profession. The two are not structurally homologous, even when design and architecture fields are still overwhelmingly white (in the US, 91% of architects registered with the American Institute of Architects are non-Hispanic whites). Broadly speaking, designers perceive their profession as middle-class and white-collar, requiring a high level of expertise acquired through several years of education and practice, even when the vast majority of design and design-adjacent workers live in great precarity. These identifications inform the political subjectivity of the professional designer class, manifesting in how designers and architects associate, and in the opinions they hold about technical expertise and the social distribution of power. In the face of today’s exigencies, a political betrayal of and a disidentification from these professional values is in order.

Aerial rendering of June Jordan and Buckminster Fuller’s Skyrise for Harlem proposal, published in 1965 in Esquire magazine. Jordan is not credited by Fuller in the illustration. For more information about the proposal and June Jordan’s under-recognised architectural career, see Representing the “Architextural” Musings of June Jordan by Charles Davis II.

The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller.

Identification takes place alongside association. A designer’s subjectivity is evidenced and reinforced by the professional associations that they are required to join in order to pursue their practice. A survey of the founding mission statement of any national association, such as the American Institute of Architects, the Royal Institute of British Architects, or the Lebanese Order of Engineers and Architects, reveals an overarching ambition to promote the status and power of the architectural profession within the given society. Which is to say, these professional associations are unequivocally not trade unions, and they never claim to help negotiate between workers and employers. They are, however and unfortunately, the only professional organisations that most architects and designers will join during their years of practice.

Throughout an architecture or design education and career, the individual is conditioned to identify with the totality of the professional designer class whose different strata are flattened into the figure of the steadily advancing designer. The designer may be currently precariously employed in the lower rungs of a firm whose grip on a sustainable inflow of commissions is tenuous, but she is surely to advance with the necessary investment of overtime, self-discipline, and self-initiated competition entries. She must therefore identify with her boss, and both must do their part to defend the value of the design profession. Solidarity is presumed to exist and flourish, if at all, on the grounds of shared profession. In this sense, over-identification with a professional class of designers coincides with the tendency for designers to see their work as a “calling,” and both cases end up dismissing the material realities of most design workers.

From there follows the grievance shared by many architects and designers that their role within the decision-making process is continually diminished and ceded to engineers, developers, clients, or state officials. So emerges the archetype of the embittered designer, in both private and public conversations. The Architecture Lobby argues that architects deserve a seat at the planning table if they are to more aptly negotiate in favour of the commons or a public good. While there is ample evidence to believe that an architect’s decisions will better champion the interests of a disenfranchised urban dweller than will the decisions of a developer, this still assumes a unanimous good will or a progressive politics in all design practice.

The argument of the imperiled profession and the mandate towards professional identification and self-defense rarely touch on questions of labour rights. Instead, they sweep under the rug the uphill struggles of more precarious design workers, let alone the struggles of workers operating in design-adjacent fields. Indeed, even when it is mobilised with attention to the hierarchies of labour within the profession, this argument still runs the risk of exceptionalising design work and reifying difference between design and other occupations. Instead, a further genericisation of our concept of design work may be helpful: beyond the creative genius of design and its idiosyncratic entrepreneurialism and towards an acceptance of its similarity to other kinds of contemporary labour.

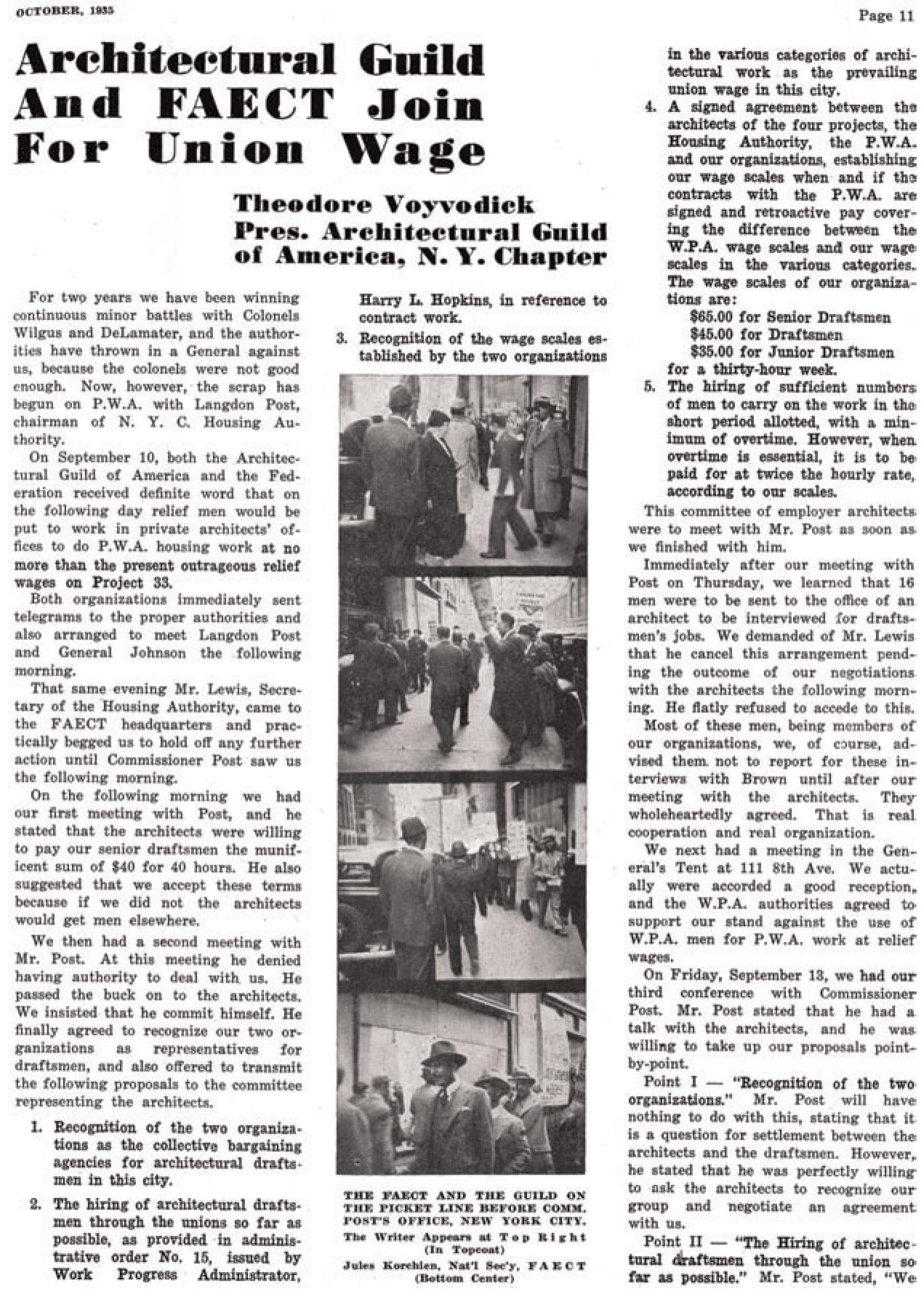

Newspaper clipping from 1935 about a picketing action by the Architectural Guild and the FAECT (Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians) in New York. FAECT was formed after members of the American Institute of Architects campaigned to turn it into a labor union and failed. FAECT was active between 1933 and 1948.

The Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists and Technicians (FAECT): The Politics and Social Practice of Labor by Mardges Bacon, Northeastern University.

In examining current notions of design labour, it’s useful to think about how designers actually employ technological tools, and how their role has developed with and against the reigning ideologies of the last decades.

Anyone who has been employed in a design or architecture firm knows well that the design process involves very little drawing and form-finding, and a lot of repetitive manipulation of variables, and translation of data into marketable spaces and systems. Proficiency in BIM and parametric software and fluency in a programming language have become essential requirements for designers entering the market. Rather than static forms gleaned from the mind’s eye, designers are increasingly expected to deliver dynamic and ostensibly intelligent assemblages: from adaptive websites to Generative Adversarial Neural Network-driven floor plans. This isn’t to say that relationships between capital and design have been fundamentally altered, but merely that information processing comes to bear in much greater intensity on the nature of work that designers perform. As cognitarians, to use Franco Berardi’s coinage, designers process and mould information, as well as their own passions, into artefacts and spaces that allow for the production of wealth and reproduction of life.

Additionally, these designed artefacts must repeatedly demonstrate that they are novel combinations of material, form, and structure. The pursuit of novelty comes to be punctuated with intellectual property laws, patents, and copyright claims, and designers do their part in the production of privatised knowledge. When thought in terms of novelty and intellectual property, design work seems not so dissimilar from the work that both artists and scientists perform. In Capital is Dead, McKenzie Wark calls this broad class of information workers the “hacker class,” foregrounding their role in manipulating repetition in order to create newness, regardless of whether any of the work involves direct handling of code.

Thinking through the characteristics of this class of workers, Wark questions whether there is common ground and struggle to be fought by both artist and scientist. The ability to engage in this shared struggle, however, is limited by the professional constraints placed on freedom of ideological belonging and expression. Even at the height of the Cold War, artists in the Western world could express explicitly anarchist or communist sympathies. Here we may recall Guy Debord of the Situationist International, who provided a great deal of intellectual inspiration for the Paris student protests of 1968, and had earlier expressed vociferous support and admiration for the Watts Riots of 1965 against racial segregation and police brutality. Conversely, scientists who espoused anti-capitalist views were largely silenced and coerced into performing an ethical neutrality, under the guise of scientific rationality and objectivity.

Suspended somewhere between the arts and the sciences, the design professions tended more towards science’s contrived neutrality, intervening in the Cold War’s ideological battles from behind a veneer of beauty and technical merit. It’s by no coincidence that in 1943, Ayn Rand chose an architect protagonist for The Fountainhead. Howard Roark came to embody the spirit of triumphalist individualism and design genius. Roark’s demonised arch-nemesis Ellsworth Toohey is a socialist architecture critic that Rand modelled after the real-world Harold Laski, who was a relatively well-known Marxist scholar and trade unionist. A real-world Howard Roark would be none other than Philip Johnson, inaugural recipient of the Pritzker prize, who went from being a Nazi sympathiser in the 1930s to shifting the curation at MoMA away from social housing and what he called “doing good” in the 1950s. At this time, mid-century design was being propped up by the U.S. State Department through cultural institutions and in international exhibitions to promote the splendour and largesse of the American capitalist’s lifestyle.

On the other side of the Iron Curtain, socialist design approached questions of manual labour and the working class, while continuing to impose hierarchies between different kinds of labour. A relevant example here is Gorazd Čelechovský’s Etarea, a design proposal for an automated ideal city of 135,000 inhabitants near Prague, submitted to the Montreal Expo in 1967. The city’s inhabitants would be scientific workers and intelligentsia who, liberated from the drudgeries of manual labour, could devote their time to intellectual advancement, socialist-humanist self-governance, and leisure. In his belief in the post-industrial intellectual worker as the revolutionary subject of the future, and in reliance on automation as a panacea for the problems of division of labour, Čelechovský resolved that Etarea could be classless because the classes of manual labourers simply did not live in Etarea. It could be less unequal only through more exclusion.

Interior perspective rendering of a bar in Etarea, frequented by members of the intelligentsia, with no service personnel in sight.

Čelechovský, G. 1967a. Etarea. Studie životního prostředí města [Etarea. A Study of Urban Living Environment]. Prague: Státní komise pro techniku & Pražský projektový ústav.

In the historical episodes above, the designer is a specialised expert separate from any conception of the working class, even within socialist design-currents that embraced the liberatory potential of automation. These questions relating to the automated city, design, and labour are handed down to us and they remain unresolved. As we sink deeper into the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a dire need to consider the role of design and automated platforms in allowing governments to re-open businesses and markets. Yet many contemporary design professionals and theorists seem indifferent to history’s lessons about design’s inability to escape the dominant ideologies of its time. They continue to preach the idea that novel design can break out of the political gridlock, that it can resolve our troubled relationship to the natural world in the Anthropocene.

In the thick of the initial wave of the pandemic, sociologist and design theorist Benjamin Bratton published the text “18 Lessons of Quarantine Urbanism” on the Strelka Mag platform. In the text, Bratton outlines a set of maxims around governance, platforms, and crisis response extracted from observing the way different state apparatuses responded to the outbreak. He issues a call to embrace the “artificiality” of our condition, staunchly arguing against the techno-pessimism that plagues a good deal of environmentalist and leftist reasoning. Among other observations, Bratton praises the role of automated platforms and delivery systems in allowing the exchange of goods to continue, while making no mention of the labour conditions endemic to said platforms such as Amazon.

Architect and researcher Godofredo Pereira subsequently criticised the text for its adoption of a narrowly technocratic position that does not account for several persisting material realities, not least of which is the devalued labour of human workers in sustaining the functioning of any currently-existing automated supply chain and service.

But Bratton’s position is emblematic of a wider branch of design theory that wishes not to alienate the tech industry, which is a strategic gamble that makes a lot of financial sense. While his opinions are not necessarily in the mainstream of the practising designer class described here, they represent technocratic design thinking taken to its logical endpoint. In his attempt at defending experts from encroaching populism, Bratton overreaches and his arguments dovetail with those of designers and architects invested in defending the interests of a professional class. An example of Bratton’s approach to the politics of emerging models and platform design is the following passage from a footnote in The Stack:

It will prove confusing to the left and the right that there is no necessary correspondence between planning an egalitarian economic system and a sustaining governance of the Anthropocenic ecology. We could have one without the other. With legacy state communism, we can have strong planning toward egalitarian economics that is also based on ecological devastation (such as Chavismo), and so it is possible that postcapitalist, postscarcity platform economics providing a “universal service level” may feature the stark absence of communitarian deliberation and consensus in any sense of vox populi mimesis. Comparing emergent systems to legacy systems (e.g., autocracy, anarchy, liberalism) may simply clarify less than it obscures.

Bratton pragmatically divorces sustainable ecological governance, communitarian deliberation, and a postscarce future from one another. His argument is, first, that ideological shortsightedness on the left has led to the belief that egalitarian social relations are a prerequisite for sustainable governance in the face of climate change. And, second, that this belief is a hindrance to a scientifically sound approach to planning and design. Meanwhile, he collapses the left into actually-existing “legacy” state communism, legacy being a term repurposed from software studies meant to denote an outdated version of a program. This is one among many instances where Bratton extrapolates terms from within software and design studies onto the wider world, taking them well beyond the limits of the designed object or system that they are derived from. It’s also difficult to make out exactly what intention lies in reducing communitarian deliberation to a “mimesis” of vox populi. Ultimately, are “emergent systems” really so complex as to preclude any traditional analysis of the pre-existing powers that undergird and are upheld by them? Is there no presentism whatsoever in assuming that our contemporary technological systems have outmoded centuries-old political and economic categories? Why propose that a “universal service level,” meaning a minimum of welfare provision and perhaps a basic income, is either possible or desirable without massive redistribution and collective ownership and decision-making?

Technocracy is and always will be a pretend non-ideology ideology. Try as it might, it cannot break out of the political spectrum. At best, it is a kind of centrism that believes it can cater to interest groups and populations with divergent political beliefs through technological efficiency: all it needs is the perfect collaboration between states, private sector, and experts. For both Bratton and Čelechovský, it is implicitly assumed that a rule of experts can replace the need to consult with the manually-labouring population at large. Čelechovský believes that his designed city will be a near-utopian ideal because no manual workers will dwell in it, while Bratton assumes that future decision-making about welfare and climate change might not require any input from the populations directly affected by those decisions.

It’s one thing to defend scientific and technical insight from sweeping anti-expert opinions in partisan rhetoric, and another thing entirely to interpret the consequences of neoliberal governmental policy and of racial capitalism as failings of design that can be righted with more expertise. Yet designers, technologists, and other professionals constantly reproduce this logic at different scales. While they may do so in the genuine belief that design genius can resolve problems of governance, either way, they are liable to advance an implicit defence of the interests of the expert class, running against the struggles being fought to dismantle the same structures that this class is a part of.

A protest by undocumented migrant workers at the construction site of the French newspaper Le Monde’s headquarters, designed by Snøhetta in February 2020. The Funambulist released a letter addressed to Snøhetta demanding action on the architecture firm’s part.

The Funambulist.

But if designers do finally reject the assumption that their practice can operate independently of its socio-economic base, what are they to do? Do they not relinquish agency when they admit that the most pressing problems are not design problems? On the contrary. Breaking out of the impasse is not a rejection of expertise or of technological advancement, but a rejection of a rule of experts. There is more work to be done at present to craft a consciousness of design labour that both refuses feigned colour-blind technocratic neutrality and escapes the binds of narrow professional identification. This consciousness would also have to take stock of the material conditions of labour that design and architecture cultures propagate.

Identifying as design workers and operating as such should not create false equivalences with workers in design-adjacent industries and elsewhere, such as construction workers and the service staff in their offices. Their professional duties, struggles, and lifeworlds are vastly divergent, as has been evidenced by the pandemic, where some have been able to retreat to the safety of their homes as others have faced vastly higher risk of infection and further reduced access to social safety nets. Yet this is precisely why there is a lot more political agency to be exercised in cross-professional action and organising. If it cannot be expected of designers at the top of the value chain to work against their own economic interests, then they must be pressured to do so by those whose interests are indeed at stake. The least we can do presently is write more open letters and form unions for design workers in rejection of their conditions and the conditions of those in their proximity. In the architecture field, this work is already being done by alternative associations such as the Architecture Lobby, and UVW’s Section of Architectural Workers.

More broadly, the “hacker class” which includes precarious architects, designers, technologists, and artists, must develop a greater awareness of itself and find ways of building alliances with other dominated classes. This also means reckoning with interest groups that are outside of the labour movement, such as tenants’ unions, debtors’ unions, and anti-prison groups, in recognition of the fact that full employment has always been and will continue to be impossible. This truth must come to bear on what forms of organising are deemed more or less legitimate and given due attention.

The great majority of us are required by necessity to continue to take on alienated design work, both as employees and enterprising freelancers. Which is why what is here being referred to as a betrayal is not a forsaking of the profession and of design labour in general, but is a call to surpass association and political action based solely on shared profession. Both the latent ideologies and current labour conditions inherent to design thinking and practice are better off closely examined, negotiated, and/or refused. This is because the expanded socioeconomic processes that design work is part of not only imbricate other kinds of workers but ultimately also govern non-working populations deemed surplus and disposable by state and capital. To put it bluntly, the design solution will always be to reform, rethink, restructure, optimise, or streamline a prison system, but never to demand its abolition. In the words of Ruth Wilson Gilmore, the work to be done against organised abandonment—and that necessarily includes design work— must not only be green, as in ecological, but also red, as in communised.