This article is part of the FA special series Building Workers Unite

The period known in Portugal as the “Ongoing Revolutionary Process“ (25th April 1974- 25th November 1975) brought unprecedented visibility to the country’s underprivileged classes. Emerging in response to a military coup d’état, the people’s class consciousness was taken to the streets, with mass movements expressing a renewed awareness of their fundamental right to healthcare, food, education and quality housing. In order to support this grassroots political awareness, unveiled by the revolutionary event, public policies were put in place by the transitional government to meet the people’s demands.

Up until that point, large sections of the Portuguese population experienced dreadful housing conditions. Under the umbrella of a paternalistic dictatorship, exploitative labour conditions and strong pressure exerted by a privately-controlled housing market combined to force a substantial number of families to sub-lease meagre accommodation, live in ilhas (literally, ‘islands’: precarious units of collective housing built in the interior of urban blocks by the owners of the plots in order to increase rent extraction) or find residence in extremely dense communities of illegal shacks. Meanwhile, where the government did intervene, the policy was to relocate poor communities into newly developed areas on the urban periphery.

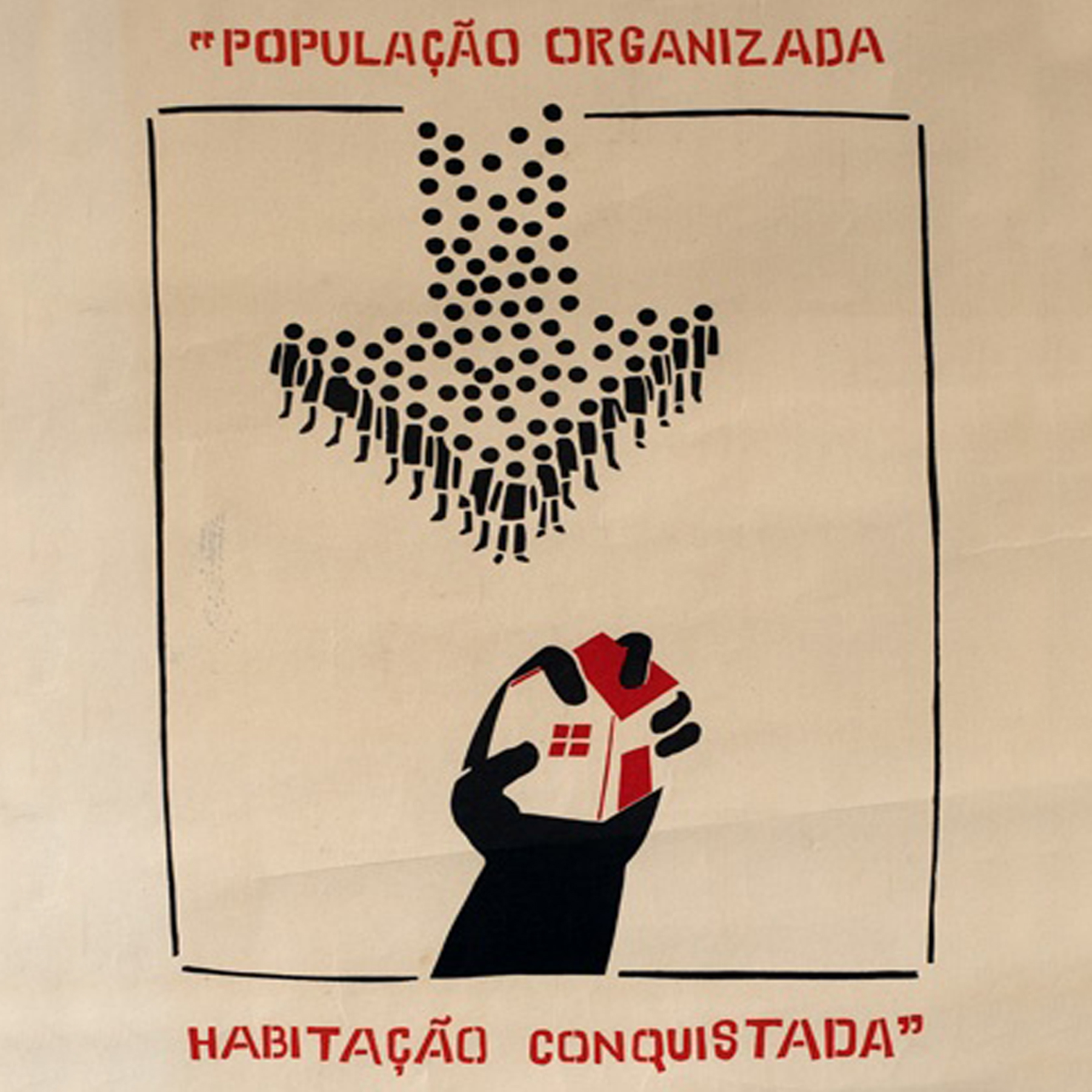

Under the revolutionary process, however, local communities were allowed to organize their demands in neighbourhood associations and housing co-ops, whose purpose was to reclaim decent accommodation financed by the state within the neighborhoods they had called home for many years.

Decreed by then State Secretary for Housing and Urbanism, architect Nuno Portas, the SAAL (‘Serviço Ambulatório de Apoio Local’; translated as Mobile Local Support Service) aimed to provide these sections of the population with the means to design and build their own houses and communities. In order to meet this provision, the state became not only responsible for subsidizing the operations (in some cases, through non-repayable funds), but also for soliciting and remunerating so-called “technical brigades” composed of both architects and architectural students. These technical brigades would provide the requisite technical (and artistic) assistance to those communities.

This situation of dual power, wherein people on the streets were temporarily able to exercise power over and above the government, opened the window for an unprecedented democratic way of conceptualising and building the city. As far as citizens were concerned, it offered them a chance to escape the ruthless imposition of real estate, and to express their particular visions and ideas of a dignified city. For young architects, it gave them new opportunities to experiment on an urban scale. They were also able to restructure their social role, which had hitherto been trapped between the bourgeois affectations of the liberal architect and the technical bureaucracy that came with working for a centralized state apparatus. Last, but not least, for students the situation represented the possibility for a ‘radical pedagogy’, as Joaquim Moreno puts it. It allowed them to overcome the limitations of the school and learn to build within a context where reality and ideology, political activity and disciplinary knowledge, objectivity and subjectivity, were refined dialectically. For that period, rather than being an institution of redundant protocols and canons, architecture became the universal right to a self-determined and dignified organization of space: a rich and multi-layered experience of concrete and collective expression, both on a disciplinary and political level.

With all that said, this process was only possible under specific historical circumstances. The revolution had temporarily brought capitalistic dynamics to a halt and reset the country on a path to socialism. On one hand, large sections of the population were mobilized to unveil and denounce social contradictions. On the other hand, invested political agents, like Portas, proved to be agile enough to unlock the bureaucratic apparatus of the State, and direct it to the benefit of the people. However, after a counterrevolutionary turn, the legal ‘normality’ of the bourgeois state was gradually reinstated and the SAAL operations ceased by decree on 26th October 1976, eventually opening the door to a new housing regime driven by state subsidised financial credit.

This was the way the wind was blowing in the late seventies. After decades of global emancipatory political struggles, the world started to experience a ‘neoliberal turn’. Omnipresent free markets synchronized time and space all over the world. Labour became global, flexible, and mobile. The realms of extraction (e.g mining) and production (e.g. factory work) were systematically exported to poorer corners of the planet. Meanwhile, the governments of developed countries gradually allowed markets to expand once more into housing and the reproductive sphere (characterised by work that nurtures and regenerates the workforce and activity that re-creates the existing economy). If in the previous framework of welfare states, production and reproduction were co-dependent and regulated to varying degrees by the state, in this new phase of economic development full privatization became the order of the day. Housing went from a fundamental right to a stable and safe investment, for both domestic and foreign finance.

In Portugal, this paradigm had become fully entrenched by 2012, the year in which a right-wing government, controlled by the so-called European ‘Troika’ (composed of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund) implemented austerity measures which included the liberalization of the rental market. In a sunny, quiet and inexpensive country, cursed by the sense of opportunity of big corporations such as Ryanair or Airbnb, this was a perfect recipe for profitable tourist-oriented urbanity, monopolized by private investment.

Some of the most recent statistics are essential to understand the scope of these policies. Take Porto for instance. Here, government had made considerable public investments in the city’s public and transport infrastructure under the pretext of becoming European Capital of Culture in 2001. The resulting boost this gave to the local tourist trade, in turn, had the effect of increasing the potential land rent. Now, some neighbourhoods have become more than 50% tourist accommodation, with 57% of the houses in the city center requiring the eviction of long-standing residents against their will. For an 80 m2 one-bedroom apartment, the average price is as much as €600 (precisely equivalent to the National Minimum Wage). Even the percentage of public housing owned by the municipality widely superior to the national average (13% against 2%) is insufficient to counteract this tendency. As growing sectors of the population, young and old, are deprived of a home of their own, the housing crisis has become as big a threat as low wages and unemployment.

On the flip side, the labour of those who plan and build the city has become a battlefield between productivity, profit and austerity. At the core of this dynamic, architects stand in a privileged position to understand the systemic nature of precarity. As it goes, not only is their labour exploited, but they are forced to act as agents of other people’s exploitation. In fact, a quick overview of any given Portuguese studio’s most recent output frequently reveals their active participation in the gentrification process, wherein they use their disciplinary background to prettify this dispossession: increasing the exchange-value of those houses, often through the application of materials produced on the other side of the world under substantially worse labour conditions.

For architects, as with most workers, this culture of exploitation cannot be understood without reference to the new rationale that has come to dominate the world’s political economy since the 1970s. As Byung-Chul Han brightly illustrates in his book Psychopolitics, today’s capitalism preserves its power by seducing the mind. It encourages citizens to feel a sense of opportunities waiting to be seized and an all-encompassing ambition to succeed and satisfy their own desires. Workers become entrepreneurs-of-the-self, in charge of every aspect of life-as-investment. In the architectural realm, this means regarding a career choice in which you have subjected yourself to exploitative work conditions as a potential gain if you eventually succeed your masters.

Both dependent on and unable to escape the dominant structures of private initiative, if not lucky enough to have access to commissions of their own, young architects face a dangerous deadlock: either (1) alienate themselves in a big architecture office, with conspicuous connections to the real estate industry, and subject themselves to an abstract hierarchy of decisions; (2) find a smaller office presumably with good intentions, but running on overtime and underpaid labour; or (3) throw themselves at the mercy of the market as a start-up, whose specific disciplinary knowledge merges with those of management and marketing, and whose time is mostly spent promoting their image in social networks (as seems to be the case with a studio like fala atelier).

As Guy Debord puts it in La societé du spectacle, it is clear that “the “success of an economic system founded on separation inevitably leads to the proletarianization of the world.” In the realm of architectural labour, this is clearly crystallized in the division between those who plan, those who build and those who will live in. A split which transformed buildings into commodities, architects into entrepreneurs and disciplinary knowledge into a source of surplus-value. A separation which, as tested within the SAAL, must be abolished in order to reverse this proletarianisation of both ‘producers’ and ‘consumers’.

While we may be far away from the historical circumstances which produced the Portuguese Revolution, it is both possible and urgent to restate the housing question. Still today, after 40 years of democratic communist administration, the Spanish town of Marinaleda offers the land, materials, and technical support of municipal architects to those who want to build their own house, with the only conditions being that the beneficiaries participate in the construction process and cannot sell the house in the future.

In Portugal, meanwhile, something else has been inherited from the revolutionary period: it was written in the constitution that “everyone has the right, for one and the respective family, to an adequate and properly dimensioned house, with both hygienic and comfortable conditions, allowing oneself personal and familial intimacy”. In the same constitutional article, it is written that it is the state’s duty to promote and offer conditions for communities to organize themselves in order to solve not only their housing needs, but also the social equipment required for living-together.

Even so, last year, a governmental survey on the existing housing needs showed that 25,762 families lived in “clearly unsatisfactory conditions” and 31,526 homes lacked the “minimal habitability conditions”. If, on top of that, you consider the amount of work required to adjust the overall built environment to the severe climate transformations already being experienced across the world, it is not hard to recognize the inevitable collective dimension needed for the effective realisation of these efforts, as well as the sheer limitations of private property and our current economic model in general.

Today’s capitalism reproduces its dominance through an individualist and market-oriented ideology which assumes that everything should be run as a business. Therefore, to invert the rule of real estate and private initiative, we ought to invent new ways of organizing space sustained by values other than productivity, marketability and profitability. In practice, this means that we need to envision a system where people own the means of production of their own time and space; and under which the architects’ knowledge and labour are matters of the common. To do so, we could even take inspiration from already existing structures, such as the policy common to many countries of providing free legal representation to every citizen.

In 2015, 40 years since the Revolution, Portugal’s Socialist Party formed a minority government which was supported by an alliance of Ecology Party “The Greens”, Left Bloc and the Communist Party. Thanks to this unprecedented left-wing alliance, as well as the long-standing commitment of people like architect-politician Helena Roseta, a National Fundamental Law of Housing was approved by the Portuguese parliament in July 2019, creating the political and legislative tools to address this housing crisis.

Interestingly, it is within this context that Portuguese architects formed the Architectural Workers’ Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores em Arquitetura — MTA). Established in the latter half of 2019, the organisation has vowed to mobilise architectural workers to struggle collectively against the increasing precariousness of their work. However, while their manifesto represents a legitimate will to regulate and improve the specific material conditions of wage and salaried workers in architecture, it also reveals a missed opportunity to question the wider implications of this neoliberal mode of producing space, as well as the urgency to establish new social and political horizons for the profession.

This is why the early disruption of the SAAL process is still so important. Precisely for being unfinished, lessons remain to be learned from this moment, when architects worked for and with the people to solve their housing needs. As citizens, strengthened as a professional class, architects should channel their efforts into pushing for the materialization of these rights, while claiming their own emancipation from private rule. As the MTA implies, architects must unite and organize, yes; but as with the earlier precedent set by SAAL they must do so for and with the people that they themselves belong to, rather than lobbying exclusively for their own professional interests. If done well, this ambitious struggle could act as a trigger to reawaken the class consciousness that both architects and citizens have lost in the post-revolutionary period. After all, what’s better: working a precarious and alienated internship, or joining a renewed incarnation of the technical brigades, working directly with your local community?